Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 3

1Assistant Professor Gynecology, Gitam Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, India

2Assistant Professor, Gitam Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, India

Correspondence: Vijayalakshmi Chandrasekhar, Assistant Professor Gynecology, Gitam Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Visakhapatnam, India

Received: February 17, 2017 | Published: February 21, 2017

Citation: Chandrasekhar V, Rao JVN (2017) A Case of Gartner’s Cyst of the Vagina. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 7(3): 00259. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2017.07.00259

Gartner’s cysts, sometimes incorrectly referred to as vaginal inclusion cysts, are the most common benign cystic lesions of the vagina. They represent embryologic remnants of the caudal end of the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct.1 Gartner’s ducts are found in about 25 percent of adult women. Almost one percent of these ducts evolve into Gartner’s duct cysts.2

A 36 year-old woman, gravida 2 para 2, consulted our hospital outpatient department with complaints of a vaginal mass since 8 months. She gave no history of any menstrual irregularity, vaginal discharge, urinary retention, incontinence, fever, injury, and backache, abdominal or pelvic pain, excepting for some discomfort during sexual intercourse. Per speculum examination showed a large cyst 6x7x5cm in size, originating from the proximal vagina. It was pedunculated, fluctuant, non tender, mobile, cystic-like and protruding from the right anterolateral vaginal wall (Figure 1). The rest of the genitourinary and abdominal systems were without notable abnormalities and pathology. Her laboratory routine investigations were within normal limits and urinalysis and pregnancy tests were negative. Ultrasound showed a large anechoic fluid filled cyst of 6x7 cm distinct from the uterus. Sagittal transvaginal scanning (Figure 2) showed up a well- defined cystic mass on the right anterolateral aspect of the upper vaginal vault adjacent to, yet clearly separate from, the cervical tissue. Transverse transvaginal scanning confirmed these findings and delineated the cyst lateral to the uterine cervix on the right side (Figure 3). At this stage, a provisional diagnosis of a Gartner duct cyst was considered. Both maternal kidneys appeared normal.

Surgical excision was done in lithotomy position under epidural anesthesia. Due to dense adhesions between the cyst wall and the vagina, complete excision was not possible and hence marsupialization of the remaining cyst was done. Fluid from the cyst and tissue from the cyst wall was sent for histopathological examination. This was reported as non mucin secreting low columnar and cuboidal epithelium, consistent with the diagnosis of Gartner’s cyst. Patient did not have any complaints at three-month post-operative follow-up.

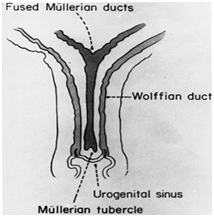

In a female fetus the mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts begin to develop at 20-30 days of gestation. The Müllerian ducts develop from the paramesonephric ducts, growing caudally on each side. By the 35th day after fertilization the lower part of the ducts change direction and grow towards the midline, where they meet and fuse with each other and then grow caudally once again. By the 65th day they complete fusion and their medial walls gradually disappear to form a single hollow tube (Figure 4). The mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts degenerate and remain as a vestigial system in females.3 Sometimes, the remnants secrete fluid and cause dilation of surrounding cells, becoming a Gartner's duct cyst, most often during and late adolescence. Classically, the cysts are solitary, unilateral, less than 2 cm in diameter, and are located in the submucosa of the anterolateral vaginal wall of the proximal third of the vagina.4

Figure 4 Genital tract in 10-week fetus.

(Remnants of Wolffian duct result in Gartner's duct cysts.)

Gartner's duct cysts are generally asymptomatic, and most commonly diagnosed upon routine gynecologic examination. Patients can complain of a skin tag, dysuria, pressure, itching, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, or a mass protruding from the vagina when surgical excision can be considered.5 If large enough to cause obstetrical complications like outlet obstruction, the cyst can be drained to facilitate delivery. Mesonephric duct remnants usually do not present any clinical dilemma. However, if the cellular lining remains active, it may lead to cystic lesions that may cause pain or torsion of the adnexa.4

MRI is useful to differentiate a Gartner’s duct cyst from other pathologic considerations and structures, The cellular elements can be examined and usually composed of non-mucin secreting low columnar or cuboidal epithelium. This may not be, however, necessary in clinical practice. Differential diagnosis can include Bartholin's gland cyst or abscess, prolapsed urethra, prolapsed uterus, vaginal wall inclusion cyst, endometriosis, leiomyoma, sarcoma botryoides, malignant mass, Skeine's gland cyst, or abscess and ureterocele. Malignant transformation is exceptionally rare.6 Patients may be discharged with gynecologic follow-up.

Though they are usually isolated, Gartner duct cysts can also be associated with abnormalities of the metanephric urinary system or part of the Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome associated with renal agenesis, ipsilateral renal dysplasia and cross fused ectopia. Because the ureteral bud also develops from the Wolffian duct, it is not surprising that Gartner duct cysts have been associated with ureteral and renal abnormalities, including congenital ipsilateral renal dysgenesis or agenesis, crossed fused renal ectopia, and ectopic ureters.7–11 In addition, associated anomalies of the female genital tract, including structural uterine anomalies like ipsilateral müllerian duct obstruction, bicornuate uteri, and uterus didelphys and diverticulosis of the fallopian tubes, have been described.12

When located in the paravaginal space, giant Gartner's cysts can be misdiagnosed as pelvic masses or broad ligament cysts and result from ectopic communication with the ureter or cervix.13 There are some reports of Gartner’s duct cyst diagnosis during transabdominal and transrectal ultrasonographic examination.14 3 dimensional endovaginal and endoanal sonography can be diagnostic in doubtful cases.15 Ultrasonographic depiction of cystic structures within the uterine cervix are not uncommon, and these usually are considered to represent nabothian (retention) cysts, reported to range between 6 and 20 mm in diameter and located eccentric to the cervical canal. Gartner duct cysts may occur in the close vicinity to the uterine cervix or eccentric to the cervical canal. These may prove a diagnostic challenge with the transabdominal ultrasonographic approach, especially with regards to small, isolated cysts. With transvaginal ultrasonography, the transducer is placed in immediate proximity to the cyst and cervix, enabling accurate diagnosis and clearly differentiating between Gartner duct and nabothian cysts. Similarly, transrectal ultrasonography may be useful in the assessment of vaginal disease and diagnosis of Gartner duct cysts. Nevertheless, transvaginal ultrasonography appears a more direct imaging modality for vaginal and cervical lesions. The clinical importance in differentiating between Gartner duct cysts and cervical inclusion cysts is important as the former can be associated with ureteral, renal, and structural female genital tract anomalies, some of which may require surgical treatment. Enhanced ultrasonographic imaging and clarity of a Gartner duct cyst can be obtained using the transvaginal USG when compared to the transabdominal approach.16 Below the levator plate, localizing is best done by magnetic resonance imaging. Recurrences of giant cysts tend to be multiloculated when they are best managed by perioriodic surveillance, schlerotherapy and marsupialization into the peritoneal cavity.

The differential diagnosis of cystic structures located in the upper vagina and uterine cervix includes nabothian cysts, Gartner duct cysts, and, rarely, specific obstructed müllerian duct anomalies (usually uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina).17–19 The latter are not true cystic lesions and usually contain echogenic contents (obstructed menstrual debris), and patients with these lesions commonly have cyclic symptoms (primary dysmenorrhea) whereas patients with nabothian cysts or Gartner duct cysts are usually asymptomatic. In infants with pelvic cysts, distension of the vagina with normal saline can confirm that the mass lies in the vaginal wall. Adenosis of the vagina must be considered if there a history of antenatal exposure to synthetic hormones is elicited. If the mucosa stains normally with Lugol's solution, one can exclude the diagnosis of adenosis. Mucin containing paramesonephric duct cysts have a secretory epithelium lining resembling endocervix or fallopian tube, suggesting a Müllerian origin and occur anywhere in the vagina. Following surgical procedures such as episiotomy, colporrhaphy, or trauma, including childbirth, inclusion cysts of the vagina can result from mucosa trapped in the submucosal area. These contain keratin and squamous debris and show foreign-body reaction and inflammation surrounding the cyst. They can become symptomatic as the cysts enlarge. Endometriosis of the vagina can develop at the site of a previous surgery or as primary implants. Endometriotic implants of the posterior cul-de-sac and may eventually erode or grow into the vaginal mucosa and feel nodular in the posterior vaginal fornix. On colposcopy, these implants may appear dark blue or brown or even white if associated with fibrosis. Chocolate-colored material representing old hemorrhage and dense fibrosis may be obtained at biopsy. Histological examination will show endometrial glands and stroma.20

None.

There is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2017 Chandrasekhar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.