Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

The article describes the early Middle Age horse skeletal remains yielded by the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites from Eastern Ukraine. According to the obtained results, the Saltovo-Mayaki domestic breed represents an improved riding horse with the medium height at the withers, thin and semi-thin metacarpals, elongated phalanxes, moderately short muzzle, relatively large cheek teeth and long protocone in upper cheek teeth. A large number of juveniles and few seniles in the studied sample suggest that Saltovo-Mayaki Culture bearers practised hippophagy. This conclusion is supported by the recorded cutting tool marks on horse bones.

Keywords: early middle age, saltovo-mayaki culture, horse, morphology, hippophagy

L, length; DLM, lateromedial diameter or measurement; DAP anteroposterior diameter or measurement; ANT, anterior; POST, posterior; DIAPH, diaphysis

The Medieval polyethnic bearers of the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture from the Seversky Donets area (Kharkiv and Lugansk Provinces, Ukraine) were closely associated with the Khazar Khaganate and left a large number of archaeological monuments in the Pontic steppe region and adjacent steppe-forest area roughly between the Don and the Dnieper Rivers. The 10th century is regarded as the upper chronological border of the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture (or Saltov Culture), while the archaeological sites from the Seversky Donets area included in the present study are dated back to 9th century.1−3 Various variants of the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture represent specific stages of social-economic transition from nomadism to semi-sedentary agropastoralism.4 Horses remained an important domestic animal in the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture and represented a direct link between the nomadic past and the socio-economic relationships within the groups of Saltovo-Mayaki Culture bearers.5,6 The horse in the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture was not only an important source of food, draft force and transport mean, but also was considered sacred and sacrificial animal.6 Nonetheless, Khazar horses are still very little known despite the rich archaeozoological material yielded by the Saltovo-Mayaki sites, while the published characteristics of the Khazar horse breeds are incomplete and contradictory. Matolcsy5 reported the horses from the Mayaki Site as animals with the low (134.2cm) and medium (134.0-141.8cm) height at the withers. Pletniova’s7 analysis of Saltovo-Mayaki horse images suggest the presence of two distinct horse breeds: a long-limbed breed with small heads and a robust short-limbed breed with relatively short limbs. Our results of a preliminary study of horse remains from Saltovo-Mayaki sites of Eastern Ukraine suggests that the horse long limb bones are quite uniform and belong to a large improved horse breed with thin metapodia and first phalanxes and massive strong second phalanges.8

The present study aim is a detailed morphological, taphonomic, and demographic analysis of horse remains from the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites of Eastern Ukraine and the comparative characteristic of the Saltovo-Mayaki horse breed and the use of horse by the Saltovo-Mayaki Culture bearers. The archaeozoological assemblages from the Saltovo-Mayaki sites in most cases are dominated by cattle (from 48.2% of the total number of individuals of domestic animals in the Mohnach Site to 17.6% in the Mayaki Site); small cattle (48.8-18.5%) and domestic pig (33.9-6.8%) remain an important source of meat.8−10 The structure of the Saltovo-Mayaki domestic animal assemblage suggests a rather strong dependence of water sources (cattle) and a rather sedentary farming (important presence of pig remains). Nonetheless, the horse remains are still quite numerous on Saltovo-Mayaki sites and vary from 12% of the total number of domestic animal individuals in Mayaki to 32.5% at Karhauhovo.8

The archaeozoological material comes mostly from the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites situated in the valley of Seversky Donets River on the territory of Kharkiv Province, with exception of Faschevka site situated on the territory of Lugansk Province, Ukraine (Figure 1). The archaeological excavations were carried out by the research team of the Kharkiv National Pedagogic University under the direction of Prof. Vladimir Koloda.11−13 The part of archaeozoological horse remains (including the horse skull, phalanxes, and long limb bones) are stored in the Institute of Zoology (Chisinau, Moldova).

Figure 1 The Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites studied and discussed in the present study: (1) Mayaki. (2) Volchansk. (3) Upper Saltov. (4) Piatnitskoe 1. (5) Mohnach. (6) Korobovy Hutora. (7) Roganina. (8) Faschevka.

The measurements of cranial and postcranial material are taken according to Gromova14,15 and Kuzmina.16 The body mass estimation is based on craniodental variables according to the methodology proposed by Janis.17 The height at the withers is estimated according to Vitt.18 The classification of horse limb robustness is adapted from Brauner.19 All measurements are given in millimeters, with exception of heights at the withers, which is indicated in centimeters. The age structure of horse remains is based on the record of an individual ontogenetic stage of dentition development: individuals with milk teeth are reported as "juveniles"; individuals with deeply worn teeth are reported as "seniles", while the individuals with fully developed functioning dentition are reported as "adults".

The following samples are included in the comparative analysis

Skull

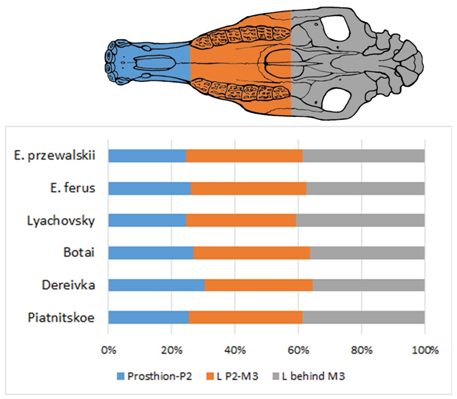

The skull of the young male from Piantitskoe-1 is well preserved and just damaged in the anteorbital area, therefore the distance between orbit and the prosthion point was unavailable for measuring. The skull belongs to a rather large young adult male. The size of the skull from Piatnitskoe-1 exceeds the mean values of the cranial series of coeval domestic horses from Rurik Hillfort (Northwestern Russia) (Tables 1 & Table 2) and rivals the largest skulls of the sample. The skull is characterized by a relatively short muzzle, which is significantly shorter than in the horse from Dereivka, and somewhat shorter than in the horses from Botai (Table 1) (Figure 2). The skull is relatively broader at the posterior edges of orbits: this measurement attains 43.6% of the basal length in the skull from Piatnitskoe and this value is quite close to that of the sample from Botai (44.2%). The skull from Dereivka is somewhat narrower (43.0%), apparently, because of its relatively long muzzle. Wild horses involved in the comparison (“Shatilov’s tarpan”, Equus przewalskii, and Equus sp. from Liakhovsky Island) are characterized by the relatively narrower skulls (the frontal breadth to basal length ratio amounts to 42.9% in all three cases).

Measurement |

Piatnitskoe-1 |

Dereivka (nr. 44-1192) |

Botai * |

Rurik Hillfort* |

E. ferus (ZIN-521) |

E. ferus uralensis |

E. ferus ssp. (Lyakhovsky Islands) |

E. przewalskii * |

Condylobasal length |

513 |

543 |

||||||

Basal length |

486 |

500 |

490 |

479.4 |

468 |

517 |

501 |

481.5 |

Premolar-basal length |

363 |

353.1 |

351 |

378 |

||||

Distance between opisthocranion and prosthion |

545 |

546 |

520.4 |

520 |

||||

Distance between prosthion and P2 |

123 |

152 |

128.2 |

121 |

122 |

118 |

||

Distance between prosthion and orbit |

335 |

308.9 |

303 |

320 |

321 |

|||

Upper cheek tooth row length (P2-M3) |

175 |

170 |

180.8 |

164 |

171 |

175.5 |

174 |

177.7 |

Upper premolar series length (P2-P4) |

93 |

89.7 |

||||||

Upper molar series length (M1-M3) |

80.4 |

77.3 |

||||||

Length of diastema |

90.2 |

108 |

96.7 |

95.8 |

84 |

103 |

87.8 |

|

Palatal length |

266 |

270 |

267 |

255 |

266 |

262.7 |

||

Length of nasal bones |

193 |

220 |

239 |

|||||

Breadth of nasal bones |

113.7 |

120 |

108 |

|||||

Breadth of upper incisors |

70.7 |

76 |

73.3 |

67.3 |

67 |

72 |

70.2 |

|

Maximum breadth of skull (behind orbits) |

212 |

215 |

216.7 |

201.6 |

201 |

214 |

215 |

206.6 |

Length P2 – occipital condyles |

388 |

|||||||

Height of occiput |

100.1 |

88.5 |

88 |

102 |

||||

Breadth of occiput |

121.6 |

|||||||

Breadth of condyles |

87.1 |

78.3 |

Table 1 Cranial measurements of ancient domestic and wild horses. The data on presumably domestic horses from Botai (Kazakhstan) and wild E. przewalskii and E. ferus uralensis (Late Pleistocene, Urals);16 the data on Late Pleistocene horse from Lyakhovsky Island are adapted from Gromova;14 the measurements of the Iron Age horse from Dereivka (Ukraine) are adapted from Bibikova;25 data on Medieval domestic horses from Rurik Hillfort (Northwestern Russia) are adapted from Spasskaya et al.16 The asterisk (*) indicated mean values

Figure 2 Skull proportions of wild and ancient domestic horses compared; for explanations see the Table 1.

Measurement |

Piatnitskoe-1 |

Dereivka |

Shatilov’s tarpan |

E. ferus uralensis |

E. przewalskii* |

Mandible length |

410 |

434 |

418 |

430.0-448.0 |

422.2 |

Length of lower cheek tooth row (P2-M3) |

171 |

176 |

177 |

180.5 |

|

Length of lower premolar series (P2-P4) |

82.3 |

88 |

|||

Length of lower molar series (M1-M3) |

80.7 |

78 |

|||

Length of diastema |

76.1 |

93 |

79.5 |

100.0; 102.0 |

83.6 |

Height of diastema in the middle |

42 |

||||

Mandible height below P2 |

59.5 |

53 |

46 |

59 |

55.2 |

Mandible height below M1 |

74.7 |

69 |

81 |

80.1 |

|

Mandible height below M3 |

107.8 |

95 |

110 |

109.2 |

Table 2 Mandibular measurements of ancient domestic and wild horses

The skull from Piatnotskoe-1 is characterized by relatively large cheek teeth (the length of upper tooth row attains 36.0% of the basal skull length). The relative size of teeth is close to that of Shatilov's tarpan (36.5%) and to the medium value of the horse from Botai (36.9%) and exceeds the tooth length ratio in the ancient domestic horses from Rurik Hillfort (34.2%) and Dereivka (34.0%).

Relatively short nasal bones represent one of the most remarkable morphological feature of the skull from Piatnitskoe-1. The relative length of nasal bones in the skull under study attains 39.7% of the basal cranial length. The relative length of nasals attains 51.1% in the "Shatilov's tarpan" and 53.6% in Equus przewalskii. It is not clear if the short nasal bones in the skull from Piatnitskoe-1 represents an individual variation, a characteristic of the Khazar horse breed, or a specific morphological character caused by domestication. The available data from literature give very little information of the relative length of nasal bones in and its variability in horses. It is important to mention that the domestic horse skull from Dereivka is also characterized by relatively short nasal bones (44.0%), which are just slightly longer than those in the stallion from Piatnitskoe-1. The dental morphology of the stallion from Piatnitskoe is typical for the species Equus ferus, while the relatively long protocone in upper cheek teeth clearly distinguishes the specimen under study from wild tarpan (Table 3 & Table 4). Actually, the skull from Piatnitskoe is characterized by the relatively longest protocone in P3-M2 among the specimens and samples involved in the comparison (Figure 3). However, the protocone of M3 is relatively shorter and this character approaches the stallion from Piatnitskoe to the subfossil tarpan Equus ferus ferus (Figure 3).

Measurement |

P2 |

P3 |

P4 |

M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

Length (sin) |

38.1 |

27.8 |

26.8 |

23.8 |

24.3 |

29.2 |

Breadth (sin) |

23.5 |

26.7 |

27.6 |

27.1 |

25.7 |

24.1 |

Protocone length (sin) |

9.7 |

13.6 |

14 |

13.3 |

14 |

14.1 |

Length (dx) |

38.6 |

28.6 |

27 |

23.3 |

24 |

30.2 |

Breadth (dx) |

23.4 |

26.8 |

26.8 |

26.8 |

25.4 |

23.9 |

Protocone length (dx) |

10 |

13.7 |

13.9 |

13.2 |

13.7 |

13.8 |

Table 3 Measurements of upper cheek teeth of the stallion mandible from Piatnitskoe-1

Figure 3 The relative length of protocone (Pr) with respect to the total crown length in upper molar series P3-M3: ancient domestic and wild horses compared.

Measurement |

P2 |

P3 |

P4 |

M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

Length |

33.4 |

26.5 |

14.6 |

25 |

24.5 |

32.1 |

Breadth |

17 |

18.8 |

18.8 |

18.5 |

17.7 |

16.4 |

Table 4 Measurements of lower cheek teeth of the stallion mandible from Piatnitskoe-1

Site |

L |

LDMdiaph |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdist |

Height at withers |

Piatnitskoe-1 |

216 |

30 |

46 |

45,9 |

136-128 |

|

Upper Saltov |

211 |

31,6 |

44 |

32,1 |

44,2 |

136-128 |

Upper Saltov |

225 |

32,3 |

53 |

48,7 |

144-136 |

|

Upper Saltov |

48,4 |

31,8 |

||||

Upper Saltov |

49,4 |

31,6 |

||||

Upper Saltov |

50,6 |

32,2 |

||||

Mohnach |

211 |

32,7 |

47,4 |

31,1 |

44,7 |

136-128 |

Table 5 Measurements of horse metacarpals from the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites

Site |

L |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdist |

DAPdist |

Height at withers |

Upper Saltov |

270 |

49,2 |

47,6 |

49 |

58 |

144-136 |

Upper Saltov |

262 |

50,4 |

48,5 |

48,5 |

36,4 |

144-136 |

Upper Saltov |

265 |

50,6 |

38,3 |

144-136 |

||

Upper Saltov |

250 |

45,9 |

39,6 |

46,8 |

36,7 |

136-128 |

Upper Saltov |

50,3 |

42,9 |

Table 6 Measurements of horse metatarsals from the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites

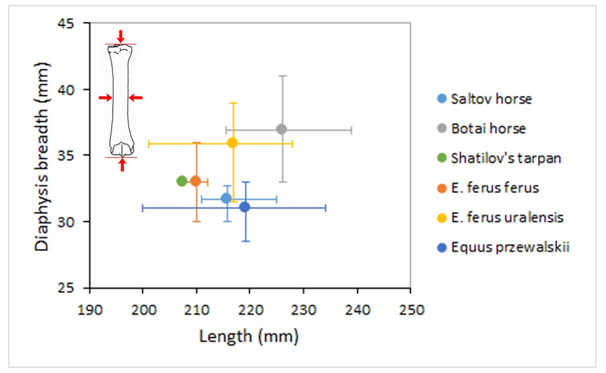

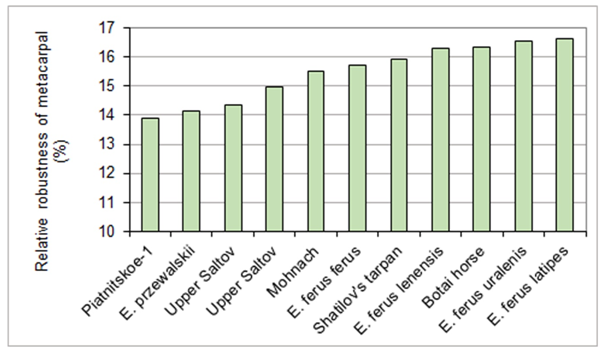

The estimated body mass of the stallion from Piatnitskoe-1 based on craniodental variables attains ca. 580 kg. The basal length of skull corresponds to 144-136 cm of the height at withers and belongs to the “medium height at withers” category according to the classification of Witt.18 Limb bones. Metapodials of the Saltov horses (Table 5 & Table 6) are comparatively gracile and approach in size and proportions modern E. przewalskii. Its metacarpals are much thinner than in the extinct horse E. ferus uralensis and thinner and smaller than metacarpals of the horse from Botai (Figure 4). It is necessary to indicate that metacarpals of Saltov and Botai horses are quite distinct and their measurements do not overlap. The complete metacarpal from Piatnitskoe-1 is characterized by the narrowest diaphysis among the compared horse samples (its diaphysis breadth/total length of metacarpal ratio amounts to 13.9%) and belongs to the so-called “thin legged horses” according to the definition given by Brauner.19 Another metacarpal from Upper Saltov with robustness index 14.4% also belongs to this category of horses. Two complete metacarpals from Upper Saltov and Mohnach with robustness indexes 15.0% and 15.5% respectively fall within Brauner’s “semi-thin legged” type of horses (Figure 5). Therefore, the Saltov horses are characterized by remarkably thin limbs similar to those of modern E. przewalskii and are distinguished from the robust horses from Botai and the extinct horses from Eurasia (E. ferus ferus, E. ferus uralensis, E. ferus lenensis, E. ferus latipes).

Figure 4 Metacarpal measurements of ancient domestic and wild horses. For series samples, medium values and absolute ranges are shown.

Figure 5 Metacarpal robustness (diaphysis breadth/total bone length) of ancient domestic, wild and Paleolithic horses.

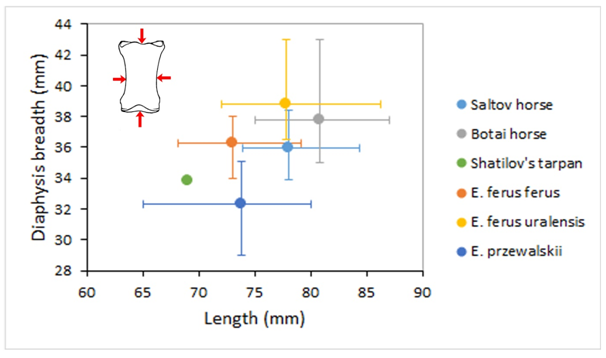

However, unlike E. przewalskii, the Saltov horse is characterized by larger and more robust first phalanxes (Table 7, Table 8 & Figure 6). Nonetheless, the first phalanxes of Saltov horses are still more gracile if compared to Botai horse and E. ferus uralensis, and elongated if compared to E. ferus ferus. The second anterior phalanxes show the similar differences in size and proportions among the compared samples, but the overlaps of variation ranges are broader (Table 9, Table 10 & Figure 7). The estimation of height at withers based on available complete metapodials gave the following results (Table 5 & Table 6): three metatarsals and one metacarpal from Upper Saltov correspond to the “medium height at withers” category, while one metatarsal and one metacarpal from Upper Saltov correspond to the Vitt's category “below medium height at withers” (136-128 cm). Two metacarpals (one from Piatnitskoe-1 and another from Mohnach) also correspond to this smaller class of horse height at withers. Evidence of hippophagy. The traces of butchering on horse bones and the age profile of horse individuals found in the Saltov archaeological sites are reported here as evidence of hippophagy practice. It is important to indicate that 12 of 43 individuals recorded in the archaeological sites under study are juvenile, while only three individuals (a male individual from Mohnach and two individuals from Piatnitskoe-1 that yielded half of the recorded horse individuals) are classified as senile (Figure 8). This demographic structure of horse remains is quite different from the early Iron Age Uch-Bash material, where senile individuals attained ca. 45% of the total individual number (18 individuals) and still different from the Iron Age Getic archaeozoological material from Moldova (Croitor, unpublished data) where juvenile individuals are quite rare (2 of 16 individuals).

Figure 6 Measurements of first anterior phalanxes of ancient domestic and wild horses. For series samples, medium values and absolute ranges are shown.

Figure 7 Measurements of second anterior phalanxes of ancient domestic and wild horses. For series samples, medium values and absolute ranges are shown.

Figure 8 Age structure of horses from Saltov-Mayaki sites compared to the age structure of horses from the early Iron Age site Uch-Bash (Crimea, Ukraine) (Croitor) and horses from Getic sites of Moldova (Croitor, unpublished data).

Site |

L |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdiaph |

DLMdist |

DAPdist |

Piatnitskoe-1 |

75.3 |

52 |

31.1 |

36 |

45.5 |

26.2 |

Piatnitskoe-1 |

83.5 |

54.5 |

32.3 |

37.5 |

46.6 |

26.6 |

Vodianoe |

79.5 |

57 |

38 |

38.1 |

47.7 |

24 |

Korobovy Hutora |

78.1 |

57.3 |

37.4 |

35.1 |

49.5 |

25.9 |

Korobovy Hutora |

74.3 |

56.5 |

38.2 |

35.3 |

42.7 |

23.5 |

Korobovy Hutora |

76.8 |

55.3 |

37.6 |

34.7 |

44.3 |

26.5 |

Roganina |

80.7 |

51.5 |

35.3 |

37.8 |

45.3 |

26.4 |

Upper Saltov |

81 |

58.8 |

31.7 |

36.8 |

45.7 |

26.1 |

Upper Saltov |

74.5 |

55.3 |

42 |

34 |

43.6 |

24.7 |

Upper Saltov |

76 |

55.2 |

37.9 |

37.4 |

46.6 |

27 |

Upper Saltov |

78.3 |

54.8 |

28.2 |

34.3 |

43.5 |

24.3 |

Faschevka |

80.2 |

53.8 |

33 |

36.7 |

48 |

29 |

Faschevka |

80.4 |

55.6 |

33.3 |

34.5 |

48 |

27 |

Faschevka |

84.4 |

59.7 |

34 |

38.5 |

47.7 |

27 |

Table 7 Measurements of anterior first phalanxes of horses from the Saltovo-Mayaki archaeological sites

Site |

L |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdiaph |

DLMdist |

DAPdist |

Korobovy Hutora |

73.6 |

55.8 |

37.2 |

35 |

44.2 |

23.6 |

Korobovy Hutora |

73.5 |

55 |

33.8 |

41.6 |

23.8 |

|

Korobovy Hutora |

71.5 |

52.3 |

38.8 |

33.5 |

42.3 |

25.2 |

Korobovy Hutora |

72.6 |

49.5 |

33.5 |

31.5 |

39.7 |

23.5 |

Korobovy Hutora |

74.2 |

48 |

34 |

32.9 |

41.4 |

22.7 |

Upper Saltov |

73.5 |

49.2 |

28.6 |

34.8 |

40.3 |

23.3 |

Upper Saltov |

71.3 |

53.5 |

38.4 |

35.3 |

41 |

24.7 |

Upper Saltov |

71 |

52.5 |

29 |

34 |

40.2 |

23.2 |

Upper Saltov |

72.6 |

49.8 |

27.5 |

31 |

40.1 |

22.9 |

Upper Saltov |

72.3 |

51.3 |

30.2 |

30 |

39.4 |

24 |

Faschevka |

76 |

60.6 |

32.5 |

37.3 |

46.6 |

27.1 |

Volchansk-2 |

75.3 |

55 |

29.6 |

33.3 |

40.4 |

24 |

Table 8 Measurements of posterior first phalanxes of horses from the Saltov archaeological sites

Site |

L |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdiaph |

DLMdist |

DAPdist |

Vodyanoe |

43.4 |

51.7 |

32.3 |

41.5 |

46.9 |

28.5 |

Korobovy Hutora |

40.2 |

51 |

44.3 |

46.5 |

24.5 |

|

Upper Saltov |

32.5 |

55.1 |

32.7 |

47.6 |

50.5 |

26.6 |

Upper Saltov |

35.5 |

49.8 |

29.2 |

43.5 |

48.7 |

26.1 |

Upper Saltov |

36.1 |

52.6 |

31.7 |

46 |

||

Mohnach |

40.1 |

50.3 |

32.1 |

41.4 |

45.4 |

28 |

Volchansk-2 |

42 |

58.9 |

37.5 |

47.4 |

52.4 |

32.6 |

Volchansk-2 |

37 |

53.3 |

31.4 |

44.7 |

51.3 |

25.5 |

Table 9 Measurements of anterior second phalanxes of horses from the Saltov archaeological sites

Site |

L |

DLMprox |

DAPprox |

DLMdiaph |

DLMdist |

DAPdist |

Korobovy Hutora |

37.2 |

50.7 |

32.7 |

41 |

46.2 |

25.8 |

Upper Saltov |

39.2 |

50.2 |

31 |

41.8 |

46.3 |

27 |

Upper Saltov |

35.5 |

47.1 |

30.2 |

37.8 |

43.6 |

26.4 |

Volchansk-2 |

38.3 |

53 |

34 |

45 |

49.2 |

26.9 |

Table 10 Measurements of posterior second phalanxes of horses from the Saltov archaeological sites

Cut marks on horse bones are recorded in two cases. This is a chopped os innominatum of a juvenile individual from Piatnitskoe-1 (ca. 3 years old individual characterized by the permanent I1 and deciduous I2). More frequent cut marks on horse bones (five cases, including cut marks on first phalanx, calcaneus, os innominatum, and femur) are discovered in the archaeozoological material from Upper Saltov. The support for the presumed hippophagy is also provided by the presence of pathological neoplasm on a mature horse humeral bone from Upper Saltov. Obviously, this animal was unsuitable for hard work and riding and could attain the adult age only if it was raised for the meat. Some of the horse remains are partially burned. This is the case of a young individual (M3 is in the initial stage of wear) from Mohnach. The skeletal remains are represented by a distal part of metapodium, anterior and posterior phalanxes and talus. All skeletal elements are charred. Another case of burn horse remains (5 isolated teeth and a fragment of long bone diaphysis) is recorded at Roganina site.

The horse remains from the studied Saltov archaeological sites belong to a rather small-medium size horse breed with gracile thin or semi-thin limbs (according to the classification of Brauner).19 The cranial length of the stallion from Piatnitskoe-1 and the length of metapodials mostly correspond to the medium height at the withers (134-136 cm), which is optimal for horseback riding. Fewer metapodials correspond to the height at the withers below the average, ca. 128-134 cm. The relatively thin metacarpals approach medieval Saltov horses to the most thin-limbed domestic and wild modern horse forms. The elongated thin phalanxes correspond to the gracile proportions of metacarpals of Saltov horses. The obtained data support the conclusions of Matolcsy5 on medium/small stature of Saltov horses based on material from Mayatskoe settlement. The medium/small thin-limbed morphological type of Saltov horse is rather uniform and there is no evidence on the presence of two or more different horse breeds. The reported earlier a rather large height at the withers of the stallion from Piatnitskoe-18 is based on a misuse of cranial measurements (condylobasal length instead of the basal length of skull).

The relatively large cheek teeth suggest a closer relationship of Saltov horses to the ancient horse breed from Botai (Kazakhstan). The exceptionally long protocone of upper cheek teeth in the stallion from Piatnitskoe-1 may be regarded as an evidence of insignificant hybridization with European wild tarpan. Therefore, one can assume that the Saltov horse breed is not local and apparently was brought to the Severski Donets basin from the east. Obviously, the medium-sized and thin-limbed Saltov horses represent an improved riding horse breed. Nonetheless, the recorded cut marks on horse bones and the exceptionally high number of juveniles (28% of the total number of recorded individuals) and very low number of seniles (7%) suggest the hippophagy practised by the Saltov culture bearers. The specific character of horse remains age composition from Saltov monuments becomes clear when compared with the age profile of horse remains from the Crimean Iron Age site (Uch-Bash) where senile individuals attain almost 45% of the total number of individuals, or if compared with Getic archaeozoological material from Moldova, where remains of juvenile individuals are rare (Figure 8). The partially burn horse skeletal remains found in Mohnach and Roganina suggest rather the horse implication in rites than hippophagy. The presence of horses in the arbitrary Saltov herd varies from 11.1% to 32.5% of the total number of domestic animals, marking a significant, but rather an unstable nomad cultural influence over the sedentary Saltov population.

The Early Medieval Saltov horses represent an improved riding breed with medium height at withers (134-136 cm), thin metapodials and elongated phalanxes. The relatively large teeth and long protocone in upper cheek teeth rather suggest the oriental provenance of this breed and the larger morphological distance from the coeval domestic horses from northwestern Russia and local wild tarpan E. ferus ferus. The relatively short nasal bone represent a specific morphological character of the single complete male skull available for study. The short nasal bones approach the Saltov stallion to the ancient domestic horse from Dereivka and distinguish it from "Shatilov's tarpan" and wild E. przewalskii. The significance of this character is not clear yet. The high proportion of juvenile individuals (28%) and few seniles (7%) in the archaeozoological material are interpreted here as an evidence of hippophagy. This conclusion is confirmed by the cut marks recorded on the horse skeletal remains. Few partially burn remains of horses may indicate the ritual importance of this animal.25−26

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.