Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6410

Case Report Volume 10 Issue 3

1Department of Neurology, Cukurova University School of Medicne, Turkey

2Department of Pathology, Cukurova University School of Medicine, Turkey

Correspondence: Filiz Koc, MD, Department of Neurology, Cukurova University School of Medicne, Turkey

Received: April 29, 2020 | Published: June 4, 2020

Citation: Demir T, Koc F, Erdo?an S. A case of pseudotumor cerebri secondary to acute leukemia. J Neurol Stroke. 2020;10(3):105-107. DOI: 10.15406/jnsk.2020.10.00420

Introduction: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a rare clinical condition in which an increase in intracranial pressure is seen without a lesion in the head. The association of IIH with haematological malignencies is not well known.

Case: We present 19-year-old male with frequent episodes of headache that lasted up to 24 hours, localized to the bilateral temporal region accompanied with nausea and vomiting for two months. On the neurological exam, the lateral gaze was slightly restricted. Ophthalmological exam revealed bilateral papilledema, which was more pronounced on the right. Bilateral concentric constriction, more pronounced on the right , was observed on the computerized visual field exam. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed swelling in the optic nerve sheats, rather than on the right. In the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the opening pressure was 370 mmH2 Cytological examination of the CSF showed atypical lymphoid cells. The patient was diagnosed as precursor lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma.

Conclusion: Acute leukemia–induced clinical IIH has not been reported in the literature up to now, and the present case study will contribute to the literature in this regard. This phenomenon will be noteworthy for clinicians who encounter high CSF opening pressure, abnormal CSF biochemistry, and substantial cytology in cases presenting with clinical IIH.

Keywords: pseudotumor cerebri, acute leukemia, haematological malignancy, intracranial hypertension, headache

Pseudotumor Cerebri (PTC) is a rare clinical condition in which an increase in intracranial pressure is seen without a lesion in the head. The incidence of the disease varies between 0.03-2.36/100.000, although it is more common in obese women in the age of fertility, and can be seen in every age and sex.1 The pathogenesis of the disease is not clerly known yet. The most common clinical presentation is headache, and blurred vision, decreased visual acuity, visual field defects, double vision may be seen as the complaints of the patient. In the aetiology, drugs such as corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, minocycline, tetracycline, sulfasalazine, vasculitis such as Behcet’s Disease and systemic lupus erythematosis, arteriovenous malformations, sleep disturbations, extracranial venous hypertension secondary to cardiac septal defect, uremia, iron deficiency anemia, menstrual irregularities, hypo and hyperthyroidism.2–16 The association of PTC with haematological malignencies is not well known. In this article, we report a case of PTC secondary to acute leukemia.

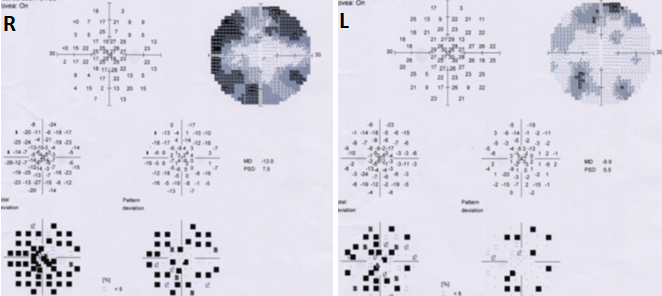

A 19-year-old male patient admitted to outpatient clinic due to the frequent episodes of headache that lasted up to 24 hours, accompanied by nausea and vomitting, localized to the bilateral temporal region. The hedache is pulsatile and showed partial response to analgesic drugs. Six months ago he was diagnosed with Rheumatoid artritis (RA) and hypotyridism because of the complaint of joint pain. The patient started to take methotrexate and prednisolone but he had stopped using these medicines voluntarily for the last 2 months. The family history was not remarkable. On the neurological exam, the lateral gaze was slightly restricted. Opthalmological exam was revealed bilateral papilledema, more pronounced on the right. Visual acuity was normal in the both eyes. The other system exams were normal. His hemoglobin concentration was 13.1 gr/dL,and his white blood cell (WBC) and platelet count were 11.28X103 and 223X103, respectively. Biochemical panel containing fasting blood glucose, bloon urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, aspartate transaminase (AST, alanin transaminase (ALT), sodium, potassium, calcium, vitamin B12, and folat was normal. Thyroid function tests (free T4: 0.53, Tiroid stimulating hormone (TSH): 4.28 ), thyroglobulin, antimicrosomal and antithyroglobulin antibodies were within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (44 hours) and C-reactive protein (11.6 mg/dL) were higher. Electrocardiogram revealed normal sinüs rhytm, and chest radiograph and full urine examination were normal. Antinucleer antibody (++); anti dsDNA, anti SS-A, anti SS-B, c-ANCA and p-ANCA were negative. Bilateral concentric constriction, more pronounced on the right , was observed on the computerized visual field exam (Figure 1). Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed swelling in the optic nerve sheats, rather than on the right, (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Computerized visual field exam showed bilateral concentric constriction, especially on the right.

In the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) the opening pressure was 370 mmH2O, CSF protein and electrolyte levels were witin normal limits, and there was not pleocytosis, serology and culture were negative. The patient had started to take acetozolamide 750 mg/d and dexametazone 12 mg/d. In the 7th day of treatment the opening pressure of CSF was measured as 290 mmH2O. Cytologic exam of CSF showed atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). In bone marrow biopsy, atypical lymphoid cells were diffuzely stained with Pax 5 by immunohistochemical method (Figure 4). The patient was diagnosed as precursor lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. The patient who transferred to the Hematology clinic died on the 26th day of admission because of the sepsis on 20th day of admission.

Although PTC is defined as a benign condition with many risk factors, it is the disease that can cause disability due to its complication such as blindness. The presence of high openning pressure of CSF confirmed the diagnosis of PTC. We think that although the patient has the risk factors of PTC such as RA, hypothyroidism and corticosteroid use, joint pain may be the bone pain, and he was misdiagnosed . He was not on medication for RA fort he last 2 months. We also did not find any evidence in literatüre that the prednisolone and methotrexate used by the patient may cause PTC. Fort his reason, it is difficult to say that these drugs cause the disease. During the diagnosis, thyroid function tests were normal and there was no evidence of endocrinopathy such as Hashimoto Thyroiditis.

It should also be kept in mind that POEMS syndrome characterized by polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy and skin changes is paraneoplastic syndrome. POEMS was excluded because the patient did not have polyneuropathy findings, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes. Castleman disease, a lymphoproliverative disease, should not be overlooked in differential dignosis. However the lack of lympadenopathy enabled us to exclude Castleman disease.

Until now, there are no data showing that there is a direct relationship between haematological malignancy and PTC in the literatüre, but there are reports of acute promyelocytic leukemia with PTC development during treatment with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)(17-19).

In this case, the presence of systemic and methabolic disease that could play a role in aetiology of PTC was investigated in detail by labratory methods, venography and protrombotic conditions were evaluated in terms of possible sinüs vein thrombosis.

The acute leukemia induced PTC clinic has not been reported in the literatüre up to now and will contribute to the literatüre in this regard. This phenomenon will be noteworthy for clinicians who have shown that CSF oppening pressure, biochemistry of CSF as well as cytology is substantial in cases presenting with PTC clinic.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2020 Demir, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.