Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 3

Doctor, Institute of Art History, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Correspondence: Rózsa Juhos, Doctor, Institute of Art History, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary, Tel +3670 2939 874

Received: February 07, 2018 | Published: May 10, 2018

Citation: Juhos R. The sepulchre of Christ in arts and liturgy of the late middle ages. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2018;3(3):263-271. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2018.03.00103

The purpose of this paper is to explain the special use of medieval Holy Sepulchres within the Good Friday and Easter rituals with the aid of liturgical sources and formal examination. As a result, it can be highlighted the features of Holy Sepulchre, which make it different from other liturgical furnishings of the churches. Both the design and the function have a mimetic character different from the liturgical-commemorative sign-usage of the Holy Mass.

Keywords: medieval art, function, liturgy, devotion, tomb of christ

Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem identified as the tomb of Christ was in the focus of medieval religion. Its structure inspired a huge number of cemetery chapels, baptisteries and other central buildings all over Europe.1 From the very beginning Holy Sepulchre imitations were founded by pilgrims in commemoration of their pilgrimages to the Holy Land. The recent paper focuses on the Holy Sepulchre representations set up in the interior of church buildings which had a role in the liturgical re-enactment of the death and resurrection of Christ. Starting from the formal point of view, the surviving objects allow us to elaborate a typology and make a chronological order to see the course of development.1From the 11th century onwards Holy Sepulchre representations began to be elaborated in the interior of the church buildings (Figure 1) From around the end of the 13th century Holy Sepulchre copies became a symbolic representation in the form of a Gothic memorial sculpture.2 In the course of the 14th century a canopied monument with a giant figure of Christ lying in the tomb came into being (Figure 2). The types of wooden sarcophagus and wooden chest were also used in parallel with the stone monuments (Figure 3) (Figure 4). Around 1500 the free-standing shrine developed, which can be characterized by a very ornate canopy above a sarcophagus (Figure 5) (Figure 6).

Figure 3 Holy Sepulchre, Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe (Upper-Rhine, middle of the 14th century).

Figure 6 Holy Sepulchre from the Benedictine Abbey of Garamszentbenedek/Hronský Beňadik (SK), Christian Museum, Esztergom (c. 1480/90).

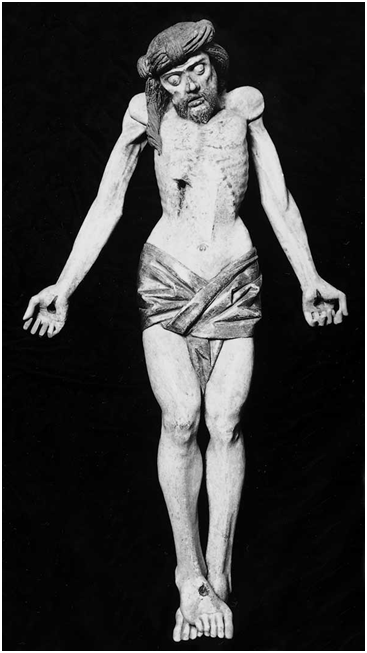

Another method of examination of Holy Sepulchre representations is the functional aspect which cannot be independent of the formal point of view. A distinction can be made according to the object of the entombment. Especially the permanent structures, which include the life-sized figure of the dead Christ built-in, have a small receptacle for the consecrated host to be placed inside (Figure 7).2 Further there are Holy Sepulchre structures which were used for the deposition of a wooden sculpture of the dead Christ. A special type of the entombment-figure is the crucifix with movable arms intended to be detached from the cross before the burial, in this way a whole entombment scene could be enacted (Figure 8).3 According to the object of the deposition the name of the symbolic entombment can be Depositio crucis or Depositio hostiae. On Easter morning the same objects were removed from the sepulchre, the corresponding ritual is named elevatio crucis or elevatio hostiae. There is a combination type as well, during which both object were buried.

Figure 8 Crucifixion with mowable arms from the Benedictine Abbey of Garamszentbenedek / Hronský Beňadik (SK) (c. 1480/90).

From a functional point of view we can distinguish between permanent structures made of stone and temporary wooden Holy Sepulchres. The permanent monuments situated in the nave of churches could have a role after the Easter season, but they could be seen throughout the year outside the official liturgy as a devotional image as well. The movable ones were easy to carry and they are assumed to have been removed from the church after usage during the feast of the Holy Week.

The function of Easter sepulchres can be examined starting from the structure itself and/or with the aid of contemporary liturgical sources. Since it is almost impossible to find liturgical sources which can be assigned to a given church at a specific period with complete certainty, the Easter Sepulchres frequently remain the primary source to explore the original use. No attempt has been made to gather written sources of official ceremonies in the related area and examine how a given Holy Sepulchre could be adapted to the local liturgical practice.4 There would be a little chance to accomplish such an undertaking because of the sporadic and accidental survival of both liturgical sources and Holy Sepulchres. The research into functions during the liturgical observances with the aid of liturgical texts can lead us to general statements, which cannot be used directly for the examination of every single Easter sepulchre. Neil C. Brooks searched into the design and nature of Holy Sepulchre constructions from the rubrics of available liturgical manuscript and obtained types of Holy Sepulchres, which are hard to compare with the surviving examples.3 Nevertheless the purpose of this paper is to see how liturgical texts can support the endeavour to explain a special detail of some Easter Sepulchres. The element under recent discussion is the receptacle and the place of the consecrated host.

1To a typology of Holy Sepulchres see: Schwarzweber A. Das heilige Grab in der deutschen Bildnerei des Mittelalters. Albert, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1940. p. 10−60. Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini through the Ages. Its Form and Function. Virginia: Peeters, Leuven-Paris-Sterling, 2000. p. 45−108.

2Becksmann R, Echtenacher G. Der Freiburger Münster. Regensburg: Schnell & Schneider; 2011. 219 p.

3Taubert G, Taubert J. Mittelalterliche Kruzifixe mit schwenkbaren Armen. Ein Beitrag zur Verwendung von Bildwerken in der Liturgie. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Vereins für Kunstwissenschaf. 1969;23:79−121. Takács I. Garamszentbenedek temploma és liturgikus felszerelése. In: Paradisum Plantavit, editor. Bencés monostorok a középkori Magyarországon. Exhib. Kat. ed. Takács I. Pannonhalma: Pannonhalmi Bencés Főapátság, 2001. 182 p. Figure 52.

4Kolumban Gschwend gathered the historical evidences of medieval Good Friday ritual in the area of diocese Brixen, but he could not present any art object. Gschwend K. Die depositio und elevatio crucis im Raum der alten Diözese Brixen. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Grablegung am Karfreitag und der Auferstehungsfeier am Ostermorgen. Sarnen: Louis Ehrli & Cie; 1965.

Some of the Easter sepulchres with a separate place for the sacrament can be regarded, in some respect, as a temporary sacrament house as well. A very popular method of discussion focuses on the functional and semantic resemblance between Holy Sepulchre and sacrament house. For example, Annemarie Schwarzweber conveyed the suggestion that some of the 14th-century sacrament houses, like the one in the church of St Sebaldus in Nuremberg and one in the St. Jakob von Rothenburg ob der Tauber (Figure 9) (Figure 10), which have an entombment depiction underneath the sacrament niche could also be used for the deposition of the Eucharist on Good Friday.5 According to her interpretation these tabernacles must have had a double function, namely they could reserve the consecrated host after every mass and they could be also used on Good Friday as a symbolic burial place of Christ.

Justin EA Kroesen4 also laid the emphasis on the similarities between Holy Sepulchre constructions and sacrament houses on the basis of their functional and formal relationship.4 The receptacle for preservation of the consecrated host was often interpreted as the tomb of Christ in the Gallican rites.6 From the 6th century Expositio Brevis antiquae liturgiae gallicanae makes the formal and semantic relation clear: “Corpus vero Domini ideo defertur in turribus, quia monumentum Domini in similitudinem turris fuit scissum in petra et intus lectum, ubi pausavit corpus dominicum, unde surrexit Rex gloriae in triumphum”7 The receptacle of the consecrated host as well as the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem are described as “tower”, which allows us to associate a tower shaped sacrament house placed on an altar, such as the one from Sénanque (Figure 11). The form of the Holy Sepulchre chapel in the cathedral of Konstanz (Figure 1) could be derived from this type of sacrament-shrine in a form of a central-plan edifice.8

Easter Sepulchres in English cathedrals have their place in the north wall of the chancels,5 the same location as the tabernacles have in most of the churches, which can be considered as proof of functional and semantic connection between the two liturgical objects.9 Both elements seem to be combined in some examples in south-west Germany. The St Gallus church in Ötlingen has a sarcophagus enclosed in the north wall of the chancel, the front of which is decorated with reliefs of the sleeping soldiers (Figure 12).10 Above the sarcophagus there is a 1.3 metres wide recess presumably for the sculpture of the dead Christ or a small crucifix. On the top, under the keel arch a tabernacle takes place. Almost the same arrangement and the same location can be seen in Schönau im Wiesenthal and in the evangelic church of Mappach, but they must have been unusual and they can be localized to a small area.11 This interpretation of Easter sepulchres which underlines the functional, formal and semantic connection with the tabernacle leads us to an overlap of two liturgical functions. Moreover we can find semantic relations between altar and Holy Sepulchre as well. Amalarius von Metz in his Liber officialis interpreted the altar as sepulchrum Christi: “Per particulam oblatae inmissae in calicem ostenditur Christi corpus quod iam resurrexit a mortuis; per comestam a secerdote vel a populo ambulans adhuc super terram; per relictam in altari iacens in sepulcris”.12 According to that the presentation of the consecrated host in a chalice has a meaning of Christ’s resurrection. On the base of semantic connotations it is easy to be led to the conclusion that every object used in the liturgy as a place for the sacrament could serve as a symbolic grave of Christ on Good-Friday as well. The question ought to be examined with the aid of liturgical sources of the feast ceremonies in order to see whether the practice could support the semantic connotations.

The altar as a place of the sepulchrum for the depositio ceremony proves to be right. The Prüfening manuscript from 1489 contains the following rubrics on the Easter ceremonies: “de corpore dominico in sarcophago in altari Sancte Crucis loco dominici sepulchri preparato recondendo” and “et fit stacio ante altare Sancte Crucis quod antea a custode loco Domenici Sepulchri lintheo magno specialiter ad hoc apto velatum existit.”13 The altar of the Holy Cross was the place of the sarcophagus used for the depositio. But the special use of tabernacles during the triduum sacrum cannot be proved with the aid of liturgical sources. If the sacrament was carried back to the sacristy or tabernacle after the Good Friday mass, we cannot speak about depositio hostie. In church St. Emmeran of Regensburg there was the liturgical observance that the sacrament was carried back to the sacrarium right after the depositio: ’Interim dominus abbas et sacerdotes locaverunt crucem et corpus domini super sepulchrum et ipsum operientes lintheo incensant et cantant responsorium. Tunc dominus abbas clam sub casulam accipit corpus domini precedentibus cum cereis portant ipsum in sacrarium more solito reservandum.’14 The consecrated host did not remain on the sepulchrum and only the cross was raised and taken back to ‘lokum suum’ in the course of the elevatio. The host and the crucifix were stored separately and the rites of the triduum sacrum were designated as depositio crucis and elevatio crucis. Despite the ritual taking place on the day of Christ’s death and entombment, carrying the consecrated host to its preserving place does not receive the name of sepulchrum and does not get the meaning of burial.

Taking examples of deposito crucis et hostiae, that is burial of the cross and the host together, we find that there must have been a place from which the sacrament was carried out for the Good-Friday mass. This part of the host came from Maundy Thursday because no host was consecrated on Good Friday. A proper reservation of the sacrament after the Maundy Thursday mass needed a place, the reposoir, which was never designated as “sepulchre” in any cases when a Holy Sepulchre was set up for the Good Friday rite.15 From the late 16th century onward the reservation of the Eucharist became an elaborate, processional form and the place of Repose received the significance of the sepulchre. There is no evidence, however, for the place of Repose to have the particular symbolic significance of the sepulchrum in the Middle-Ages and it seems not to have had a placement different from the regular housing of the sacrament. When the sacrament was buried symbolically into the sepulchre there must have been a safety place as well which the Eucharist was carried back to. This place could be a sacristy or a lockable tabernacle. The 15th-century ordinarium originated from Blaubeuren points out the difference between the two places: ’Et nota diligenter, quod corpus christi non est dimittendus per illud triduum in loco sepulture, nisi repositum sit sub firma custodia: et testibus seu custodibus circa illud psallentibus adhibitis: Alias vero, ubi huius modi custodia ac psallencium vigilia non fuerit adhibita. Sacerdos finitis vesperis corpus dominicum in suum solitum reportet reservatorium, ubi bene clausum conservetur.’16 The “reservatorium” is the proper liturgical object that preserved the Eucharist, whereas the sepulchrum could not house the sacrament without its strict guarding. The sepulchrum appears not to have been identical with the regular place of the consecrated host.

Seeing that there must have been a place which preserved the Eucharist after the Maundy-Thursday mass for Good Friday and another place on Easter day which the sacrament was carried back to, both locations of the sacrament seem to have been altered from the place of sepulchrum. The tabernacle could serve as the place of Repose of sacrament on Maundy Thursday and could be a “reservatorium” for the elevated host. The tabernacle could serve both purposes in the same liturgical observance. But it is hardly to be expected that the tabernacle worked as sepulchrum during the triduum sacrum in that cases when the elevated sacrament was ordered to be carried back to the “reservatorium”, which would have been most likely the tabernacle again. The sacrament house appears to be more suited for the rites before and after the entombment ritual. We cannot exclude the possibility that a sacrament house was used for the deposition of the sacrament in churches, in which there were no stone or wooden representations of the Holy Sepulchre. However, most of the liturgical sources report about temporary structures set up on an altar covered or surrounded with a cloth as we can see in the 10th-century Regularis Concordia: “Sit autem in una parte altaris qua vacuum fuerit quaedam assimilatio sepulchri velamenque quoddam in gyro tensum quod dum sancta crux adorata fuerit deponatur hoc ordine.” A shrine placed on a bench or stool worked as a sepulchrum at St. Gall: “portat sanctuarium in medio chori ponens super scampnum velato panno.”17

For lack of a permanent or movable Holy Sepulchre intended for the depositio rite, the St. Sebaldus sacrament house had not the function of a sepulchre for sure. A temporary structure was used instead: a silver coffin (Sarg) on an altar-table represented the burial place of Christ.18 The location of the temporary sepulchre, as Gerhard Weilandt suggested, was in the south part of the chancel near the Lady-altar.19 The object of deposition was only the consecrated host. Neither the lack of a Holy Sepulchre construction nor the practice of depostitio hostiae led to the use of tabernacle as sepulchrum despite its depiction of entombment, as it happened in the case of Nuremberg and Bamberg. An entombment scene on the sacrament house cannot be attested its special function in the Good Friday ritual, only the semantic connotations between the two liturgical objects is indicated. The South-German combination of sacrament house and sepulchrum-recess situated in the north wall of the chancel signifies the close inherence of both parts of the construction. The framework arranges the two elements into a coherent composition in St. Gallus church of Ötlingen. Since there is no single sacrament house in the church besides the combination type, it is likely to have been used after every mass for preserving the consecrated host. But the separate place underneath the tabernacle can imply that the tabernacle was not enough and not sufficient for the Good Friday and Easter liturgy.

5Schwarzweber A. Das heilige Grab. 1940. p. 45.

6Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini. 2000. 71. p., Kroesen JEA. Heiliges Grab. 2000. 291 p.

7Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini. 2000. 71 p.

8Lexikon der Christlichen Ikonographie. Hrsg von Engelbert Kirschbaum Bd. II. (Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, 1970) 183−185.; Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini. 2000. 72 p.; Viollet-le-Duc E. Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l’Epoque Carloringienne à la Renaissance, Gründ et Maguet, Paris I. 247 p.

9Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini. 2000. 69 p.

10Kroesen JEA. Heiliges Grab. 2000. 292 p.

11Ibid.

12Kroesen JEA. The Sepulchrum Domini. 2000. 71 p.

13München Staatsbibliothek. ms. clm 23018. 66b. In: Lipphardt W. Lateinische Osterfeiern und Osterspiele Vol 2. NewYork: Walter de Gruyter, Berlin; 1976. 311 p.; Taubert G, Taubert J. Mittelalterliche Kruzifixe. 1969. 92 p.

14Ordinarium, Regensburg, St. Emmeran. München, Staatsbibl. ms. clm. 14073. 15. sz. 40a-40b. In: Lipphardt W. Lateinische Osterfeiern. 1976. 325 p.

15Brooks NC. The Sepulchre of Christ. 1921. 50 p.

16Ordinarium 15th century, Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek Hb I. 77. 18a, In: Lipphardt W. Lateinische Osterfeiern, 1976;2:201.

17Brooks NC. The Sepulchre of Christ. 1921. 62 p.

18Item ein silberein sarch, den man nuczt am karfreitag zu dem grab, wigt 21 mark 12 lot” „ein altarstein darunter” In: Weilandt G. Die Sebalduskirche in Nürnberg. Bild und Gesellschaft im Zeitalter der Gotik und Renaissance. Petersburg: Michael Imholf Verlag; 2007. 167 p.

19Ibid.

Comparing structures of Holy Sepulchres used for the depositio hostiae and that of the tabernacles with depiction of entombment, we can perceive differences in their composition and iconographical program. The sacrament house in the east choir at St. Sebaldus in Nuremberg has a large host-shrine in the middle surrounded by a complex architectural framework (Figure 9) The figural decoration follow a strict hierarchy, on the top of which the sacrament-shrine occupies and they were arranged in the form of a cross.20 Three scenes were carved vertically in the main axis of the host shrine: an entombment scene below, a Gnadenstuhl between the Virgin and John the Evangelist above the shrine and a Last Judgment on the top. The horizontal part of the cross includes a Man of Sorrows figure on the right and presumably the figure of Mater Dolorosa stood in the empty niche on the other side. Flanking the main axes a series of single figures are between the buttresses including angels with arma Christi, the patron saints Peter and Sebaldus, prophets, representatives of the donator families. Similar five-aisled arrangement features the sacrament house of St. Jakob in Rothenburg ob der Tauber dated back to the last decade of the 14th century, which has two strong horizontal compartments as well (Figure 10) The main compositional and iconographical emphasis is on the central axis of the host-shrine with an entombment scene below and a depiction of the throne of Mercy above. The hierarchy of meanings is more accentuated by its strong vertical and horizontal division and by the size of figures than it is on the Nuremberg sacrament house.6

The central meaning of the program in Nuremberg is the presence and force of the Corpus Christi, which surpasses the narrative elements of the depictions.21 Christ of the Last Judgment shows us his wounds and the crucifixion refers to the sacrifice of Christ presented by the Holy Mass. The dead body of Christ in the entombment scene is presented us by the figures behind him (Figure 9) The holy women do not show the explicit gestures of lamentation. Instead of mourning expressions the central moment of the scene is the partly uncovered body of Christ itself, which is slightly turned to the spectator. As if lying body was pushed forward to the foreground to make the wound on the right side of Christ is seen. The uncovered consecrated host was the most important source of salvation, which finds an expression in the entombment scene and in all of the depictions in the main axes.

As with the “entombment scene” of the Nuremberg sacrament house, the Holy Sepulchre compositions are not a single scene of the passion. The depiction of the dead Christ lying in the tomb is not the same as in the entombment scene. The Holy Sepulchre compositions generally lack the figures of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea and the apostles; furthermore the mourning gestures of the women are also missing or not so explicit. On the stone monument in Freiburg in Breisgau, the women seem to be aware of the body lying in the tomb, thus the composition cannot be regarded as a scene of holy women at the empty tomb on Easter morning either. The figure standing behind the dead body and the figure of the dead Christ himself are in the same time and space. The death and the resurrection of Christ are represented at the same time. The Holy Sepulchre-composition seems to have been able to adapt itself to all the rituals performed around it. It was the place and the instrument of the commemoration of Christ’s death and entombment on Good Friday. The tree standing women at the tomb and Christ can be referred to the events of the entombment and lamentation.22 During the forty-hour period of the death the tomb was presumably watched over, psalms were sung and lay people would have had the opportunity to visit the tomb to pay veneration. Depictions of sleeping guards on the sarcophagus and the image of the dead Christ allude to this period. The women at the tomb can be interpreted as the Holy Women at the empty tomb on Easter morning. In spite of the presence of the lying body, the composition could refer to the resurrection during the Easter ceremonies, because the consecrated host had already been elevated. Therefore the sepulchre could serve as scenery during the “visitatio sepulchri”, a dramatic representation of the arrival of the holy women at the tomb.

In contrast to the entombment scene in Nuremberg sacrament house the standing female figures of the Holy Sepulchre in Freiburg are more significant than the dead body. Christ is simply lying in the tomb without his striking presentation. The distinction is not only derived from the polysemic character of the Freiburg composition, but from its different function as well. Both were used for the housing of the sacrament but for different purposes, which is manifested by the relation between depiction of the dead body and sacrament-shrine. The receptacle of the consecrated host visually has a lesser importance than in Nuremberg. The Eucharist was placed inside the sepulchre, that is, it was part of the image. The placement of the sacrament can be different at each Holy Sepulchres, but it was regularly placed in close connection with the figure of Christ, as we can see in the former Benedictine abbey of Gengenbach (Figure 13) or in the cathedral of Breisach (Figure 14), but we hardly can speak about a visual expression of the veneration of the sacrament. A reversed relation between the sacrament shrine and depictions can be seen in Nuremberg. The shrine of the sacrament occupies the Centrum surrounded by depictions, which are subordinate to the sacrament and interpret its significance. The difference between the two liturgical furnishings and their visual languages can be more clarified by discussion of rituals.

20Weilandt G. Die Sebalduskirche. 2007. 106 p.

21Weilandt G. Die Sebalduskirche. 2007. 108 p.

22Boerner B. Bildwirkungen Die kommunikative Funktion mittelalterlicher Skulpturen. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag; 2008. 198 p.

The three offices at the sepulchre, depositio, elevation and visitation sepulchri, have been frequently considered extra-liturgical. Especially the visitatio, the dramatic representation of the arrival of the holy women at the tomb, has been regarded less a part of the official liturgy.23 The term extra-liturgical received from the discipline of liturgical history corresponds to the ideas of several medieval liturgiologists. Durandus in his Rationale divinorum officiorum wrote about the visitatio as follows: “Si qui autem habent versus de hac representatione compositos, licet non authenticos non improbamus”.24 He made a difference between authentic and non-authentic elements of the liturgy, but non-authentic elements are not disapproved. In semiotic respect Christoph Petersen distinguished between performance types according to sign-usage.25 The sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated during the Holy Mass, which is the most important source of salvation in the Christianity. Signs are not determined by the mimetic or narrative character, but they are coded liturgically.26 It does not represent or imitate the event of the Last Supper, but establishes the transsubstantiation. Bread and wine are really converted into Christ’s body and blood. The reference of the signs such as sounds, gestures, vestments, objects or the Sacrament itself is not obvious. The similarity of liturgical and historical sacrifices frequently cannot be perceived in reality, but only exists in imagination. Resemblances for the most part are constituted by hermeneutics.27 The medieval allegorical liturgical expositions transformed the signs of the mass into a representation form of Christ’s life and created a narrative coherence, however, the mass does not provide a history of Christ’s sacrifice.28 Medieval liturgical writers did not seek after a definite meaning of signs, since the relationship between signifier and signified is not evident.29

The Visitatio sepulchri, in other words Officium sepulchri, was performed during the lauds early in the morning, but it never belonged to the compulsory parts of the Roman Rite. As Christoph Petersen suggested, visitatio does not need an allegorical interpretation, since its function was the mimetic representation of the historical events of Easter morning.30 All the signs were coded theatrically.31 Moreover new signs were needed to create for the Visitatio sepulchri, which were arranged in a narrative coherence not only imaginary but in reality too.32 The “sepulchrum” is also a new sign. Johannes Beleth identified the sepulchrum as “quendam locum, ubi ymaginarium sepulchrum adaptatur.”33 It was a place, which imitated the tomb of Christ. According to Petersen, this place was not identical with the altar but it must have been an occasional construction.34 His conclusion seems to be right despite of the fact that some of the liturgical sources report about a sepulchrum, which was set-up on an altar. In the Prüfening manuscript mentioned above, the sepulchrum was not identical with the altar but the sarcophagus on it. The altar provided only the place for the sepulchre. Similar situation can be read in Narbonne ordinarium from about 1400: “levent cum filo pannum qui est super libros argenti super altare in figura sepulchri.”35 Some silver service-books were laid together on the altar.36 The sepulchrum frequently situated near the altar. According to the ordinarius of Zurich there was a coffer within a curtained enclosure behind the altar: ’sacerdotes predictam parvam crucem ponunt et signando claudunt in archam que intra testudinem retro altare martyrum candido velo circumpendente posita sepulchrum dominicum representat.’37 The phrasing as “in figura sepulchri” and “sepulchrum dominicum representat” refer to the mimetic character, which is the main feature, makes the sepulchre different from other liturgical furnishings as the altar and the sacrament house. The altar could be the place of the sepulchrum, but the altar and its surroundings were transformed before the beginning of the Easter season. From this point it is clearer, why the sepulchre needed a separate place. With the words of Petersen we should distinguish between liturgical-commemorative sign-usage and mimetic representation, accordingly signs can be coded allegorically or theatrically.7 Sepulchre is a figural representation of the burial place of Christ as well as the ritual around it. The three offices at the sepulchre, i.e. depositio, elevation and visitatio sepulchri, were intentionally connected by a narrative. The mass itself is not a figural representation, likewise the placing of the consecrated host into the tabernacle after the holy mass is not a representation of the entombment and there is no narrative coherence at all. It could get the allegorical meaning of the burial subsequently, but the sacrament house does not imitate or represent the tomb of Christ.

The difference in sign-usage seems to meet the observation that the sacrament houses and the Holy Sepulchres used for the depositio hostiae have completely different visual languages and structures in spite of their similar usage. The tabernacle is a liturgical furnishing with several depictions, which are subordinate to the sacrament and interpret its significance and provide a visual expression of the veneration of the sacrament. The Holy Sepulchre, being either a permanent stone monument or an occasional temporary structure at an altar, is a figural representation of Christ’s tomb. The sacrament and the small sacrament shrine in the sepulchre interpret the figures of Christ’s tomb and the dead body. The sacrament encouraged the spectators to see through the image and experience a higher religious truth and read the figures as signs instead of scene.8 Images had also different functions. The depictions of the Holy Sepulchre did not provide an allegorical meaning of the ritual, but they took part in the ritual around it. Both the design and the function have a mimetic character, which make it different from the other liturgical furnishings.

23Brooks NC. The Sepulchre of Christ. 1921. 47 p.

24Ibid.

25Petersen C. Ritual und Theater, Meßallegorese, Osterfeier und Osterspiel im Mittelalter. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 2004.

26Ibid. 17.

27Ibid. 25-26.

28Ibid. 30

29Ibid. 28.

30Ibid. 84.

31Ibid. 85.

32Ibid.

33Ibid, 85.

34Ibid.

35Brooks NC. The Sepulchre of Christ. 1921. 61 p.

36Chambers EK. The Medieval Stage. Oxford University Press. 1903;2:21.

37Liber ordinarius 1260, Zürich, Zentralbibliothek. ms. C 8b. 51b See: Brooks NC. The Sepulchre of Christ. 1921. 109 p.

The main objective of this examination is the function of the late medieval Holy Sepulchres with a figure of the Saviour built interior of the church buildings. One of the functions they fulfilled was during the liturgy of the Holy Week which had been getting more and more visual and theatricalised. On Good Friday the Holy Sepulchre served as a symbolic burial place for the figure of the dead Christ or the cross and possibly the consecrated host as well (depositio crucis, depositio hostie). On Easter day there was a corresponding ceremony in which the same objects were raised to symbolize the resurrection. Since it is almost impossible to find liturgical sources which can be assigned with complete certainty to a given church at a specific period, the exact use of an Easter sepulchre frequently remains obscure. Nevertheless, the purpose of this undertaking is to see how liturgical texts can support the endeavour to explain the special use of holy sepulchres and make their function clear. As a result of the examination it can be highlighted the features of Holy Sepulchre, which make it different from other liturgical furnishings of the churches. Both the design and the function have a mimetic character different from the liturgical-commemorative sign-usage of the Holy Mass.

None.

Author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Juhos. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.