Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

1Dermatologist, professor of the post-graduation course of dermatology, in Policlínica Geral do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil

2Dermatology resident in Policlínica Geral do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil

Correspondence: Paula Periquito Cosenza, Dermatologist, professor of the post-graduation course of dermatology, in Policlínica Geral do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, Tel +5521999993912

Received: February 08, 2025 | Published: February 20, 2025

Citation: Periquito-Cosenza P, Periquito AFS. Thread master codes: Safe, effective and reproducible facial repositioning technique with PDO threads. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2025;9(1):11-17. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2025.09.00283

Background: Facial treatments with lifting threads are one of the non-surgical options increasingly requested in dermatology and plastic surgery offices. Despite, the practice techniques still lack systematization both to achieve more satisfactory results and to prevent adverse events. Most of the available publications provide little or no basis regarding the mechanics and physics of the aging process.

Objective: In this study, we bring our experience of more than 4 years using PDO threads for repositioning ptosis of the facial subcutaneous tissues that occurs during the aging process, in a safe, reproducible and effective technique. All techniques employed are based on the physical, mechanical and biological characteristics of PDO threads, as well as the aging process and anatomical features of the human face.

Materials and methods: Eighty-five patients underwent facial repositioning treatment with cog threads, whether barbed or molding. The threads used were USP 3-0 to 0-2 and were chosen according to each patient indication.

Results: Most patients reported very satisfactory results, with minimal discomfort during the immediate post-treatment period. Among all treated patients, no cases of thread migration or breakage were observed, with only one instance of a pyogenic granuloma forming at one thread entry point.

Conclusion: The vector technique with anchoring, using a knot posterior to the facial ligament line, for facial repositioning with PDO threads can be considered safe and effective for sagging treatment due to skin aging process. Technique is very predictable, with homogeneous results and fully reproducible by qualified professionals.

Keywords: face lifting, rejuvenation, lifting threads, traction threads, PDO threads, threads, non-surgical lifting, facial anti-aging force vector

Facial treatments with PDO threads have increasingly stood out in a context of minimally invasive procedures with reduced downtime and promising medium and long-term results in skin treatments. The current concept of managing aging process has gained more and more supporters, postponing or even preventing more complex surgical procedures. Despite this, the term facial thread lifting can generate unreal expectations for both patients and professionals regarding the results that can be achieved. We believe that cog PDO threads procedures should be understood as a continuous treatment for sagging, with results being built progressively. We propose the term facial repositioning which summarizes in a more concrete and objective way the true results that can be expected for thread treatments.

The skin aging process is multifactorial and encompasses changes in all structures of the face: skin, fat compartments, muscles, retention ligaments and bones1. One of the main aspects of this process is the reduction of collagen synthesis, which compromises not only the skin, but also deeper layers of the face.1,2 The complex process of resorption and consequent loss of bone volume occurring in the skull and facial bones results in a progressive loss of support for adjacent tissues, secondarily compromising the stability of already weakened retention ligaments.3 Also, gravity action and volumetric losses of superficial and deep fat compartments lead to progressive sliding of this tissue and consequent facial ptosis.2

Currently, there are still few objective scientific publications evaluating concrete and reproducible technical protocols for facial repositioning with PDO threads. Most of the available studies provide little or no basis regarding the mechanics and physics of the aging process.

We propose a new technique for cog PDO threads based on the physical and mechanical characteristics of both the threads and the aging process, as well as the anatomical and biological characteristics of the human face. The main target is to optimize results and create simple and reproducible, yet robust and effective protocols.

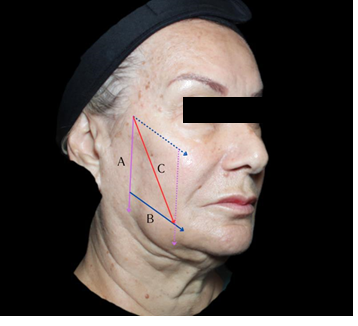

Using knowledge about Newton's parallelogram and triangular rules,4 Azevedo L described the main aging force vector5 (Figure 1 & Figure 2).

Figure 1 Triangular or Parallelogram Rule: A) Gravity force Vector; B) Flattened retained ligaments and fat pads vector; C) Facial aging vector.

Figure 2 By Newton’s third law, vector D is equal to vector C both in force and magnitude, but in the opposite direction.

According to Newton's third law, if every action is accompanied by a reaction of equal magnitude in the opposite direction, the main anti-aging force vector must act upward, in opposition to the gravitational force and backward, contrary to the rectification retaining ligaments force vector. According to the theory of Sines, described by Hipparchus of Nicaea (190 BC – 120 BC), the smaller the angle between two cables intended to support a given object, the lower the tension on them. Extrapolating this knowledge to the technique with PDO threads, the best angle to have the greatest traction capacity with the lowest tension, in order to avoid even their premature rupture, with consequent loss of tissue lifting and clinical results, is the 30º angle within 2 threads in the same vector. Furthermore, by using more traction vectors to support the same weight, we are able to further reduce the tension on each individual thread, optimizing results.

Some histological and anatomical aspects need to be considered. The SMAS located in the middle and lower thirds of the face can be divided into four distinct regions according to tissue characteristics of each region:6

Ligaments work as anchor points supporting the skin and fatty subcutaneous tissue. They are fixed to anchor points and their superficial extensions form the subcutaneous septa, which in turn permeate the facial fat compartments.7 The ligament line is an anatomical reference point that divides the face into anterior and posterior portions, with distinct characteristics.7 It is formed cephalad-caudally by temporal adhesion, lateral orbital thickening, zygomatic ligament, masseteric ligament and mandibular ligament8 (Figure 3 & Figure 4).

Figure 4 (A) Represents the ligament line, ending anteriorly to the jowl fat. (B) Represents the functional ligament line, which ends posteriorly to the jowl fat.

During aging process, a redundancy composed of the dermis and the subcutaneous fatty tissue overlying the mandibular ligament is formed and is named jowls. As this structure moves with facial expressions, it was proposed the concept functional ligament line of the face. It was described considering the dynamics of aging and facial expressions. In this approach, the lower anchoring point is the masseteric ligament7 (Figure 4 & Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cadavérica dissection of the left side of the face exposing the SMAS, superficial temporal fascia with the superficial temporal artery and the temporal fascia (upper face), and the parotid masseteric fascia (middle and low face). The blue arrows mark the masseteric ligaments on the anterior border of the masseter muscle (posteriorly to the mandibular ligament). The dashed pink line represents the functional ligament line (fLL).7 (Autorized by Eliandre Palermo, MD and Andre Braz, MD).

The zygomatic ligament is composed of dense fibers originated in the tragus and extending medially to the origin of zygomaticus major muscle and subsequently throughout the entire zygomatic arch.9 This skeletal-musculocutaneous ligament is considered the only true ligament within the facial ligament line,10 being the point of greatest anchorage support of the face. The temporal branch of facial nerve emerges from the upper limit of parotid gland, crossing zygomatic arch superiorly and then dividing into one to five distal branches that innervate the frontal, orbicularis and corrugator muscles.11 Throughout the entire path, it remains located below the superficial temporal fascia, crossing the zygomatic arch and the innominate fascia to reach the temporal area just below SMAS12 (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Throughout the entire path, the temporal branch of facial nerve remains located below the superficial temporal fascia, crossing the zygomatic arch and the innominate fascia to reach the temporal area just below SMAS.

In order to optimize the mechanical support of the threads, there must exist a strong anchoring point. From that point on we are able to achieve a great force of traction. Characteristically, this force needs to act in the opposite direction of tissue movement resulting from the aging force vector.5,12 Fixing the threads in the superficial temporal fascia area is considered effective.12 In our technique, we propose to anchor the threads in superficial temporal fascia, precisely where zygomatic ligament, the single true ligament of the facial ligament line is located.

The new technique has already been applied to 845 patients throughout many Brazilian cities during mentoring and patients from the private office located in Rio de Janeiro/Brazil, between the years 2020 and 2024. We used barbed or molded cog PDO threads from the brands available in Brazil. The choice between barbed or molded cogs was based on individual patient indications. As molded threads are designed to contain more robust cogs and a higher amount of polydioxanone in their composition, we believe they have a greater capacity for repositioning and supporting tissues.

For this study, 85 patients from Dr Paula Periquito's private office were included. The selected patients were between 40 and 79 years old, of both sexes and had a real indication for tissue repositioning, due to ptosis of subcutaneous fatty tissue. PDO threads must be inserted into superficial subcutaneous fat layer, wright above SMAS. Therefore, patients with scant subcutaneous tissue were not included in the study, due to the greater risk of complications. In those cases, maintaining a safe anatomical plane becomes technically challenging, and there is a scarce substrate for thread adhesion to the surrounding tissue. Patients with redundant dermal and epidermal tissue were also excluded, as PDO threads are not capable to retract those tissues.

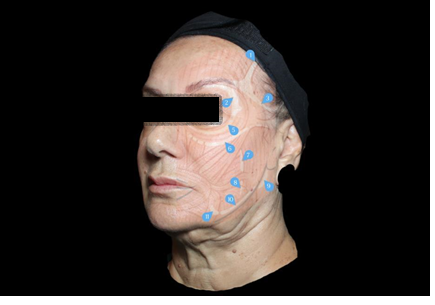

Safety limits: (Figure 7)

Figure 7 Safety Limits: Medial: 1cm from nasolabial fold

Figure 8 Although the temporal branch of the facial nerve crosses the zygomatic arch, it runs below the superficial temporal fascia not being adhered to skin during pinching maneuver.

The zygomatic arch was divided into 3 distinct regions: upper edge, midpoint and lower edge (Figure 9). The upper edge was chosen as the anchoring point for the first traction vector, the midpoint served as the origin of the intermediate vector, and the lower edge corresponded to the vectors related to the lower third of the face.

Figure 9 The zygomatic arch was divided into 3 distinct points: upper edge (blue dot); midpoint (orange dot) and lower edge (green dot).

Aging vector

During the aging process, we observe tissue movement resulting from the vertical action of gravity, but also related to the location and function of the retaining ligaments. The direction of the vectors should ideally be perpendicular to the protrusions formed by the wrinkles, maximizing the effect of tissue repositioning and the durability of the procedure13 (Figure 10).

Figure 10 (A) Shadow areas over the location of the ligaments. (B) Protrusions on the face caused by the displacement of the fat compartments, due to the lack of support due to ligament aging.

Vector ZMI

Target: Support of the middle third of the face, through malar region.

Origin: Upper edge of the zygomatic arch, 0.5cm away from hair implantation.

Direction of the threads: The first thread must be inserted close to the cutaneous zygomatic ligament, from lateral to medial, reaching up to 1cm away from the nasolabial fold, directed towards the canine fossae region. It must reach the upper skin protrusion remaining parallel to ligament aging force vector supporting the skin in a opposite direction. The second thread must be inserted into the same entry point, making an angle of 30º downwards (Figure 11).

Vector ZMII

Target: Reestablish facial volume in patients with evident depression in the subzygomatic arch.

Origin: Midpoint of the zygomatic arch, 0.5cm away from hair implantation.

Direction of the threads: The first thread must be inserted from lateral to medial, parallel and supporting the tissues with an opposite force to ligament aging force vector, directed to a medial point 1cm above the labial commissure, reaching the middle skin protrusion. The second thread must be inserted into the same entry point as the first, making an angle of 30º downwards (Figure 12).

Vector ZMIII

Target: Final repositioning of the jowls.

Origin: Lower edge of the zygomatic arch, 0.5cm away from hair implantation.

Direction of the threads: The first thread must be inserted from lateral to medial, parallel to and in such a way as to support the facial tissues with a force in an opposite direction to the main facial aging force vector, described by Azevedo, L5, reaching the lower skin protrusion. This thread will reach the mandibular septum, exactly where is the jowls. The second thread must be inserted into the same entry point as the first, making an angle of 30º upwards directed to the mandibular ligament (Figure 13).

Vector ZMIV

Target: Complement the support of the middle and lower thirds of the face in patients with a greater subcutaneous fatty layer volume.

Origin: Lower edge of zygomatic arch, next to the origin of ZMIII vector.

Direction of the threads: The first thread must be inserted from top to bottom, parallel to and in such a way as to support facial tissues with a force in the opposite direction to gravitational force vector. The second thread must be directed in order to make a 30˚ angle with the first (Figure 14).

Choosing vectors – Patient’s approach

Before starting each procedure, the patients were evaluated and diagnosed. According to individual indication, the vectors used in each treatment were designed. The minimum number of vectors performed was 2 per side, which corresponds to 4 threads per side and 8 threads in total. The maximum number of vectors performed was 4 per side, which corresponds to 8 threads per side and 16 threads in total. The combination of vectors used took into account the degree of shagging14 and the existence or not of subzygomatic depression (Figure 15 & Figure 16). Vector ZMIII was performed in all patients.

Procedures

Prior to the start, patients underwent asepsis and antisepsis with 2% degerming chlorhexidine and during the procedure 2% aqueous chlorhexidine. All procedures were performed under infiltrative local anesthesia containing pure 2% lidocaine with epinephrine vasoconstrictor (1:100,000), with a 30G needle, 0,5ml at each entry points. Along threads path, anesthesia was performed in a diluted solution 1:1 with saline, with the aid of a 22GX70mm cannula, 0,5ml each path. The disposable material used was always completely sterile, including surgical drapes, gloves, gauze, syringes, needles, cannulas and scissors. No prophylactic antibiotics were used post-procedure. The entry point for the threads that make up the traction vectors was made with a 16G needle. After introducing the 2 threads in the same entry point in order to form a force vector, they were tied in 2 single knots. The first knot was always buried into the skin before the second knot was made to keep them parallel one another, preventing subcutaneous nodulations.

The procedure was well tolerated, and patients reported minimal discomfort under infiltrative local anesthesia. The total average duration of the procedure since its programming, including anesthesia and the application of the threads itself, was 60 minutes. The discomfort reported during the first 15 days after the procedure was related to the inability to sleep in the lateral or prone position, in addition to restrictions in oral opening. Patients reported minor irregularities related to edema and tissue accommodation for a period of up to 4 weeks.

All patients (100%) reported attenuation of signs of aging in the first month after the procedure. The observation of the clinical effect associated with the maintenance of individual characteristics with real, but extremely natural results was unanimous (Figure 17).

As well as progressively better results in those patients who underwent more than one treatment session over the last 4 years (Figure 18).

A frequent observation was an improvement in the entire facial contour and also in cervical sagging with facial treatment alone, as in none of the cases analyzed were threads used in the neck (Figure 19).

Figure 18 Improvement in neck sagging and facial contour even with isolated treatment of the face. (A) Before and (B) 30 days after.

Furthermore, the global improvement in skin quality, in relevant aspects such as luminosity and fine static wrinkles, was also a reality. Patients were followed up after 30 and 240 days, with results maintained throughout the period in 94.11% of cases (Figure 20).

PDO threads have been used in cardiac surgery for decades and are hydrolyzed within a period of approximately 6 months.15 In addition to tissue repositioning, PDO threads improve texture, elasticity and stimulate neocollagenesis.16 Granulation tissue formation occurs around the PDO threads inserted into subcutaneous fatty layer. Through proliferation and aggregation of fibroblasts and multinucleated giant cells by TGF-ß16 signaling system, occurs the formation of fibrous connective tissue, which ends up reconnecting to the pre-existing tissue. Furthermore, there is an increase in the diameter of blood vessels in the treated region and a 20-fold increase in the concentration of type 1 and type 3 collagen. This entire process begins to be observed one month after the procedure.16

Associated with histological benefits, PDO threads are capable of repositioning subcutaneous fatty tissue that has suffered ptosis. It is considered that the main skin aging vector is affected by gravity associated with the loss of ligament stabilization due to bone reabsorption and tissue shagging. Therefore, any procedure that aims to reverse this process must exert an opposite force. The vast majority of techniques described currently, take little account of the physical, mechanical and biological aspects of aging process ant the thread’s material themselves. Since there are still no data about measuring the mechanical resistance of each thread individually, we can optimize the results of facial support following physical and mechanical criteria. In addition to complying with the main aging force vector, dividing the required traction force into smaller vectors that add up, reduces the individual tension on each thread, reducing the risk of premature breakage. Associated, the more the threads are used in a single treatment, the greater the amount of PDO applied, bringing the additional benefit of neocollagenesis.16

Promising clinical results are observed with the anchoring technique using knots between the threads that are positioned within the same vector.15 In floating technique, thread migration occurs in up to 8% of cases, also causing loss of clinical results.15 The resistance generated by the subcutaneous fatty tissue, associated with its positioning in the fixed portion of the face, posterior to the ligament line, restricts the movement of the threads that are interconnected by a knot. The difficulty of the procedure is small, but it requires technical training so that the knots can be correctly buried in the skin. Malpractice can lead to the formation of granulomatous lesions histopathologically compatible with pyogenic granulomas, at the entry point of the threads, as in the case we studied.

Schematizing both the criteria related to clinical indication and the best vectorization related to the individual diagnosis of each patient can contribute to more predictable and homogeneous results. No cases of thread migration or breakage were observed among patients undergoing the technique described in this article, raising the hypothesis that this is a promising technique with an impact on final results and reproducible with all PDO thread brands.

None.

Paula Periquito, MD is a medical speaker for the Brazilian company Innovapharma, which represents Croquis threads, in Brazil.

None.

©2025 Periquito-Cosenza, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.