International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8084

Review Article Volume 8 Issue 4

1Department of Radiotherapy, GenesisCare UK, London

2Department of Radiotherapy, Radiologie am Stern, Essen

3Department of Dermatology, CHUV, Switzerland

4St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guys Hospital, London

5Department of Dermatology, St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne

Correspondence: Richard Shaffer, GenesisCare Radiotherapy Department, Cromwell Hospital, 164-178 Cromwell Road, Kensington, London SW5 0TU, UK , Tel +44 (0)808 1565900

Received: November 24, 2021 | Published: December 17, 2021

Citation: Shaffer R, Seegenschmiedt MH, Panizzon R, et al. Systematic review of radiotherapy for cutaneous psoriasis: bringing an old treatment into the modern age. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2021;8(4):194-202. DOI: 10.15406/ijrrt.2021.08.00314

Background/Objectives: Radiotherapy has been used successfully over decades to treat psoriasis but has fallen out of favour more recently in many countries. Whilst novel biologic treatments for psoriasis can be very effective in moderate-to-severe and refractory-site disease, they are costly and may have significant side-effects including potential carcinogenesis.

Methods: A structured search was conducted for papers looking at the effectiveness of radiotherapy for cutaneous psoriasis. The findings were narratively synthesized.

Results: Most studies concluded that radiation has a role in the treatment of patients with psoriasis, particularly in difficult to treat areas such as the nails, scalp, hands and feet. Response rate for scalp psoriasis was 78-89%, with a durable response at 6 months in 31-53%; Hyperkeratotic psoriasis of the palms and soles had a response rate of 73-94% with durable responses at 1.6 - 4 years in 36-50%. There was weaker evidence for the treatment of nail psoriasis and palmo-plantar pustulosis.

Conclusions: Radiotherapy should be considered as a useful adjunct to topical and systemic treatments for psoriasis, although overall there remains a need for further research.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Radiotherapy, Grenz rays, superficial X-rays, Benign, Electrons

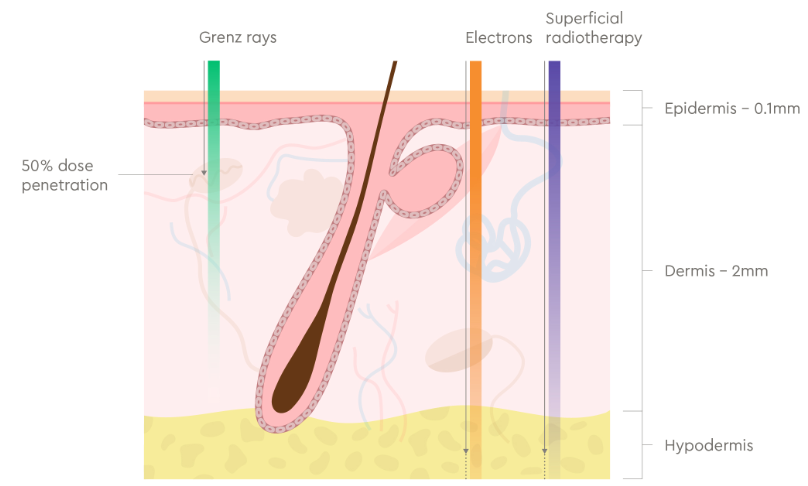

Radiotherapy is delivered with X-rays or particles and different energies which allow the deposition of the dose at varying depth (Figure 1-2). Although primarily used for the treatment of cancer (with doses of 50-70Gy), many benign conditions can be treated with low to intermediate doses of radiotherapy (3 - 30Gy) to good clinical effect.1 These include skin conditions such as keloid scars,2 DSAP3 and Darier’s disease,4 The radiation depth-dose characteristics can be made use of to target cells involved in disease whilst protecting deeper structures. Despite being rarely used in the UK, radiotherapy is used routinely in other European countries.5,6 A 2001 Scandinavian survey of Danish National Psoriasis Association members found that 70.7% of Danish psoriasis patients had been treated with grenz-ray radiotherapy.7

Figure 1 Cross-section of skin showing typical structures and skin layers at depth.

Grenz rays (10 – 20 kV energy range) are attenuated to half their dose at 0.5 -1.0mm and are almost completely absorbed within the first 2mm of the skin. Superficial X-rays (30 – 100 kV) and electron radiotherapy (3 – 6 MeV) can penetrate beyond the dermis.

Note: Depths of skin layers can vary considerably between different body sites.

Figure 2 Depth-dose characteristics of different types of radiation used to treat skin disease: When radiation passes through skin and underlying tissues, the radiation is absorbed so that the dose is attenuated with depth in a pattern that is characteristic of the modality and energy of the radiation.

Note: Electron depth-dose is shown assuming placement of tissue-equivalent bolus material on the skin surface in order to increase the effective dose to the skin and reduce penetration depth.

Grenz rays are very low-energy X-rays at 10-12kV. They were first discovered in 1923 and termed ‘grenz’ rays as it seemed their biological effects were on the border between those of UV radiation and traditional X-rays (grenz is border in German). The half-value depth of grenz rays is 0.5mm,8 making them ideal for treating psoriasis because the pathogenic processes mainly occur in the epidermis and dermo-epidermal junction, at only 0.1-0.3mm deep.9 Grenz rays have been used to treat psoriasis for decades. Their twofold mechanism of action includes antimitotic activity on the epidermis and modulation of dermal inflammation via action on Langerhans cells.10,11

Another radiotherapy type of relevance to psoriasis patients are superficial X-rays, which are delivered at the 20-100kV energy range, which penetrate more deeply than grenz rays. The half-value depth of 80kV superficial X-rays is approximately 10mm allowing treatment through normal skin and into subcutis, or perhaps through thickened psoriatic nails or hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis.

Similarly, particulate beams of high-energy electrons can also be used to treat psoriasis and can penetrate more deeply than grenz rays. Electron beams have the advantage of being delivered by machines widely available in the UK.

This manuscript systematically reviews the use of radiotherapy for the treatment of psoriasis, a common, painful, and disfiguring inflammatory skin disease.

Search strategy

A structured search was conducted in PubMed and Cochrane electronic databases in March 2020 identifying clinical reports published from 1958 - 2016. The search did not identify any papers published from 2016 - 2020. The search was conducted again in January 2021 however this did not identify any further relevant studies. Reference lists from included articles were cross-checked to identify additional papers. Details of search terms used are outlined in the appendix.

All original studies published in English, with full text available, on the use of radiation for the treatment of psoriasis at different body sites and using a variety of types of radiation were included. Studies could include patients with or without prior history of radiotherapy or surgery. There were no limits in relation to type of study, age of participants or year of publication. All identified studies were independently assessed by two authors (RS, JF) for eligibility based on their title and abstract. Where uncertainty remained, full-text was reviewed.

Extracted data included: type of radiotherapy, dose fraction, interval and total dose, number of patients, outcomes and type of study. The findings were narratively synthesized.

General observations

Of the eleven key primary research studies, seven involved grenz ray therapy with or without topical corticosteroids,6,12-17 two related to treatment using electrons18,19 and two involved superficial radiotherapy.20,21

Most studies had only small numbers of psoriasis patients (n = 3 - 67), with the vast majority being adults. Efficacy was reported up to 4 months post treatment was reported in most studies, with a few prospective studies14-16,18,20 reporting longer follow-up. Few studies used validated outcome measures or assessment criteria.

The highest level of evidence is a 2013 Cochrane systematic review on nail psoriasis.5 This review identified three studies which looked at the safety and effectiveness of radiotherapy specifically for the treatment of nail psoriasis. Several non-systematic reviews and primary research studies were also identified.

Most studies concluded that radiation has a role in the treatment of patients with psoriasis, particularly in difficult to treat areas such as the nails, scalp, hands and feet (Table 1).

|

Local Site |

Author (Year) |

RT Type |

RT Concept |

Number of patients |

Type of study |

Main results |

|

General |

Brodersen (1981) |

GRT |

1.5Gy x 3 (weekly) = 4.5Gy |

20 |

Double-blind trial of steroids +/- grenz: paired body sites – RT vs sham RT |

· Patient assessed improvement on one side: o At end of treatment: 10/20 (50%) favoured grenz, 0/20 favoured non-grenz, 10/20 (50%) had no preference o At 2 weeks: 12/20 (60%) favoured grenz, 6/20 (30%) no preference |

|

Harber (1958) |

GRT |

2Gy x NK (weekly) = NK |

67 |

Three areas in single individuals treated with grenz, SXT (50kV) or control and compared |

· Grenz and SXT better than controls in smaller lesions at days 14&21, but not at days 7&28 · No significant difference between RT and controls in lesions > 300cm2 |

|

|

Nails |

Kwang (1994) |

ERT (7MeV) |

0.75Gy x 8 (weekly) = 6 Gy |

12 |

Non-blinded comparison: RT to one hand vs other not treated |

· 3 months response: marked 1/12 (8%), moderate 2/12 (17%), slight 6/12 (50%), none 3/12 (25%) · 6 months – marked 0/12, moderate 1/12 (8%) · Significant improvement in treated hand vs control hand at 3 months but not at 6 or 12 months |

|

Yu (1992) |

SRT (90kV) |

1.5Gy x 3 (twice-weekly) = 4.5Gy |

8 |

Double blinded controlled (RT to nails of one hand vs other not treated) |

· Small but statistically significant improvement in visual score of treated nails compared with baseline · Significant improvement compared with non-treated nails at 10 and 15 weeks but not at 20 weeks |

|

|

Lindelof |

GRT |

5Gy x 10 (weekly) = 50Gy |

22 |

Double blinded controlled (RT to nails of one hand vs other not treated). Crossover of non-treated hand at 10 weeks. |

· 10 weeks response: complete 1/22 (4.5%), slight 7/22 (32%) · Significant improvement compared with non-treated nails · 6 months: moderate 2/22 (9%), slightly worse 2/22 (9%) |

|

|

Fenton (2016) |

GRT |

3 - 7Gy x 4 -13 (weekly) = NK |

27 |

Retrospective |

· 6-8 weeks response: complete 1/27 (4%), marked 7/27 (26%), minimal 8/27 (30%), none 11/27 (41%) |

|

|

Scalp |

Fenton (2016) |

GRT |

4-6 Gy x 3 - 12 (weekly) = NK |

36 |

Retrospective |

· 6-8 weeks response: complete 13/36 (36%), marked 19/36 (53%), minimal 3/36 (8%), none 1/36 (3%) · 8/36: complete/marked response at latest follow-up (1-44 months) |

|

Johanssen (1987) |

GRT |

4Gy x 6 (weekly) = 24Gy |

17 |

Double blinded controlled (steroids + RT to one side of scalp vs no RT to other side of scalp). |

· 3-6 month response: Almost complete healing 15/17 (88%) · Reduction in severity score from 12 pre-treatment to: o Steroid + Radiotherapy = 2.5 o Steroid alone = 7 · 6 months response 8/15 (53%) still healed |

|

|

Lindelof (1989) |

GRT |

4Gy x 6 (weekly) = 24Gy |

37 |

Randomised trial grenz vs grenz + steroids |

· Healing in 29/37 (78%) overall · Reduction in severity score from 9.1 to 1.7 and 10.4 to 1.6 in grenz and combination groups (no significant difference in reduction in severity) · At 6 months 9/29 (31%) remained healed |

|

|

Hands and feet Hyperkeratosis |

Sumila (2008) |

SRT (43-50kV) |

0.5—1Gy x 5-13 (twice-weekly) = 2.5 - 13Gy |

28 (88 treated sites) |

Prospective case series |

· End of radiotherapy, response (regions, patient-rated): complete 39/88 (44%), better 44/88 (50%), stable 5/88 (6%) · Median 20 months response: complete in 36% |

|

Fenton (2016) |

GRT |

4 - 8Gy x 4 - 10 (weekly) = NK |

22 |

Retrospective |

· 6-8 weeks response: Complete 7/22 (32%), marked 9/22 (41%), minimal 2/22 (9%), none (4/22 (18%) · At 4 years follow-up, 50% still had complete or marked response |

|

|

Palmo-plantar pustulosis |

Fairris (1984) |

SRT (50kV) |

1Gy x 3 (3-weekly) = 3Gy |

9 |

Double-blind: paired hands/feet – RT vs sham RT |

· 1/9 (11%) patients responded to grenz during treatment |

|

Lindelof (1990) |

GRT |

4Gy x 6 (weekly) = 24Gy |

17 |

Double-blind: paired hands/feet – RT vs sham RT |

· Better symptom improvement with grenz in 13/15 (87%) · Response “moderate”: o No complete clearances o Severity score 10 vs 15 (RT vs sham RT) |

|

|

Fenton (2016) |

GRT |

5Gy x 6 – 8 (weekly) = 30-40Gy |

9 |

Retrospective |

Marked improvement in 3/9 (33%) |

Table 1 Summary of former clinical studies of radiotherapy in psoriasis

Nail psoriasis

In the 2013 Cochrane systematic review5 three radiotherapy studies were identified.14,18,22 Kwang et al.18 treated 12 patients with symmetrical fingernail psoriasis with electron radiotherapy to one hand and no treatment to the other. At 3 months one patient had a marked response and two had a moderate response. However, by 6 months, no patients maintained a marked response and one still maintained a moderate response.

Yu et al.22 treated 8 patients with severe psoriatic fingernail dystrophy. One hand was treated with 1.5 Gy given every 2 weeks to a total dose of 4.5 Gy. Sham radiotherapy was delivered to the other hand. Baseline and response outcomes were collected using a visual assessment (scale 0-12), as well as nail growth rate and thickness. There were statistically significant but clinically minor differences in visual scores at 10 weeks (4.4 vs 5.4) and 15 weeks (4.6 vs 5.5) but these were not maintained at 20 weeks.

Lindelof et al.14 followed up 22 patients in a double-blinded controlled trial with grenz rays with 5 Gy per week for 10 weeks to the fingernails of one hand. Sham radiotherapy was given to the other hand. At 10 weeks they found a complete response in 1/22 (4.5%) and a slight partial response in 7/22 (32%), although there was a significant improvement compared with the non-treated nails.

Fenton et al. reviewed grenz ray treatment results in 27 patients with nail dystrophy (mainly psoriatic) after grenz ray treatment.6 They found initial outcomes at 6-8 weeks of clearance in 1/27 patients (4%), marked improvement in 7/27 (26%), minimal improvement in 8/27 (30%) and no change in 11/27 (40%). Three patients still had clearance or marked improvement at their most recent follow-up at between 4, 36 and 53 months.

Scalp psoriasis

Three studies looked at radiotherapy for scalp psoriasis.6,15,16 Fenton et al. followed 36 patients who had received grenz rays.6 They demonstrated clearance in 13 patients (36%), marked improvement in 19 patients (53%), minimal improvement in 3 patients (8%), and no change with 1 patient (3%). Eight still had clearance or marked improvement at the most recent follow-up (range 1-44 months).

Johannesson et al. treated 17 patients with symmetrical scalp psoriasis15. One side of the scalp was treated with topical steroids and grenz rays and the other with sham irradiation and topical steroids. With the combination treatment, 15 of 17 patients showed almost complete response, with 8 of 15 healed patients still clear of disease six months after completing therapy.

Lindelof et al randomised 40 patients with scalp psoriasis to grenz rays alone or grenz rays combined with a topical corticosteroid.16 4 Gy were given on six occasions at weekly intervals. Of the 37 patients who completed the trial, 16/19 (84%) in the grenz ray group and 13/18 (72%) in the combination group cleared. The remission time did not differ significantly between the two groups. Of the patients with clearance, 31% remained clear at six months.

Hyperkeratotic Psoriasis/Eczema of palms and soles

Sumila et al.20 treated 22 patients diagnosed with hyperkeratotic eczema and six with hyperkeratotic psoriasis of palms and/or soles twice a week either with 1 Gy (median total dose 12 Gy) or 0.5 Gy (median total: 5 Gy). They used superficial X-rays at 43-50kV. A total of 88 body sites were treated. Eight symptoms, including itching, pain and cracking were scored from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe), giving a possible sum score of 0-24. Patients’ ratings of the results were also recorded. The median sum score was 15 (6–23) before radiotherapy, 2 (0–16) at the end of radiotherapy, and 1 (0–21) at a median of 20 months follow-up. Patients reported complete remission in 39/88 regions (44%) and incomplete response in 44/88 (50%). Complete response (i.e. score 0) was durable in 36% of patients at median 20 months follow-up.

Fenton et al.6 treated 22 patients with hand/foot eczema/psoriasis with grenz rays, generally with 4-8Gy per fraction for 4-10 treatments. At 6-8 week follow-up they recorded responses that were complete in 7/22 (32%), marked in 9/22 (41%), minimal in 2/22 (9%), none in 4/22 (18%). Half of the patients still had complete or marked improvement at 4 years after treatment.

Palmoplantar pustulosis

Three studies6,17,21 looked at the effects of radiotherapy on palmoplantar pustulosis. Fairris et al. examined nine symmetrical paired sites of persistent palmoplantar pustulosis in three patients.21 The study was double-blinded where one site was given a dose of conventional superficial X-ray therapy (1 Gy) and the other site received a placebo dose. The dose (or sham dose) was administered three times at intervals of 21 days. Only one patient with palmoplantar pustulosis on the hands remitted during the six weeks of X-ray therapy. The remainder showed no improvement on treated or untreated sites. The authors concluded that this trial indicates that conventional superficial X-ray therapy has little or no therapeutic effect upon palmoplantar pustulosis.

Lindelof et al. conducted a double-blind placebo-controlled study of 15 patients with moderate to severe palmoplantar pustulosis.17 They were treated with 4 Gy of grenz rays, given weekly on six occasions, and patients were scored on five symptoms from 0-5, with a potential total composite score of 25. Pre-treatment scores was 16/25 in both groups, which was reduced at the end of treatment to 10/25 in the grenz ray group, compared with 15/25 in the placebo group, with a greater improvement in the hand/foot receiving grenz ray treatment was seen in 13/15 patients (87%). The response was considered “moderate”, with no lesions healing completely.

Fenton et al.6 reviewed outcomes of nine patients treated with Grenz rays for palmoplantar pustulosis. Although clearance was never achieved; they report marked improvement after three courses. This was sustained for three months after treatment. However only one patient still had clearance at the most recent follow-up.

Radiotherapy dosage

A typical course of grenz rays was 4 Gy per week for a total of 4 - 8 weeks.6,15-17 In the most recent study, dose per fraction ranged from 0.5 to 8 Gy, depending upon pathology, body site and skin thickness. The number of fractions per treatment course ranged from 3 to 12, and tended to be set empirically according to disease response and toxicity. Dose was increased on areas of scalp covered with thick hair due to partial absorption of radiation by hair.6 Table 2 summarises historical grenz doses according to disease location.

|

Location of treatment area |

Dose per fraction |

Number of treatment sessions |

Total dose |

|

4-6 Gy |

6 |

Not stated |

|

|

Hyperkeratosis of hands and feet6 |

4-8 Gy |

4-10 |

Not stated |

|

5-6 Gy |

6-8 |

< 50 Gy |

|

|

3-7 Gy |

4-13 |

< 50 Gy |

|

|

Genital Area / Groin / Perianal |

0.5-0.8 Gy |

5-8 |

3 – 6 Gy |

Table 2 Historical grenz ray doses

In the studies above, superficial X-rays and electrons individual doses were typically 0.5 - 1.5 Gy, with total doses of 4.5 to 12 Gy. This represents a much lower fraction size and total dose than was administered in the grenz ray studies, where the average individual dose was 4 – 8 Gy, with typical total doses of 20-40 Gy. This is due to the shallow penetration of grenz rays, which leads to a large reduction in the volume of tissue irradiated with grenz rays compared with superficial X-ray or electron treatment. This in turn leads to sparing of radiotherapy-associated side-effects with grenz rays compared with more penetrating radiation modalities.

There are no studies in the literature comparing grenz rays with superficial X-rays or electrons. There is also minimal information comparing clinical responses to different doses within the individual radiation modalities.

Lindelof et al. reported the standard grenz ray regimen followed at Karolinska in Sweden.23 They used the following limitations: Cumulative lifetime dose should be <100Gy; Dose was fractionated (generally at one treatment per week for 4-6 weeks); the suggested interval should be ≥ 6 months between courses; the dose was adapted for different body sites and pathologies, for instance 0.5 Gy once a week for 4-6 weeks for thicker lesions such as lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (vulva), and 4 Gy once a week for 4-6 weeks for shallower lesions such as scalp psoriasis.

The American Association of Dermatology guidelines suggested that a typical treatment regimen of grenz therapy involves administration of 2 Gy per session at weekly intervals up to a total of 8 - 10 Gy. After six-month rest, treatments could be repeated up to a total cumulative dose of 50 Gy.24 This recommendation can be traced back to a paper in 1960,25 and the author admits that these limits are “arbitrary” and “conservative”. Indeed, Lindelof believed that provided a 6-month rest was given, this dose schedule could be followed “ad infinitum”.10

Adverse events

Due to the very superficial penetration of grenz rays, specific toxicities such as hair loss should be avoidable with grenz rays, as the radiation does not penetrate sufficiently deeply to affect hair follicles. The lack of radiation penetration, and therefore reduced toxicity, allows higher total doses to be administered. A non-systematic review by Warner et al report that the most common potential side effects of grenz ray therapy are relatively minor; these include erythema (typically asymptomatic) and dyspigmentation (usually temporary).26 However, pigmentation was the only observed adverse effect of grenz ray therapy in the study by Fenton et al.6 and this is in accordance with previous findings.14,27

In contrast, higher energy X-rays (soft and superficial, 20-100kV) penetrate more deeply, leading to a higher volume of irradiated tissue, so that the dose limits are held to be much lower e.g. 12Gy.28 One study on superficial radiotherapy and one on grenz ray therapy assessed adverse effects, but did not report any.17,22 However, since superficial X-rays and electrons do penetrate deeply enough to affect hair follicles, a different toxicity spectrum would be expected, which at higher doses could include hair loss, radiation dermatitis and scarring.

These factors are also important to consider in discussions about repeating treatments and cumulative lifetime dose limits.

Risk of radiation-induced cancers (RIC)

The risk of RIC depends on how wide an area is treated, the depth of treatment, what tissues are in the radiation volume, and the age of the patients (with younger patients being more at risk than older patients). It is important to consider all these factors. An appropriate field size should be used so that normal tissue is not treated more widely than necessary. The appropriate radiation modality and energy should be selected so that target cells are irradiated whilst protecting deeper layers of tissue. Other structures should be shielded from unnecessary irradiation. In younger patients, the risk of radiation-induced cancers is higher, so that there should be a higher threshold for treatment per se.

With conventional therapeutic irradiation (i.e. not grenz rays) to intermediate doses of 3-50Gy, the lifetime risk of radiation-induced basal cell carcinoma has been estimated to be approximately 0.006% based on 100 cm2 of skin treated to a mean dose of 3Gy. Another report has suggested this risk to be ≤ 0.1% in a sun-exposed field and an order of magnitude lower in skin not exposed to the sun. It should be noted that all these figures are very much smaller than the spontaneous lifetime risk of BCC which is > 20%.29

A retrospective review of 14,237 patients who had received therapeutic doses of grenz rays for benign skin disorders, including psoriasis, used information from the Swedish Cancer Registry, although it should be noted that basal cell carcinomas were not registered.23 They found no excess risk of malignant melanoma, but found 39 non-melanoma skin cancers compared with the expected rate of 26.9, giving a relative risk ratio of 1.45. Interestingly, no malignancies were found in those who received a cumulative dose of at least 100Gy. Most patients who developed malignancies on grenz ray-treated areas had also received treatment with other carcinogens and immunosuppressants.

Radiotherapy is effective in the treatment of psoriasis. The strongest evidence for radiation treatment is for the management of scalp psoriasis, with a response rate of 78-89% and a durable response at 6 months in 31-53%. It also seems effective in the treatment of hyperkeratotic psoriasis of the palms and soles, with a response rate of 73-94% and durable responses at 1.6 - 4 years of 36-50%. There is weaker evidence for the treatment of nail psoriasis and palmo-plantar pustulosis. Overall there remains a need for further research.

Place in treatment pathway

Psoriasis treatment depends on disease severity, impact on quality of life and the presence of psoriatic arthritis and comorbidities. Current UK guidelines30 suggest a structured approach to psoriasis treatment. First-line treatments include topical corticosteroids and vitamin D. Second-line treatments include the phototherapies (NBUVB and PUVA) and systemic non-biological treatments such as methotrexate or ciclosporin. Subsequently, systemic targeted immunological therapies can be considered.

Although systemic therapies can be highly effective, the condition tends to recur after they are stopped, so long-term use with all its attendant costs is often required. Additionally, there are known risks associated with many systemic treatments for psoriasis, including teratogenicity, liver toxicity, bone marrow suppression, hematological and cutaneous malignancy, opportunistic infection and renal dysfunction.31

Radiotherapy involves a relatively small number of treatments but can result in a long-term response to treatment. Although the risk of radiation induced cancer remains, radiotherapy is not associated with organ toxicity or systemic immunosuppression. It may have a role in the treatment of patients not appropriate for systemic therapies, who do not tolerate them or who prefer to avoid them.

Some patients have localized psoriasis in so called “difficult to treat” areas (nails, palms, genitals, perianal skin, or scalp). Patients with disease in these areas may prefer radiotherapy as a localized approach for a localized problem.

Site-specific effects

When treating psoriasis of the scalp, none of the studies mentioned hair loss. With grenz rays, as there is no effective radiation penetrating beyond 2mm, alopecia is not expected as hair follicles are found in the deep dermis. Meanwhile, the difficult-to-treat lichenoid inflammatory scalp disorders involve the more superficial portion of the hair follicular unit, which would render radiotherapy favourable.

There can be considerable diagnostic overlap between hyperkeratotic eczema and psoriasis of the hands and feet both clinically and histologically.32,33 Initial treatment with topical steroids, emollients, PUVA phototherapy and oral retinoids are also similar for both conditions. Where differentiation is possible it is usually made on the background presence of clinical history and examination features of atopy, eczema or psoriatic disease elsewhere, as well as family history. Palmoplantar pustulosis, (another subtype of hand and foot psoriasis) is usually considered separately, as are atopic hand eczema, pompholyx eczema, contact dermatitis and irritant dermatitis. The classification of hand dermatitis remains challenging.34

The evidence is limited and less encouraging for palmar-plantar pustulosis. Lindelof and Fenton both suggest that this may be because the 0.5 mm depth of grenz radiation may be too superficial to treat thicker pustular lesions. However, the use of superficial X-rays at 50kV, which would be expected to penetrate more deeply, did not result in a good response, although a much lower dose of radiation was used and further studies are still needed.

Studies on nail psoriasis suffer from several methodological inconsistencies. Going forwards, they would benefit from accurate description of diagnostic features at baseline, a detailed account of participants' characteristics, clinical assessment via a validated assessment tool (e.g. NAS, NAPSI), patient-reported outcomes, and longer follow-up periods. Full nail regrowth can take six months so a follow-up time of less than this is too short to assess efficacy.5

Grenz vs other modalities

Grenz rays (10-12kV) are often used for the radiation treatment of psoriasis as the disease tends to affect the most superficial part of the skin. They are delivered as a patchwork of separate fields, which leads to both overlap (hot) and underdosed (cold) areas. Grenz rays are also not widely available outside of mainland Europe.

Where the target cells are located more deeply (e.g. thickened nails, or hyperkeratotic areas), the radiotherapy technique must be adapted. A higher energy (e.g. superficial X-rays) or different radiation modality (for instance electrons) may be used in order that the radiation penetrates further into the skin. Other radiation modalities such as VMAT (a modern megavoltage radiotherapy technique) could be used to treat complex volumes using a single complete technique in a quicker and more controlled way. These more penetrating techniques would be expected to have a different toxicity profile, as described above. Additionally, as they treat a higher volume of tissue they may lead to an increased risk of radiation-induced cancers.

Generally radiation doses used are approximately double with grenz rays compared to that used with superficial X-rays. For instance, superficial (20-100kV) X-ray doses for treatment of psoriasis of nails and scalp and chronic eczema would be 6-12 fractions of 1 Gy 2-3 times per week, whereas grenz would be dosed at 2Gy per fraction 2-3 times per week.28

New radiotherapy dose concepts

Historically, radiotherapy for benign skin conditions has been administered as a series of large doses of radiation given once per week. Modern radiotherapy for the treatment of cancer tends to be given as a series of small doses, with treatments delivered more frequently, generally daily. This allows time for normal cells to repair themselves between treatments, thereby reducing side effects.

With the resurgence in interest in radiotherapy for benign skin conditions, there is an opportunity to modernize the radiotherapy dose schedules in line with current radiation practice. Table 3 sets out the principles used to update the radiation dose concepts, and Table 4 proposes standardized dose-fractionations which vary according to site and radiation type.

|

1. Radiotherapy Duration a. Radiotherapy should be delivered over at least 2-3 weeks, with weekly physician evaluation b. Response to radiotherapy can be very rapid e.g. reduction of itching and plaques within 10-14 days. c. An assessment of tolerance and effectiveness should be made after 2-3 treatments (depending on the dose regime) in order to guide the total number of fractions to be delivered. The treatment may be discontinued if a complete response (or a good partial response) to treatment is observed. 2. Radiation Penetration a. The type and energy of radiotherapy is determined by the penetration needed to cover the disease to its full depth b. Higher energy radiation is needed for deeper penetration i. Grenz rays (≤ 10kV) for disease up to 1mm ii. Grenz rays (≤ 20kV) for disease up to 2mm iii. Superficial X-rays (≥ 30kV) or electrons (≥ 3MeV) for depth > 5mm c. Thick overlying hair necessitates an increase in radiation energy d. Before radiotherapy is started, the lesions should be pre-treated for 1-2 weeks to remove overlying scale with e.g. 10 – 20% salicyl oil (for body/extremities) or e.g. olive oil/rhizinus oil (for scalp). A vaseline occlusive bandage should be used for several days if the area is not sterile. e. Pre-treatment for palmar-plantar pustulosis with salicyl oil / vaseline occlusive bandage if not sterile: anti-inflammatory agents, cleansing with chlorhexidine. There should be a break of 4 weeks before starting RT, as combined treatment may lead to an over-reaction of skin and normal structures. 3. Dose per fraction a. More superficial treatments allow a higher radiation dose to be delivered, as a smaller volume of tissue is irradiated, with consequent lower radiation toxicity b. Therefore, generally half the dose per fraction is used for superficial energies (≥ 30 kV) compared with grenz rays (10-20 kV) 4. Fractionation (treatment frequency) a. For acute conditions, the dose should be given more frequently e.g. 3 – 5 times per week b. For chronic conditions, the dose should be given less frequently e.g. 1 – 2 times per week c. However, it may be reasonable to standardise the dose frequency at e.g. twice per week for all cases 5. Maximum doses a. Treatments can be repeated to the same body site, with maximum cumulative doses depending on various factors b. Structures susceptible to radiation toxicity include sweat glands (tolerance 15-20Gy, dry skin), nail bed (3-5 Gy, white or altered zones) c. Generally lifetime limits are higher for grenz than for higher energies, due to lower penetration leading to lower volume of tissue irradiated and therefore reduced toxicity d. Grenz ray limits allow two courses of 12Gy to be delivered, with an exceptional 3rd course allowed, so giving a lifetime limit of 36Gy e. A superficial X-ray limit of 24Gy allows at least 3 courses of 6 Gy, or exceptionally a fourth course f. There is an increased risk of radiation-induced cancer when treatment is given at a younger age i. For patients < 30 years – only treat in exceptional clinical situations as a last resort ii. 30-50y – treatment allowed in well-defined clinical situations iii. >50y – routine use up to accepted total dose limits g. There should be at least 6-12 months between courses of radiotherapy |

Table 3 Principles of new radiotherapy dose concepts

|

Location of treatment area |

Radiation energy |

Dose per fraction |

Frequency (per week) |

Number of fractions |

Total dose |

|

Scalp |

GRT |

1 - 2 Gy |

x 2 - 3 |

3 - 6 |

6 - 12 Gy |

|

Hyperkeratosis of hands and feet |

GRT |

2 Gy 1 Gy |

x 2 – 3 |

3 – 6 |

6 - 12 Gy |

|

Palmoplantar pustulosis (sterile) |

GRT |

1 - 2 Gy 0.5 - 1 Gy |

x 1-5 (acute x 3-5; chronic x 1–2) |

3 – 6 |

6 - 12 Gy 3 – 6 Gy |

|

Nails (subungual psoriasis) |

GRT (thin nails, females) |

1 - 2 Gy

|

x 2 - 3 |

3 – 6 |

6 - 12 Gy |

|

Exudative forms / abscess (all body sites) |

SRT |

0,3 – 0,5Gy |

x 2 – 5 (acute x 3–5, chronic x 2-3) |

5 - 10 |

5 - 10 Gy |

|

Chronic pruritis (genital, groin, |

GRT |

0.5 - 1 Gy |

x 2 - 3 |

5 – 10 |

3 – 10 Gy |

Table 4 Proposed standardized radiotherapy dose concepts with grenz rays and superficial X-rays

Notes:

GRT = 10-20kV

SRT = ≥ 30kV

Recommended RT technique: radiation target is lesion + 5 – 10mm safety margins

Why is radiotherapy not used more widely for psoriasis?

The use of radiotherapy for psoriasis and other benign skin diseases is widespread in mainland Europe, but is used less frequently in the UK, USA and Australia. There are several reasons for this: There are a growing number of alternative treatments for psoriasis. The equipment able to deliver low energy grenz radiation tends not to be widely available. The fact that radiotherapy is delivered by “Radiation Oncologists” may discourage the use of radiation for non-malignant conditions. The move away from radiotherapy for benign disease has also been driven by the nationally mandated allocation of radiotherapy resources to cancer, the fear of radiation-induced cancers and finally a lack of high-quality research in the field.

Radiotherapy is effective in the treatment of psoriasis, particularly of the scalp, hands and feet. The evidence supporting this practice is well-established, although by current standards the studies include low numbers of patients and unvalidated outcome measures. However, radiotherapy’s widespread use for psoriasis across northern Europe should not be ignored and there are enough data to warrant its further investigation. Radiotherapy should be considered as a third-line option in the treatment of psoriasis, particularly in “difficult to treat sites”. Carefully designed prospective studies, using validated outcome measures, would be a welcome addition to the literature.

Teresa Morris-Spicer for her help with the initial systematic review.

GenesisCare funded the initial literature search.

RS – consulting fees from GenesisCare and XStrahl, travel funding to learn new radiotherapy techniques

MHS – Chairman of Radiotherapy for Benign Diseases in German Society for Radiation Oncology

RP – nil

CT – nil

CB – GenesisCare consultancy agreement and member of skin research committee, board member of Skin Health Institute

JF – consulting fees from GenesisCare.

©2021 Shaffer, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.