Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

PhD from the Sorbonne University, Paris, France

Correspondence: Patrice Foutakis, 55bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75006 Paris, France,

Received: December 07, 2020 | Published: February 25, 2021

Citation: Foutakis P. The church of Santa Maria de Valverde in Modon. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2021;6(1):1-4 DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2021.06.00237

There was a church in Modon, destroyed in the nineteenth century, that has never been the object of a survey, nor her position has been detected. This paper highlights the importance of this church, locates her position and explains the reason she was abandoned and finally she disappeared with her stones reused as building material.

Keywords: middle ages, history, paleography, catholic church, architecture, venice, modon

The strategic location of the castle and bay of Modon, at the south-westernmost extremity of the Peloponnese in Greece, was the cause of claims and military conflicts against Spartans in 600 BCE, Athenians in 456 BCE, as well as Mauritanians and Romans in 31 BCE. Byzantines had to fight against Saracen and Genovese pirates in 881 and again in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Franks in 1204, Venetians in 1207 and 1686, Turks in 1500 and 1715, Hospitaller knights of the Order of Malta in 1531 and French in 1828 were also military involved in Modon. Her glorious period was under Venetian rule from 1207 to 1500 and from 1686 to 1715. The castle, today under restoration, presents significant archaeological and architectural interest.

Given the geographic, commercial, political and military significance of Modon, mendicant orders had establish their convents and churches in the castle, such as the house of the Preaching Dominican Friars Order and the house of the Franciscan Friars Order. Furthermore, as a leading port of call for the Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia in the Mediterranean Sea, Modon had many churches within and outside the castle: for the Orthodox native Greeks, for the Catholic masters from Venice, but also for the merchants, the travelers, the pilgrims to and from the Holy Land, the scholars crossing the seas, and the civil or military crews from ships docking into the port of Modon. Many reports emphasize on the importance of this port: Leonardo Frescobaldi described Modon in 1384 as a port for the navigation of all nations; Roberto da Sanseverino admitted in 1458 that Modon confirmed her reputation as the biggest and best refuge port for all kind of ships; Felix Faber expressed in 1483 his admiration for the port of Modon and the shape of her castle, just to mention only these testimonies.

One of the extramural churches at the castle of Modon was that of Santa Maria de Valverde alla spiaggia, meaning Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore, as she is quoted in numerous manuscripts.1 The significance of this church is stressed through the correspondence between Venice and the Venetian administration of Modon. In one of these manuscripts, dated 22 August 1453, the Senate of Venice gave the order to the Governor of the castle Alessandro Marcello, and to both Counselors, who were in fact Vice-Governors, Alvise Tagliapietra and Filippo Barbarigo, to take very good care of this church and the way the feast of the Assumption of Virgin Mary was celebrated. It is noteworthy to mention the fact that a few weeks before this order, took place the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman empire on 29 May 1453.2 The presence of Turks became more and more threatening to the Venetian territories in Greece, while outside the castle of Modon, where the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley was built, most of the inhabitants were Gypsies and Jews, most of the Greeks and all the Venetians in Modon living within the castle. Therefore, the order of the senators of Venice to the administration of the castle had an urgent and determining character for this Catholic church located outside the safe walls of the castle.

The attention paid by the inhabitants to Saint Mary of the Green Valley church is also revealed in many notarial acts. Venetian notaries, established and working in Modon, left their archives where citizens of Modon mention the church in their wills. Enrico Furlan, according to his will on 12 March 1336, left money for the church of Saint Mary outside the castle under the condition that after his death four prayers should be celebrated in his memory. The widow Agnese Rubeo did the same in her will on 21 August 1336, as well as the goldsmith Nicoletto from Euboea in his will on 22 November 1347, while the monk Marino Soranzo, following his will on 12 January 1348, “left 300 hyperpyres for the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley which is outside the castle of Modon, near the seashore.” Their testimonies make clear that this old and important church was founded at the beginning of the fourteenth century, at the latest, and most likely in the thirteenth century.3–6

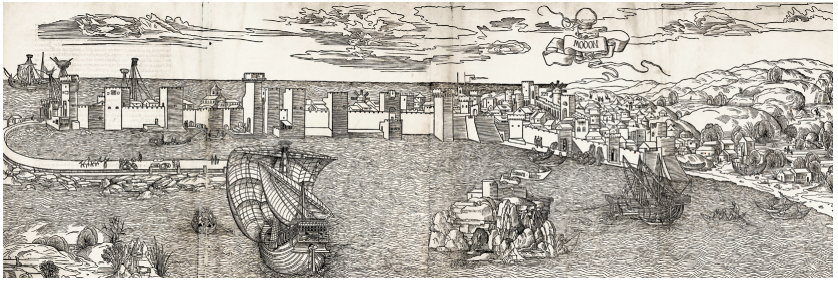

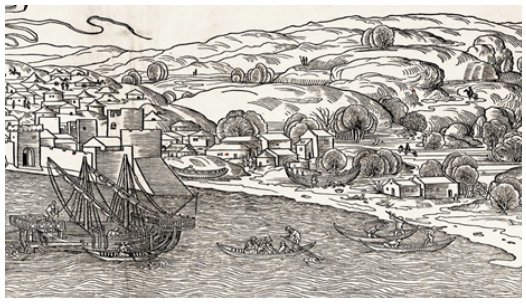

The only reliable depiction of the castle and port of Modon before 1500, the year she felt to the sultan Bayezid II, is a woodcut made by Erhard Reuwich and published in 1486 with the incunabulum account of the pilgrimage to the Holy Land by Bernhard von Breydenbach, entitled Opusculum sanctarum peregrinationum ad sepulcrum Christi venerandum. Both Breydenbach and Reuwich stayed in Modon on 15 and 16 June 1483 on their way to Jerusalem, and it was those two days that the designer and printer Reuwich made his detailed drawings that allowed him to realize a most realistic woodcut of Modon (Figure 1). Outside the castle, on the right end of the woodcut, are depicted buildings and tents that existed at the time (Figure 2). Two buildings have an additional extension looking east, that is towards the harbor of the castle, but only one of them is semi-circular and concerns a low building like a church; the other building with an extension is a double-floor vertical construction and certainly not a church.7 Details of defensive architecture of the castle still existing today allow to check out the reliability of this woodcut: it is a very realistic work and therefore a priceless testimony for the aspect of Modon before the Ottoman occupation. Hence, the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore was this building with an entrance from the west and an apse around the altar oriented east. Nothing survived from this church and her position was never located at a place today occupied by the modern village of Modon.

Figure 1 Erhard Reuwich, View of Modon. Woodcut first published in 1486 in Bernhard von Breydenbach, Opusculum peregrinationum ad sepulcrum Christi venerandum. It was realized after detailed drawings Reuwich made during his stay in Modon on 15 and 16 June 1483. (Photo courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France).

Figure 2 Detail of Reuwich’s woodcut. The church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore (Santa Maria de Valverde alla spiaggia) is the construction with the apse, oriented to the sea, that is east like the apses around the altar of Christian churches. (Photo courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France).

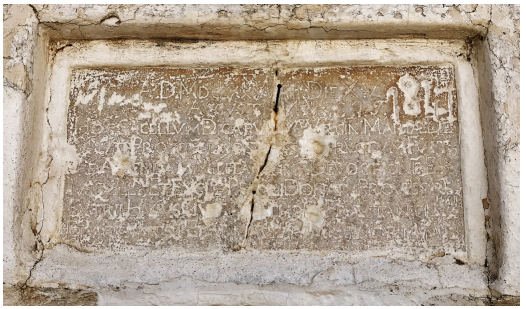

Embedded on the facade of a house in the village of Modon stands today an inscription incised on a rectangular limestone, 37 cm by 71 cm, plus a frame of 4 to 5 cm (Figure 3). Some words and letters of the inscriptions are weathered, and what can be read gives the following:

AD MDCLXXXVIIII DIE XV

AVGVSTI MV

HOC SACELLVM DICATVM VIRGINI MARIAE DE

SALVTE PROTONOTARI NOS ………….RVCTVM FVIT

ADA……..… MILITA …IVM DEVOCTIONE EX

IVSSV ILLMI ET EXCLMI PRIORI DONATI PROVISORIS

EXTRIB HVIVS CIVI…… ….THO… PRAESTANTISMI

ET VIGILANTISMI ET AD POSTERVM MEMORIAM

Figure 3 The inscription of the papal protonotary dated 15 August 1689, today embedded on the facade of a house in Modon. Limestone, 37 cm by 71 cm, plus a frame of 4 to 5 cm. (Photo Patrice Foutakis).

Although the marks of bullets destroyed part of the text, what is left makes perfectly sense. A protonotary, a high papal official, on the occasion of his visit to Modon, made a donation to the chapel of Saint Mary on 15 August 1689, following the tradition of past distinguished donators, who will remain in memories as watchful protectors of Modon.8–11 In August 1689, Governor of Modon was Alessandro Priuli, and Antonio Zen was the Provveditore, the Governor-General of the Venetian Army in Peloponnese, the highest officer in the Venetian Kingdom of Morea.

The castle was liberated from the Turkish domination in 1828 by the French expeditionary Army of Morea. Except a partial restoration of the castle undertaken by French architects and engineers from 1829 to 1833, a new urban planning was proposed in 1829 by the French army. From 1830 onwards, the new village of Modon was built outside the castle according to this plan (Figure 4). What already existed was drawn in rose watercolor, and what was proposed as the aspect of a new, modern village, was indicated in yellow watercolor in this urban plan. Among the existing constructions in rose, is drawn a building with an orientation west-east and an apse on the east end (Figure 4); the orientation and the apse leave no doubt that this building was a church. Since this construction, still existing in 1829, did not survive a long time after this plan, it means that this church was in a bad condition, maybe in ruins in 1829, and was demolished sometime during the nineteenth century. The position of this church was near the Siloso river and the fertile cultivated fields along the river formed a real green valley. The existence of these fertile fields, irrigated by the river, is mentioned in many reports and depicted in plans or illustrations. In the Middle Ages, this position was much closer to the sea, for the sea lever was higher, reaching the walls of the castle and covering what is today a sandy beach (Figure 5). In other words, the church indicated on this urban plan was that of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seaside.

Figure 4 Detail of the urban plan to scale of Modon made and signed by the engineer lieutenant colonel Joseph-Victor Audoy, commander of the Engineering section of the French expeditionary Army of Morea, and the lieutenant Alexandre Dubard on 4 May 1829. The existing buildings are indicated in rose watercolor and the constructions to be made, in yellow blocks. The red arrow, added in this figure, indicates the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore. The smaller construction within the church is the Medieval church depicted on Reuwich’s woodcut and the inscription of 1689 is referring to. (Photo courtesy of the Greek Ministry of Environment).

Figure 5 View from southeast of the castle of Modon. The old collapsed mole, parallel to the castle, can be seen under the sea surface. Until the nineteenth century, the sea level was higher, reaching the defensive walls and covering what is today a sandy beach. (Photo courtesy of Dimitris Smyrlis).

The dimensions of the church of Santa Maria de Valverde alla spiaggia, drawn in the French urban plan (Figure 4), are impressive: the precise scale of this plan gives a construction of 46 m in length and 25 m in width. This dimension is too big for a church in Medieval Modon and can hardly match with the inscription of 1689 referring to a small church or a chapel, sacellum; not to mention the cathedral of Saint John the Evangelist within the castle, which was the bishopric see of Modon. This cathedral was measured and depicted on an engraving and on an architectural plan to scale made by the architect Guillaume-Abel Blouet, chief of the architecture and sculpture section of the French scientific Expedition of Morea in spring 1829: her width was 20.5 m and the length 28.5m, with a total length of 44 m including the atrium in front of the cathedral. If the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore was 46 m in length from the beginning, and moreover outside the castle, she would have appeared as a big building in Reuwich’s woodcut instead of a rather small church with her apse. On this woodcut is also depicted correctly, in her realistic dimensions, the cathedral of Saint John the Evangelist, between the third and fourth towers from the left (Figure 1). The French urban plan of 1829 shows that the big church, 46 m in length, is containing a smaller construction, 17 m in length and 9 m in width (Figure 4). This was the first church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore, later enlarged with a bigger church around the old one. If this enlargement took place before 1689, year of the inscription (Figure 3), then this inscribed limestone was meant to refer to the old church as a chapel of the big, enlarged church. If the enlargement was undertaken after 1689, then the inscription was made for the small old Medieval church, since the bigger one was not yet constructed.

The inscription suffered two damages. While it was in the church, it became the target of Turkish guns, with the bullet marks still clearly seen in the limestone (Figure 3). Since the inscription bears the year 1689, this damage happened during the second Ottoman occupation of Modon between 1715 and 1828. The second damage comes from a Greek hand adding the year 1841 and the letters ε λ ς. They are obviously the initials of the person who reused the inscription in 1841: the initials of his first name E, his father’s name L, and his family name S. This occurred most likely when the abandoned church collapsed or was demolished. If so, the year 1841 is the date the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore disappeared. By applying on a modern satellite photograph of Modon the position of the church according the French urban plan to scale in 1829, I realized that the house where the inscription is embedded today is almost at the same place the church was standing from the thirteenth or fourteen until the nineteenth century (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Detail of a satellite photograph of the village on Modon on 28 April 2017. The red line indicates the position of the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore, and the red circle goes around the house with the embedded inscription. (Photo Google Earth).

The castle of Modon suffers from the elements: it is the place strong currents of the Ionian Sea cross even stronger currents of the Mediterranean Sea. As a result, extreme weather phenomena occur at the Modon bay with most violent winds, raging tempests and torrent rains with thunderbolts. A further demonstration of nature’s strength is the fact that the area presents a regular tectonic activity with frequent earthquakes. Thus, through the centuries and the millennia, there have been many fluctuations of the sea level and changes of the geomorphological layout of the shoreline at the Modon bay, and therefore the archaeological importance of the place is not only in the castle but also at the bottom of the sea with numerous shipwrecks containing most significant archaeological items. Furthermore, Modon also suffered from human activity.12 Military attacks, massive civil destructions and the presence of different religious beliefs had a negative impact on the archaeological, architectural and cultural inheritance of Modon.

As far as the church of Saint Mary of the Green Valley near the seashore is concerned, the decision of the Venetian Senate on 22 August 1453 and the initiative of the papal protonotary on 15 August 1689 were meant to maintain and reinforce the Catholic worship in this church. However, until 1500, most of the inhabitants in the neighborhood around the church were Gypsies and Jews, while during the two Ottoman occupations in 1500-1686 and 1715-1828, the main neighbors of Saint Mary of the Green Valley were Orthodox Greeks. Hence, an important church of one of the leading castles by the Mediterranean Sea disappeared. What is left, is an inscription of a Catholic protonotary, reused in a house of an Orthodox Greek.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2021 Foutakis. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.