Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

This work includes two parts. The first part is a theoretical approach to genealogy in the 21st century that offers a classification of genealogy as a complex social discipline and a branch of anthropology. Although many may believe that genealogy is a historical discipline, the 21st century development of genealogy completely corresponds to the main characteristics of anthropology. The revealed cultural and historical anthropology focuses on the role of studying context for complete genealogy research. Genealogy intersects with technology, as well, but it is also very close to art. On the whole, genealogy recreates a valuable culture that connects generations and people all over the world. The blooming of genetic genealogy allows people to find lineages to which they belong even if they have never known the identity of their parents. The second part of this work uses a case study to analyze the records about the earliest 19th-century Bulgarian immigrants in the US using ancestry.com for a scientific analysis and as a database with billions of vital records. The analysis of the data showed the research of the immigration in a given time span requires using as primary information not the passenger lists, but all possible vital records that contain direct and indirect information. The scientific analysis focused on the peculiarities in studying the 19th century immigration of Bulgarians in the US in particular, the incorrect documentation of the place of origin (Bulgaria instead of Bavaria or Belgium, for instance) and other challenging research problems. It was interesting in the course of the analysis of Massachusetts data about Bulgarians to recognize that American vital records may include some early cases of adoption of Bulgarian children. This discovery requires more detailed critical analysis.

Genealogy is one of the fastest-progressing social complex disciplines of the 21st century. The paradox of the 20th century is that the university-level academic environment did not embrace genealogy as a leading social discipline and therefore it has been evolving mostly outside of the university context. In the early 21st century, genealogy was established as a branch of anthropology,1 although this position still needs to be represented in university academic programs and textbooks. The uniqueness of genealogy as a social research discipline is its ability to pair science and popular culture and to enable vast segments of the population to contribute to genealogical information. Countless individuals from all over the world who research their own family history together, professional researchers including traditional and genetic genealogists and writers of family history essentially collaborate to advance genealogy as a top social discipline.

This work expands the open-ended classification of 21st-century genealogy offered previously2 and focuses on a case study related to the earliest Bulgarian immigration to the US in the late 19th century, as documented at ancestry.com.

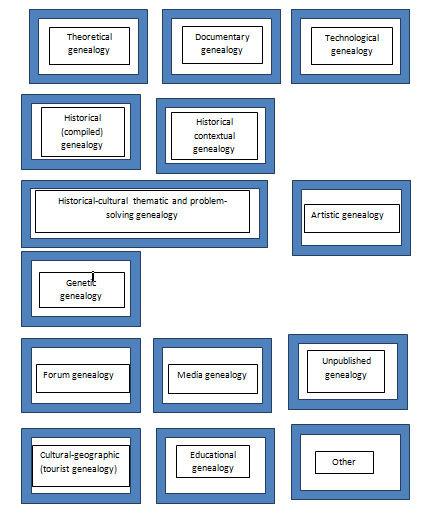

The open-ended classification of genealogy2 (Figure 1) focuses on defining categories that typically cross and overlap.

Theoretical genealogy

The scope of theoretical genealogy is the revelation of the theoretical aspects of empirical research as standards and peculiarities, development of the methods of research, technological provision and means of communication. One example is the author’s article on genealogy as a branch of anthropology1 which filled an important gap in genealogy: its attribution to a higher academic category to allow genealogy’s transformation from a recreational-based (pursued by a hobbyist or certified hobbyist) discipline into a high-profile, academically complex discipline requiring PhD-level (and higher) achievements and frameworks. Disinterest from university anthropologists in genealogy has created a professional gap that needs to be filled with highly qualified experts on campus.

The instructional branch is popular in theoretical genealogy and features guides for different genealogical research and information about how to find ancestors from a specific homeland (Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, etc.). Resources of this type make extremely useful textbooks. Another typical guide is determining the location of different types of records.3,4 More recently, guides to genealogical search engines and digital archives are particularly valuable in assisting in the research of all those interested in genealogy.5 A new level of genealogical theory, however, would be the search for theories to create the roadmap for thematic research, including finding homelands, biological parents, etc. For example, numerous studies on European immigration to the United States make it possible to identify several aspects of genealogical migration research, which, in many cases, can be a shortcut to the most significant discoveries in genealogy in step-by-step research:

Discovering the ancestral sequence of generations based on marriage and/or death certificates in civil and/or church records.

Documentary genealogy

This category encompasses all documentary sources for genealogy, including digital archives, historical archives, museum finds, archives and expositions with genealogical documents, etc. Figure 2 represents one of the most popular types of records for American genealogy the US Federal Census,6 while the primary type of record that reveals immigration information is the passport application (Figure 3). Documentary genealogy includes published original records (vital and cemetery records, church sources, censuses and tax lists, probate records, land records, court and legal records, military sources, immigration sources and documentary sources)7,8 and compiled records (family histories and genealogies, county and local histories, biographies, genealogical periodicals and medieval genealogy). In this classification, published original records (along with filmed, archived and/or digitized published records) belong to documentary genealogy, while compiled records belong to historical genealogy.

Technological genealogy

The technical provision of genealogy comprises specialized software and Internet servers. DNA analyses require professional laboratories. Artistic genealogy also requires programs and specific technology, along with artists-experts in genealogy projects. Published guides like, for instance, the official guide to Family Tree Maker complement the software.9 An annual Roots Tech conference in Salt Lake City allows attendees to discuss the newest technology in the field of genealogy.

Historical (compiled) genealogy

Historical genealogy relies largely on family studies, which result in family trees, pedigrees and family stories and memories in other words, the core of genealogy. The category includes two main subcategories online sources and published hard copies. Ancestry.com, familysearch.org and many other smaller web servers offer free space for family trees. The Family History Library in Salt Lake City has one of the richest library collections of family histories, although most of the contemporary books are available at amazon.com.10

Historical contextual genealogy

This category encompasses the study of the historical context of the micro- and macro-genealogical structures (family, lineages, etc.). A particular direction of genealogical research is how historical events and collected evidence affect individual family histories, genealogy-related social groups, national destiny and global population. In general, the study of historical context means researching the impact of historical events on ancestors throughout various time periods.

The category also includes thematic research, which generates historical compiled books as a secondary source for family history. The biographical dictionary by Martha W Cartney11 about Virginia immigrants and adventurers from 1607 to 1635 is an example of such a study. Another example is the published research on colonial and medieval families by Douglass Richardson.12 The case study reported below also belongs to the historical thematic compiled genealogy category.

Genetic genealogy

Genetic genealogy connects individuals and families based on DNA analysis. It is especially important in cases of adoption and in the absence of written sources, or when encountering conflicting information between the records and the written information (see the case study below as an example). This category incorporates different branches: DNA samples and the differences between the companies that offer DNA sample kits, DNA labs for genealogy purposes, servers for interpretation of the data, genetic genealogists and publications13 23 & Me and Family Tree DNA currently offer the most popular DNA sample kits.

Artistic genealogy

This is a multi-aspect category which embraces an artistic shaping of family trees or family sheets and software used independently or through Web servers; design of books and magazines; artistic photography; works of art (portraits, genealogical topics, landscapes of ancestral homes, home movies, etc.); works of the ancestors listed in pedigrees; and genealogical media servers or individual pages.14 Both photos (Figure 4) and signatures (Figure 5) are essential for genealogy research with artistic components. In fact, the personal style of signature and handwriting or the style of hair and clothes may, in some cases, become primary indicators in a specific genealogy research project.

Media genealogy

Media genealogy includes messages (sad news, reunions of lineages, etc.), publications (articles, specialized periodicals or books), documentaries, feature films, reflections, interviews and other forms of communication of genealogy in the media. Genealogy is one of the most popular fields of interest in social media worldwide.

Cultural-geographical (tourism) genealogy

This category encompasses individual visits to ancestral places or the organization of tours during which the cultural tourists visit places of interest to their own ancestors or of whole migration social/ethnic groups.

Creative narrative genealogy

This category includes narrative family histories published as monographs, articles, or online sites.

Forum genealogy

Forums are one of the most popular methods of communication in genealogy, from discussion walls on the Internet and public groups on Facebook to various large and small scientific and educational conferences and symposia.

The National Genealogical Society, a non-profit organization, has annual meetings in the US with sessions offered online. It was founded in 1903 and remains a forum where genealogists of all levels are able to exchange information. Other organizations in the US include the Federation of Genealogical Societies, the Association of Professional Genealogists, the International Society of Genetic Genealogy, etc. Similar organizations exist in Europe; they typically have low budgets and rely on volunteer activity. One good example is the Bulgarian Genealogy Federation; its president, Antoaneta Zapryanova, was honored in 2017 with the “Georgi Markov for Humanity Award” for her enthusiastic and tireless efforts to maintain high academic standards for genealogy research in Bulgaria.

Beyond the meetings of non-profit organizations, the development of international collaboration in genealogy is also critically important in the early 21st century. In late July 2017, the International Germanic Genealogy Conference was held for the first time in Minneapolis, Minnesota, hosted by the local Germanic Genealogy Society. A third example of forum-based genealogy is the numerous genealogical groups on Facebook in different languages which represent important aspects of the cultural memory of the 21st-century global society.

Educational genealogy

Educational genealogy is an extremely important category for enculturation the process by which a person learns the requirements of culture and acquires the values and behaviors that are appropriate or necessary for this culture and for the development of his or her own personal culture of understanding and behavior. It is also essential for the socialization of younger generations or the process by which individuals become members of society. The study of genealogy in school, development of a genealogy profile in the higher education departments of anthropology, enrollment in individual courses and visits to training centers and family history libraries with learning centers are valuable opportunities for enculturation and socialization. The world's largest family history library is in Salt Lake City, Utah, with branches throughout the world,10 while ancestry.com is the world’s largest digital archive for family research and for scientific research based on vital records and family sources.

Setting

This case study will reveal peculiarities in the records about Bulgarian immigration in the US all of which are available at ancestry.com. It will demonstrate how the ancestry.com search engine and database, containing billions of historical records, can be used for scientific problem-oriented research.

Two versions of the story exist regarding the emergence of the earliest Bulgarians in the US.15 According to one version, the first Bulgarians arrived in the US as early as the end of the 17th century, when about twenty Bulgarians arrived on a Venetian trade ship. The second legendary version relates to a group of soldiers recruited by French diplomats for the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). According to Y Vasilev,15 some of those early Bulgarians who arrived in the US sent letters to Bulgaria, causing between 2,800 and 3,200 additional Bulgarians to migrate to the US in the second half of the 18th century. Missing or unavailable evidence makes it impossible to reject these legends. Genetic genealogy and future discoveries may, in time, result in the revelation of very deep roots of the Bulgarian ethnic presence in the US.

From the perspective of documentary genealogy, Bulgarians discovered or rediscovered the US as their second homeland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.41,16−20 The number of immigrants before 1900 was probably between one thousand and three thousand, including both Bulgarians who initially lived in other European countries (or elsewhere in the Turkish Empire outside the ethnical core of Bulgaria) and those who came directly from Bulgaria. Migration was gradual in the early 20th century until 1907, when immigrants numbered between 12,000 and 20,000 people. In 1908, due to the special Bulgarian protective law, the number dropped to about one thousand immigrants. In the next decade, the migration number fluctuated, with a peak in the period from 1910 to 1914 (about 3,000 to 7,000) and dropping to fewer than 100 in 1918, according to data at ancestry.com. Between 1919 and 1989, the number of Bulgarian immigrants was fewer than 1,000 yearly (fewer than 100 in some years during the Cold War).

The 2000 US Federal Census documented 55,489 American citizens and residents with Bulgarian ancestry (cp. 1990-8,579),21 although that number has now grown to about 250,000, according to the Bulgarian Embassy. The 2006 American Community Survey provides a figure of 92,841 (±8,405).22The precise statistical record of the immigration of Bulgarians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries faces many difficulties due to the method of clustering several countries in the official statistics of the US.23 In addition, illegal immigrants presumably entered the country to avoid the Ellis Island port, where many immigrants were turned back.18 Last but not least, the absence of documentation of the emigrants from the US, including Bulgarians who went back to their homeland, makes researching the migration dynamics of Eastern Europeans one of the most complicated research problems.

Since 1990, Bulgaria has been one of the nations with the highest migration to destinations all over the world. More than two million Bulgarians immigrated to new homes around the globe, including thousands of Bulgarians who arrived with Green Cards in different states of the US. The dynamic picture of the migration of Bulgarians in the US before 1989, as described above, is based on data at ancestry.com. This is a searchable document database that uses extracted data from primary sources (US Federal Censuses, voting records, immigration and military documents, etc.). Although used primarily for family history research, the ancestry.com search engine is extremely valuable for scientific, historical and anthropological research. Dates, keywords and locations become the main searchable data in scientific historical research instead of a person’s name.

The first documented Bulgarian who came to the US seems to be Ivan Dobrovski,24 possibly about 1848. Iliya Yovchev, a journalist who arrived in the US to study, wrote that about 10 Bulgarians lived in the US in the 1860s and 1870s, including Hristo Sariev. One Bulgarian was killed in the Civil War (1861-1865). In this pioneer period before 1900, students some of them young Bulgarians who were attracted by American Protestant missionaries arrived in the US with recommendations, in particular from Dr. Long and Dr. Ring (Constantinople Tsarigrad, Turkey). The list of Bularians includes Andrej Sultanov, Racho Gospodinov andrej Tsanov, Yordan Ikonomov, Todor Boyanov, Trajko Teslichkov, Stefan Tomov, Hristo Balabanov [see below], Dimitur Kalinov, Vasil Bogozki, Rashko Gerganov, etc.24 Several new names will be added below, documented solidly in American records.10

Discoveries

1880 US federal census: com is the primary source for studying the problem of the earliest Bulgarian immigrants to the US in the late 19th century based on American documents. Using the ancestry.com database for research presents many peculiarities. The precise conclusion requires an analysis of every document, although using the figures from the search paints, in many cases, a very impressive picture for comparative analyses and further in-depth research.

The detailed, in-depth nature of the specific records allows researchers to recognize patterns of mistakes that exist in the primary records. Typical examples are passenger lists and census records. They have characteristics of documents with primary information, but in reality, the information can be misleading. One typical documentation problem in regard to the ethnicity and nationality of European immigrants appears in the case of Bulgaria and Bulgarians in particular. Bulgaria, along with Bavaria (Germany), Belgium and even Hungary, were used interchangeably, since the clerks who recorded this data might have written “Bulgaria” not knowing that the respondents meant “Bavaria,” for instance. The 1880 US Federal Census at ancestry.com25 demonstrates many instances in which Bulgaria was used to mean Bavaria. More than 50 individuals with German names (probably Bavarians) were listed as Bulgarians (born in Bulgaria or with one or both parents born in Bulgaria). In fact, only six records pertaining to Bulgarian immigrants in the 1880 US Federal Census are certain and confirmed and they are among the earliest recorded Bulgarians in American censuses (Table 1).

US census |

Name |

Born |

Residence |

Occupation |

1880 |

Jno (Ivan) P. Balabanoff |

Abt. 1857 Bulgaria |

1880 - Kirkland, Oneida, New York |

At school |

1880 |

Christo P. Balabanoff |

Abt. 1859 Bulgaria |

1880 - Kirkland, Oneida, New York |

At school |

1880 |

Marin Gregoroff |

abt. 1858 Bulgaria |

1880 - Albion, Calhoun, Michigan |

At school |

1880 |

George Popoff |

abt. 1850 Bulgaria |

1880 – Olivet, Eaton, Michigan |

A student |

1880 |

John Shopoff |

Abt. 1860 Bulgaria |

1880 - Nelson, Portage, Ohio |

Student and hired man |

1880 |

George Vulcheff |

Abt.1854 Bulgaria |

1880 - Princeton, Mercer, NJ |

Attending school |

Table 1 Earliest recorded 19th century Bulgarian immigrants in the 1880 US Federal Census

Therefore, all other immigrants born in Bulgaria or with parents born in Bulgaria require detailed analysis. Several examples below demonstrate the development of explanatory hypotheses based on the available information the name, gender, age, occupation and context (the nationality and origin of those registered on the same page in the census).

The details regarding 30-year-old Timothy Blugler are a case in point. Born in Bulgaria, according to the 1880 US Federal Census, he lived in Elbridge, Onondaga County, New York.25 He was a cigar maker and a boarder in a family in which all members were born in New York, NY. His status as a boarder and the fact that no other documents exist for this person for the time being increase the possibility that Blugler was a Bulgarian who changed his name. If he appears on a family tree elsewhere, genetic genealogy may help to determine whether he was indeed of Bulgarian origin.

John Somer is also a possible Bulgarian despite his age (he was 46 in 1880) and non-Bulgarian name. However, a correction on the census changed his place of birth first written as “Bugaria,” to Bulgaria.25

Paul Blumenan, age 27, also claimed he was born in Bulgaria, according to the 1880 US Federal Census.25 In 1880, he lived in St. Louis, St. Louis County, Missouri (ED 4, page 23). The census reports that his parents were also born in Bulgaria. Blumenan was single and worked as a waiter in a restaurant. He lived as a lodger in a family whose origin was Prussia. Here is a typical case of a person with a German name documented as having been born in Bulgaria in the 1880 US Federal Census. The fact that he lives with a family from Prussia serves as the basis of an argument that perhaps the clerk who took the data from the head of the household (Conradus Schofer, age 35, from Prussia) did not understand Blumenan’s origin. Therefore, since Bavaria was not an independent country, Blumenan’s birthplace was listed as the country of Bulgaria. This is probably the explanation for most of the “Bulgarians” with German names in the 1880 US Federal Census. They were actually born in Bavaria, or one or both of their parents were from there. Other similar cases include those of B. Daeh from Shaler, Allegheny County, PA; Henry Deckard from Union, Pulaski County, MO; Catherine Hahn and Christian Guth from Cazenovia, Woodford County, Ill; and William and Paulina Rosenthal from New York City, New York County, NY, etc.

The records on ancestry.com include cases when, even if Bavaria was listed as the homeland in the census, the handwriting would be deciphered as Bulgaria (e.g. Margareta Cook, from Philadelphia, PA; Louisa Hess from Caledonia, Racine County, WI). The other typical deciphering error is Bulgaria instead of Belgium e.g., Barbara Falkenrath.25

Peter Burns age 44, single and a sailor was a boarder in a facility for boarders in Enumeration District 1 in San Francisco, CA.25 However, all other neighboring boarders were from Ireland, England, Norway, or Sweden. From a contextual analysis of that community, it can be inferred that Bulgaria was mistakenly written in the census as Burns’s homeland instead of Belgium.

Documented information in the 1880 US Federal Census about James Clark is also intriguing. He was an 18-year-old student, born in Bulgaria, whose parents were born in Massachusetts. 25 All others listed on the page except one (who was Irish) were born in the US Based on the peculiarities of Bulgarian immigration to the US, the first hypothesis is that James Clark was perhaps a Bulgarian student who changed his name and his parents were incorrectly listed as having been born in Massachusetts. However, there is another case of a teenager born in Bulgaria: William P Clark, who was only 14, living in the household of 58-year-old Jonathan Sane (whose wife, Sarah, was 52 years old), a merchant25 with three sons. The census contains no description of the relationship of William to the head of the household. William was born in Bulgaria, but his parents were from Massachusetts. William’s young age and the repetition of parents born in Massachusetts may document cases of adoption of Bulgarians by Americans in the late 19th century, which may provide evidence of the earliest documented cases of adoptions by Americans.

George H Emery is also a subject of particular scientific interest. George is a very popular Bulgarian name. He was 34 years old in 1880 (born about 1846 in Ohio) and his residence was Liberty, Adams County, Ohio-ED 7, page No. 8.25 His father was listed as Bulgarian, but he also lived with his grandmother, Barbara Munich, from Württemberg. Therefore, it is likely that a mistake was made and Bulgaria was listed instead of Bavaria. Unfortunately, it is impossible to determine the relatives of “Elijah Bulgarian,” documented in the 1870 US Federal Census.6 He was a 20-year-old laborer who lived in Boonville, Oneida County, NY.6 It can be assumed that he was indeed a Bulgarian (Figure 1).

Other vital records for the earliest Bulgarian immigrants: One successful method of finding earlier Bulgarian immigrants is using all the collection tools available on ancestry.com and specifying the years of arrival (1870±10) with keyword “Bulgaria.” The search returns 512 results, but some records are repeated and the entries include some of the mistakes discussed above. In the 1920 US Federal Census, Ivan P Balabanov, who was also documented in the 1880 US Federal Census,26 lived in Tacoma Ward 8, Pierce County, Washington and worked as a physician. He was married to Edith, a nurse born in New York. They lived with Edith’s sister, Ethel W Brewett, who was divorced.26 In Bulgarian popular literature, Ivan’s brother, Hristo Balabanov, is named the first Bulgarian doctor in the US.24 As Table 1 shows, the two studied together.

The passport application of Ivan P Balabanov (Figures 2-4) provides important additional data about the late 19th-century Bulgarian immigrants in the US who successfully continued their lives as Bulgarian Americans. Balabanov was from Kazanluk, Bulgaria, born on 19 March 1855. His father was Hadji Radi P. Balabanov, who was born in Bulgaria and died in 1861. According to this document (Figure 2), Ivan P Balabanov arrived on 28 December 1876.27 Along with the signature, the flip side of the application includes photos of Dr. Ivan P Balabanov and his wife, Edith (Figure 3). The passport application combines evidence from different branches of genealogy documentary, family history, artistic genealogy, etc. The signature of Dr. Ivan Balabanov in this document is among the earliest documented signatures of a Bulgarian-born doctor in the US (Figure 4).

A common and successful strategy of these early Bulgarian immigrants was to marry an American citizen or a person of another (non-Bulgarian) nationality. Since the earliest immigrants were either students or laborers, they either were not married or were not able to invite their wives and other members of their families to immigrate with them because of low incomes. For this reason, it was not until the late 20th century that married couples (both Bulgarians) became a more distributed type of immigrant throughout the US. Ivan Mishov (born about 1857) was a Bulgarian-born American enumerated in the 1920 US Federal Census who arrived in 1878.26 Unfortunately, the years of immigration in the census records are not always reliable and require additional evidence. In this case study, the 1910 US Federal Census28 repeats the same year of immigration 1878. Ivan Mishov was also a physician and a person of dignified status like Dr. Ivan Balabanov. He studied medicine at Rush Medical School in Chicago, Ill., according to an obituary attached to his memorial # 110214543 at Find a Grave.29 Like many other Bulgarian immigrants, Dr. Mishov married an American, Laura Ransh, whose parents were of German origin.26 Find a Grave rarely provides the birthplace of the earliest European immigrants, but using combined data from different genealogical sources helps to paint a more detailed picture of 19th century Bulgarian immigrants in the US.

The brother of Ivan P. Balabanov, Dr. Hristo P. Balabanov is well documented. He was born on 15 December 1858, according to his passport application27 and died on 4 August 1943. He was married to Ella, who was born in New York.27 Another very important and successful research strategy is verifying the extracted information at ancestry.com with the original document, if it is available. In some cases, technical errors are obvious even in the extracted data. For instance, Louis Angeloff (with a Bulgarian last name) cannot be born about 1886 if he arrived about 1863.30 In other cases, the errors may not be as easy to recognize.

The examples above show that there are important data for Bulgarian immigrants who arrived before 1880 in the later US Federal Censuses, not in the 1880 US Federal Census. However, the data require a critical analysis and cross-referencing of information in different types of records, including World War I Draft Registration Cards, death certificates, Find a Grave, passport applications, etc.

This work includes two parts. The first part is a theoretical approach to genealogy in the 21st century that offers a classification of genealogy as a complex social discipline and a branch of anthropology. Genealogy intersects with technology, as well, but it is also very close to art. Overall, genealogy recreates a valuable culture that connects generations and people all over the world. Genetic genealogy allows people to find lineages to which they belong even if they have never known the identity of their parents.

The second part of this work uses a case study to analyze the records about the earliest 19th-century Bulgarian immigrants in the US using ancestry.com for a scientific analysis and as a database with billions of vital records. The analysis of the data showed the research on immigration in a given timespan requires using as primary information not the passenger lists, but all possible vital records that contain direct and indirect information. The scientific analysis focused on the peculiarities in studying the 19th-century immigration of Bulgarians in the US in particular, on the incorrect documentation of the place of origin (Bulgaria instead of Bavaria or Belgium, for instance) and on the names of places of parents’ origin. It was intriguing, in the course of the analysis of Massachusetts data about Bulgarians, to recognize that American vital records may include some early cases of adoption of Bulgarian children. This discovery requires more detailed critical analysis.

In searching early immigrants from Eastern Europe, the best strategies are:

The analyzed data in the research added new arguments to the previously outlined characteristics of early Bulgarian immigration in the US and offer a research map for filling the gap of detailed characteristics of early Bulgarian immigration based on vital records. It clearly showed that immigration records such as passenger lists are not reliable records for the earliest Bulgarian immigrants in the US in the late 19th century, while other vital records (census records, passport applications, Find a Grave entries, World War I draft registration cards, etc.) require detailed critical analyses.

Last but not least, researching 19th-century Bulgarian immigrants shows the importance of the results of genetic genealogy not only for family history, but also for answering key questions about ethnicity and origin in the context of immigration problems.31−34

It was extremely sad for me to learn, while searching for the newest evidence about the early Bulgarian immigration in the US online, that Dr. Ivan Gadzhev, my best friend in the US, passed away on May 20, 2017. He was an exceedingly kind person who made a fundamental contribution to the study of Bulgarian immigration in the US and to keeping the Bulgarian spirit strong in all new Bulgarian immigrants in the US He was honored posthumously with the “2017 Georgi Markov Award for Humanity” (June 12, 2017, in Sofia, Bulgaria).

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.