Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 3

Department of Dermatology, Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Correspondence: Egídio Freitas, Department of Dermatology, Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Received: July 13, 2022 | Published: July 25, 2022

Citation: Egídio F, Ana ML, Glória CV, et al. Rapidly progressive necrotic ulcers in an immunocompetent patient. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2022;6(3):57-58. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2022.06.00210

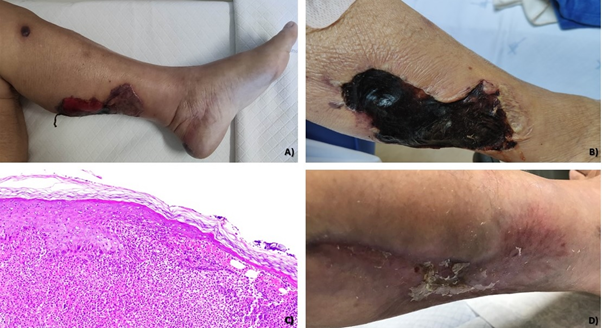

A 77-year-old woman with no family or personal history of interest was admitted for a weeklong nasal impetigo and serohematic blisters which have been appearing for four days on the 3rd left-hand finger and lower limbs (Figure 1.A). She denied trauma, insect bite, and other etiologic factors. Three days later, serohematic blisters started evolving to necrotic ulcers, with associated fever, hypotension and increment of inflammatory parameters. Examination revealed 1-15 cm necrotic ulcers surrounded by well-defined, irregular, and raised borders, with gradual growth on both legs and right foot (Figure 1.B). Skin biopsy showed skin ulceration associated with epidermal necrosis, with marked transcutaneous suppuration (Figure 1.C). Tissue microbiology demonstrated a methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Blood and urine cultures, viral and bacterial serologies, and immunological and oncological investigations were negative. Blood cell morphology was normal. What is your diagnosis?

Figure 1 A) Serohematic blisters 1-15 cm in diameter on the left leg. B) Well-defined, 1-15 cm, irregular and raised borders, necrotic ulcers on the legs. C) Cutaneous ulceration associated with epidermal necrosis, with marked transcutaneous suppuration. D) Clinical resolution after intravenous flucloxacillin for three weeks..

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG)

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a cutaneous infection most commonly associated with Pseudomonas bacteremia.1 EG can also be caused by other gram-negative bacteria (such as Aeromonas hydrophilia, Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Neisseria gonorrhea, Citrobacter freundii, Serratia, marcescens), fungus (Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Fusarium solani, Pseudallescheria boydii and Curvularia sp) and viruses (Herpes simplex 1 and 2 and Varicella zoster virus). Rarely, it may also be associated with gram-positive organisms, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.2-4 Very few cases have been described as being triggered by MSSA.5 EG usually appears in critically ill and immunocompromised patients. Although rare, EG has been described in immunocompetent patients.6

EG usually begins as red, round, painless cutaneous patches that quickly become pustular with surrounding redness with subsequent evolution to hemorrhagic blisters. Hemorrhagic blisters spread peripherally and evolve into a gangrenous ulcers with black/gray crusts, surrounded by a red halo.7 This clinical path can occur in less than 12 hours.8 EG may arise at any location, but it predominantly affects the legs, anogenital area, and armpits. The trunk, arms, and face are less often involved.9

EG results from pathogen invasion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue veins and arteries walls. This phenomenon can come from within the vessel, as a consequence of septicaemia, or by direct cutaneous inoculation. Vessel wall damage initially causes disruption of local blood supply, with redness, swelling, pustule formation, haemorrhage and skin necrosis.8

Some tests can be performed to identify the cause of infection and contribute to diagnosis confirmation. Pustule or blister fluid should be collected for gram stain and blood cultures are usually drawn. Skin biopsy should be realized for routine histology and tissue cultures.8

Classically, EG histopathology shows vascular necrosis with many surrounding bacteria but few inflammatory cells. Oedema, haemorrhage, and necrosis are seen surrounding and within involved vessels.10 Cutaneous biopsy pathology from our patient did not reveal the typical findings of EG, such as blood vessel invasion and vasculitis. However, considering clinical presentation, wide anatomic distribution of lesions, and associated systemic symptoms - which are not usually reported in deep impetigo and ecthyma, - our patient’s diagnosis is more consistent with EG.

The differential diagnosis of EG includes ecthyma, pyoderma gangrenosum, necrotizing fasciitis, extensive necrotizing paraneoplastic vasculitis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, livedoid vasculopathy, septic emboli, and diabetic microangiopathy.11

Treatment of EG usually requires antipseudomonal treatment. Antipseudomonal penicillin (piperacillin) associated with an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) should be used while waiting for microbiology results.12 Unlike other infections caused by S aureus, there are no published guidelines for staphylococcal EG treatment. Dicloxacillin, cephalexin, nafcillin, or cefazolin may be used for methicillin-sensitive strains.13

The diagnosis of MSSA EG was assumed in our patient, probably through autoinoculation of nasal impetigo. She was treated with intravenous flucloxacillin for three weeks with complete clinical resolution and anatomic and functional preservation (Figure 1.D). This case represented an enormous diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. The described diagnosis is rare, with very few reports of MSSA EG in immunocompetent patients published in literature.

None.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Egídio, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.