Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 4

1School of Medicine, Creighton University, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

2CHI Health Creighton University Medical Center – Bergan Mercy, Omaha, NE 68124, USA

3Department of Surgery, Ridgeview Medical Center, Waconia, MN 55387, USA

4Department of Surgery, Lakeview Clinic, Waconia, MN 55387, USA

Correspondence: Mitchell Taylor, School of Medicine, Creighton University, Omaha, NE 68178, Mailing Address: 3920 Dewey Ave, Omaha, NE 68105, USA, Tel 612-356-0360

Received: November 17, 2022 | Published: December 5, 2022

Citation: Taylor M, Blomberg W, Taylor K. Dedifferentiated primary melanoma with rhabdoid features: a case report and literature review. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2022;6(4):108-110. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2022.06.00221

Rhabdoid melanoma is an aggressive, rare variant of melanoma. Herein, we describe a case of rhabdoid melanoma and review the clinicopathological features of this neoplasm. A 59-year-old Caucasian female presented with a large cavitary wound located on her right posteromedial upper torso. Light microscopy of the lesion revealed patternless sheeting of neoplastic cells with cytoplasm containing eosinophilic inclusions and peripherally located large round-to-oval nuclei. Tumor cells stained positive for S100, Sox10, myoD1, desmin, and vimentin. CT imaging of the abdomen, chest, and pelvis demonstrated bilateral cannonball lung tumors, bilateral axillary and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and a soft tissue mass involving the left upper back. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of metastatic rhabdoid melanoma, which ultimately resulted in the patient’s demise. Increased awareness of this rare entity is crucial to the practicing physician in order to enhance recognition and provide the best possible healthcare to affected individuals.

Keywords: rhabdoid tumor, melanoma, rhabdoid melanoma, melanoma with rhabdomyoblastic features, rhabdomyoblastic histology

Malignant melanoma is a tumor arising from the malignant transformation of melanocytes, which are cells derived from the neural crest and responsible for pigment production in the basal layer of the epidermis.1 In recent years, the incidence of melanoma has stabilized after decades of increase.2 However, mortality and morbidity remain significant, where an estimated 99,780 new cases and 7,650 deaths of melanoma are anticipated in 2022. While melanoma remains one of the most survivable malignancies with 93% survival for all combined stages, a substantial portion of the mortality is considered preventable with early surgical and medical interventions. Due to its superficial nature, early recognition and treatment is more reasonably attainable than with elusive internal metastases. Light skin tone and ultraviolet radiation are the most robust risk factors for developing melanoma. Further investigation of risk factors and treatment modalities, especially with histologically diverse forms of melanoma, are needed.

Melanoma is known for its metaplasticity and may present with a variety of cytomorphological features, stromal changes, and architectural patterns.3 Melanoma can mimic a large variety of neoplasms and demonstrate epithelioid, clear cell, spindle, signet ring, or rhabdoid morphology.4 Rhabdoid melanoma was initially described by Bittesinii et al. in 1992 and is histologically characterized by abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, round nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and large hyaline cytoplasmic inclusions.5,6 This form of melanoma is incredibly rare and appears mainly as a metastatic or recurrent form.7 Currently, only 14 cases of primary rhabdoid melanoma have been reported in the literature.5,7-15 Risk factors are thought be similar to those of malignant melanoma, however the limited number of cases limits further investigation. Recognition and diagnosis of this rare form of melanoma is crucial in avoiding misdiagnosis and determining appropriate treatment strategies.5

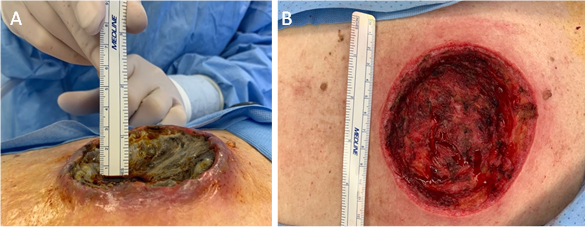

We report here the case of a 59-year-old Caucasian female who presented to the clinic with fevers, chills, and a large, non-healing, cavitary 9.5 l x 7.0 w x 3.0 d cm wound located on her right posteromedial upper torso. (Figure 1) Upon presentation, the patient described what started as a small “skin tag” under her right bra strap two months prior which had enlarged significantly over the previous month. The lesion was associated with pain, bleeding, purulent discharge, and a pungent foul odor. Further examination of the wound revealed raised, erythematous edges and gray necrotic material at the base. The patient was referred to surgery for wound debridement and biopsy of the wound base, which displayed a high-grade malignant neoplasm.

Figure 1 A) A solitary, well-defined 9.5 l x 7.0 w x 3.0 d cm lesion of the right posteromedial upper torso with raised, erythematous edges and central grey necrotic material. B) Base of the lesion following surgical debridement and clearing of central necrosis.

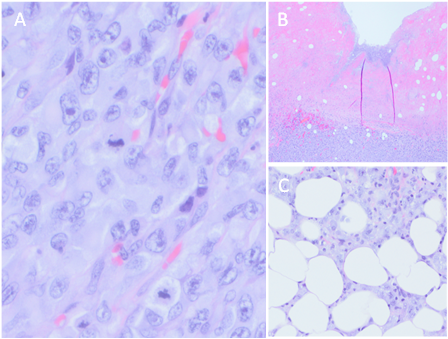

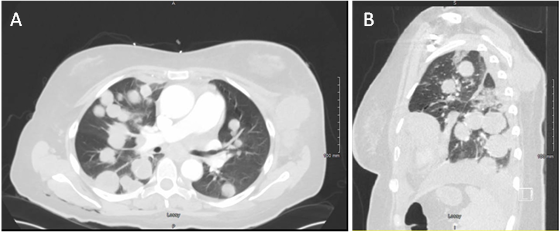

Light microscopy of biopsied tissue showed patternless sheeting of neoplastic cells with cytoplasm containing eosinophilic inclusions and peripherally located large round-to-oval nuclei. (Figure 2) Immunohistochemically, neoplastic cells were focally positive for S100, Sox10, myoD1, and desmin as well as diffusely positive for vimentin. Lesional cells were negative for HMB-45, Melan-A, CD31, CD34, ERG, smooth muscle actin, myogenin, caldesmon, keratin 7, keratin 20, Oscar keratin, and keratin AE1 AE3. Non-contrast computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed numerous bilateral cannonball lung tumors, extensive bilateral axillary and mediastinal adenopathy, and a soft tissue mass involving the left upper back superior to the site of the surgical debridement. (Figure 3) These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of dedifferentiated primary melanoma with rhabdoid and heterologous rhabdomyoblastic features.

Figure 2 A) Neoplastic tissue exhibiting patternless sheets of frequently multinucleated tumor cells demonstrating rhabdoid eosinophilic cytoplasm displacing an eccentric nucleus and large nucleoli. B) Ulcerated surface of the neoplasm with bacterial growth in the necrotic debris. C) Invasion of the tumor deep into the subcutaneous tissue.

Figure 3 A) CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed numerous bilateral cannonball lung tumors, extensive bilateral axillary and mediastinal adenopathy, and B) a soft-tissue mass involving the left upper back superior to the site of surgical debridement.

Possible treatment plans of combined ipilimumab and nivolumab immunotherapy, radiation therapy, or palliative care were discussed. It was determined that the patient was not a candidate for immunotherapy, as the 6–8-week latency period extended beyond the patient’s life expectancy of days to weeks. The patient elected to pursue radiation therapy and completed 3 of her 14 scheduled doses of radiation before being readmitted to the hospital for acute on chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure. After further discussion, the decision was made to transition the patient to hospice care, as continued radiation would likely not make a difference in her overall symptom burden or survival benefit. The patient died the following day.

Malignant rhabdoid tumor is a rare and high-grade neoplasm diagnosed primarily in young children and less commonly in adults.16 The term rhabdoid was first used in 1981 by Haas et al. in reference to several pediatric neoplasms thought to be a rhabdomyosarcomatous variant of Wilms tumor.17 However, subsequent studies failed to demonstrate rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, which led to the rhabdoid tumor later being identified as a distinct entity.18 These tumors exhibit an aggressive tumor biology and are associated with a high likelihood of fatality in patients.8

Since first being described, a variety of extrarenal malignant rhabdoid tumors showing similar morphologies have been reported in soft tissue and various organs including the brain, uterus, lung, ovary, prostate, liver, and skin.19 Rhabdoid melanoma belongs to this diverse group of extrarenal rhabdoid tumors and morphologically mimics rhabdomyoblasts without evidence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation.20 This unique variant of melanoma was initially described in 1992 when Bittesini et al. reported the case of a 74-year-old man presenting with an enlarging left axillary mass. The mass was found to be composed of enlarged, neoplastic lymph nodes, and a biopsied specimen was compatible with a diagnosis of metastatic rhabdoid melanoma. However, no primary lesion was identified at the time.

Rhabdoid melanoma has since been recognized as a distinct subtype of malignant melanoma.6 It appears to have no age or sex predilection, with men and women from all age groups being equally affected.20 The most commonly affected sites of primary rhabdoid melanoma include the shoulder, scalp, thigh, and back. Metastatic rhabdoid melanoma has been observed to involve lymph nodes, soft tissue, small intestine, liver, lung, and skin. Very few cases of primary rhabdoid melanoma have been identified and discussed, as metastatic lesions are found to be much more common.9 To date, only 14 cases of primary rhabdoid melanoma have been described in the literature.5,7-15

Histologically, rhabdoid melanoma is highly cellular and characterized by medium-to-large sized cells with a round, ovoid, or polygonal shape.16 The rhabdoid cells contain a vesicular nucleus demonstrating one to several prominent nucleoli and a characteristic paranuclear inclusion body, which displaces the nucleus into an eccentric position. The presence of rhabdoid cells is variable across tumors, where some are composed exclusively of rhabdoid cells and others have few to none.9 In a case series done by Chang et al., the histological and immunohistochemical profiles of 31 different samples of rhabdoid melanoma metastases from 29 different patients (17 men and 12 women) were described.21 Their study found that 48% (15 out of 31) of the neoplasms were composed almost exclusively of rhabdoid cells, while the remaining 52% (16 out of 31) consisted of less than 25% of rhabdoid cells.

Immunohistochemical characteristics of rhabdoid melanoma demonstrate a high degree of heterogeneity.15 However, all reported cases of rhabdoid melanoma tend to express at least one melanocytic marker, including either S100, HMB-45, or Sox10. Historically, the most consistently reported positive stain has been S100, found to be positive in 13/14 reported cases of primary melanoma with rhabdoid features. Reported here, we observed positive staining for both Sox10 and S100 melanocytic markers, with negative staining for HMB-45. Similarly, Borek et al. described a series of three rhabdoid melanoma cases where lesional cells stained positive for S100 and negative for HMB-45.8 The loss of HMB-45 staining has been noted in the literature by several authors, who, in addition to HMB-45, have observed cases that failed to stain for S100. While the reasoning behind this observation remains uncertain, some speculate that the rhabdoid phenotype represents dedifferentiation to a more primitive neoplasm that no longer expresses these characteristic melanocytic markers.

Rhabdoid melanomas are also conventionally shown to stain positive for the mesenchymal markers vimentin or desmin, as was seen with our patient.13 Vimentin is a type III intermediate filament suggestive of cells with mesenchymal origin or those undergoing endothelial to mesenchymal transition.15 Desmin is a smooth muscle type fiber found in muscular differentiation. To date, 13/14 reported cases have stained positive for vimentin and 3/14 cases have stained positive for desmin. The case reported here displayed positivity for both desmin and vimentin, exhibiting immunohistological evidence of mesenchymal and melanocytic origin that is found in rhabdoid melanoma.

©2022 Taylor, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.