Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

From a case study in a research project dedicated to the problems of Archeology of identity in an area of historic border with the city of Buenos Aires, current the San Vicente Partido, we explores the practices of donation and conservation of objects. It has been conducted the survey in the Sanvicentine Cultural Museum, located in the city of San Vicente, head of eponymous partido, of all those considered to be antiques, either by its historical or archaeological value, as well as others who are placed there as an ornaments. This survey was also complemented by documentation of diverse nature and carrying out an anthropological interview to one of the neighbors who, with a small group, takes care of the museum and its attendance sporadically. The information exposed allows us to understand some of the main characteristics of the aforementioned practices, not only in this type of museums, but also in the setting-up of private collections such as the one that gave rise to this particular museum. Finally, we discuss the implications that these objects had and still have in the construction of identities in this type of social contexts.

Keywords: museum, historical objects, archaeological objects, identities, san vicente, buenos aires, república argentina

After the process of creation of the national and provincial museums in Argentina in the middle of the s. XIX, Pupio1 analyzes how the appropriate context arose for the creation and expansion of municipal museums in the province of Buenos Aires during the first half of the s. XX. This author marks an important difference that will be applicable to the case under study and that is that unlike the first, ie the metropolitan museums, those located in small cities were practically always formed from particular collections or biographical, resembling the old cabinets of oddities.2 This is how they guarded, almost indistinctly, different types of historical objects, including also of archaeological origin, from the fine arts and even, from the natural sciences. Indeed, this type of museum and the Sanvincetino museum in particular, contain objects and also various types of documents3 among which stand out: photos, negatives, different types of documentary records (including old maps) and sometimes, also publications. In its great majority and as it happened with our case of study, the private collections of this have their origin in certain personages, generally transcendental within the history of the towns or cities of the province. This makes them not only the main donors but also the creators and directors of the institution, establishing, as a consequence, some of the strategies for the entry of new objects, heir selection and exhibition. As well as what happened at the national and provincial level, the institutions that were created at the municipal level, whether private or public, to protect, study and stage these collections, had as their primary objective to leave the private sphere, the house of family and be available for the communities of origin, in order to collaborate with the education of the public and then create an identity and a local culture.1 The emergence of these museum of San Vicente (Figure 1) presented here followed these general guidelines and, in addition, can be classified as a “single parent”.1,4 In effect, it was the product of the performance of Mr. Martins, who is constantly remembered by the community as its creator since, in addition, a space where objects are exhibited in his memory always stands out in a privileged place in the house-museum, that were his property coinciding with what happens with other museums of the same style.1,5 In this case it is about your desk and your valuables: your typewriter, your glasses, your watch, your mug, your knife, your mate, your camera, some of your papers, among the main ones. In the framework of the archaeological project that addresses the problem of identity processes in border areas and frames this work, the information gathered in the community and various means of dissemination generated by it coincide in defining the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum as a museum of manners rather than historical. This is due, essentially, to the characteristics of its origin, from a particular collection and, more especially, in accordance with its cultural-educational objectives focused on showing what it is to be Sanvicentino, as well as its subsequent growth, through of the collection of certain objects, aspects that we will develop later.

In order to know the process of origin, its objectives and the making of the museum, as well as the type of practices (conservation and donation) that are linked to the objects stored there and the identity implications that are derived from them, we were guided by the history of the development of museums at the national and local level and, also, by the theory of the Objects Cultural Biography.6 Although archeology already has a long history and its own methods to analyze the life history of objects through different approaches such as, for example, the sequence of events and decisions in the conformation of its operational chain, such as it has been demonstrated in numerous national and international works focused on the most technological aspects of objects; the method that implies the theory that objects can be addressed in his biography, almost in the same way as people, turns out to be more interesting for the objectives proposed here since it links historical, anthropological and archaeological information. This theory and method were postulated in 1986 by Kopytoff7 and was developed especially throughout the 1990s by several authors, among which we highlight Gosden and Marshall, especially in what has to do with objects’ agency and their performance.8

More recently and in spite of methodological difficulties for its application, it continues to be a valid method to reveal at least some of the relationships established between people and objects,9 as in the case presented here. In order to comply with our study objectives, a series of activities were carried out, among which are: the search for edited and unpublished information through different types of publications, including the dissemination ones, as well as informal interviews with different neighbors of San Vicente, the anthropological interview with one of the members that currently makes up the commission of friends of the museum and that is sporadically responsible for its opening to the public (key informant), the photographic survey of the exhibits, as well as the registration of their names, primary functions and ties established between them and their donors from the interview with our main informant. The main anthropological interview was of semi-structured type around seven axes that sought to know, through open questions, the conservation and donation practices that made the growth of this museum possible. In this sense, the questions were oriented to know and then evaluate, a series of issues related more closely to the implications linked to the processes of construction of the identity of San Vicente through the objects that are exposed there and, in some cases, from its biography itself:

For the photographic survey of the objects, the IFRAO scale was used as a metric and chromatic reference and in order to determine their names and functions, an anthropological interview conducted with a key informant was followed by a tour stopped next to the key informant in order to capture in our field notebook as much information as possible about each of the objects due to the absence of a seat book or any record in this regard.

Brief history of the origin and conformation of the sanvicentine cultural museum josé ignacio martins

According to the data collected on institutional and outreach web pages about San Vicente and its culture, as well as based on data provided by different local residents and by our key informant, we can say that the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum has its beginnings in 1987, when José Ignacio decides to create it from his particular collection of objects. For the support of the museum and as it is observed in the façade of the museum, from its creation and until the present time the museum is in charge of a commission of neighbors of which also originally he was a part.Martins was a personality of San Vicente. In fact, shortly after starting to reside in San Vicente, back in 1969, he began to stand out due to a series of actions that he led along with some followers or adherents of San Vicente. This is how, for example, in 1972 he created the Crusade Hernandiana Sanvicentina, which took horse from San Vicente to 10 gauchos in the area to the town of Pehuajó on the 100th anniversary of Martín Fierro. In addition to participating actively in politics and occupying various positions in the Department of San Vicente, Martins was the creator of the municipal shield (Figure 2) and the director of many of the cultural events of the place, as well as the monuments that stand out there: the chasqui, the guitar or those that remember General Viamonte and the painter Valls. It is interesting to note that although there is a history of San Vicente that traces its formal origins in the mid-s. XVII with the performance of prominent personages of that time,10 with these last monuments, a kind of recognition was materialized for those who are later considered as main protagonists of the place and part of the first settlers of the area.

The martins’ profile the collection and the museum

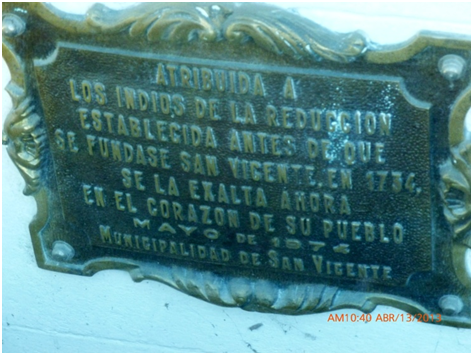

According to the collected data, although Martins had a classic collector profile, the place he occupied in the Sanvicentina society generated a prestige equivalent to that of a trained historian, archaeologist or museologist, allowing him not only to reconstruct part of the written history but also of the not yet written one. This can be exemplified by his attempt to build the history of a mission and a reduction based on the remains of a wooden cross with pedestal found in the area. Martins enthroned it in a central corner of the current city of San Vicente. This situation caused an official recognition of the fact that, in addition, it was materialized through reminder plaques (Figure 3) (Figure 4). It is interesting to note that even though the effective presence in San Vicente of this mission or reduction has not been documented historical nor archaeologically10,11 this monument constitutes an important milestone in the history of the town, to the point that it operates almost in the manner of a founding myth.

Figure 3Cross of Reduction restored and enclosed within a glazed construction in one of the corners of the central square of San Vicente city.

Figure 4Reminder plate with which the recognition of the attribution of the cross to the mission of the Indians of the reduction that, according to Martins, would have existed in San Vicente before its foundation.

From the profile carried out by Martins it was not difficult then to impose his own collection of objects as the inaugural of the projected museum but, in addition, to impose certain criteria that, although not written, can be read in the narrative that is observed in the collection exhibited in the different rooms. This narrative imposes the discourse of a colonial origin of the town of San Vicente, over the overlapping presence of native Indians in the area. To do so, a series of objects is shown, supposedly commonly used in the daily life of these ancient settlers, who only highlight certain socio-economic sectors. In effect, these objects speak to us, mainly, of the well-to-do classes of San Vicente and of the figure of the gaucho or country man. In this sense, although the collection was and remains receptive to the donation of ancient objects, which in some cases they recognize as historical and in others as archaeological, preserved by the different families of the city and the partido. As a consequence of the processes that we have been able to differentiate and that distinguish between a differential family preservation and a selective donation, the museum's collection is composed of a number of objects that, although very heterogeneous, do not represent the entire history of this border area. In addition, different causes that we have not investigated in depth made that, despite the different regulations that were happening in the last half of s. XX to formalize the situation of private collections and local museums, centralize their administration and control the cultural policy of the province of Buenos Aires,1 as well as the various attempts made by the creator of the museum and the neigbours to obtain a greater recognition by different governmental bodies, the museum remains still outside the orbit of Culture and /or Education of the Partido de San Vicente.

In these senses, in this museum are not the main technical aspects that are part of the common guidelines in museums in the province. Regarding this and in relation to the implications of family conservation practices and selective donation, our informant assured that the absence of registers would be largely due to the fact that a large part of the data referring to the objects were stored in the memory of the friends of the museum, what was shown to us when we were traveling together, object by object and he contributed data related to the use, donor family and a brief history of how that object had arrived there. In this way, our key informant was putting the object itself as analog or image of human memory and, in this sense, as a solid marker of that memory supposedly shared by all the members of the local community. These data could be easily recognized by any Sanvicentino, marking the difference with the others, which included me. Regarding the current state and situation of the museum, especially in regard to its lack of insertion in any of the spaces of the government orbit, as well as the lack of funding sources for its maintenance, it continues to be sustained by the goodwill of the friends of the museum, without a fixed day and schedule for the attention to the public, even when within their goals is the possibility of organizing visits, such as those that occasionally take place for schoolchildren in the locality or as gatherings , which some years ago organized more frequently for the meeting of the neighbors, the people of San Vicente.

Towards a cultural biography of museum objects that contributed to the conformation of current sanvicentine identity

Analyzing objects only from the formal, stylistic and functional point of view implies a traditional typological theoretical framework that ignores their relationship with the subjects who thought, produced and/or used and reused them in different contexts or instances. In this investigation and considering the construction of identities in border areas, the analysis of the conserved objects is framed in a study that pretends enter part of the life history of those objects,12 which some authors reformulated from a more anthropological point of view, using another language, scale and objectives, calling it cultural biography of objects.6 In effect, from this last analytical option the researcher aims to examine objects or artifacts in particular or of certain chronological and/or geographical sets in their relationship with people and vice versa.9

The difference between one and another approach to the analysis of objects (the traditional one and that of the biography of the objects) becomes evident when we observe that even when it comes to objects that remain decontextualized and static in a showcase, on a table or a shelf of the museum, many of them retain connections with the people who produced them, but also with those who used them and/or even donated them. They even continue to acquire meanings over time in their connection with new people. For example, a plate of earthenware is important according to its place of origin and date of production, but it is also according to the person who used it and/or donated it to the museum. Thus and as archaeologically demonstrated in the city of Buenos Aires, a pottery of European origin may not have been the most expensive in its place of origin but, in the migratory context, increased its value to be in the hands of a few, with certain surnames, elites and/or under certain circumstances or uses.13

This approach, together with the analysis perspective of Connerton14,15 about being able to determine what societies remember or silence, is then useful to analyze this case since, in general terms and according to the different contexts, it is applied universally.6 Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize here that the context and its in-depth knowledge is really decisive in order to understand the agency of objects. We consider in short that this analytical perspective can be applied to museum objects since the objects that extend their agency or rationale over time, through different systems of understanding, act as a kind of reincarnation or biographical entanglement.9 Consequently, it can be said that there are certain objects that are displayed in museums of this type that function as solid memory markers, even with material modifications through. Thus, after the typological functional characterization of the objects, in this particular work we concentrate on the identification and preliminary explanation of family conservation practices and selective donation that led to these objects being part of this museum. In this sense we stop at the analysis of the type of relationships that these objects entered into with people, in this case with those that conserved them and then donated them and vice versa. To do this, we presents two types of objects that, formally and from a traditional typological and descriptive analysis, could be defined as first necessity or commodity artifacts, earthenware dishes and a pava. However, either by its context of use, its style, distribution circuit and particular relationship with certain characters of San Vicente's history, they have an added value that resembles what in terms of the cultural biography of the objects is considered a gift6 a precious commodity. Under the analytical perspective of the cultural biography of the objects, both can keep a value conferred by the relationships that certain people entered into with them, they can even continue to accumulate value, even when those people are no longer there.In fact, it is not common dishes and a pava, they are the dishes of the Luzzy Murray family and Mr. Martins' pava. These are common objects in the daily life of their users but the value they have today when being exposed in the museum is a consequence of the life history that can be counted from them and that is linked to their materiality, with their use in contexts individuals and with the role of their respective owners, who kept and donated them (differential family preservation and selective donation) to the museum.

The dishes of the luzzy murray family

The case of earthenware dishes featured in the homes of rich families, as a sign and symbol of their wealthiness, is often repeated throughout the history of the West, especially from the conformation of what Romero16 called the mentality bourgeois that began to characterize timidly towards the s. XI to some sectors of the incipient European cities, for that reason it was also called urban mentality. The same continued to grow over the centuries to reach America and well into the s. XIX, when it begins to dispute the place with the cultured bourgeoisies, the progressive elites. According to Romero, this mentality reinforces its more traditional aspects and its old beliefs precisely in the s. XIX and a good example of this is Romanticism, a cultural phenomenon that confronts the bourgeoisie with the consequences of the Industrial Revolution first and the emergence of the industrial proletariat later. In this sense, we can say that the societies of that time transform their structure according to two possible models:

Although this proposal is basically applicable directly to the old continent, the waves of immigration from Europe that populated these first border areas, such as the city of Buenos Aires, makes it possible to establish a certain parallelism or inheritance of mentalities/ideologies that, without a doubt, anchored in certain ways to occupy the new spaces and build a life through certain materialities, objects that allowed to look like, as politically it happened in the time of Rosas with the punzó badge. The changes that occur in the middle of s. XIX and that turn out to be transcendental, especially in this mentality, is what could explain a part of the Sanvicentina society of that time, time in which the Department is conformed and the transfer of the old town takes place to its current location. This society of the mid-s. XIX Sanvicentina is the one that is most appreciated in the narrative of this museum. Maybe as a way to cling to that mentality that was associated and continues to do so in the discourse of some Sanvicentinos, with the most traditional values of society, those that also refer to the first settlers who came from Europe to the area at the beginning from the s. XVII. Returning to the case we took, for example, the donation of the Luzzy Murray family consists of a series of 7 plates arranged on a shelf specially designed to show them. Although they offer a variety of styles it could be said that, in general terms, they refer to the end of s. XIX and early-middle of s. XX. Even though some plates of European origin are included in the repertoire, such as mark Alfred Meakin (England); there are also national industry, such as the mark Festival (Figure 5(A)) (Figure 5(B).

Although we cannot go into the biography of each of the dishes in particular we can say that, in general and according to the survey made, these dishes were conserved due to their materiality, provenance value or connection with certain family members (differential family conservation). Also, their selective donation is because they constitute a sample of the belongings of Mrs. Luzzi Murray, recognized by San Vicente as someone important and local. From this point of view the cultural biography of these dishes rather than reinforcing the memory of their function or use in themselves, reinforces the memory of surnames, of a family that occupied a certain place in society. This is confirmed when our key informant tells us that this biography is used as a teaching resource to show part of the identity of the San Vicente society in the occasional visits of San Vicente schoolchildren and tourists.

The pava of Mr. Martins

The pava of Mr. Martins, used by the gauchos on their way to Pehuajó in commemoration of the centenary of the publication of Martin Fierro book, is clear typology of mid-s. XX. As an object of common or daily use, commodity, it has no greater significance than the one given by the habit of drinking mate served with it. Hence, it is a clear example by which some Sanvicentinos currently identify this museum with a museum of customs. Nevertheless and as previously anticipated, it is the participation of this game that made this object particularly valuable. Hence, it is an important object in the collection and occupies a prominent place in it. In a similar way to the previously mentioned case of earthenware dishes and from the point of view of cultural biography, this more than reinforces the memory of its function or use in itself. The pava of Mr. Martins reinforces the memory of the founder of the museum as well as its agency in a historical event. This is another of the important cases in which the object is used as a didactic resource to show Sanvicentina identity. Implications of the conservation and donation practices of the objects that make up the exposed collection of the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum If we start from the assumption that both the objects that are and those that we know that were part of the material culture of the place but have not been preserved or donated, talk about the mechanisms, generally symbolic, through which the "Systems of belonging and differentiation" that, according to Crespo and Tozzini show or "silence" the history of the place conforming "a privileged observatory to apprehend the relations of power in play in the zone”;17 in this case, we can deduce some of the implications of the practices that were put into play to show who can be considered as local natives and, more specifically, from San Vicente.

In this sense, despite not having a great current recognition from the political-institutional point of view, the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum is a product of the processes of belonging and differentiation that begin very early in the area and continue to take hold throughout the year, throughout the twentieth century, even to the present. In effect, the differentiation between Sanvicentino and non-Sanvicentino, which can be seen in local early documentation, is still possible to be observed both in the narrative of the museum and in the dialogue with those who are currently considered neighbors of San Vicente. It is noteworthy that this differentiation is the product of the construction of the identity of San Vincente for ascription and not only by birth in the place and demands to be recognized by the community, self-nomination is not enough. From this position and if we consider the "heritage" of the museum as a social construction composed of all those objects that have been selected by a certain group of people for its symbolic value in its different aspects: social, economic and/or political,17 we can deduce that this heritage not only represents the group or those they want to represent, but also excludes any object that represents another group (s) with whom they do not identify themselves. In this sense, it is not by chance that the objects shown do not identify the original inhabitants, the Indians, of the area.

Indeed, although the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum seems to show a unity between the past and the present, it uses clear resources according to a narrative or expository historical narrative that privileges certain groups over others. Thus, while it shows in the last shelf of a glass cabinet only a dozen objects that speak of a pre-Hispanic past common with the macro region, it exposes in several spaces and in abundance and detail those objects that were part of the daily life of the settlers of the old town and current city of San Vicente. They are the objects that belonged to people coming from Europe who also formed the elite of the place. But it is also about those objects that represent the typical Sanvicentino that legitimizes the sectors of power and/or more socially recognized. Despite this general assessment, there is no single theory or explanation to understand how each object is related to the relationships previously established with it.6 In the region bordering the city of Buenos Aires, as well as in it, the welfare, prestige and/or power of a person or social class manifested itself through a series of objects, not only of different materiality but also of different typology. According to the analyzed examples, they are not only valuable for their materiality, productive process, technology or provenance, but also for their meanings accumulated over time. In particular and in addition, it could be said that the objects exhibited in the Sanvicentino Cultural Museum describe the prominent people in the Sanvicentine society.

In this way, although almost silently, this museum still operates actively on the inhabitants of San Vicente through guided visits to schoolchildren or through meetings in the format "tertulias" (conversations). These two formats describes their histories, also reinforces a social order that identifies the majority of those who currently recognize themselves as Sanvicentinos. In this sense, the objects that narrate the history of San Vicente are generically identified as historical and it is not easily discriminated when, or from what moment, they can identify archaeological objects, except for the few pieces that are linked to the Indians. If we consider that historically San Vicente Department was part of what was known as the "Buenos Aires campaign", border area to the early city of Buenos Aires and was originally conceived as a "desert" space of "population" but stalked by the an Indian who roamed, it is not surprising that the aforementioned museum, like the local histories, has focused on the colonial origin of this space, silencing the past of the original communities.

In this sense, it is interesting to note that within the narrative of the museum there is space not only for some objects of Indians but also for the pedestal of a wooden cross that, according to Martins, was the product of the 17th century mission around to the San Vicente lagoon. Until now, the missionary origin of their ancestors is more a myth than a history, since this mission was archaeologically sought without success through the only work antecedent to ours.11 Academically speaking, the mission alluded to in this mythical history could be the one that is currently referenced in a space located further south of the old town of San Vicente and close to the possible location of Fort El Zanjón, from the s. XVIII.19 What is interesting here of this story is, in any case, to understand the role of Martins as historian and archaeologist, when achieving the official recognition of the time of said history, entering the cross of the reduction in one of the corners of the central square of the city of San Vicente. It is worth mentioning, however, that currently many people, including our key informant and culture authorities, recognize that this cross could be the product of the missions carried out later, during the 19th century, for the pacification of the area.

In short, the narrative of the exhibition can be read through the exhibits according to a scale of importance that indicates that there were native communities, Indians, but the settlement was the product of the immigrants, preferably Europeans, who at the beginning of s. XVIII were established following the founding construction of the chapel of Vicente Pessoa in the historic town of San Vicente. These characteristics do nothing more than bare the conflictive processes generated by the heritage, generally opposing, as in many other cases,19 the original communities or part of them with the state organisms.17,20 The practices of family conservation and selective donation of certain and preferential types of objects reproduce the power relations that were characteristic in this peripheral border area of the city of Buenos Aires. In effect, or in other words, on this frontier as well as in the city itself, the population was whitewashed using, in addition to the written history, the story told through the objects preserved by the families of neighbors and donated selectively.

In addition, we observe that it is still necessary to decipher what are the characteristics that make that some objects of the official history can be considered historical or archaeological. In fact, our key informant was surprised when we asked him about it at the end of the interview because from this point of view the objects exposed are only historic or ornaments, according to the function that they fulfill in the exhibition. Returning to the examples mentioned in relation to the private collection of Mr. Martins, as well as those donated by the Luzzy Murray family, the objects acquire significance and agency in the construction of the Sanvicentine identity, thanks to the value acquired by their links with their bearers or users, rather than because of its origin and technology. Something similar to what happens with the transcendent characters of San Vicente's history, who stand out and are recognized as Sanvicentinos for their performance but also for their belongings. In this sense, we consider that starting from a material and documentary analysis that goes from the s. XX backwards will allow us to better understand the subtle differences in the agencies of people and objects that await us in the archaeological sequence of this settlement. Especially because, as Gosden points out, "Periods of change are important in bringing out the relationships between people and their object worlds, looking at that strands of continuities in the requirements objects of people, as well as the changes".21

To Lic. Mariela A. Petuaud, archaeologist Sanvicentina, with whom I was able to get into this case of study and we relieved this museum. To the Secretary of Culture, Mr. Javier Carbone, who facilitated at all times the beginning and continuity of this study project in the San Vicente Partido. And Mr. Osvaldo Lara, neighbor and friend of the museum, who opened us with great enthusiasm the doors of it.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.