Journal of

eISSN: 2374-6947

Commentary Volume 1 Issue 4

School of Science and Medicine, University of Buckingham, UK

Correspondence: John C Clapham, School of Science and Medicine, University of Buckingham, Hunter Street, Buckingham, MK18 1EG, UK, Tel +44(0) 7920 845072

Received: July 09, 2014 | Published: August 21, 2014

Citation: Clapham JC. Type 2 diabetes: prospects for our grandchildren?. J Diabetes Metab Disord Control. 2014;1(4):93-94. DOI: 10.15406/jdmdc.2014.01.00019

In incidence of diabetes is rising inexorably yet drug treatment has essentially remained the same for decades now. Given the history of diabetes drug discovery over the last half century what are the prospects for new drug classes in the future? Although major improvements in the management of diabetes in well developed and well funded healthcare systems have been seen in recent years, the incidence of diabetes is rising at an alarming rate, particularly in countries with less developed healthcare systems. Addressing this issue is a major challenge for the future.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, global, burden, medicine

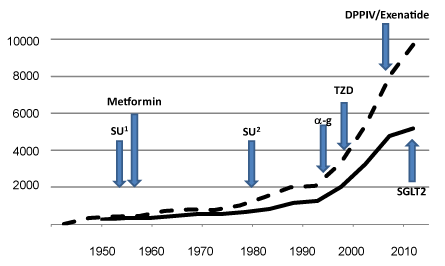

SU, sulphonylureas; a-g, a-glucosidase inhibitors; TZD, thiazolidinedione; DPPIV, dipeptidyl peptidase iv inhibitors; SGLT, sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

I recently attended a lecture on a major diabetes study currently ongoing in England. In the questions session the speaker said that the results of the study may result in better diabetes treatments for our grandchildren. That got me thinking. If you were diagnosed with type 2diabetes in, say, 1960, it was very likely that your medicine was metformin, by then on the market for 5years. If that persons grandchild was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes today the first drug treatment they are likely to get would be....metformin! So what are the prospects for our grandchildren then?

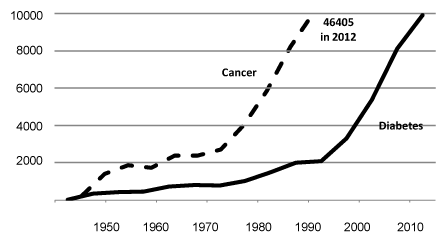

There is no denying the ever increasing effort applied to diabetes research. This effort can be very crudely quantified by searching PubMed for all articles containing the word “diabetes” in the article title (Figure 1). This shows a steady rise in the number of research articles with a marked upturn occurring from the mid 1990s. If you do the same for “cancer” the numbers are around 20times greater for each year searched. There seems to be clear benefit to this research effort, at least in affluent societies, with improvements both in cancer survival rates and mortality as a result of diabetes. For example, increases in the quality of health provision and monitoring seem to have reduced mortality of type 2 diabetes in Denmark,1 Iceland2 and Germany.3 Despite this, the serious issue facing us today is still the ever increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes worldwide; countries that cannot afford the luxuries of expensive care programmes are very worried by what they perceive as a continuation in rising mortality of diabetes.4

Even in the developed economies, type 2 diabetes treatments are causing huge strains on existing health service provision and expenditure. The charity, Diabetes UK, estimates that £10bn was spent on type 2 diabetes in 2010 with hospitalisation consuming around 80% of that money5 and that in the UK some 700 patients are newly diagnosed with diabetes every day.6 Costs are anticipated to rise to a staggering £16.9bn by 2035. In the rest of the world there is predicted to be 366million people with diabetes by 2030.7 The largest increases will occur in economies that will struggle to provide the type of care that northern Europe might enjoy. In the absence of a miracle lifestyle programme, safe, effective and economical medicines must the answer to prevent even advanced healthcare systems from being overwhelmed; the very effective “cure” of Roux-on-Y bariatric surgery8 cannot be deployed to millions of people.

Since 1955, 7 classes of drugs for type 2 diabetes have made it to the market as therapies; the sulphonylureas, biguanides, α-glucosidease inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, GLP-1s, DPPIV inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors (Figure 2). Of these, arguably the most effective class for ameliorating insulin resistance were the thiazolidinediones, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone; however, rosiglitazone was withdrawn from the market based on scares around cardiovascular safety. This decision has since been reversed and these drugs can be used again.

Is this a big enough armoury to tackle the growing problem? Indeed, metformin itself could be argued to fit the bill as a relatively safe, effective and certainly economic medicine. Type 2diabetes is a progressive disease, even with intensive treatment the disease will eventually win for the vast majority.

Asking the question, “what are the prospects for our grandchildren?” again, it might yield a rather cynical answer of “not great if the past 60years predicts the next”.

I don’t believe this. There has been plenty of high quality research, especially in more recent times, which I am sure will find its way into this journal in the future. We also have a more tools in the toolbox in terms of therapy compared to back then. Today, we are not bound by the paradigm of being dependent on inventing and developing small molecule therapies. In my experience these have shown themselves to been notoriously hard to develop for chronic diseases. We now have antibody and peptide therapeutics, which open up a much broader accessible space. If we take one protein therapeutic, insulin look at the improvements in that single protein therapeutic over the past decade or so. Furthermore, antibodies can be combined with small molecules and peptides to cover even more space. There is also a reawakening of interest in drugs from plants (indeed metformin is from French Lilac) which could be a very attractive proposition for the emerging economies where tens of millions of people will require treatment.

However, the likelihood of a “cure” by drug intervention is extremely challenging and probably very low. New drugs must get better at improving symptoms and quality of life which, if it translates to a large reduction in hospitalisation cases, then there will be a prospect of easing the burden.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2014 Clapham. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.