Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6410

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 1

Department of Neurology, Hospital Municipal Doutor José de Carvalho Florence, Brazil

Correspondence: Richard Mady Nunes, Department of Neurology, Hospital Municipal Doutor José de Carvalho Florence, Brazil

Received: May 22, 2017 | Published: June 19, 2017

Citation: Nunes RM, João RB, Motta ACBS, Azevedo RV, Mussi ML et al. (2017) An Atypical Presentation of Spinal Epidural Hematoma-Case Report and Literature Review. J Neurol Stroke 7(1): 00227. DOI: 10.15406/jnsk.2017.07.00227

Spinal epidural hematoma can occur spontaneously or as a secondary condition and it represents less than 1% of space-occupying lesions within the spinal canal. The incidence of spontaneous epidural bleeding is estimated to be 0.1 cases per 100,000 populations per year. Typical clinical manifestations include acute onset of back pain, sometimes associated with radicular paresthesia and signs of spinal cord compression in some cases. The clinical presentation with hemiparesis is rare, and it may hinder the diagnosis, especially in emergency situations. The purpose of this article is to present a clinical case of acute epidural hematoma with atypical clinical presentation, followed by literature review of spinal epidural hematoma.

Keywords:spinal epidural hematoma, spinal cord, hemiparesis, stroke, intravenous thrombolysis

Spinal epidural hematoma (SEH) is a rare neurological condition with challenging clinical management,1 especially in emergency situations in which there are misleading atypical features that simulate other more common diagnoses,2 In this article, we describe a case of SEH diagnosed in our emergency department presenting with atypical history and findings. This report will be followed by discussion and review of the relevant medical literature.

A 71-year-old male patient with a history of obesity, hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to our emergency department after experiencing sudden onset of moderately intensity interscapular pain of short duration at home, while walking. He subsequently rapidly progressed with right side hemiparesis within the next 10 minutes from the initial symptoms. He was brought to the emergency department of Municipal Hospital Dr. José de Carvalho Florence. At time of arrival there was no report of pain. His current medications were: AAS 100 mg/day and Losartan 50mg/day. Forty five minutes from the onset of neurologic deficit, the patient was evaluated for possible thrombolysis therapy according to standard protocol criteria.

At admission his vital signs were stable and no other non-neurologic abnormalities were found on his physical examination. His hemiparesis remained unchanged. The neurological examination data was as follows: complete right sensory-motor hemiparesis (facial assimetry, muscle strength grade III in proximal and grade 0 in distal right upper limb, grade 0 in right lower limb); hypoactive tendon reflexes in left upper limb and abolished in the other limbs; absent Hoffmann sign bilaterally, flexion response in left plantar reflex and indifferent response in right plantar reflex. Ancillary laboratory tests (INR, platelet count), imaging (Computed Tomography of the Head, chest radiograph) and EKG were all reported within normal.

Considering the ictal pattern of presentation as well as the physical examination and results of complementary tests, thrombolysis treatment was offered with a provisional diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. At presentation, his stroke scale was graded 8 by NIHSS (National Institute of Health Stroke Scale) and he met the inclusion criteria without exclusion criteria. After obtaining verbal and written consent, one hour and forty-five minutes from the onset of symptoms, intravenous thrombolytic therapy was initiated and he was given Alteplase (total dose of 81mg).

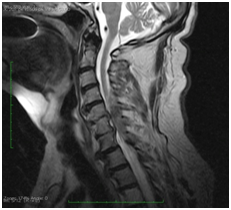

After the thrombolytic therapy, his NIHSS was noted to be 7 and there was evidence of partial recovery of strength in the right upper extremity. At the same time, he reported new interscapular pain radiating to the cervical region. Considering the persistence of pain, despite the mild but gradual neurologic improvement, magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical and thoracic spine was obtained. MRI revealed a posterior epidural intraspinal lesion extending from C4 through C7, along the dorsolateral aspect of the spinal canal and toward the right side, compatible with diagnosis of SEH (Figures 1-4). Decompressive laminectomy was then performed resulting in progressive recovery of the neurologic deficits (strength grade IV in both right upper and lower limb in the outpatient follow up).

Figure 1 Sagittal T2 weighted image MR through cervical spine shows a heterogeneously hypointense dorsal epidural lentiform shaped lesion, between C4 to C7 levels causing cord compression and edema.

Figure 2 Sagittal T2 weighted image MR through cervical spine shows a heterogeneously hypointense dorsal epidural lentiform shaped lesion, between C4 to C7 levels causing cord compression.

First described in 1869 as spinal apoplexia 3, Spinal Epidural Hematoma (SEH) is a rare neurological condition with a frequency accounting for less than 1% of spinal epidural space-occupying lesions.1 This condition can be secondary or spontaneous. The incidence of spontaneous SEH (SSEH) was estimated at 0.1 cases per 100,000 habitants/year.4,5 It’s typical clinical presentation involves local pain of acute onset unrelated to trauma or physical effort, sometimes associated with radicular paresthesias and with subsequent evolution to spinal cord compression,1 usually manifesting as tetraparesis, paraparesis or Brown-Séquard syndrome.6,7

In general, transient hemiparesis is a very rare presentation of SSEH.6,8 However, this clinical manifestation is relatively more frequent in specific epidural hematomas of the cervical portion. As suggested by a recent systematic review of 50 cases of cervical SEH, hemiparesis occurred in 24%. In the same group of patients, imaging studies reported a predominance of injuries located from C4 through C7 levels on sagittal plane and more frequent dorsolateral impairment of the spinal canal on the axial section. This study concluded that the mass effect in the dorsolateral lower cervical portions contributes to the unilateral compression of the spinal cord.9

Groen et al.,10 suggested that the involvement of the posterior internal vertebral venous plexus has an important correlation with the onset of SEH. It is believed that such anatomical structure is more vulnerable to venous pressure variations by the absence of valves in their vessels.10 The fact that cervical involvement frequently occurs in the lower portion is due to the structural arrangement of the thecal sac between C5 to C7 (this segment is more susceptible to changes in its conformation by flexion and extension of the column).11

When considering the relationship between age and specific involvement of spinal portions, studies suggest that, in patients aged up to 40 years old, the cervical portion tends to be the most affected, while in elderly patients the occurrence is more frequent in the lumbar portion.3,10

In medical literature we have found some cases of lateralized motor or sensory-motor deficits initially attributed to a stroke which was actually caused by SEH. In those cases, the management and therapy was variable according to details of clinical presentation.

In 2008, D 'Souza et al.,12 described the case of a 68-year-old patient with a sudden onset of pain in his shoulder and sensory-motor deficit on the right hemibody that was presented with facial asymmetry on the same side (mistakenly considered facial hemiparesis) and 6 score in NIHSS. The intravenous thrombolysis considered at first was excluded after clinical evaluation demonstrated the possibility of SHE.12

Another case report has shown the case of a 69-years-old patient who presented cervical pain and a pure motor deficit in right upper limb and right lower limb who was erroneously submitted to anticoagulation therapy.13 Two other authors and their collaborators have described similar situations.6,14

The radiological investigation with a spinal cord CT may be useful in emergency evaluations due to the ease of access and speed in obtaining results; however, a case has been reported in which CT failed to show the hematoma.15 Compared to CT, MRI is the modality of choice with significant higher sensitivity for evaluation of spinal contents and spinal pathology, given its better capacity for tissue characterization.2

Treatment of SEH with cord compression and neurological deficit requires emergency surgical intervention with decompressive laminectomy. The prognostic factor is directly related to the time between the onset of symptoms and the decompression of the hematoma. Groen et al. 10 have shown better outcome of surgically addressed patients within 48 hours (cases of incomplete spinal cord dysfunction) and within 36 hours (cases of complete spinal cord dysfunction) of the onset.10

We reported a case of difficult diagnosis of SEH due to its atypical presentation of right upper and lower limbs hemiparesis associated with facial asymmetry, both considered as stroke mimic factors. Moreover, the short episode of acute upper back pain preceding the neurologic deficit was not a complaining at the time of admission, probably leading to erroneous diagnosis. The thrombolytic treatment might have caused additional bleeding and the new onset of interscapular pain, now leading to a correct suspected diagnosis of intraspinal epidural bleeding, then confirmed with dedicated spinal MRI.

Both the early recognition of SEH as a possible complication of intravenous thrombolysis and the surgical intervention are contributing factors to the eventual functional recovery and good outcome in cases similar to this.

None.

None.

None.

©2017 Nunes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.