Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Case Report Volume 1 Issue 3

Getulio Vargas University Hospital, Amazonas Federal University, Brazil

Correspondence: Francisco Ronaldo Moura Filho, Getúlio Vargas Universitary Hospital, Teacher Samuel Benchimol Street, number 543, apt 1506, tower 2, Neighborhood Park November 10, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, Tel 85 99736-6000, Fax 88 3437-1206

Received: September 09, 2017 | Published: September 20, 2017

Citation: Filho FRM, Silva DFD, Damasceno SDA, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia during treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2017;1(3):74-76. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2017.01.00017

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a predominantly frontotemporal type of cicatricial alopecia that determines an irreversible loss of hair strands. Its cause is unknown, however reports suggest that hormonal and immunological factors are involved in its etiology. It affects postmenopausal women more frequently and there are no cases associated with chronic hepatitis C in literature. This study reportsa frontal fibrosing alopecia associated with treatment for hepatitis C with interferon and ribavirin.

Keywords: frontal fibrosing alopecia, cicatricial alopecia, hepatitis C, interferon, ribavirin

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by permanent hair loss. The disease manifests as frontotemporal hairline recession associated with eyebrows hairloss.1,2 Several papers also reportedhair loss in other areas, such as axilla, pubic, arms and legs.1,2 It was first described in 1994 by Kossard and the etiology of fibrosing frontal alopecia is still unknown.

A hormonal etiology has been defended due to the observation of the disorder in menopausal women.2,3 Recently, the coexistence of frontalfibrosing alopecia with autoimmune diseases, such as lupus erythematosus and vitiligo, has contributed to an immunological basis in its pathogenesis.4,5 There are no data of frontalfibrosing alopecia associated with hepatitis C treatment with interferon and ribavirin.

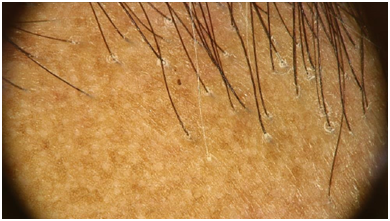

A 48-year-old female patient with priorhistory of 11 years of breast cancer, reported loss of eyebrows and hair associated with desquamation. The symptoms started during eighth month of treatment for hepatitis c with interferon and ribavirin. Her hepatitis C viral load was negative.A physical exam showed hair rarefaction in the frontotemporal hairline and eyebrows (Figure 1). The dermoscopy exam showed concentric perifollicular scaling, broken hairs, loss of follicular openings and absence of velus hair in hairline.Routine tests, including thyroid function, serum glucose, aminotransferases and laboratory test for syphilis were normal (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2 Dermatoscopy of the frontal region presented concentric perifollicular desquamation, absence of velus hair and loss of follicular openings (70x).

Figure 3 Dermatoscopy of the right temporal region presented concentric perifollicular desquamation, absence of velus hairs and white dots (20x).

Figure 4 N=57; Epidemiological distribution of the pathological fractures, traumatic fractures, and nonunion.

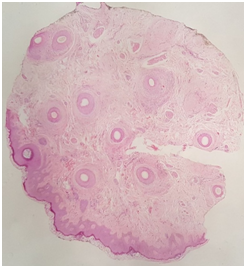

The histopathological exam showedconcentric fibrosis around the hair shafts, some of which showed apoptotic cells in its sheat, moderate perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrateand follicular drop-out (Figures 5-7). The treatment included topical clobetasol 0,05%, associated with 5% minoxidil and doxyciclin for anti-inflammatory effectwith a partial improvement.

Figure 5 Panoramic view with transversal section showing predominance of hairs in the anagen phase and follicular drop-out (20x).

Many authors consider frontal fibrosing alopecia a variant of lichen planus pilaris, as the clinical and pathological findings are difficult to distinguish.6 However, the predominantly frontal hair loss and postmenopausal age women affectedin frontal fibrosing alopecia differs from classic lichen planus.1 Lichen planus pilaris commonly is associated with lesions in other areas such as skin, mucosa and nails, unlike frontal fibrosing alopecia. Moreover, it is histologically characterized by lymphocytic lichenoid infiltrate, perifollicular fibrosis and the presence of apoptotic cells culminating in destruction and subsequent scarring alopecia.2 Consequently, the affected skin is atrophic, hyperkeratotic and with absence of follicular ostia, associated with frequent rarefaction of the eyebrows.1

There is no paper report of frontal fibrosing alopecia related with hepatitis C or its treatment with interferon and ribavirin, however, it is known that combination of interferon and ribavirin can trigger many types of hair loss as telogen effluvium, alopecia areata and universal alopecia.7 There is only a singular case of cicatricial alopecia in a patient using interferon without treatment of hepatitis C; however, in this particular case the histopathological examination revealed a diffuse cutaneous fibrosis with mixed inflammatory pattern, different from the lymphocytic infiltrate pattern, characteristic of frontalfibrosing alopecia.8

Its widely known that chronic hepatitis C infection is related to several extrahepatic autoimmune diseases, caused either by direct action of the virus in the tissues, by formation of immunocomplexes, or cross-immune reaction with the presence of autoantibodies.9 Among dermatological extrahepatic manifestations are cryoglobulinemia, porphyria cutanea tarda, palpable purpura, lichen planus, vitiligo and psoriasis.10 In addition,there are skin diseasesthat may appear or worsen during the combination treatment of interferon and ribavirin. These manifestations can range from eczematous lesions to autoimmune processes, such as sarcoidosis and psoriasis.11,12

Thewide variety of dermatological manifestationsrelated both by hepatitis c virus andits antiviral treatment makes a difficult stabilishment of a causative effect reaction. Physicians may be attempt to hair loss complain during hepatitis c treatment and be aware that different types of alopecia, besides telogen effluvium, including scarring alopecia may affect these patients.

Therefore, a dermatological evaluation of the patients being treated for hepatitis C is paramount so that diagnosis and previous treatment avoid permanent sequelae.

We would acknowledge Francisco Gustavo Silveira Correiafor editing and adding information tothis study.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this case report.

Informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patient.

©2017 Filho, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.