Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6453

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 5

1Laboratório de Farmacogenômica e Epidemiologia Molecular, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Brazil

2Laboratório de Patologia e Biologia Molecular, Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil

3Laboratório MICRO, Serviço de Anatomia Patológica e Citopatologia, Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Brazil

Correspondence: Sandra Rocha Gadelha, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Campus Soane Nazaré de Andrade – Rodovia Jorge Amado, km 16, Salobrinho, CEP 45662-900, Ilhéus – Bahia, Brazil

Received: October 26, 2020 | Published: November 19, 2020

Citation: Santos FP, Costa GB, Santos UR, et al. Could HPV be implicated in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma in Bahia, Brazil? J Hum Virol Retrovirolog. 2020;8(5):125-127. DOI: 10.15406/jhvrv.2020.08.00232

Tobacco use and alcohol consumption are the principal risk factors implicated in head and neck cancers, however, the presence of HPV has also been associated. Here, we sought to correlate risk factors such as socio-demographic and behavioral variables, and the presence of HPV, to head and neck cancer occurrence. During August 2016 – December 2017, paraffin embedded samples from two anatomic pathology services of two populous cities in the state of Bahia were analyzed. To detect the presence of HPV, the formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue samples were initially deparaffinized for subsequent DNA extraction. Nested-PCR was applied to detect HPV DNA, and viral subtyping was confirmed through specific PCR primer and sequencing. Most of the patients confirmed being smokers and drinkers. HPV was detected only in 7% of the samples, a histopathological diagnosed benign lesion of laryngeal papilloma (HPV 11), and a malignant lesion of the hard palate (HPV type not specified). Our findings indicated that tobacco use and alcohol consumption were correlated as the highest risk factors for the development of neoplasms. Although HPV prevalence was low, we could not neglect HPV involvement in head and neck cancers in individuals from Bahia State. Furthermore, HPV+ cancers respond better to therapy, therefore, defining the type of tumor is important to determine the most effective treatment.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, human papillomavirus, epidemiology, tobacco usage, alcoholism

Head and neck cancer (HNC) are a worldwide public health burden, presenting high mortality rates primarily in less developed countries, with an estimate of 833,000 new cases expected globally by 2020.1,2 HNC is a common term that refers to neoplasms affecting from below the skull base to the region of thoracic inlet, including several malignancies that originate in the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, salivary glands, oral cavity, naso-pharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx.1 The majority cases of HNC is related to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), that occurs in 90% of cases.3

The most important risk factors contributing to the development of HNC are the concomitant consumption of tobacco and alcohol presenting a strong dose-response relationship.1,4,5 Alcohol itself is classified as class I carcinogen6,7 and can also act as a solvent for other carcinogens substances such as cigarette smoke and exposure mucosa to these toxic agents, increasing the absorption of the carcinogenic substances.8

Exposure to the human papillomavirus (HPV), especially the high-risk (HR) types such as HPV-11 and -16, has also been associated with HNC.9–11 HPV is one of the most common sexually acquired infections worldwide and the high incidence of HPV-associated HNC could be explained, in part, by the sexual behavior.12 Some studies have indicated that oral sex is a potentially risk-related practice for HPV infection and development of HNC.13,14

Although the occurrence of HNC in Brazil is growing progressively,15 studies that correlates its occurrence with HPV infection in Brazil are still poor explored. Furthermore, there is no available data regarding the epidemiology of head and neck cancer in the State of Bahia. The present study aimed to assess possible risk factors for head and neck cancers, including the presence of HPV.

A cross-sectional study was carried out from August 2016 to December 2017 with individuals attended at the Micro-Service Laboratory of Pathology and Cytopathology, in Vitória da Conquista City, and Laboratory of Pathology, Calixto Midlej Filho Hospital, in Itabuna City. Vitória da Conquista (14° 51′ 57″ S, 40° 50′ 20″ W) and Itabuna (14º 47' 08" S, 39º 16' 49" W) are respectively the third and the fifth largest cities in the State of Bahia, and important centers in healthcare assistance for a large population located in the surrounding cities and rural areas of the State.

Participants with head and neck lesions were invited as volunteers and biopsy samples were collected in paraffin blocks. Additionally, all participants were submitted to a semi-structured questionnaire to elicit data on demographics and behavioral practices. These data were converted to variables and tested for correlation to the positive or negative results related to HPV infection and histopathology results.

Paraffin embedded samples were submitted to DNA extraction by using the PROMEGA RealiPrep™ FFPE gDNA Miniprep Kit, according with manufacturer’s instructions. To detect HPV DNA a nested-PCR (primers MY09/MY11 followed by primers GP5+/6+) was applied using adapted protocols as previously described.16,17 Briefly, in the first round reaction, the following reagents were used: 14.65µL of Milli-Q water; 2.5μL of 10x buffer (500 mMKCl and 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]); 0.75μL MgCl2 50mM; 4μL from the “pool” of dNTP (1.25 mM); 0.3 μL of MY09 primer (10pmol/μL); 0.3 µLof MY11 primer (10pmol/μL); 0.5μL Taq polymerase [Invitrogen®] (1U/µL) and 2.0μL of the solution containing the DNA sample (final volume of 25μL). The cycling conditions were: 1 cycle of 1’ at 94°C followed by 40 cycles of 1’ at 95°C, 1’ at 55°C and 1’ at 72°C, followed by 10’ at 72°C for final extension. In the second round reaction, the following reagents were used: 28.6 μL of Milli-Q water; 5 μL of 10x buffer (500 mM KCl and 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5] ); 1.5μL MgCl2 50 mM; 8μL from the “pool” of dNTP (1.25 mM); 0.70μL of GP5+ primer (22.5 pmol/μL); 0.7µL of GP6+ primer (18.9 pmol/μL); 0.5μL Taq polymerase [Invitrogen®] (1U/µL) and 5.0µL of the solution containing the first round (final volume of 50µL). The cycling conditions were: 1 cycle of 4’ at 94°C followed by 40 cycles of 30’’ at 94°C, 30’’ at 55°C and 30’’ at 72°C, followed by 8’ at 72°C for final extension. Additionally, all samples that tested positive in the previous nested-PCR were analyzed for the presence of eight HPV subtypes, which included 6/11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 58, as previously described.18

The individual was informed about the project in the collection unit and invited to a discussion for greater clarity. An Informed Consent Form was issued. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, under the registration CAAE: 55257316.2.0000.5526.

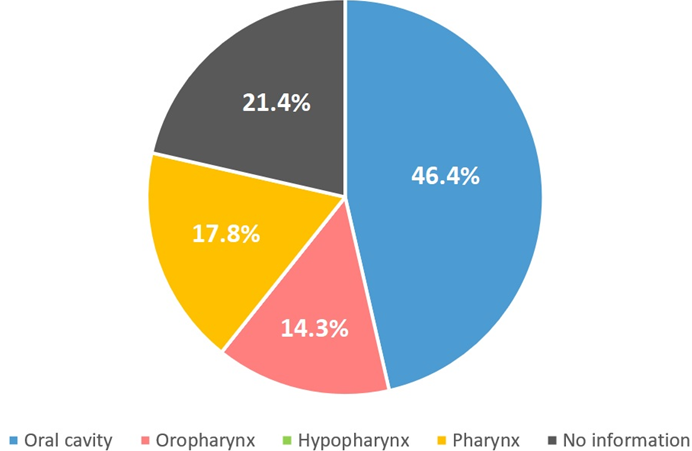

A total of 28 samples of head and neck tumors were included in the study. The median age of individuals was 62.1 years (ranging from 39 to 86 years). Men represented 53.6% of the population. Most samples were collected from the oral cavity (46.4%), while others were collected from oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx. Approximately 70% of samples were malignant cases, being diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Regarding the main risk factors associated with the malignant tumors detected, 53.3% of individuals reported they were alcohol consumers and smokers (combined) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of collected samples by anatomic site. A total of 13 samples (46.4%) were collected from oral cavity, 4 (14.3%) from oropharynx, and 5 (17.8%) from pharynx. There was no information for 6 samples and there were no samples collected from hypopharynx.

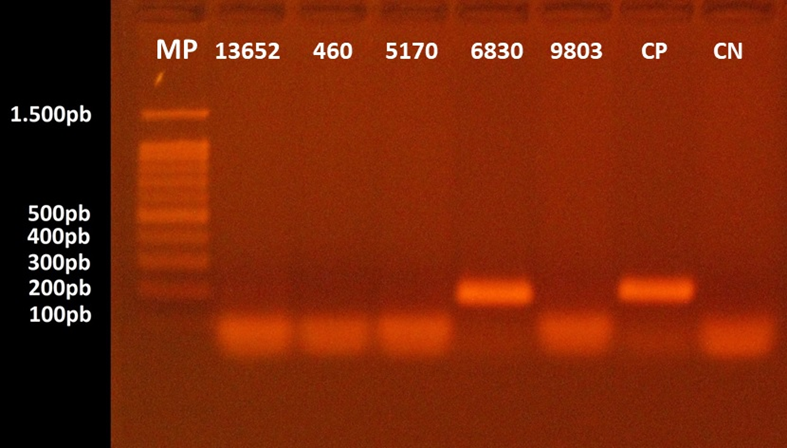

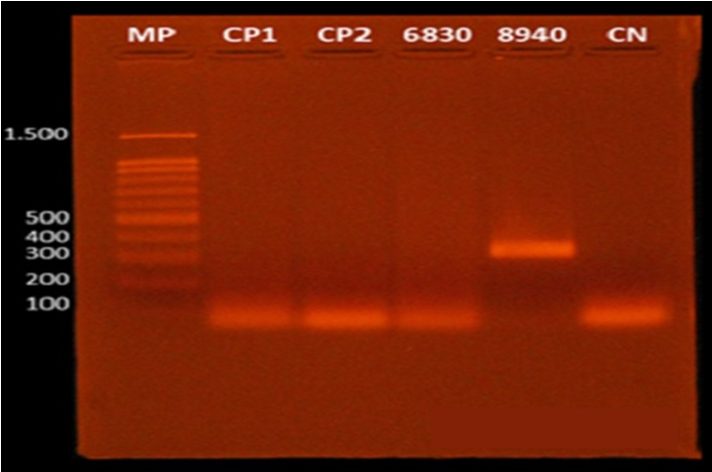

Only two individuals tested positive to HPV DNA. The first was a man, aged 48 years old, diagnosed with a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity. This patient also reported to be a smoker and drinker. The second patient was a woman, aged 39 years old, with no smoking or drinking habits, and diagnosed with papilloma, one of the most frequent benign tumors of the larynx. Subtyping analysis confirmed HPV 11 infection (Figure 2 & 3).

Figure 2 Agarose gel electrophoresis for the separation of HPV DNA fragments. The numbers 13652, 460, 5170, 6830, and 9803 correspond to patients’ identification code. HPV DNA was detected in the sample 8490 which was collected from the hard palate of a 48 years-old male patient diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma. MP: molecular marker ranging from 1.500 to 100 base pairs; CP: positive control; CN: negative control.

Figure 3 Agarose gel electrophoresis for the separation of HPV DNA fragments. HPV 11 DNA was detected in the sample 8490 which was collected from the hard palate of a 39 years-old female patient, with no smoking or drinking habits, diagnosed with papilloma of the larynx. MP: molecular marker ranging from 1.500 to 100 base pairs; CP: positive control; CN: negative control.

Generally, the demographic profile of HNC patients is male, among 40–69 years old, smokers and/or alcohol consumers, and at an advanced stage of diagnosis.19,20 However, some studies have shown an increase of HNC in young individuals, with no history of cigarette or alcohol consumption, indicating that other important risk factors (such as HPV infection) could be implicated.4,15,21

In developed countries, such as in the United States of America (USA), a decrease in alcohol and cigarette consumption has led to a decline in the incidences of oral cavity, larynx, and hypopharynx cancer.7 Up to 25% of HNC cases diagnosed in the USA are independent of cigarette use, being attributed to HPV infection.22 In Brazil, on the other hand, the estimates for the number of HNC are still poorly explored, although HPV infection has contributed to the increase in the incidence of HNC in recent years.23

According to Lewis and colleagues, HPV+ and HPV- HNC differ in both demographic profiles and in risk factors.24 While HPV+ HNC is more related to sexual behavior, HPV- cases are strongly associated with alcohol and cigarette consumption. It has also been suggested that HPV-associated oral cancer could be similarly associated to the pathogenesis of HPV infection in the cervix, as the lining epithelium of the upper digestive tract resembles vaginal and ectocervix epithelium.25

In the present study, the prevalence of HPV in HNC samples was extremely low. However, other studies performed in Brazil also found low prevalences of HPV infection in HNC, ranging from 4.4% to 8.8%.26–29 Curiously, we found two positive cases of HNC with no history of cigarette or alcohol consumption that tested negative for HPV infection. This finding draws attention for false-negative cases which cannot be ruled out, since the molecular detection of HPV from paraffin samples could be hampered by sample processing. Our study has limitations that are important to its interpretation. We were not able to obtain a great number of samples due to the lack of adherence of many patients to the study. Furthermore, we also missed epidemiological information of six individuals. The incidence of HPV in the evaluated samples may have been underestimated due to the paraffinization and deparaffinization process that could have compromised HPV DNA detection.

The presence of HPV in individuals with head and neck cancers is apparently low in Bahia State. Tabaco use and alcohol consumption are important risk factors for HNC, however, our findings pointed out the occurrence of HPV infection in HNC cases. As HPV positive HNC cases respond better to therapy, additional studies are need to better understand the real prevalence in Bahia State, as well as to guide health authorities and decision makers the most effective treatment approach.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

©2020 Santos, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.