Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6410

Case Report Volume 10 Issue 1

Department of Internal Medicine, Serviço de Saúde da Região Autónoma da Madeira, Funchal, Portugal

Correspondence: Rafael Ferreira Nascimento, Department of Internal Medicine, Serviço de Saúde da Região Autónoma da Madeira, Funchal, Portugal, Tel +351912153471,

Received: January 28, 2020 | Published: February 12, 2020

Citation: Nascimento RF, André DR, Freitas JM, et al. A subtle stroke. J Neurol Stroke. 2020;10(1):50-51. DOI: 10.15406/jnsk.2020.10.00409

Introduction: The authors present a clinical case of an ischemic stroke that presented with anomic aphasia.

Case report: A 75-year old woman was brought to the emergency department with an anomic aphasia that had started that day. The neurological exam confirmed the anomic aphasia with no other associated findings. The Head-CT Scan showed focal points of ischemic gliosis without any other acute changes that could suggest vascular lesions particularly in the middle cerebral artery territory. The patient was hospitalized in the cerebrovascular disease unit with the diagnosis of ischemic stroke. During her stay at the unit, the patient developed a decreased nasolabial fold prominence on the right side, motor aphasia, dysmetria and a lack of balance while walking. On the fourth day, the patient underwent an MRI that revealed a sub-acute infarction in a partial territory of the left middle cerebral artery with a partially re-canalized thrombus in the inferior M2 branch of this artery. Blood work showed a dyslipidemia. The echocardiogram detected a type 1 diastolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 55%. Patient was discharged after 8 days. Currently, the patient is followed in the cerebrovascular diseases department. The neurological evaluation demonstrates aphasia with some impairment of comprehension and naming, the speech has fluency loss showing occasional anomic pauses and paraphasias.

Conclusion: The authors alert to the fact that a stroke can present itself in multiple ways, stressing the role of the clinical symptoms in its diagnosis.

When a patient presents himself with changes in verbal expression or understanding the people around him, we usually frame it in the field of the aphasias. Aphasia is frequent in the acute and sub-acute stroke accounting for 1/3 of presentations.1 According to studies published to date the frequency of aphasia is located between 21% - 38%.2–10 The remission of aphasia occurs mainly in the first 3 months, but little is known about the recovery course within these 3 months.6,10,11 The article shows a case of an anomic aphasia due to an ischemic stroke and the subsequent recovery of the patient.

A 75-year old woman with known hypertension was brought to the emergency department with an anomic aphasia with three and a half hours of evolution. The neurological exam confirmed the anomic aphasia with no other associated findings. Her Head Computed Tomography (Head-CT) Scan showed focal points of ischemic gliosis without any other acute changes, namely density or morphology of brain tissue, that could suggest vascular lesions particularly in the middle cerebral artery territory (Figure 1) showing a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 3.

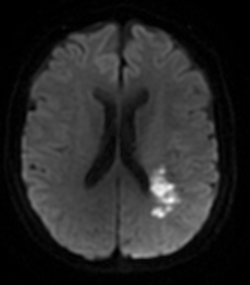

The patient was hospitalized in the cerebrovascular disease unit (CDU) with the diagnosis of ischemic stroke. During her fourth day at the unit, the patient developed a decreased nasolabial fold prominence on the rigth side, motor aphasia, dysmetria and a lack of balance while walking, the patient underwent a Magnetic Ressonance Imaging (MRI) scan that revealed a sub-acute infarction in a partial territory of the left middle cerebral artery with a partially re-canalized thrombus in the inferior M2 branch of this artery and signs of light to moderate ischemic leukoencephalopathy (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Sub-acute infarction in a partial territory of the left middle cerebral artery with a partially re-canalized thrombus in the inferior M2 branch.

Blood work showed a total cholesterol level of 230 mg/dL, LDL of 170 mg/dL and triglycerides of 96 mg/dL with no other significant alterations. The patient was in sinus rhythm with 80 beats per minute, the transthoracic echocardiogram detected a type 1 diastolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 55%. Patient was discharged after 8 days with a NIHSS score of 2. The eco-doppler to the neck vases shows no significant changes according to age and gender.

Currently, the patient is followed in the cerebrovascular diseases department presenting herself conscious, oriented in space and time without lateralized deficits, although she maintains the aphasia with some impairment of comprehension and nomination. Her speech has fluency loss showing occasional anomic pauses and paraphasias. She also shows a spacial, construtive and ideomotor apraxia associated to an apraxic march with need of supervision on the daily life activities.

The author’s presents a clinical case of aphasia due to an ischemic stroke, what is quite peculiar in this case is that the only change at the neurological exam was the presence of an anomic aphasia without any other deficits. Even though the patient had only history of hypertension, this precedent is one of the three most common risk factor for stroke alongside diabetes and atrial fibrillation.12–14 Clinical manifestations evolve rapidly during the first hours after the stroke [16] this is particularly true for aphasia.15 As we can see during her stay at the CDU the patient developed signs of an ischemic stroke in progression such as decreased nasolabial fold prominence on the right side, motor aphasia, dysmetria and a lack of balance while walking. In this situation in spite of a NIHSS score of 3, the vigilance was tight in order to take invasive measures if the patient needed so but that was not the case. Studies show that aphasia outcomes remain poor: 32% to 50% of aphasics still suffer from aphasia 6 months after stroke.5,6 When the patient started being followed in an out-of-the-hospital regimen she displayed at first aphasia with some impairment of comprehension and nomination, a speech with fluency loss showing anomic pauses and paraphasias and a spacial, construtive and ideomotor apraxia associated to an apraxic march, taking this into account she started speech and physiotherapy. One month and a half after the discharge from de CDU the speech had become fluent but the patient maintained a low degree of apraxia, showing a balance and gait impairment with an unstable heel to toe walk. Finally, after three months and a half of speech and physiotherapy the patient showed no functional restrictions and no speech impairment, showing a favorable recovery in the time since discharge from the CDU. This article goes to show that the clinical case of an aphasia may be subtle as it was shown but if treated and oriented well, the sequels can be reduced to a minimum.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

©2020 Nascimento, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.