Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Conceptual Paper Volume 5 Issue 2

1Department of History, Faculty of Human Sciences, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia

1Department of History, Faculty of Human Sciences, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia

Correspondence: Adnan Jusoh, Department of History, Faculty of Human Sciences, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 39500 Tanjung Malim, Perak, Malaysia, Tel +601033981004, Fax +6054598606

Received: January 28, 2020 | Published: March 12, 2020

Citation: Jusoh A. A study of dotaku bell (Japan) and bronze bell (Malaysia) from an archaeological and sociocultural perspective. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2020;5(2):46-52. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2020.05.00216

This article focuses on the discovery of a type of artefact in the Asian continent; namely the dotaku bell (Japan) and the bronze bell (Malaysia). Bronze bells have distinctive designs and unique decorative patterns, and their distribution has raised questions in terms of their function, origin, form of dissemination and use in their practitioners' community. This article discusses the discovery of two specific types of bronze bells, particularly in terms of the similarities and differences in their design, function, decorative pattern and origin. We applied the library method, examining information from books, articles, research reports and sample research at the Department of Museums Malaysia, the Shah Alam Museum Board (Selangor) and the Shiga Prefectural Azuchi Castle Archaeological Museum, Japan. The findings show that dotaku bell was related to the Yayoi period, while the bronze bell from Malaysia represented the Iron Age artefacts. There were significant differences between these bronze bells, especially in terms of their shapes and decorative patterns. These differences are manifestations of the life of people from those times, who were adapted to their environment. These adaptations took into account geographical aspects, sources of raw materials, technology, sociocultural life and so on. These two objects indirectly help us understand the development and lifestyle of their practitioner communities in several locations in Asia. This knowledge can be understood through the sketches of decorative motifs in the form of animals, geometric, abstracts and so on.

Keywords: Dotaku bell, bronze bell, archaeology, artefacts, sociocultural

The geographical area of Asia is extremely extensive, comprising highlands, deltas and lowlands. Seas, rivers, lakes, swamps, hills and mountains often served as a dividing point between the various ethnic groups and tribes that inhabited these continental landscapes. The ethnic groups scattered all across the Asian continent eventually formed their own identities. Ethnic groups often try to maintain their sociocultural wholeness, but may also be affected by external influences and elements. Slowly, their sociocultural dimensions were also affected, resulting in a unique and interesting heritage. From prehistoric to modern times, the Asian continent has been a landscape of human life, of many different varieties and challenges. Various ethnic groups have inhabited all parts of the continent by adapting to the advantages of their environment and its natural resources. It was also where many religions and beliefs began, including animism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity, and so it had strong sociocultural influence. Material culture was shared from local groups to other ethnic groups, suggesting values of togetherness and a sense of belonging.

Various artefacts have been produced from prehistoric and protohistoric times, such as pottery, stone tools, ornaments, object for rituals or funerals, weapons, temples, statues and so on. These objects were made of soil, stone, metal, iron, tin or the like, and have been found at several archaeological sites throughout Asia. Some of these monuments also have become benchmarks in our efforts to assess the level of ability and achievement of the people who produced them. For example, Borobudur, Prambanan and Mendut Temple in Indonesia; Angkor Wat, Angkor Thorm, Angkor Borei and Bayon Temple in Cambodia, are all manifestations of intellectual achievement and civilization in ancient times. Many artefacts produced by this ancient society can be seen today, either in exhibition galleries or museums. The focus of this paper is two types of bronze bells, found in Malaysia and Japan.

Background

Japan and Malaysia are both countries in Asia, but Japan is located in the northeast and Malaysia in the southeast of the continent. They are distinguished by different climates and population demographics, and many other features, including sociological aspects such as language, writing, beliefs, ways of life, traditional practice and so on. There is a huge gap in the scientific and technological achievements of the two countries. The discovery of several types of archaeological artefacts in both countries suggests that certain aspects of human achievement go hand in hand, particularly in a certain period of time. Bronze drums and bronze bells are both found in the Iron Age in mainland Asia. Both objects have similarities in terms of external decorative motifs that make them distinctive, however, when carefully examined; the design and style of these decorative motifs are very different. Despite the fact that both were made using several metal components, there are also significant differences between the bronze bell and the bronze drum in terms of the design and size.

Bronze bells have been found in several locations across Asia, and their design and physical structure varies. These objects have been given several names, some related to the location in which they were found. Terms used for these objects include bronze bell (Cambodia), Dongson bell (Malaysia), Sheep horn bell (China) and dotaku bell (Japan). Most bronze bells found in the Asian region are believed to have been made during the Iron Age, at the end of the Neolithic Age around 500 BC. These objects are so distinctive that they have been widely studied by many researchers. This paper focuses only on the dotaku bell (Japan) and the bronze bell (Malaysia), and discussion focuses on the history of their discovery and their significance to the local community.

Dotaku bell have been studied by researchers from Japan and the West. Harunari Hideji is a Japanese researcher who is famous for writing about the dotaku bell. He wrote three (3) articles about the dotaku bell: ‘The age of the dotaku’ (Vol. 1),1 ‘Rituals involving dotaku bronze bells’ (Vol. 12)2 and ‘The interpretation of a drawing of a fight sketched on a dotaku’ (Vol. 25)3 published in the Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History series. In general, Harunari Hideji's writings are focused on his studies in the field and are widely referred to by other scholars, as his writings are detailed and comprehensive. Yoshiro Kondo also touched on the dotaku bell in ‘The development of Yayoi culture and associated changes in social relations’ published in the Japanese journal Nihon no kokogaru, in 1966. Yoshiro Kondo's writing shows the relationship between people in the Yayoi period and the development of material culture.4 In 1970, Makoto Sahara wrote about his findings in ‘The Tamato River and the Yoru River’, published in Kodai no Nihon nook bunka ni seisei. Makoto Sahara focuses on the role of the river in human settlements and the development of society, based on the discovery of the dotaku bell and other artefacts.5 In 2009 Leo Aoi Hosoya wrote an article about the dotaku entitled ‘Sacred commonness: An archaeobotanical approach to Yayoi social stratification: The Central building model and the Osaka Ikegami Sone Site’, published in Senri Ethnological Studies.6 In 1992, Mark J. Hudson wrote an article entitled ‘Rice, bronze and chieftains-an archeology of Yayoi ritual’ published in the Japanese Journal of Regional studies. His writing shows the relationships between agricultural activities, rituals and the role of tribal leaders in the life of the Yayoi people in Japan.7 A relatively recent article on the dotaku was written by Reinier H Hesselink8 in 2016, entitled ‘The Dojoji tale and ancient bronze metallurgical traditions’ published in the journal Comparative Mythology, Vol. 2 (1).8 This paper also discusses the development of material culture based on metal equipment and its importance to the practitioner community during the Yayoi period in Japan.8

On the whole, it can be said that most of the articles related to the dotaku bell by Japanese and Western scholars were written in a detailed and scientific way. The large number of dotaku bell found in Japan allowed researchers to undertake more comprehensive research. Some of the writings were also based on archaeological excavations at several archaeological sites in Japan. A slight problem is that most reports or articles about the dotaku bell are written in Japanese. This has affected the dissemination of information, compared to articles written in English. The bronze bells in Malaysia have been discussed by several scholars; however, these articles tend to lack detail, probably due to a lack of resources. Compared to the more popular bronze drums that are frequently discussed by researchers, the bronze bells tend to be only briefly discussed. The number of bronze bells in Malaysia is also relatively small compared to bronze drums. Information on the discovery of the bronze bells is also incomplete because most findings were accidental (chance finds). This has resulted in a lack of articles on the bronze bells. Researchers who have written on the bronze bells in Malaysia, include Linehan,9 Bellwood,10 Rahman11 and Jusoh.12

Linehan was a colonial researcher in the 1950s who wrote about the bronze bell in Malaysia. His paper was published in JMBRAS, issue 6, 1993, and entitled ‘Traces of a Bronze Age culture associated with Iron Age implements in the regions of Klang and the Tembeling, Malaya’. Although the scope and focus of his research involved the finding of several bronze artefacts, including bronze drums, beads and pottery found in Klang, Selangor and Sungai Tembeling, Pahang, his writing also reports on bronze bells. Linehan9 reports an analysis of metal content in the bronze drums found in ‘Sungai Tembeling, Pahang and the bronze bells found in Kelang, Selangor’. The data presented included the metal content percentages, comprising copper, tin, iron, lead, zinc, carbon, silicon, phosphorus, manganese and many others in the artefacts. Linehan9 showed that copper was the major metal element in the manufacture of the Klang's (Selangor) bronze bell at 78.5%, followed by 15.1% tin and 2.9% lead. Bernet Kempers also reported on the discovery of bronze bells in the Malay Peninsula: three bronze bells in Klang, Selangor that featured motifs in the form of spirals and sawtooth motifs.13 He only reported the findings briefly, however, and gave them no special emphasis.

Rahman wrote about the discovery of several bronze bells in Southeast Asia, in a book that he edited entitled ‘Early History’, Vol. 4, published by Archipelago Press, Singapore, in 1998. He stated that four (4) bronze bells had been found in Malaysia and one in Cambodia. There were four (4) bronze bells found in total, three (3) of which were reported to have been found in Kelang (Selangor), and another in Muar (Johor). Rahman14 also discusses the discovery of these artefacts in Malaysia, and relates it to the discovery of a bronze bell in Cambodia. There are significant similarities in terms of physical appearance as well as the decorative patterns displayed on the bronze bells found in Cambodia or Malaysia. Rahman did not rule out the possibility that the discovery of the bronze bells was a manifestation of a relationship between the two countries, especially in terms of trade. It is possible that the spread of bronze bells to Malaya had something to do with the Funan government.

Rahman15 also wrote about the discovery of a bronze bell in Kampung Penchu, Muar, Johor. The article is entitled ‘Loceng gangsa, Penchu, Muar, Johor, dalam konteks Zaman Gangsa Malaysia’, issued in Jurnal Warisan Johor and published in 2000. He noted that in 1963 another bronze bell had been found in Kampung Penchu, Grisek, Muar, Johor, about 500 meters off the banks of Sungai Penchu, a tributary of Sungai Muar, Johor. It was discovered by accident when villagers were levelling the land. The bronze bell measured about 58 cm in height and 32 cm in diameter.15 This bronze bell was found at a depth of one (1) meter. According to Rahman, the shape of the bronze bell resembled those bronze bells found in Klang (Selangor) and Battambang (Cambodia). The bronze bell at Kampung Penchu, Muar, suggests the existence of trade activities, especially towards the end of prehistoric times, and the possibility that its dissemination in Peninsular Malaysia was related to the Laluan Penarikan (Penarikan Route) and the location of raw materials (mainly tin) on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula (Lembah Kelang, Selangor) was not ruled out.15

Rahman14 also associates the presence of the bronze drums and bells with beads imported from India and locally made pottery, showing how well the trade relationship developed between the community and the areas outside the Straits of Malacca. He stresses that the presence of the bronze drums and bells in the coastal areas of the Straits of Malacca could not be attributed to Deutro-Malay arrivals, but that the discovery had something to do with the source of the tin ore resources needed for the manufacture of bronze objects in Vietnam. The need for tin ore had led to the existence of a relationship between the locals and outsiders, thus establishing settlements in the Straits of Malacca such as Kampung Sungai Lang (Selangor), Kampung Penchu (Johor) and Kuala Selinsing (Perak). Eventually, progress in maritime trade in the Iron Age succeeded in bringing about the socioeconomic development of the coastal communities of the Straits of Malacca. There were a number of important ports, including Takuapa, Kedah, Palembang and Jambi, in the 5th century AD.14

Jusoh published an article related to bronze bells in Malaysia entitled ‘Loceng gangsa purba di Malaysia: Sumbangannya dalam penyelidikan peradaban masyarakat peribumi purba’, in the Jurnal Melayu, Volume (5), 2010, featuring the history of the discovery of bronze bells in Peninsular Malaysia.16 The focus of the discussion was on the benefits of the discovery of these objects, and considered the motifs and decorative patterns displayed on the bronze bells, comparing them with the bronze drums found in Malaya. A study was also conducted to look at the metal content in the bronze bells of Klang, Selangor. His other publication on bronze bells is ‘Loceng gangsa di Asia Tenggara dan kepentingannya dalam konteks arkeologi’, presented at the 3rd International Seminar Archaeology, History and Culture in the Malay World (ASBAM3), held on 23-24 December 2014. This paper discusses the classification and origin of the bronze bells found in Southeast Asia.17

Dotaku bell (Japan)

The shape of the dotaku bell in Japan is very different than that of the bronze bells found in Malaysia. This type of bell is found widely in Japan, and also Korea and China. The dotaku bell is believed to date from the end of the early Yayoi period to the late Yayoi period. Before discussing the dotaku bell, it is important for us to first understand the system of dating used in Japan. The terminology used by Japanese scholars is slightly different when it comes to the system of dating, especially in relation to their archaeology and history (Figure 1). As seen in Figure 1 the Yayoi era is a post-Jomon period, associated with the prehistoric ages in Asia, and can be attributed to the Iron Age. The dotaku bell was produced in the Yayoi era, which is part of the Iron Age in Asia (Figure 2).12

Dotaku bell were sometimes found in small numbers in Japan, but it has also been found in large groups. For example, in Sakuragaoka, in the Hyogo Prefecture area, 14 bronze bells and 7 bronze halberds were found. Some of these objects are believed to have been used for ritual activities. Most of these dotaku were produced by the ancient society, especially during the Yayoi phase VI, and were found in the northern area of Kyushu up to central Honshu. This type of bell was widely used in almost all regions during that time.18 As of 1985, more than 400 dotaku had been found, mainly in southwestern Japan. The number of dotaku discovered has been steadily increasing over time. For example, Hudson notes: As of January 1992 there were 430 dotaku known from 302 sites. Fifteen bell fragments and the 62 dotaku whose provenance is unknown should be added to these to give a grand total of 507. At present, the whereabouts of 112 of these bells are unknown. Most of the bells were found buried on isolated hillsides away from settlements, and there can be no doubt that they were buried there intentionally.7

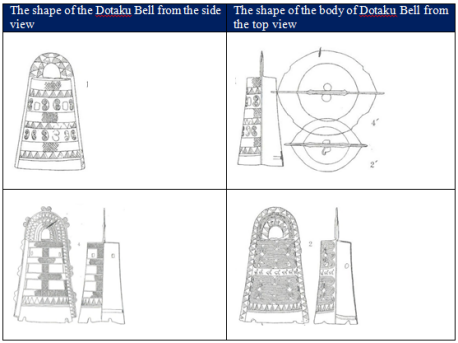

The main feature of dotaku is its cylindrical body structure, which widens towards the bottom. The dotaku bell is distinguished from the bronze bells found in Malaysia by its head, which is shaped like a thin sheet that curves from the side (the bronze bell's waist) going up and back down to the side (waist) of the bronze bell. The thin sheet seemingly acts as a handle because it has a hole at the top of the bell's body. The handle (thin sheets) sometimes has a decoration the size of a 10 cent or 20 cent coin. There are also bronze bells of this type that do not attach any decorative pattern that highlights the thin round handle. The handle sheet is also often decorated with either one or two curve-shaped spines in the shape of the handle (Figure 3). There are a number of rings around the body of a dotaku bell. Scratches on the spine of the bronze bells are placed in a vertical position in such a way that they form a square edge when intersecting with the vertical spines. The middle of the spine usually includes a variety of decorative motifs. Some of the most common decorative motifs are deer, fish, wild boar, herons, lizards, spiders, snakes and turtles (Figure 4). Some dotaku are decorated with geometric motif displays, but some also feature animal motifs such as deer, and aquatic animals (crab, turtle, frog and snake). There are also motifs and decorative patterns on the body of dotaku that resemble human figures carrying out activities, including hunting, fishing and harvesting (Figure 5). There is sometimes a small hole on the body of a dotaku bell, especially at the top (usually 4 holes). Similarly, there is sometimes a small hole at the foot of the dotaku, based on the size of the bell. The actual function of this small hole is unknown, but it is likely to be involved with producing the ringing sound. The foot part (bottom) of the bell is not round in shape, but slightly elongated. The following diagram shows the structure of a dotaku from different angles (Figure 6).

Figure 6 The shape of Dotaku Bell (Japan) in defferent angles.

Sources: Training course of cultural heritage protection in the Asia-Pacific Region, 2006.

Bronze bell (Malaysia)

Bronze bells in Malaysia are sometimes referred to as Dongson bells, although technically this name needs refinement. Bronze bells became better known when they were announced as one of the objects classified as National Heritage under the National Heritage Act 2005 in 2009. The existence of bronze bells in Malaysia must be looked at chronologically. The position of the Iron Age is shown in Figure 7. Four (4) bronze bells have reportedly been found in Malaysia to date. According to Rahman,11 three (3) of these were found in Klang (Selangor), and another in Muar (Johor). These bronze bells were almost identical in features, as if they had originated from the same location (Table 1). The physical shape of these bronze bells comprises two main components, the head and the body. The head is the top most part, and is delineated from the body by a curve; it then widens downward to its cylindrical body. The head is smaller than the bronze bell's body. This type of bronze bell also has no handle, and was probably carried using the curved area located between the head and the body of the bell. The body of the bronze bell is usually illustrated with motifs and decorative patterns.17 The general physical structure of a bronze bell is as follows; This type of bronze bells (Malaysia) are relatively thin. This bell's motif shows an S-curve decorative motif sketched repetitively on the body. A "langgam" a curve that almost resembles the letter ‘S’, is located in a rectangular motif and is repeated until it covers the whole body of the bell (Figure 8). There is no definitive interpretation of the symbol or motif to date. This S-shaped motif may represent a river flowing from upstream to the downstream. Rivers have been important to the lives of people in the past, as sources of clean water, sources of income and sources of agricultural activities, settlement patterns, and communication systems and so on (Figure 9).

Location |

Total |

|

1 |

Klang, Selangor |

3 (Three) |

2 |

Kg. Penchu, Muar, Johor |

1 (One) |

Table 1 The findings of the bronze bell in Malaysia

Comparison between the characteristics of dotaku bell (Japan) and bronze bell (Malaysia)

Dotaku bell in the early phase have thick shells, but in terms of physical structure, are relatively small in size. The physical structure of dotaku bell in the later phase is larger, but a little thinner compared to the earlier forms. The structure or shape of the handle used to hang the body of the dotaku bell is thin and flat. The metal composition of the dotaku is 87.29% copper, 5.6% lead and 4.31% tin (Tanabe Ikuo). Table 2 compares the decorative motifs displayed on the body of the bronze bells found in Asia so far. The bronze bells found in Peninsular Malaysia are typical in terms of its S-curve or river flow pattern. This pattern is displayed on almost the entire body of the bell (Jusoh, 2014). These motifs were also found on several dotaku bell (Japan) bells. Most of the dotaku bell found in Japan, however, displays animal motifs of various types, including animals that live in forests, the sea or mangrove swamps (Figure 10).

Bell classification |

Motifs |

|

1 |

Dotaku Bell (Japan) |

·Animal motifs such as deer, pigs, snakes, turtles, dragons, lizards, spiders and fish. |

·There is also a curved line motif in the form of the letter S or resembling a river stream. |

||

2 |

Bronze Bell (Malaysia) |

·Curved line in the form of the letter ‘S’ or resembling a river stream. |

Table 2 The classification and motifs of dotaku bell (Japan) and bronze bell (Malaysia)

Significance from an archaeological perspective

The discovery of bronze bells has opened a new chapter in our efforts to understand the phenomenon of post-Iron Age society. By examining the motifs and decorative patterns displayed on the bronze bell, we can learn more about society at that time.

The origin

The exact origin of the bronze bell is quite difficult to determine as there is no written record available, but according to the findings so far, it is definitely in Asia. The number of discoveries is quite small compared to those of bronze drums. The number of bronze bell discoveries in Asia is also rather uneven. The number of bronze bells found in Malaysia is small, but they have their own significance. Dotaku bell are found in Japan, Korea and China. Dotaku bell are believed to originate in Korea. This is in line with Hudson's opinion: The two most characteristic Yayoi bronze implements were bells (dotaku) and weapon. Both of these were initially imported from the continent, but soon thereafter were produced in Japan.7 The bronze bells found in Malaysia seem to have originated in Cambodia. Funan in Cambodia was the early kingdoms from the 2nd century AD to the 6th century AD. The Funan government was the dominant force. The Sriwijaya kingdom emerged in the Malay-Archipelago Islands, from the 7th to the 11th century, after the collapse of the Funan kingdom. As explained earlier, the bronze bell was believed to have been invented around 150 AD. This means that it was created during the time of the Funan kingdom in the region. The Funan kingdom conquered almost all the early kingdoms on the mainland of Southeast Asia and became a powerful maritime power. The similarities between the bronze bells in Malaysia and those in Cambodia suggest that the Malay Peninsula may have been ruled under the Funan kingdom. Another possibility is that there was a trade relationship between the Malay World and the Funan kingdom which allowed the bronze bells to be spread into the Malay world. The identical nature of their overall physical shape, the motif sketches and decorative patterns of the four ancient bronze bells found in Malaysia mean that it is very likely that the bronze bells came from the same place and period. This is in line with Rahman's11 summary which suggests that the similarity of the design, shape and size of these bells shows that they originated from the same place. In this context, the origins of the dotaku bell (Japan) and the bronze bell (Malaysia) seem unrelated, however, in the macro context, both are from mainland Asia, and are probably from the same source. The different shapes may be due to the innovation and creativity of the local community, but basically, they share a similar concept regarding view of life.

Economic activities

Several types of motifs displayed on the bodies of the bronze bells suggest that agriculture was an important socioeconomic activity. Dotaku bell also feature animal motifs such as deer, wild boar, snakes, turtles, and so on. The animal motifs indirectly strengthen the association with people living in rural areas at that time. These animals may have been hunted for the survival of the people at that time. Another possibility is that the animals are representative of the environment or the surrounding areas of the community settlements, near the forest, mangroves or coast area. None of the motifs found on the bronze bell (Malaysia) can be associated with agricultural activities. The S-shaped curve motif resembles a river flow, and may suggests the importance of the river as one of the major modes of transportation in the life of the people at that time, as well as in providing a source of protein. The river flow motif can also be found on some of dotaku bell. This phenomenon suggests the importance of rivers in the Malay World is similar to that in the Japanese Yayoi period, whether as a source of water, for agricultural activities, systems of communication or transportation. The economies of the Japan and Malay worlds at that time were based on agricultural activity. The motifs of deer, wild boar, snakes, turtles, and so on, are in line with the way of life of humans living near a forest, mangrove, lake, river or beach. These animals were a source of protein hunted by the nearby community for survival.

The function

One of the original purposes of a bell is to obtain a sound when hit with either a stick or a clapper. The motifs and decorative patterns displayed on the body of the bells allow scholars to study them more comprehensively. Several interpretations have been offered, particularly to understand the lifestyle of the people of that time. The motifs of the dotaku bell indirectly allow us to better understand sociocultural aspects of the communities that lived during the Yayoi period in Japan.

Ritual

Many Japanese scholars associate the motifs and patterns of the dotaku bell with ritual activities. Various rituals were practiced by the Japanese people at that time, including burial rituals and the worship of the spirits of deceased ancestors. Some scholars believe that the dotaku bell is planted in the ground, but it will be taken back for use especially during certain festive events.5 For example, Makoto Sahara suggests that dotaku were kept buried in the soil in normal times and only brought out for special festivals. Dotaku bell are believed to have mystical power, and to be used for ritual ceremonies related to the worship of the spirit or soul. According to Mishina:19 ….the dotaku was buried in order to accumulate the spirits of the earth who promoted crop growth; therefore, the process of uncovering the dotaku represented the carrying of the spirit to the community.9

The motif display may also suggest that the dotaku bell were used in rituals related to activities such as harvesting crops. According to Harunari: The bronze bell was a magical vessel that confined grain spirits within the unhulled rice, that guarded them from other earthly spirits such as drought, heavy rain, and wind. Therefore, the place where the bronze bell was stored was the same place where grain spirits were stored. When grain spirits dwelled in the rice paddies after the sowing [and] before the harvest, the bells might have been kept in the storehouse and taken out to ring when necessary.

Burial

The importance of the dotaku bell may have involved the responsibility of the leader to organize a ritual ceremony. The leader represents their community in dealing with a spirit or soul during a ritual event. For example, the leader may convey to a soul or spirit the desire of their community to be given fertile land, to avoid the threat of an enemy, increase agricultural produce, ensure the safety of the community and so on Kondo:4 At the same time, it is thought that a community leader was responsible for organizing the dotaku ritual, given that this community-based activity required a representative leader..…. Accordingly, the leader may have become the symbol of the community being invested with the ability to mediate between the Spirit of the Crops and the people to ensure the maintenance of agricultural production.6

The dotaku bell (Japan) and the bronze bell (Malaysia) in Asia emerged from the same period, the Iron age. Materially, both types of objects were made of several kinds of metal components, resulting in their endurance to this day. The physical shape and the decorative patterns of these two objects are significantly different, due to different raw material supplies, the innovation elements and the creativity of the maker. One important thing to acknowledge is that the existence of these objects is closely related to the activities and sociocultural lives of the practicing community of their time, as demonstrated by the motifs and decorative patterns displayed on the objects.20−23

This research was carried out with the assistance of The Sumitomo Foundation, Japan. The authors wish to express their gratitude to The Sumitomo Foundation who provided the research fund and the parties involved in this research (Research Code-2019-0107-108-11).

My research project was partially or fully sponsored by (The Sumitomo Foundation) with grant number (2019-0107-108-11).

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2020 Jusoh. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.