Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Case Report Volume 3 Issue 5

1Tropical and Infectious Diseases Division, Internal Medicine Department, Indonesia

2Faculty of Medicine Universitas Airlangga, Dr. Soetomo General Academic Hospital, Indonesia

Correspondence: Erwin Astha Triyono, Tropical and Infectious Diseases Division, Internal Medicine Department, Indonesia, Tel 08123259941

Received: September 25, 2019 | Published: October 18, 2019

Citation: Triyono EA, Fonda T. A case report an HIV patient with acute perikarditis. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2019;3(5):132-136. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2019.03.00130

Infection of Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Acquired immune deficeincy syndrome (AIDS) is a global issue. There were around 36.7 million people in the world who were infected with HIV in 2016 and 1 million people die each year.1 HIV infection is often associated with heart problems . However, cardiac involvement in this patient population is often underdiagnosed or associated with other disease processes.2

The prevalence of cardiovascular disorders in HIV/AIDS patientsreached 30-60% and up to 24% in one autopsy series .3,4 Pericardial lesions are a frequent cardiovascular diseases, the prevalence of pericardial lesions in HIV/AIDS patients nearly 28% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and 35.3% in Congo Brazzaville. HIV/AIDS patients with pericardial effusion accounted for 20% and 4% of them with massive effusion.3

Heart disease in patients with HIV/AIDS has many challenges both in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic. The high prevalence of cardiovascular disorders, especially pericardial lesions in HIV / AIDS patients, further confirms the magnitude of the problem. Pericarditis itself is a serious disease and is almost always fatal because of late management. The pathogenesis of this event is also unclear.5

Considering the magnitude of the problems that occur in patients with HIV / AIDS with cardiovascular disorders , the authors would like to discuss this issue further,especially in relation to acute pericarditis. The authors present a case regarding a HIV/AIDS patient with acute pericarditis.

tattoos, acute pericarditis, sweating, oral ulcers

Mr. M.S., age 44 y.o., a fruit seller living in Surabaya came to the emergency department of Dr. Soetomo Hospital. He was referred from Karang Tembok Hospital with inferior STEMI and a history of pulmonary TB. The patient complained of stabbing chest pain since 3 days before admission . Pain was felt continuously in the middle of the chest, worsened by breathing in and he felt better when in sitting and bending position . He denied hot or burning sensation, sharp pain in hypocondrium, and nausea and vomiting. He also complained shortness of breath, especially on activity. Cough was denied. He complained fever since >1 month before admission, and worsened 1 week before admission. He also complained decrease of body weight since last month for around 6kg (from 57kg to 51kg), and also decrease of appetite. Night sweating, oral ulcers, pain on swallowing and diarrhea were denied. Complaints of reddish skin, hair loss, joint pain weredenied. There were no complaints of tumors/lumps.

The patient didin’t have history of diabetes, high blood pressure, jaundice, heart disease or kidney disease. The patient had a history of tuberculosis in 1999, received treatment for 6 months and was declared cured. His father-in-law, who had been living in the same house with the patient,had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis, but had received treatment and was declared cured. There weren’t other family members suffering from lung diseas. The patient had been married since 20 years ago and had two boys, now aged 10 and 18 years. His wife and his two children denied any complaints. History of drugs, tranfusion, tattoos were denied. He had multiple sexual partners before mariage, and he admitted using prostitutes’ services several times during his marriage.

On physical examination, he was alert, with Glasgow Coma Scale ( GCS ) E4V5M6. Blood pressure (BP) was 112/67mmHg, pulse 120 beats per minute, regular, respiratory rate (RR) 22 times per minute and axillary temperature 37.60C, oxygen saturation was 98% with O2 nasal canule 3 lpm . Head and neck examination showed no conjungtival pallor, jaundice, dyspneu, nor cyanosis. There were no increase in jugular venous pressure ( JVP ) nor lymph nodes enlargement. On chest examination, there was a pericardial fiction rub in the left parasternal border, heart sounds within normal limit without murmurs, gallops or extra systole; no abnormality was found on pulmonary examination. Abdominal examination did not reveal any abnormalities . Extremities perfusion were warm and dry, no edema, capillary refill time < 2 seconds.

From the laboratory examination, leukocytes 8690/μL, Hemoglobine11.2g/dL, neutrophils 78.3%, lymphocytes 19.4%, hematrocrit 37.3%, platelet 489000/μL, Blood sugar 75mg/dL, 17mg/dL, creatinin serum 1.14mg/dL,AST 38 U/L , ALT 39U/L , albumin 3.28 gr/dl, sodium 129mmol/L, potassium 3.8mmol/L, chloride 105mmol/L , HBs Ag non reactive, HIV rapid test reactive, APTT 24.1 seconds, PPT 9.5seconds, Troponin I 6.18pg/ml (Normal<14pg/ml), CKMB 11.2U/L (Normal 7-25U/L), CRP 197.16 mg/L. BGA examination results pH 7.41, pCO2 25mmHg, pO2131mmHg, HCO3 15.8mmol/l, Beecf-8.8mmol/l, SO2 99% with O2 nasal cannula 3 lpm. An ECG showed as in us tachycardia 124 beats per minute with wide spread concave ST elevation and PR depression throughout most of the limb leads (I, II, III, a VL, a VF) and precordial leads (V2-6), reciprocal ST depression and PR elevation in lead a VR and V1. Chest X-Ray showed the presence of suprahilar fibrosis on the right lung. Echocardiography result was within normal limit:

Patient was diagnosedwith HIV stage III with acute pericarditis and suspected relapse of pulmonary TB. As treatment, patient recieved high calories and high proteins diet 2100kcal per day, O2 nasal cannula 3 lpm, ceftriaxone 1g every 12 hours (iv), ranitidine 50mg every 12 hours (iv), colchicine 0,5mg orally every 24 hours and ibuprofen 600mg orally every 8 hours.An HIV antibody testing, sputum smear with Gram and Ziehl-Nielssen (ZN) staining, blood and sputum culture, and GeneXpert MTB/RIF on sputum were ordered.Serial ECG monitoring was ordered. CD4 count was not ordered because of financial issue.

On the second day of care,the patient’s chest painimproved. He was alert, with blood pressure 110/70mmHg, pulse 110 beats per minute, RR 20 times per minute, temperature 36.6°C, O2 saturation 99% with O2 nasal cannula 3 lpm. The results of HIV antibody tests were positive.

On the sixth day of care, the patient had no complaints. He was alert, with blood pressure 120/70 mmHg, pulse 100 beats per minute, RR 16 times per minute, and temperature 36.5oC , O2 saturation 99% without O2 support.Laboratory examinations: leukocytes 9410/μL, Hb 11.9g/dL, neutrophils 87,5%, hematocrit 35.6 %, platelets 304000/μL. GeneXpertresult was negative for MTB. Sputum staining for Gram and ZN were negative. Blood culture and sputum culture were negative. ECG examination showed sinus rhythm 98 times per minute. The patient was diagnosed with HIV stage III with improved acute pericarditis and a history of pulmonary TB. The patientwas discharged with the following medications: ibuprofen 600mg-600mg-400mg po, cotrimoxazole 960mg/day po, colchicine 0.5mg/day po, and fixed dose combination (FDC) of antiretroviral therapy (Tenofovir/TDF 300mg, Lamivudine/3TC 150mg efavirenz/EFV 600mg) 1tab/day po.

Three days after being discharged, the patient had no complaints. He was told to continue his medications, withibuprofen tapered downfor 200mg every week. The patient chose to continue his treatment at Karang Tembok Hospital.

AIDS is a syndrome caused by decrease of immunity caused by infection of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) belonging to the family of retroviridae, in which AIDS is the final stage of HIV infection.6 Classification of HIV/AIDS stage by WHO can be seen in table 1-4.

Primary HIV infection |

|

Asymptomatic |

|

Clinical Stadium I |

|

Asymptomatic |

|

Clinical Stadium II |

|

Symptomatic |

Angular cheilitis |

Clinical Stadium III |

|

Severe weight loss (>10%) |

Severe presumed bacterial infections |

Clinical Stage IV |

|

HIV wasting syndrome |

Extra pulmonary cryptococcosis |

Table 1 WHO HIV/AIDS clinical stadium in young adults and adults.16

Drugs |

Usual dosing |

Duration of therapy |

Tapering |

Aspirin |

750-1000mg every 8 hours |

1-2 weeks |

Decreased doses by 250-500mg every 1-2weeks |

Ibuprofen |

600mg every 8 hours |

1-2 weeks |

Decreased doses by 200-400mg every 1-2weeks |

Colchicine |

0.5mg once daily (<70kg) or 0.5mg every 12 hours (≥70kg) |

3 months |

Not mandatory, alternatively 0.5mg every 48 hours (<70 kg) or 0.5mg every 24 hours (≥70kg) in the last weeks |

Table 2 Treatment of acute pericarditis.8

Therapy |

Initial dosing |

Duration |

Azathioprine |

Started at 1mg/kg/day, then gradually increased to 2-3mg/kg/day |

At least 6 months |

Human immunoglobulin |

400-500mg/kg/day (iv) for 5 days |

5 days |

Anakinra |

1-2mg/kg / day up to 100mg/day |

At least 6 months |

Pericardiectomy |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Table 3 Options for recurrent pericarditis.11

Infection |

|

Bacterial |

Gram positive and Gram negative species (streptococci, staphylococcus, pneumococcus), Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Less common - Legionella, Norcardia, Actinobacillus, Rickettsia, Borrelia burgdoferi (Lyme disease), Listeria, Laptospira, Chlamydophila psittaci, Treponema pallidum (syphilis), Coxiella burnettii, Meningococcusspecies, Hemophilusspecies, Mycoplasma |

Fungal infection |

Histoplasma, blastomyces, coccidiosis, aspergillus, candida |

Parasitic infection |

Toxoplasma, entomoeba, echinococcus |

Viral / idiopathic causes |

Coxsackie viruses, echoviruses, adenoviruses, influenza A & B viruses, enteroviruses, mumps viruses, Epstein-Barr viruses, HIV, herpes simplex viruses, type I varicella zoster virus (VZV), measles, influenza viruses type II, RSV, CMV, hepatitis A, B & C, parvovirus B 19 |

Non-Infection |

|

Autoimmune |

Systemic lupus erythematous, Sjogren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, vasculitides-eosinophilic granulomatosis (Churg-Strauss syndrome), Takayasu disease, Behcet syndrome, scarcoidosis, familial Mediterranean fever, inflammatory bowel disease, Still disease, mixed connective tissue disorder, Reiter Wegners granulomatosis, ankylosing spondylitis, giant cell arteritis, dermatomyocitis, serum sickness |

Neoplastic causes |

Primary (mesothelioma), secondary (lung, breast, etc.) |

Metabolic causes |

Uremia, myxoedema, cholesterol pericarditis |

Drugs |

Daunorubicin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5 flurouracil, amiodarone, cyclosporine, mesalazine, clozapine, methysergide, anti-tumor necrosis factor, hydralazine, procainamide, methyldopa, phenytoin, Isoniazine, clozapine, methysergide, anti-tumor necrosis factor, hydralazine, procainamide, methyldopa, phenytoin, Isoniazide, clozapine, methysergide, anti-tumor necrosis factor, hydralazine, procainamide, methyldopa, phenytoin, Isoniazide, |

Trauma, iatrogenic |

Coronary interventions, permanent pacemaker / ICD implantation , radiofrequency ablation , translucent / impermeable trauma, esophageal perforation / rupture |

Table 4 Causes of Pericarditis.16

This patient was diagnosed with HIV infection by antibody testing, and he also complained severe unexplained weight loss > 10%, unexplained persistent fever > 1 month, sohe was diagnosed with HIV stage 3

Pericarditis is categorized according to the duration of symptoms: acute,incessant, recurrent, and chronic pericarditis. Acutepericarditis is an inflammatory pericardial syndrome with orwithout pericardial effusion. Incessant pericarditis is a pericarditis which lasts for more than 4–6 weeks but less than 3 months without remission.. Recurrent pericarditis is diagnosed with a documented first episode of acute pericarditis, a symptom-free interval of 4–6 weeks or longer and evidence of subsequent recurrence of pericarditis. Pericarditis is considered chronic if it is persistent for more than 3 months. Pericarditis is often the initial manifestation of a systemic disease.7,8

Pericarditis can be caused by either an infectious etiology through pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and non-infectious etiology through the damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). This stimulus will be recognized by receptors of innate immunityboth intracellular (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, NLRs) and extracellular (toll like receptors, TLRs; and P2X2/P2X7. NLRs will be integrated into the inflammatorystructure into nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like pyrin domain-containing 3 receptors (NLRP3) which will trigger the release of interleukin 1 (IL-1). IL-1, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, will cause inflammation of the pericardium.9

The differential diagnosis of acute pericarditis includes acute gastritis, angina, acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and oesophageal disorders (esophagitis, esophageal rupture, esophageal spasms, GERD). According to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases, the diagnosis of acute pericarditis can be established if two of 4 criteria are found: pericarditic chest pain, pericardial frition rub , new widespread ST elevation or PR depression on ECG examination, and pericardial effusion (new or worsening). Pericarditic chest pain is a sharp and pleuritic painwhich improves with sitting and bending positions. Other tests that support the diagnosis are an increase in inflammatory markers such as CRP, LED or leukocytosis and evidence of pericardial inflammation from radiological examinations such as cardiac magnetic resonance and cardiac CT scans.8,10

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of pericarditis.9

This patient presented with a chest pain typical of pericarditis for 3 days, pericardial friction rub,widespread ST elevation on ECG examination, and increase in CRP (197.16mg/L). Thus, he was diagnosed with acute pericarditis .

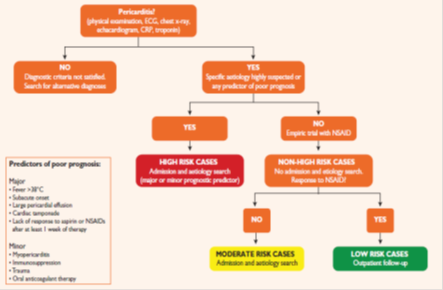

Acute pericaditis are managed according to the severity;patients are said to be high risk if they meet one of the major or minor criteria. Major criteria include fever>380C, subacute onset, massive pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, lack of response to aspirin or NSAIDsafter at least 1 week of therapy. Minor criteria include myopericarditis, immunosuppression, trauma, and anticoagulant therapy. Patients who are classified as high risk conditions require hospitalization and thorough search for etiology. Patients who are not included in the high risk group can be treated as outpatient by giving NSAIDs for 1 week. Patients who respond poorly to NSAID are considered moderate risk group and require hospitalization and etiology search, similar with the high risk group. The flow of triage for the pericarditis can be seen in Figure 2-4 .8

Figure 2 Pericarditis triage.8

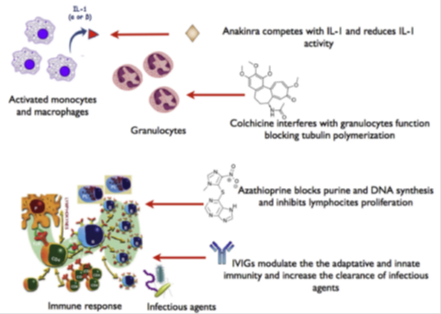

Figure 3 Emerging options for the therapy for recurrent pericarditis with their mechanism of action.11

Figure 4 Complications of acute pericarditis.9

The treatment for acute pericarditis is the administration of NSAIDs or aspirin. Several other literatures recommend the administration of NSAIDs and colchicine. Corticosteroids can be considered a second choice if there are contraindications or failure with aspirin or NSAID treatment. Therapy is given for 1-2 weeks followed bydose tapering after clinical, laboratory, and ECG improvement.8,11

The NSAID of choice for acute viral or idiopathic pericarditis is ibuprofen with an efficacy of 70-80% (Task et al., 2015).8 In patients with acute pericarditis with a history of acute myocardial infarction, aspirin is the first choice, and NSAIDs must be avoided because they interfere with the healing process. Aspirin is also preferred in patients who need anti-platelet therapy. Colchicine is preferred in recurrent pericarditis or lack of improvement with NSAIDs. Proton pump inhibitors can be given to patients with a history of gastric ulcer who require high dose NSAIDs or long-term NSAIDs use. Corticosteroids are used as a second-line therapy with low-moderate doses (prednisone 0.2-0.5mg/kgBB/day) tapered down slowly (2.5mg/2weeks) after remission and CRP improvement.11-14

Several therapeutic options for recurrent pericarditis areazathioprine, immunoglobulins, and anakinra (anti-interleukin-1). These therapiesare still controversial and have not been widely applied.11

NSAIDs work by inhibitingcyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzyme, thereby preventing the formation of prostaglandins. Ibuprofen possess both anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and capturing free radicals, and analgetic properties by binding to cannabinoid receptors. Aspirin works by exerting its anti-inflammatory properties, inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2 and regulating neutrophils.Colchicine works on white blood cells, especially granulocytes, by inhibiting tubulin and microtubule polymers that interfere with the function of inflammation and migration. Colchicine also works directly on inhibiting the formation of inflammation by inhibiting the activation of P2X2/P2X7. 9,11,15

This patientwas immunosuppressive related to HIV infection, thus he required hospitalization and further examination of the etiology of pericarditis. He was given 600mg ibuprofen therapy every 8 hours orally and colchicine 0,5mg daily orally for acute pericarditis. The etiologies of pericarditis can be divided into infectious and non-infectious cause. Infections that can cause pericarditis include bacterial, fungal, parasitic or viral infections. Non-infectious causes include autoimmune, malignancy, metabolic, drug and trauma. Viral infections are also termed idiopathic due to the difficulty in determining the exact pathogen.10

There was no sign of infection other than HIV in this patient, no sign of autoimmune disease, trauma, use of causative drugs, malignancy, nor metabolic causes. He responded well to treatment with ibuprofen and colchicine, so the most likely cause of his acute pericarditis is of viral origin. Most patients with acute pericarditis, especially those with idiopathic or viral causes, have a good prognosis. Cardiac tamponade occurs mainly in patients with specific causes such as malignancy, tuberculosis or bacterial infection. Constrictive pericarditis occurs in about 1% of patients with acute viral / idiopathic pericarditis. The risk for constrictive pericarditis is divided into low risk (1%) for viral / idiopathic pericarditis, intermediate (2-5%) for autoimmune and malignant causes, and high risk (20-30%) for those caused by bacteria, especially M. tuberculosis.8,9,16

Acute pericarditis must be considered in an HIV/AIDS patients presenting with typical chest pain. Hospitalization for immunocompromised patients such as HIV/AIDS is mandatory, due to its poor prognosis and to thoroughly search for etiology. This patient was given ibuprofen 600mg every 8 hours and colchicine 0,5mg daily for 1 week and showed a good response. The cause of acute pericaditis in this patient was most likely idiopathic/viral origin.Following satisfactory improvement, he continued treatment on outpatient basis with tapered dose of ibuprofen, colchicine, and antiretroviral therapy.

None.

None.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

©2019 Triyono, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.