Journal of

eISSN: 2378-3184

Brief Report Volume 11 Issue 3

Director of Fisheries Development of the Venezuelan Ministry of Agriculture and Breeding (MAC), Venezuela

Correspondence: Germán Robaina G, Director of Fisheries Development of the Venezuelan Ministry of Agriculture and Breeding (MAC), Venezuela

Received: September 15, 2022 | Published: October 27, 2022

Citation: Robaina GG. Some reflections about the Venezuelan pisciculture sector. J Aquac Mar Biol. 2022;11(3):100-103. DOI: 10.15406/jamb.2022.11.00343

The need to look for alternatives for feeding the enormous world population has generated that the human being seeks sources of protein at low cost and technologies of high productive capacity.

Population growth in the world is exponential and has required greater extraction of marine resources and the application of innovative productive technologies to guarantee the generation of food as a strategy to guarantee the survival of the human being.

Much of human and animal food depends to a large extent on the extraction of fishery products, resources that are not infinite and are strongly affected by environmental pollution, overexploitation, underuse, depletion and / or slow recovery of the populations that many species present, and the increasingly high costs of extraction, putting at risk the food security of the planet, and although science and technology contribute to the development of increasingly intensive animal farms, to date we have been unable to meet the food demand raised by the population increase. Venezuela is no stranger to this reality.

While SOFIA 2022 talks about the advance of aquaculture production on a global scale, Venezuela suffers from a dwindling fish production because of numerous factors.

For a population close to 30 million inhabitants, and a country that has the second highest rate of food deficiency on the continent, less than 300 tons of fishing biomass are produced through fish farming practices (< 0.01 kg/inhabitant/year and 0.3 kg/year/km2).

The problem of the Venezuelan fish reality lies not only in the fact that the governing body of aquaculture and fishing activity has prevailed a great lethargy and passivity in the promotion and support of the activity and has not adequately fulfilled its founding objectives, but also that the ministry with competence in environmental matters has been hindering however development proposal is presented, the high price of inputs and the apathy, neglect and indifference that prevails in most of the country's fish producers.

For many years the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture has been led by people of very distant academic training in fisheries and aquaculture, suffering from basic knowledge about the management and administration of the sector, and about the rules and natural laws that govern the activity, prevailing most of the time the domain of ideological guidelines alien to the own objectives for which this ministry was created and to political objectives today more exacerbated than never, without knowing many times or where the fish produced in the country comes from.

Most high-ranking officials have performed under a system of "aquaponic administration", in which nutrients are provided by a network of public officials and sycophants, in which political affinity and personal ambitions prevail more than interest in developing the sector. The few times in which a professional related to aquaculture activity has been appointed in a high rank (vice ministry), corresponds to the period in which the largest sum of aquaculture failures in the history of the country have been committed.

In a few exceptions, because if there are, officials outside the aquaculture activity have been appointed to occupy senior management positions in the area, and in some of us we have found signs of having the best goodwill to promote the development of the sector, but the constant confrontations and differences of criteria with the managerial positions and medium-level officials of the governing body of the fishing activity and its regulatory body they have impeded sound decision-making, so apparently they have found it easier to remain silent to safeguard the office, than to make the decisions that are required.

On the other hand, for some time now, the ministry with competence in fisheries and aquaculture seems to be strongly infiltrated by technicians in which the guidelines issued by the environmental sector seem to prevail over the criteria of aquaculture productivity, making it practically impossible to overcome the numerous obstacles that are imposed for the approval of a fish investment project of commercial scope. The obstacles imposed by the ministry with Competition in environmental matters - already difficult to fulfil - seems to deprive many of the current average officials of the fisheries sector.

The excess of discretion at the national level in the aquaculture sector is, to say the least, impressive. Today, after 30 years of the approval of its, there is still discussion about tilapia breeding. Each management, each position and each instance impose its own criteria. Some forward and some backward, thereby stimulating doubt, uncertainty, discretion, illegality, dis continuity, and hunger.

Today, after more than 50 years, there is talk of re-evaluating the fish potential of reservoirs, of inventorying species, of evaluating areas, of delimiting areas and of whatever obstacle one can imagine delaying the implementation of a program of mass production of fish through sustainable fish farming practices of more than demonstrated potentiality. Any fisheries inspector can and does what he sees fit, with the most extreme discretion over the few existing laws, and often without knowing that there are decrees and legal resolutions on this or that situation.

Thus, for each of the regions of the country, if an inspector does not like tilapia, there will be no tilapia. If an inspector doesn't like mariculture, mariculture there won't be, and if an inspector doesn't like floating cages, there won't be floating cages.

For some time now, the main rejections of the fish investment proposals presented allege more criteria of an extreme environmental conservation nature than food production criteria. Criteria that do not correspond or are related to the importance and benefits that aquaculture production represents for the country, respecting and promoting an activity that is much friendlier to the environment than mining exploitation and the violation of environmental preservation standards for the main Coastal Marine National Parks of the country, among others.

As it is logical to expect, there is also a large group of characters in the sector who are only looking for perks and particular solutions (the majority) to the collective ones. Those who do not respect the time of others, who do not mind hindering, abusing or deceiving. Those who take advantage of their good contacts to discredit, annul or boycott any development proposal that is not led by themselves, and those resentful who are not willing to approve an investment project, to "not allow another to enrich themselves" (sic) and those who, as in the United Nations, have the right to veto and boycott any initiative that does not come from their own imagination and / or robs them of the prominence they require to maintain their position.

We are convinced that to promote national fish development, the functioning of the official sector must be linked more closely with the private sector interested in its development. We must be more interested in the collective good than in the particular. More for the sector and the country than for personal interests.

Looking for the solution in the cachama (Colossoma), tilapia (Oreochromis), panga (Pangasius), ornamentals or our personal aquaculture problems we do not believe is the alternative, and even less through absurd proposals that only lend themselves to manipulations and arbitrariness of political dye.

That will not bring anything good or definitive for the sector. Only warm clothes for some lucky pre-selected and gifts for the organizers and protectors of the circus.

So, by action or omission, many of the main obstacles that overwhelm the national fish sector come from members of our own community who are responsible for promoting political interests, while the ordinary fish farmer, the true independent producer fails to develop his dream.

If the current scheme of indifference and mediocrity continues, the country will not achieve any substantial development, and only the few who manage to ingratiate themselves will obtain credits, permits, and share in the benefits of exports.

Putting interests against the interests of the sector, and/or using a position to promote itself and establish itself as the great promoter of the activity by overwhelmingly imposing its criteria, is not the best solution.

We do not intend with these reflections to discredit any colleague or official who is trying to do something from the governmental entities or from his trench, surely there are, it is about arousing interest and bringing together forces in a single direction and in favor of a common good.

We are not talking about ending fish farming policies of social scope that the government is advancing, much less with the caravans of the sardine, but we are convinced that these will never fill the table of all The Venezuelans, much less will sustain exports that generate foreign exchange that the country requires so much.

For all these reasons, we cannot fail to speak and criticize healthily the inadequate aquaculture policy, obsolete laws and regulations, the functioning of the sector, demand probes and trained leaders to direct their reins, promote the stimulus to production, wealth and development.

We are convinced that this is the main obstacle that has allowed Venezuelan fish farming to find itself, after 80 years of its conception, in a stage of prolonged incubation.

After waiting for more than 80 years for a natural birth, as a first-time and frightened parent, we do something, we allow it to be done, or we stop doing so that the creature cannot leave the incubator.

Thus, we have a newborn who cannot fend for himself, and finds his life and prosperity subordinated to that of agents and instances alien to his interests.

An incomplete, invalid creature, subject to the ups and downs of the criteria that each of the representatives of the governing body has. To the interpretation that each of them gives to the laws and regulations. To the politicking, idiosyncrasy, indifference and "functional aquaculture illiteracy" that has prevailed for many years in many officials.

A lot of theory. A lot of studying. A lot of reading. A lot of envy, but nothing to act to consolidate the activity and take it to the place it deserves and that the country demands.

With each change of government, with each change of the body of affiliation, with each change of the name of the governing body, with each change of minister, with each change of anything, Venezuelan fish farming remains stagnant, and while worldwide the evident and imperative need to generate alternative fishing resources to traditional extraction activities has been verified, the country produces less and less fish biomass every day, thanks to multiple obstacles and poor and ill-advised policies and efforts.

For all this, Venezuela requires a National Aquaculture Plan that transcends a particular management, which covers all modalities, alternatives, species, acting and regulating the entire production process and the entire production and marketing chain. A Plan that serves us all.

For the year 1990 we presented, approved, and published the First National Aquaculture Plan which contemplated as basic objectives the generation of feed, the generation of jobs, promote regional development and the capitation of currencies, all of them under guidelines of policy of scope social, economic, technological development, engineering, infrastructure, administrative coordination and simplification and aquaculture nesting.

The objectives set were not achieved, and the avalanche of political changes that took place in the country, helped the efforts to be diluted and lost.

In the fairly recent past we sent our governing body a proposal for the formulation of a II National Aquaculture Plan, and the support required for its review, correction, concretion and support was requested from the FAO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, but from the same government (Vice Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture) its evaluation and the support that FAO offered was rejected.

This new proposal contemplated All this grouped into four (4) Strategic Programs.

All this toast on the entire production process and on the entire marketing chain through the application of seven (7) Strategic Projects:

The diagnoses, experience, and expertise to develop an efficient, sustainable and successful fish farming activity exist, so you do not have to start any process from scratch. We did it years ago with FAO, and through basic techniques of strategic planning and analysis of alternatives, in a short time comprehensive proposals for fish management were designed for some regions of the country.

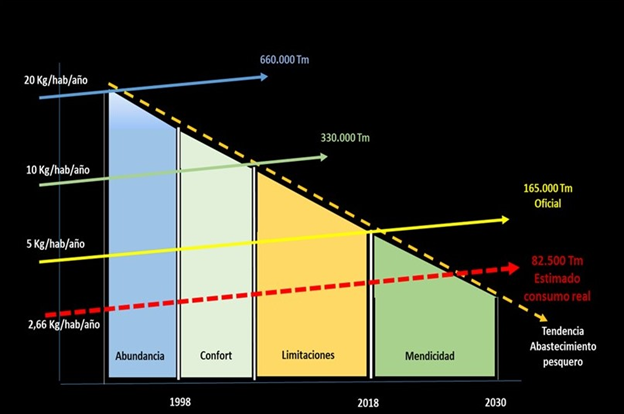

Figure 1 Trend of national per capita consumption of fish biomass in the period 1998 – 2030 for Venezuela, estimated based on official reports.

It is our right to claim probity, honesty, and technical and professional neatness in both the public and private sectors. Demand actions, regulations, programs and projects in accordance with the requirements and times that the country is experiencing, updating, modernization and strict compliance with the laws and decrees that govern the matter.

Fish farming has as much potential as a foreign exchange generating activity as shrimp farming, but undoubtedly has much more potential than it does as an activity that generates fishing biomass for the daily consumption of the population and can constitute a solid support for the development of food programs for social purposes that the same government develops.

Finally, because of the visit of a shrimp sector mission to Russia in the recent past, great possibilities have opened up for the export of fish (especially tilapias). Now we must produce them.

Recently, a new minister has been appointed who, without being directly linked to the fishing sector, seems willing to make decisions, correct mistakes and mistakes of the past and promote activity as a tool for capturing the foreign currency that the country so many needs.

In a few days he achieved a presidential pronouncement on the massive cultivation of tilapias in the country that for so many years has been hindered. In a few days, efforts were initiated to evaluate the cultivation of tilapia in some reservoirs such as the Uribante/Caparo until now vetoed for aquaculture use, and in a few days strategic sources of financing appeared that until yesterday were unknown and authorized the cultivation of tilapia to large shrimp conglomerates in the country. We hope that this authorization will be extended to the rest of the national fish farmers, many of whom keep their lagoons dry pending the improvement of the situation.

It is necessary that this be carried out in the most transparent and accurate way possible and that no mistakes are made to regret.

Hopefully this opening will reach all levels and corners of the country, and it will be worth integrating most fish farmers horizontally by providing them with support (assistance, fry and food, for example) in exchange for the arrival of their biomass as many sectors of agribusiness have been doing over time. That will motivate and strengthen them, accelerating national fish production while minimizing hunger and poverty.

Finally, we hope the new minister will allow himself to listen to the recommendations that hundreds of professionals in the area are willing to offer to promote the activity.

None.

None.

©2022 Robaina. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.