Journal of

eISSN: 2373-437X

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 4

1Department of Microbiology, The Libyan Academy, Libya

2Department of Botany, Benghazi University, Libya

3Department of Dermatology, Jumhuria Hospital, Libya

Correspondence: Warda Mohammed Bridan, Department of Microbiology, The Libyan Academy, Benghazi, Libya

Received: May 31, 2017 | Published: August 8, 2017

Citation: Bridan W, Baiu S, Kalfa H (2017) Non-Dermatophyte as Pathogens of Onychomycosis among Elderly Diabetic Patients. J Microbiol Exp 5(4): 00157. DOI: 10.15406/jmen.2017.05.00157

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of causative non-dermatophyte as causative agents of onychomycosis in elderly diabetics from the Libya.

Methods: The specimens were tested by direct microscopic examination using potassium hydroxide (20%) and culturing on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar and fungobiotic agar containing cyclohexamide and chloramphenicol.

Results: The most common cause of mycotic diabetic patients is different species of non-dermatophyte moulds isolated from 48 cases (41%). Yeasts were isolated from twenty six patients (22%). Dermatophytes were detected in only four patients (4%), and mixed fungi 6 (5%).There was no fungal growth in 28% of cases.

Conclusion: The most common cause of mycotic diabetic patients is different species of non-dermatophyte moulds. This study confirmed that diabetic patients are at a high risk of having or contracting onychomycosis. Managing onychomycosis in diabetics may require systemic antifungal treatment, physical measures and patient education.

Keywords:non-dermatophytes, onychomycosis, diabetic patients

DLSO, lateral subungual onychomycosis; PSO, proximal subungual onychomycosis; TDO, total dystrophic onchomycosis; KOH, potassium hydroxide; SAD, sabouraud’s dextrose agar

Aging is one of the predisposing conditions to develop mycotic nails,1–3 those often present chronic health problems such as diabetes peripheral circulation In fact in the elderly,3,4 the normal structure of the nail is altered producing changes in the color, thickness, flexibility, and shape resulting in some cases to marked dystrophic disturbances, mainly on the toenails. Since most of the functions of the nails are lost, the nail is increasingly exposed to trauma.3,5 and consequently to bacterial and fungal infections. Besides the effects on patient’s emotional, social, and occupational functioning6,7 untreated onychomycosis of the toenail can lead to patients experiencing physical impairment and pain8,9 to secondary bacterial infections and cellulites.10 So antifungal treatment should be exclusively reserved for those with a proved fungal infection.11

Samples collection

In the period of September 2013 to January 2014, a total of 116 patients attending the at the Sedee Hussein Polyclinic of Benghazi city were clinically diagnosed of having onychomycosis. Criteria for clinical diagnosis were onycholysis, discoloration or hyperkeratosis, Culture was positive in 84 of 116 diabetic patients with onychomycosis.

The specimens were obtained from clinically abnormal nails, by scraping the nail bed, the underside of the nail plate and the hyponychium, after cleaning the affected areas with 70% alcohol (Bode Chemie Hamburg - Germany). For each patient, a separate scalpel blade (Gowllands, England) and a sterile nail clipper (Rshengsl - China) were used for collection of the material to be examined. The different clinical patterns distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO), the proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), and the total dystrophic onchomycosis (TDO) were recorded separately.

Every collected specimen was divided into two parts for the following:

Direct microscopic examination

The collected specimen was placed in a test tube (Assistant, Germany) and drops of KOH (20% solution) were added using eye dropper to the glass tube and kept for 24 hours to dissolve the keratin. The collected specimen is then placed on a glass slide (Hamburrg-Germany), and covered by a cover glass (Hamburrg-Germany). Repeated KOH examination was performed before the specimen was considered as negative for direct microscopic mount.

Preparation of the medium and the agents

The specimen of each patient was placed in separate sterile Petri dish. Each specimen was inoculated on Sabouraud’s dextrose Agar (SDA), and Fungobiotic agar. The inoculated plates were kept in the incubator (MMM-Grafelfing, Germany) which was adjusted at 28°C and the cultures were examined every two days. The culture was considered negative if there was no growth after four weeks of incubation.

Microscopic examination was made by examining the preparations from different fungal growth mounted with the lactophenol cotton blue to reveal various structures which could be of great help in identification, especially the conidia which include the large separated macroconidia and the small celled microconidia. The macroconidia of each genus and species vary in shape and character of their walls which are generally characteristic for the species or genus.

Statistical analysis

Frequency tables and chart constructed for our data were analyzed statistically using the chi-square test. We assumed results statistically significant when P value is <0.005. The statistical analysis of the results was carried out according to the computer package (SPSS 18.0 version).

From the 116 diabetes patients, eighty four patients had onychomycosis confirmed by three different positive samples for direct examination and culture of nail scrapings. Among 84 diabetes patients, 35 were males and 49 females. The age was over 60 years to 93 diabetes patients.

From the 116 cases of suspected onychomycosis 84 (77.2%), non- dermatophytic molds and were the most common fungal elements isolated (57%, n=48) followed by yeast (31%, n=26), dermatophyte (5%, n=4), and mixed fungi (7%, n=6).

Among the NDMs, Aspergillus Niger was the most common isolate followed by Cladosporium spp. and Penicillium spp. Other alsolates were Aspergillus fumigates, Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium spp., Scytalidium sp, Alternaria spp., Rhizopus spp (Table 1).

Species |

Total |

% |

Aspergillus niger |

11 |

23 |

Cladosporium spp. p. |

10 |

21 |

Penicillium sp |

8 |

17 |

Aspergillus fumigatus. |

6 |

13 |

Aspergillus flavus |

4 |

8 |

Fusarium spp |

3 |

6 |

Scytalidium sp |

2 |

4 |

Alternaria spp. |

2 |

4 |

Rhizopus spp. |

2 |

4 |

Table 1 Non-dermatophyte moulds isolated as agents of onychomycosis.

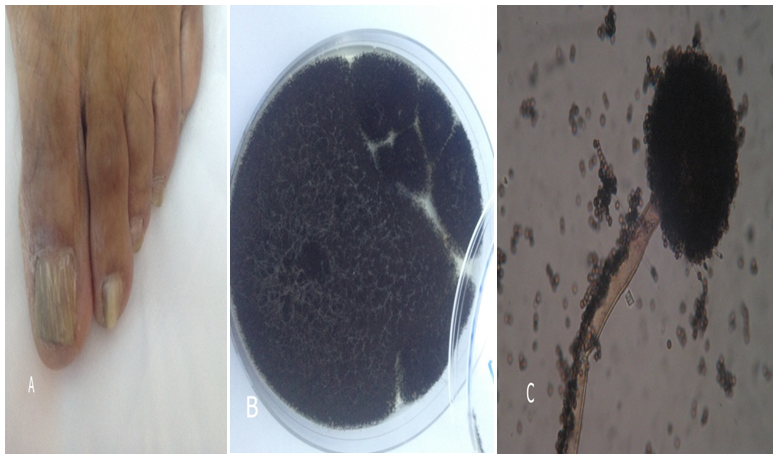

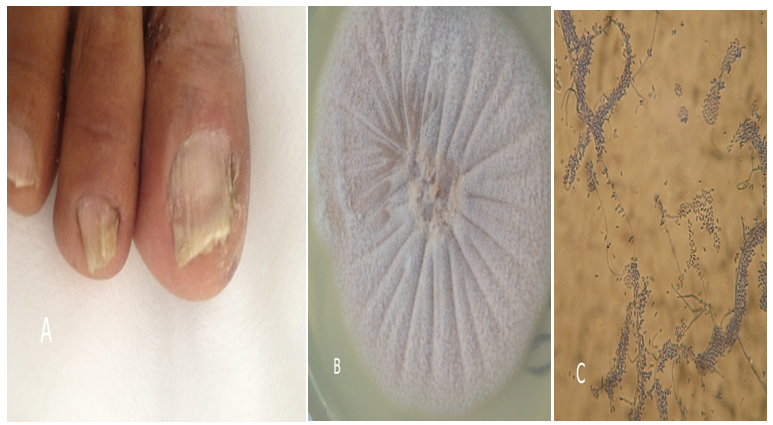

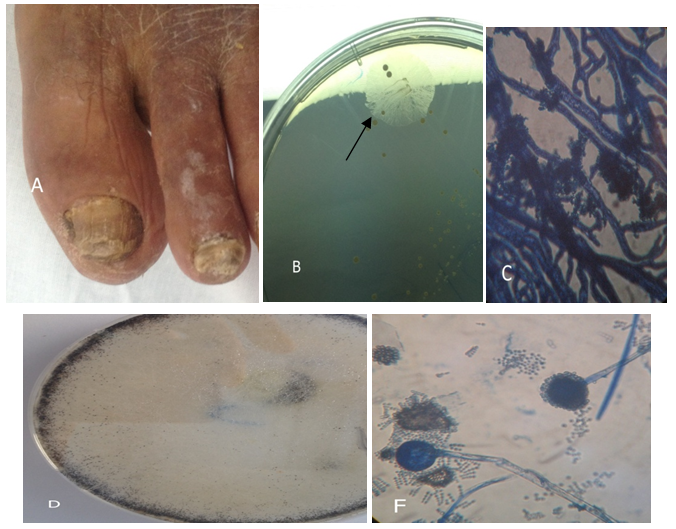

The most frequent nail change observed on toenails was discoloration of nail plate seen in (TDO) 44 (52%) of the patients Figure 1, followed by Distal and subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) 24(29%) Figure 2, and by proximal subungual Onycholysis (PSO) (19%) 16 Figure 3.

Figure 1 Example of nails affected by of Aspergillu niger.

(A) Total dystrophic onychomycosis.

(B) Aspergillus niger colony. (C) Microscopic, conidia spores on conidiophores.

Figure 2 Example of nails affected by of Fusarium spp.

(A) Distal and subungual onychomycosis.

(B) Fusarium spp. colony. (C) Microscopic curved separate macro conidia.

Figure 3 Example of nails affected by of Rhizopus spp.

(A) distal subungual onychomycosis and total dystrophic onychomycosis. (B) Rhizopus spp. colony. (C) Microscopic, Rhizopus. First grows rootlike structures at the base of the fungal strands (hyphae). (D) Rhizopus spp. colony. (F) Microscopic, sporangiophores, and sporongiospores.

Onychomycosis is a public health problem in patients over 60 years old, whose incidence is considered between 40% and 60% and it is increased with age.12–14 According to some authors, onychomycosis is more frequent in diabetic patients than in general population, especially in those suffering from sensibility disorders in soles, in toes, and in nails, conditions that could induce pressure necrosis of the skin by constrictive footwear.15,16 Gupta and coworkers in 1998 reported that a third part of the diabetic patients with pachyonychia presented onychomycosis.13 However, it is not well defined whether this onychomycosis is more frequent in diabetic patients than in general population In the present study the onychomycosis incidence was 84 in diabetic patients, similar to that reported by other authors.13,17

In other works, it seems that in these patients the diabetic was not the only risk factor for onychomycosis, since the ungual dystrophy was associated with other feet medical conditions.13 Total dystrophic onychomycosis (TDO) has been reported as the most destructive clinical form representing the end result of the evolution of any of the other five clinical forms in our study, this clinical presentation occurred in 44 cases, suggesting an advanced stage of the disease. In addition, the high number of involved toenails found on TDO cases also suggested a long-time exposure to pathogenic agents before sought for medical care.4

Onychomycosis characterized by a higher number of involved toenails, a longer duration of the disease, and significantly more advanced lesions. The development of chronic health problems, such as poor peripheral vascular which may predisposes to fungal nail infections.18,19 In our study, the same health conditions were mentioned by a high percentage of patients. Onychomycosis contributes to the severity of diabetic foot problems.20,21 Sharp, brittle nails can gouge the skin, creating a portal for entry of bacterial organisms.

The prevalence of onychomycosis among diabetics confirmed by culture was 77.2% (n=84).In earlier studies the prevalence ranged from of 17 to 30%.22–24 In this study, age greater than 60 years was not significantly associated with presence of onychomycosis. Other studies have also reported a higher prevalence of onychomycosis among the elderly.13,20,23

The most frequently isolated fungal element in this study was non-dermatophyte mould (57%, n=48), similar to an earlier study among the general population with clinically abnormal nails.25 Similar findings have been reported in Malaysia.25 Other studies have shown yeasts and dermatophytes as common pathogens isolated from diabetics with onychomycosis.13,26 This is probably because other factors, such as environment, level of humidity and the repeated contact with water influence the growth of particular fungi.27

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

©2017 Bridan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.