Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6453

Case Report Volume 9 Issue 2

Hospital Clínico Quirúrgico “Lucía Íñiguez Landín”, Cuba

Correspondence: Jose Cabrales Fuentes, Hospital Clínico Quirúrgico “Lucía Íñiguez Landín”, Holguín, Cuba, Tel +53 55995080

Received: September 21, 2022 | Published: November 23, 2022

Citation: Fuentes JC, Barbie SV, Cabalé ALM. Imaging and histological approach to the diagnosis of pulmonary lesions by COVID-19: case report. J Hum Virol Retrovirol. 2022;9(2):54-56. DOI: 10.15406/jhvrv.2022.09.00249

A 52-year-old white female patient, a teacher by profession, with no personal pathological history of interest, was admitted to the intensive care unit of the "Lucía Íñiguez Landín" Clinical Surgical Hospital with pneumonia due to COVID-19, for which received several treatments persisting after 20 days of the same a marked severe restrictive ventilatory pattern without achieving improvement and died. Digital radiography images and chest computed tomography images were obtained, and a pulmonary histological study was also performed. The novelty of the case is given by the current relevance of the use of imaging and histological studies of this pandemic entity that has spread rapidly throughout the world whose histopathological changes are not fully understood, which undermines clinical identification adequate treatment of patients and the implementation of effective therapeutic strategies, which is why this article was prepared with the aim of showing the findings in the diagnostic imaging corroborated with histology.

Keywords: covid 19, imaging, histology

WHO, world health organization; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; RALE, radiographic evaluation of pulmonary edema; TF, tissue factor

At the end of December 2019, several cases with atypical pneumonia that progressed to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) occurred in the city of Wuhan, Hubei province of China. The causal agent of this disease called COVID-19 was a new coronavirus: SARS-CoV-2, with a great capacity to spread. The rapid expansion of the disease has put the health systems of many countries to the test in a short time. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a state of pandemic and Cuba reported the first three cases, all imported from Italy.1

The clinical behavior of the disease has a wide spectrum that ranges from asymptomatic cases or mild disease, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure.1 The infection evolves in phases: a first phase of early infection or viral replication, a second of pulmonary invasion or pneumonia and a third called hyper inflammatory and procoagulant, in the latter the phenomena of thrombosis of small vessels are frequent, as well as cardiac arrhythmias, septic shock and dysfunction of multiple organs.1

Although the diagnosis of COVID‑19 is based on the identification of the virus through laboratory tests, such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, medical imaging is commonly used to evaluate patients in the different phases of the disease, particularly in moderate cases serious or critical.

Consistent with this, medical imaging studies are of vital importance in guiding the doctor in decision making, but they are the histological examinations the gold standard to determine why and how death occurs. The definition of the pathophysiology of death is not limited only to forensic considerations, but also generally provides valuable clinical and epidemiological information. Selective approaches to postmortem diagnosis include limited sampling during full autopsy; they are also useful in controlling disease outbreaks, and provide unique knowledge to manage appropriate control measures.2

B.ogaert et al, in this sense would express:

…history suggests that the battle against SARSCoV-2 and other coronaviruses is still “in its infancy”, and that we will have to learn lessons not only to be better prepared, but also to know about specific aspects of this virus, and more generally.3

A 52-year-old white female patient, a teacher by profession, was presented no background personal pathological of interest, that initiates symptoms after contact with an asymptomatic carrier of COVID-19 turning out to be positive to the virological study by Transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for its acronym in English (RT-PCR) completes initial treatment with corticosteroids, later admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) of the “Lucía Íñiguez Landín” Surgical Clinical Hospital with COVID-19 pneumonia by increased work of breathing, presenting progressive dyspnea and hypoxemia. Yes I took Aron chest x-ray digital showing Heterogeneous peripheral opacities of both lungs were corroborated by ground-glass image of the chest tomography.

On day 20 of stay with marked severe restrictive breathing pattern without achieving improvement and dies.

Personal pathological history: history or previous surgical interventions are not collected.

Family pathological history: mother with arterial hypertension.

Clinical findings (physical exam) were collected in the first 10 days cough, fever, headache, and anosmia. On admission to the ICU, he showed RF: 35 breaths/min, PO2/ FiO2 ratio <185, Sat SHB/ FiO2 <200, confusion, disorientation, use of accessory muscles of respiration, intercostal or subcostal in drawing.

Diagnostic evaluation

Laboratory exams: increased urea and creatinine levels, blood count with severe lymphopenia.

Imaging evaluation

Digital radiography: Thorax p to quantify pulmonary involvement, a severity score was calculated by adapting and simplifying the Radiographic Evaluation of Pulmonary Edema (RALE) score proposed by Warren et al., where eight points are considered according to the radiological extent of pulmonary involvement. For its calculation, each lung is visually divided into four parts, starting from the pulmonary hilum as the midpoint. Each resulting box will correspond to 25% of the lung parenchyma and each lung will be scored according to the percentage of extension of the consolidations or radiopacities, distributed as follows Normal (0 point) Mild (1-2 points), Moderate (3-6 points) and Severe (more than 6 points)4 (Figure 1).

Computed axial tomography: The CO-RADS classification was taken into account, which is a standardized notification system for patients with suspected COVID-19 infection; this assigns a level of suspicion for the disease according to the findings found in the CT image. These range from very low, CO-RADS 1, to very high, CO-RADS 5, and CO-RADS 6, which corresponds to patients with typical findings and positive PCR4 (Figure 2).

Histological evaluation

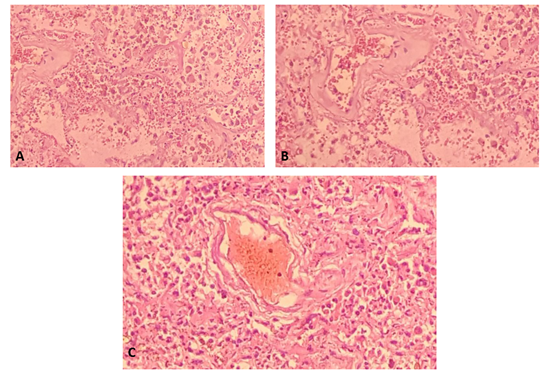

Post-mortem autopsy: it was performed to confirm severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, analyzing histological samples of lung tissue obtained by necropsy, determining the exact cause of death and recognizing histological patterns that eventually contribute to guide clinical management (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Histological changes observed in post-mortem autopsy.

A) Section of lung tissue shows pulmonary alveoli filled with acute inflammatory cells, macrophages. Increased fibro connective tissue in some alveolar septa and hyaline membrane formation resulting in respiratory distress.

B) Interstitial fibrosis, rupture of alveoar septa with acute intralaveolar and septal inflammatory response.

C) Vascular thrombosis associated with an inflammatory process and interstitial fibrosis.

Techniques and procedures used

Therapeutic intervention

The patient complied with the established national action protocol for covid-19 version 1.6,8 requiring advanced airway management receiving mechanical ventilation, sedation, analgesia, muscle relaxant as well as protective ventilation. Position changes were made to avoid microatelectasias.

Although the procedure of choice is PCR, it is also necessary to have rapid, simple and ideally high sensitivity and precision tests that can be performed on a large scale. The goal is a diagnosis, early, for better management (isolation and treatment if necessary) and monitoring of patients, the application of measures to prevent and control the expansion and epidemiological surveillance.5

Imaging studies, essential in most healthcare processes, play a key role in the management of patients with COVID-19 infection.5

Radiographic findings suggestive of COVID-19 are: focal opacities with a clear increase in density and with margins less defined than a nodule; focal or diffuse interstitial pattern and focal or diffuse alveolar-interstitial pattern.4

Tomographic findings in patients with COVID-19 have been classified as: typical, that is, there are multiple ground glass opacities of peripheral and basal distribution, vascular thickening, cobblestone pattern or disordered cobblestone (crazy paving); atypical findings, that is, para hilar, apical ground-glass opacities, and lymphadenopathy; and highly atypical findings, or in other words, cavitation, calcifications, nodular pattern, budding tree, masses, and pleural thickening.4

The histological images translate what was evidenced in the imaging studies such as: diffuse alveolar damage in the organization phase with fibrosis, which was decisive for making therapeutic decisions, marking the patient's prognosis. In addition, the evidence SARS-CoV-2 testing can be done at autopsy. Autopsy findings such as diffuse alveolar damage and airway inflammation reflect true virus-related pathology. Other findings represent processes that are superimposed or not related to the disease under study. In this case, the patients with COVID-19 presented diffuse alveolar damage with the formation of hyaline membranes, mononuclear cells, and macrophages that infiltrate the air spaces, also with diffuse thickening of the alveolar wall.2

Wichmann et al also found a high incidence of thrombotic events, which suggests that the COVID-19 virus induces severe endotheliitis and abnormal activation of the coagulation cascade. For this reason, further studies are required to explain these findings, and eventually achieve a possible therapeutic intervention in the near future.2,6 Finally, Merad described micro thrombi at different levels in patients with COVID-19: lungs, lower extremities, hands, brain, heart, liver and kidneys, suggesting that coagulation activation and intravascular coagulation are data of an organic lesion in sepsis that is mainly associated with inflammatory cytokines and with the participation of the pathway tissue factor (abbreviated TF; also called CD142 or coagulation factor III) and which undoubtedly contributes to the greater severity of patients.2,7

In summary, we can infer as a conclusion that imaging studies demonstrate wide utility in the diagnosis and monitoring of COVID 19, a fact that is evidenced in the histological study where there is largely a correspondence between the two diagnostic modalities, the latter fulfilling the medical precept that death can teach us not only about disease, but can also help us with its prevention.

Jose Cabrales Fuentes: Literature review, data collection, preparation of figures, writing.

None.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2022 Fuentes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.