Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Review Article Volume 9 Issue 4

1Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (FMABC), SP, Brazil

2Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de MG (FCMMG), MG, Brazil

3Department of Dermatology, Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), MT, Brazil

Correspondence: Luciana Gasques, Department of Dermatology, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, São Sebastião Avenue 3125, Quilombo, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil, Tel +55 (65) 981503366

Received: October 14, 2025 | Published: October 30, 2025

Citation: Cunha MG,Gasques L, Wanghon AF, et al. Retinacula cutis: anatomical insights, functional relevance, and implications in aging skin. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2025;9(4):115-117. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2025.09.00304

Until recently, the concept of retinacula cutis was largely overlooked in discussions of dermal anchoring mechanisms. It was widely believed that dermal support was maintained solely by the collagen fibers within the dermis. However, recent anatomical and histological studies have demonstrated that retinacula cutis, composed of fibrous septa traversing the subcutaneous fat layer, play a critical role in skin structural integrity, connecting the dermis to deeper fascial layers and contributing to three-dimensional soft tissue stability.

In addition to the dermal connective tissue matrix, collagen types I and III—abundant in the papillary and reticular dermis—confer tensile strength and resistance to mechanical stress. Elastin fibers, forming a resilient network interwoven with collagen, provide skin elasticity and allow for deformation and recoil. However, these dermal components alone do not account for the spatial orientation and positional stability of the skin over time.

This review highlights the anatomical features, mechanical properties, and age-related changes of the retinacula cutis, while distinguishing its function from that of traditional dermal extracellular matrix components. The clinical relevance of these findings is discussed in the context of facial aging, viscoelasticity, and soft tissue repositioning procedures.

Keywords: retinacula cutis, collagen dermal connective tissue, extracellular matrix components, skin aging

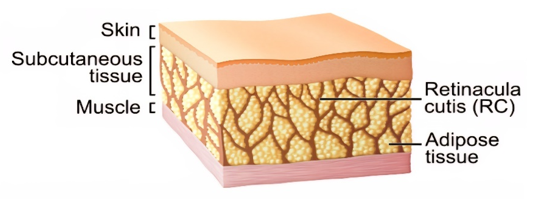

The skin and its underlying tissues comprise a complex biomechanical system composed of distinct yet interconnected layers—epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis—each contributing to the mechanical and physiological properties of the integumentary system.1,2

The dermis, rich in collagen types I and III, provides tensile strength, while elastic fibers enable recoil after deformation.1 The subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis), which contains adipocytes embedded in a collagenous matrix, plays a role in energy storage, insulation, and shock absorption, but also contributes significantly to the skin's mechanical behavior.3

Recent advances in imaging and histological analysis have highlighted the role of the retinacula cutis (RC)—fibrous septa that traverse the hypodermis—in anchoring the dermis to the deep fascia, providing vertical structural support, maintaining compartmentalization of the adipose lobules, and resisting gravitational descent.4,5 This system ensures the stability of the overlying skin and modulates its response to mechanical stress, aging, and volumetric changes.6

Anatomical and histological characterizationThe retinacula cutis consist of vertically oriented connective tissue structures that span the subcutaneous adipose layer, serving as anchoring fibers that link the dermis to the underlying deep fascia.5 The superficial fascia, composed of loosely organized collagen and elastin fibers, is penetrated by these retinacular fibers. These fibers may be denoted as superficial or deep retinacula, depending on their anatomical attachment points.4

According to Herlin et al., retinacula cutis are best described as constant, dense connective structures not dependent on fat lobule architecture (Figure 1).4

Figure 1 Three-dimensional organization of the retinacula cutis distribution and density, with increased presence in the facial and palmar regions and lower density in gluteal and abdominal areas. Reproduced from Herlin et al.4

In their anatomical study Nash et al. demonstrates that skin ligaments vary significantly in density and organization depending on anatomical region, with a greater presence noted in the face, mammary tissue, hands, and soles, and sparse distributions in the gluteal, abdominal, and perineal regions.7

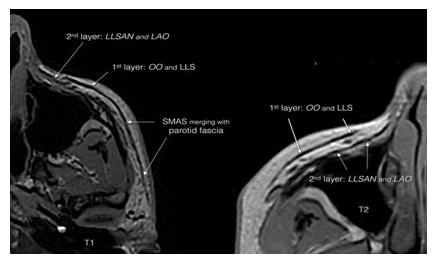

Functional significanceThe RC acts as a supportive scaffold for subcutaneous fat compartments and stabilizes skin mobility. Functionally, it counteracts gravitational descent and dynamic shear forces, maintaining the dermis in its anatomical position.5 Sakata et al. highlighted the correlation between RC density and facial skin firmness, where reduced RC density contributes to soft tissue sagging (Figure 2).5

Figure 2 Regional differences in retinacula cutis distribution and density, with increased presence in the facial and palmar regions and lower density in gluteal and abdominal areas. Reproduced from Sakata et. al.5

Furthermore, RC plays a mechanical role in tissue mobility and proprioception, mediating tension between the skin and underlying musculoskeletal structures. Variability in its thickness and tensile strength is modulated by adipose volume, vascularity, and innervation.5

Retinacula cutis and skin agingRecent studies demonstrate a clear association between RC integrity and age-related skin changes. In aging, structural remodeling of retinacula occurs, leading to decreased elasticity and increased susceptibility to wrinkles and ptosis.8

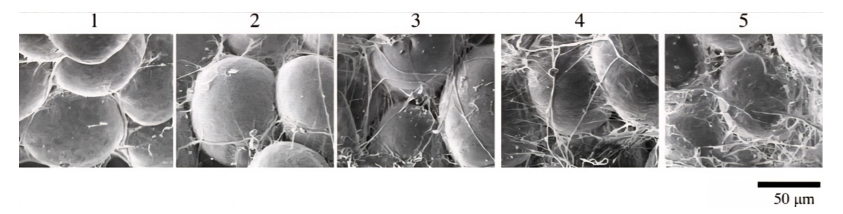

Using scanning electron microscopy, Mizukoshi et al. observed increased fiber thickness and density surrounding adipocytes in aged individuals, reflecting fibrotic changes. These modifications in the fibrous architecture were linked to reduced skin viscoelasticity on ultrasound elastography. Importantly, the RC structure traversing the subcutaneous layer decreases with age, potentially altering tissue response to mechanical stimuli (Figure 3).8

Figure 3 Age-related fibrotic changes in the periadipocyte fibrous architecture, with increased fiber thickness and density observed in aged individuals. Reproduced from Mizukoshi et al.8

Moreover, in a histological study of facial skin, Tsukahara et al, demonstrated that not only the structural integrity but also the density of the retinacula cutis is associated with skin aging. Regions with lower RC density were correlated with deeper wrinkles, suggesting a direct relationship between the organization of the fibrous septa and the visible signs of aging.9

Retinacula cutis and weight lossThe superficial fat compartment is anatomically divided into two distinct strata: the areolar adipose tissue (AAT), commonly identified as the hypodermis, and the lamellar adipose tissue (LAT). These layers are demarcated by fibrous septa known as the retinacula cutis, which provide compartmental organization and mechanical cohesion. The three-dimensional organization of these structures directly influences tissue mobility and the distribution of subcutaneous fat.10

In that way, rapid changes in adipose volume, such as those observed in accelerated weight loss, promote an early reduction in LAT volume, exposing the architecture of the AAT, which may result in contour irregularities and skin laxity.10

Fascia and retinacula cutis: A unified perspectiveContemporary fascia definitions incorporate RC within a broader fascial continuum. The Fascia Nomenclature Committee and Adstrum et al. describe fascia as a 3D network of connective tissues, including superficial and deep fascia, septa, aponeuroses, and retinacula.11,12 This view recognizes the RC as a specialized fascial component involved in mechanical signaling and force transmission.

The fascial system's biomechanical integration supports the concept that RC, beyond anchorage, contributes to tissue homeostasis and intercompartmental communication.13 Additionally, recent studies using musculoskeletal ultrasonography reinforce the applicability of imaging evaluation of fascial structures, including the bands of the retinacula cutis (Table 1).12

|

Component |

Tissue composition |

Primary Function |

Typical location |

|

Superficial fascia |

Loosely arranged collagen and elastic fibers |

Allow skin mobility over underlying layers |

Subcutaneous layer (abdomen, limbs) |

|

Retinacula cutis |

Dense vertical connective tissue septa (fibrous ligaments) |

Anchors dermis to deep fascia, maintains skin stability |

Face, palms, soles |

|

Deep fascia |

Dense, regularly arranged collagen bundle |

Encloses and supports muscles and organs |

Deep to the hypodermis and muscle layers |

Understanding RC architecture is essential in aesthetic procedures, particularly those targeting soft tissue repositioning and volume restoration. Fillers, biostimulators, and energy-based devices interact with this connective network, and variability in RC density may explain differential responses to these treatments.

Moreover, the degeneration or fibrosis of RC may underlie pathological conditions such as cellulite or lipodystrophy, where altered connective tissue structure modifies surface topography.14

Cellulite is characterized by a mechanical disequilibrium at the interface between the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue, where a disparity between inward retentive forces and outward protrusive pressures leads to topographical unevenness of the skin. When extrusion forces, such as weight gain and fluid retention, exceed the containment forces provided by the retinacula cutis, skin dimpling and irregularities appear.15

Furthermore, fibrosis and remodeling of the retinacula cutis bands lead to hardening and shortening of the connective tissue septa, increasing their downward traction on the dermis and contributing to the characteristic depressions of cellulite. This process may be driven by impaired fluid drainage, increased interstitial pressure, and chronic inflammation, reinforcing the imbalance between extrusion and containment forces.15

Retinacula cutis are crucial anatomical elements for dermal support, viscoelastic properties, and subcutaneous organization. Their age-related decline and regional variability must be considered in both clinical dermatology and aesthetic interventions. Further investigations into the modulation of RC through therapeutic strategies may open new avenues in skin rejuvenation and tissue engineering.

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2025 Cunha, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.