Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 4

Departments of Humanities and Fine Arts, St. John International University, Italy

Correspondence: Elisa Lanza Catti, Departments of Humanities and Fine Arts, St. John International University, Italy

Received: June 05, 2017 | Published: August 2, 2017

Citation: Catti EL. Sustainability educationi the humanities: the impact of antiquity through art history. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2017;1(4):139-144. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2017.01.00024

The paper investigates the importance of Sustainability Education and the role of Antiquity in contemporary society through a specific case study. The research involves the analysis of the close surroundings of St. John International University’s campus, an American University once located in Vinovo, a small village near Turin (northern Italy); the small institution, founded in 2008, unfortunately did not survive the economic crisis and eventually closed in 2014.

The local environment of the former campus hosts precious evidence of the impact of Antiquity on the arts, especially in the Renaissance and Neoclassical periods. Undergraduate students involved in the project discovered several examples of the influence of Classical culture on the architecture of the 15th-century Della Rovere castle and other relevant buildings in the surroundings. While addressing questions on the global level pertaining to Sustainability and Art History, they started acting locally, to become responsible stewards of such a precious cultural heritage.

Keywords: sustainability education, renaissance, antiquity inheritance, della rovere castle, vinovo

Classical tradition has played a significant role in the construction of western culture, by influencing several disciplines from literature and the arts to politics and science. Modern society, however, is increasingly less informed about the precious heritage received from their Classical ancestors. Charles Martindale1 defined the reception of classical antiquity as “a two-way process… in which the present and the past are in dialogue with each other”. Unfortunately, however, too often modern society seems to lose the connection between present and past. This is true especially for the younger generations: their growing dependence on media has often deprived them of a proper historical perspective. The constant use of technology often tends to reduce their critical skills. Recent policies in the education field, both in the USA and in Italy, accentuated this problem by decreasing the role of Humanities in instruction.2,3

Education must focus on providing students with appropriate tools for a sustainable development. Sustainability education becomes crucial, because it trains students in a new way of looking at the environment.4 This approach involves understanding the natural and human history of the environment, to become aware of the connection between the two. This understanding leads to a better awareness of the preciousness of our planet and helps students to become better stewards of its future development.

Given this perspective, in Fall 2013 a group of undergraduate students at St. John International University used this approach to analyze the value of the Classical heritage reflected in the architecture of the university campus and surrounding areas.5 They discovered how much respect the ancient Romans and Greeks deserve, even though so often neglected. The research involved the Renaissance Della Rovere castle at Vinovo (Turin, Italy), where the campus was located, and the nearby centers of Vinovo and Piobesi (Figure 1).

The aim of the class was to develop students’ curiosity and to create a habit in their minds of looking at things with investigative eyes. My purpose was to make them aware of the beautiful location they had the chance to experience every day and to train them to become good stewards of such a precious heritage. To build a sustainable world, we are called “to interact with caution and respect” as Rachel Carson stated in her famous Silent Spring.6 The first step in this process is the awareness of history, which enables us to understand how art and architecture reflect the heritage of the past.

The awareness of history can also train new generations to deal with transformations especially in this age of accelerating change. During our research, we investigated several cases of innovations and the related reactions engendered through art history. Eventually, we discussed hypotheses for the future development of the castle and surrounding environment.

The students investigated several artworks which are still quite neglected by the current literature. Therefore, in addition to bibliographical research and on-site visits, the investigation included several discussions with members of the local association “Amici del Castello di Vinovo” who shared their knowledge and passion for this historic heritage with us.

The impact of classical culture in the renaissance period

The impact of the Classical culture was especially strong during the Italian Renaissance (14th-16th centuries) and Neoclassical period (18th-19th century). The Della Rovere castle, erected between the late 15th and the early 16th century, is therefore a perfect place to start this investigation and to understand the impact of the Classical culture on the Renaissance art.

The building was intended to be a new palace for the local, wealthy Della Rovere family, which included important members such as Pope Sixtus IV (Francesco Della Rovere) and the Cardinals Cristoforo and Domenico Della Rovere, Bishop of Turin.7 The castle was built on the remains of a preexisting medieval fortress, two towers of which were reused in the south-western façade.8 That side, facing the lovely park with its small lake, was the most important one in the past, while now the main entrance of the building is located on the opposite side, facing the town of Vinovo.

The plan (a square foundation with a tower on each corner and a central courtyard), the arrangement of the courtyard (Figure 2) and the north-eastern façade clearly reveal the Renaissance architectural style. From the 17th century the palace underwent several changes of ownership and consequential renovating phases, which altered its original Renaissance appearance.

Mauri D9 and Martinengo10 have provided a detailed study of the various steps of the history of the castle. After the Della Rovere family, owners of the castle were the Delle Lanze family (1680-1732), the Royal Savoy family (1732-1753) and the “Ordine Militare dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro”, usually known as “Ordine Mauriziano” (1753-1780). In 1776 King Vittorio Amedeo III granted the castle to Peter Anthony Hannong of Strasburg and Giovanni Vittorio Brodel from Turin to settle a factory producing porcelains. After his failure, Vittorio Amedeo Gioanetti established there a more famous porcelain factory (1780-1815). After Gioannetti’s death, Giovanni Stoppini in vain tried to revive the ceramic production (1824). The castle was then used by the Royal University of Turin as a summer campus for the students (1825-1836). The City of Turin gave the castle to the “Ospizio di Carità” (Poor House) which installed there a nursing home. The Rey brothers purchased the castle in 1843 and established a textile manufacture (1843-1918). In the late 1910s and again in the 1940s the castle was used by military corps. The Rey family inhabited the palace until 1965. The City of Vinovo owns the castle since 1973.

The original Renaissance appearance of the castle was partially brought to light by recent restoration works.11 Given the modern criteria adopted by the restoration, at first glance, students were already able to identify the difference between the original and restored portions of the structure. We therefore discussed the importance of the new regulations of the restorations, which prescribe that any integration must be easily identifiable and removable if necessary, in order to make the restorations sustainable.12

In the Renaissance, the Della Rovere castle was decorated with impressive frescoes which show a clear inspiration from the Classical world. Especially, a room on the first floor features a grotesque fresco stylistically close to the wall paintings of the Domus Aurea, residence of emperor Nero (AD 54-68) in Rome. The fresco in the main hall on the ground floor recalls the ancient Roman tradition too. Moreover, the terracotta decorations of the courtyard include portraits of Roman emperors and floral patterns directly inspired by Classical art.

Analysis of the courtyard of the della rovere castle

The most remarkable area of the castle is the central courtyard (Figure 2 no. 1).13 Every day the university community used to pass through the courtyard (Figure 3), but was perhaps too accustomed to its beauty to investigate its origins and meaning. The plan is slightly trapezoidal due to the presence of some preexisting architectural features. Four arches stand on the long sides and three on the short sides, supported by pillars located at slightly irregular distances, to create an illusion of regularity. Such a device was not an innovation introduced by Renaissance architects, since ancient Greek masons had adopted analogous refinements to solve architectural problems. An example would be the corner conflict of the Doric order, which resolved the spacing issues of design.

Pillars, arches and entablature are decorated with figured terracotta tiles. The focus of attention is surely a series of roundels depicting the portraits in profile of the Roman emperors Nero and Galba and a female figure. The last was identified as Libertas Restituta on the base of Roman coins depicting a personification of goddess Liberty.14 After Nero’s autocratic rule, indeed, Galba’s propaganda focused on the value of the “restored liberty” alluding to the improved cooperation between the Princeps and the Senate.15

Students analyzed the arrangement of the twenty-eight roundels and discovered that they follow a specific sequence which enhance this concept of resolution. Galba is depicted facing right, while Nero and the Libertas are facing left (Figure 4) (Figure 5). A pair of figures facing each other are located over each arch. Galba looks at Nero and is alternated with Galba viewing the Libertas Restituta. Only in the south-eastern side of the portico is this symmetry altered by the couple Galba-Nero repeated three times. This irregularity especially attracted the students’ curiosity. After discussing several explanations, we agreed that such an anomaly did not carry an intentional meaning, but is likely to have originated from a mistake. The hypothesis of a technical reason, such as for instance the number of roundels available, seems unlikely, given the local manufacture of the terracottas.

Another peculiarity attracted the students’ attention: the roundel in the western corner depicting Galba carries the incorrect legend NERO. The name of the emperor was likely inscribed after firing, given the irregularity of the incised letters (Figure 6).

In Renaissance Piedmont, the quotation of ancient emperors connected to important values such as freedom and justice was a usual subject in the decoration of private palaces belonging to wealthy families of jurists. During one of our fieldtrips in the close surroundings of Vinovo, we discovered a contemporary private building (Petitti palace) at Piobesi (Turin). The main façade features an analogous series of terracotta roundels.16 The series include ten portraits arranged in five pairs, with Galba facing the Libertas Restituta. Students noticed that Nero’s portrait is not included in this sequence (Figure 7).

In the courtyard of the Della Rovere castle, the terracotta decorations of the arches feature dolphins, oak leaves and acorns. The last ones are likely a direct quotation of the Della Rovere family, since the Italian word rovere means oak. The lesenes show an elegant vegetal decoration, developed on a vertical arrangement with symmetrical patterns, according to the Classical tradition. The cornice of the ground floor is inspired by the Classical motif of palmettes alternating with lotus flowers and is framed by astragals, according to a scheme which was well known in ancient Greek architecture.

The entablature was decorated with frescoes, removed in modern times for preservation reasons. These paintings depicted a Classical subject again: a marine thiasos (Dionysus’ retinue), with dolphins, tritons, sea monsters and musicians.17 We discussed in the class about the opportunity to restore the reproduction of the paintings to approximate the original. Our debate included obviously also the modern techniques of virtual restoration and its key role in sustainability.18

The fresco of the western hall (so-called Fresco Room)

The Renaissance fresco decorating the large western hall of the ground floor (Figure 2, no. 2) is clearly inspired by Classical art as well, both in subject and style. The frieze runs on the upper part of the four walls. It is arranged in a sequence of alternating sections with respectively red, brown and black background. Each section is delimited by a roundel on each end (Figure 8). The roundels portray famous figures of antiquity (Tarquin the Proud and Lucretia, Antoninus Pius and Faustina, Brutus and Portia and so on).19 Pairs of tritons hold the roundels with one hand and a horn of plenty in the other one. Cupids ride the tritons’ tails and hold oak branches which again allude to the name of the Della Rovere family.20 As a symbol of rebirth, a phoenix rises from the fire of a lighted brazier located between the wings of the opposite cupids. In addition to the direct quotation of famous ancient figures, there are many references to the Classical world: cupids, tritons, horns of plenty and the phoenix.

The grotesque fresco of the first floor

The most typical example of direct influence of antiquity in the Renaissance period is the use of grotesque paintings. This style spread through Italy in the 15th century, after the fortuitous discovery of the remains of the Domus Aurea (Golden House), which had been buried by the Flavians in the second half of the 1st century AD. The grotesque style was very successful also in Piedmont especially in the 16th century. Examples of grotesque frescoes are for instance seen at Manta, Lagnasco, Ceva, Fossano, Biella, Ozegna and Vinovo.21

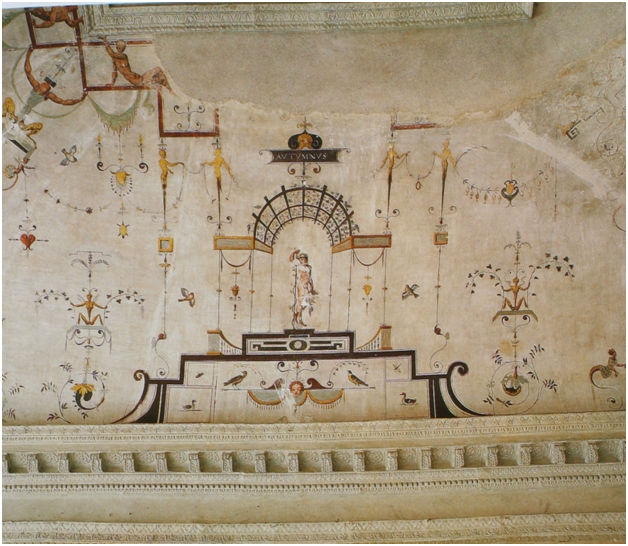

A grotesque fresco decorates the ceiling of the room on the first floor of the southern tower of the Della Rovere castle (Figure 9). It was likely painted around 1570 by an artist from Piedmont.22 The chamber is called “Room of the Seasons” after the subject depicted.23 The painting features the four seasons portrayed as deities, standing on pedestals below a bower. According to the ancient Roman technique, elegant vegetal, figured and fantastic motifs stand out from the homogeneous white background, arranged in a symmetrical composition. Graceful decorative elements enrich the scene: birds, masks, volutes, candelabra and florals. Style, composition and decorative patterns are particularly close to the frescoes of Nero’s Golden House itself (Figure 10).

It is quite interesting to compare the reaction of the art critics to the fantasy of the grotesque style both in the Roman age and in the Renaissance period. According to Vitruvius in his De Architectura (1st century BC)6 and to Giorgio Vasari in his Lives (16th century), the fantastic motifs of the grotesque style were “monsters”, because they seemed illogical and unrealistic.24 This provides a fine example of how emulation affects style across time and shows the negative reaction towards innovation throughout history. To learn how to cope with change and innovation is another prominent issue on which sustainability education must focus.

The impact of classical culture in the neoclassical period

The revival of antiquity became very successful again in the Neoclassical period. A good example is present in the city center of Vinovo. It is an impressive building, known as Vigliani palace, erected in the mid-19th century (Figure 11).25,26 The elaborated brick façade reveals the source of the owners’ wealth: a factory producing bricks, located along the ancient road to Candiolo (Turin). After a detailed investigation of the façade, students could distinguish several elements directly inspired by the Greek and Roman architecture, such as the triglyphs derived from the Doric frieze, the dentils and astragals inspired by the Ionian architecture, and the elaborate capitals recalling the Corinthian order. They easily understood the difference in the use of such features between the modern and ancient architecture.

The study faces several aspects of sustainability education, by treating the case study of the influence played by antiquity on modern art, based on the examples provided by a peripheral reality, located in Piedmont (northern Italy). The reception of Greek and Roman culture in fact played a key role on the development of the arts in western society. This process was especially strong during the Renaissance and Neoclassical periods. While major evidence is well known on a global scale, the local effects on a small village in northern Italy (Vinovo, near Turin) were investigated by a group of undergraduate students from St. John International University. They discovered the ancient origins of several features adopted in Italian architecture during the Renaissance and Neoclassical period. By thinking at a global level, but acting at a local scale, they learned how important the cultural heritage is in our lives. They analyzed the risks which still jeopardize the historical artefacts and managed to find sustainable solutions to preserve the cultural heritage. Through their education for a sustainable development, they learned how to investigate the history of the environment and to become empowered and responsible citizens.

I wish to acknowledge the students who took part in this project for their enthusiastic participation.5 I am also pleased to thank prof. Thomas Leach (St. John International University) for proof-reading my text and for enjoying with me lovely discussions on the fascinating matter of sustainability education.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2017 Catti. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.