International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8084

Case Report Volume 9 Issue 5

1Department of Radiotherapy, Instituo Nacional de Cancerología de México, Mexico

2Department of Hematology, Instituo Nacional de Cancerología de México, Mexico

Correspondence: José Ramiro Espinoza-Zamora, Department of Hematology, Nacional de Cancerología ciudad de México, Sanfernando 22 col Section XVI, Mexico City 14080, Mexico

Received: September 20, 2022 | Published: November 1, 2022

Citation: Salvador GT, Ramiro EZJ, Marco RC, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma with rectal activity in a patient with HIV: palliative treatment from the perspective of radiotherapy before the SARS-COV-2 contingency. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2022;9(5):141-143. DOI: 10.15406/ijrrt.2022.09.00338

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) are associated with an increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative disorders.

In 1997, Delecluse et al. presented a case series of 16 patients with Plasmablastic Lymphoma (LPB), an aggressive subtype of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLCGB), strongly associated with Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection with distinctive clinicopathological characteristics (lack of expression of CD20 and CD45, with strong reactivity for plasmacytic markers such as CD38 and CD138).

Reports and small case series have shown that HIV-associated OLP has a more aggressive clinical course and poorer survival rates than standard therapies. Therefore, this pathology poses a challenge in its treatment.

We present the case of an OLP with rectal activity in a patient with HIV, treated with radiotherapy during the SARS-CoV-2 contingency.

A 38-year-old male, homosexual, with a condition of more than 12 months of evolution, characterized by persistent proctalgia and rectal bleeding associated with a palpable lesion in the anal region, profuse night sweats, and weight loss of 8 kg in 2 months. He was approached by a proctologist who diagnosed a perianal abscess, drained the abscess, and resected the perianal lesion; however, after the surgical procedure, she continued with symptoms and the appearance of new tumor growth in the gluteal and perianal region. He went again to a proctologist who performed a rectosigmoidoscopy in which an intrarectal tumor was identified, a biopsy was taken with a histopathological report of Plasmablastic Lymphoma, CD138, MUM1, CD30, EBER-ISH, LAMBDA, Ki67 (80%), positive for neoplastic cells, CD20, CD3, BCL-2, BCL-6, KAPPA, CD10, negative. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 A AND B: Plasmablastic lymphoma, CD20, CD3, BCL-2, BCL-6, KAPPA, CD10, negative. C and D: LAMBDA and CD138 positive. Additionally MUM1, CD30, EBER-ISH, and Ki67 (80%) positive in neoplastic cells.

Given the histopathological diagnosis, it was decided to perform an ELISA test for HIV, with a reactive result. He was classified as HIV-C2 and started antiretroviral treatment with Tenofovir, Emtricitabine, and Dolutegravir.

On his first visit to the hematology-oncology service, a 6-cm exophytic lesion was found on physical examination at the perianal level, occupying 75% of the circumference of the rectal canal, with ulcerated areas, with no evidence of bleeding.

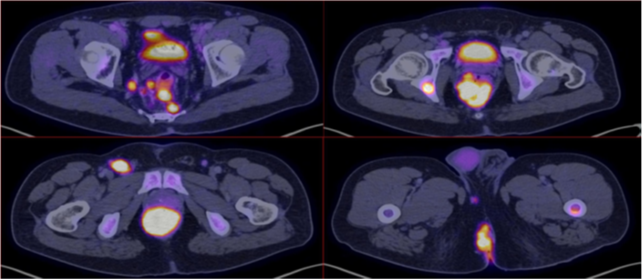

Positron Emission Tomography (PET-CT) was performed with evidence of tumor hypermetabolic activity at the rectal level (SUVmax 70.2), presacral and pararectal lymph nodes (SUVmax 46.6), inguinal (SUVmax 52.3), ischium, ischiopubic ramus (SUVmax 43.3), Liver (SUVmax 8.4). (Figure 2 &3)

Figure 2 E: Sagittal reconstruction of PET-CT with evidence of tumor hypermetabolic activity at the rectal level (SUVmax 70.2) FIGURES F and G: PET-CT coronal reconstruction with evidence of tumor metabolic activity at the rectal level (SUVmax of 70.2), ischium and femurs (SUVmax of 43.3).

Figure 3 Axial reconstruction with evidence of tumor hypermetabolic activity at the rectal level (SUVmax 70.2), presacral and pararectal lymphadenopathies (SUVmax 46.6), inguinal (SUVmax 52.3).

It was staged as CD IV-B and chemotherapy treatment with EPOCH (Etoposide, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone) was started, completing 4 cycles, showing the progression of the disease.

Second-line ICE (Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, Etoposide) was decided, without adequate clinical response after 3 cycles, so GEMOX (Gemcitabine, Oxaliplatin) was changed, showing progression data again after the end of 1 cycle. The fourth line of treatment with ESHAP (Etoposide, Methylprednisolone, Cisplatin, Cytarabine) was proposed. She received 1 cycle, with evidence of clinical progression. CyBORD (Cyclophosphamide, Dexamethasone, Bortezomib) was offered as the fifth option for systemic therapy. He completed 1 cycle.

Due to refractoriness to chemotherapy, secondary effects of the use of high-dose corticosteroids, and due to the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it was decided to send him to the Radiation Oncology service for palliative treatment.

In his assessment, he found significant proctalgia, inability to sit, constipation, and constant bleeding. He received a hypofractionated regimen of 25 Gy in 5 fractions, after which he showed adequate response to treatment with the involution of the exophytic tumor located in the perianal region, decreased pain, and rectal bleeding.

In his last evaluation by the Hemato-oncology service, 3 months after completing the radiotherapy treatment, without alterations for evacuation, without bleeding, with an area of induration less than 2 cm on the right buttock.

On July 20, 2020, PET-CT was performed without data on tumor activity in the rectal region or other areas with increased metabolism. Even on the day of the delivery of this work, the patient continues to be free of disease. (Figure 4)

The incidence of OLP is around 2.6% of all lymphomas according to some reported series. It is a recently described disease classified as an aggressive subtype of DLBCL with a plasma cell immunophenotype. There is no clear association between sex, race, or age; however, of interest, unlike the rest of HIV-associated lymphomas, OLP occurs in patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts above 50/µl.

HIV-associated OLPs occur more frequently in young men, in advanced stages, and with extranodal involvement. Expression of EBER, Ki67 greater than or equal to 80%, and negativity to the CD20 marker are common pathological characteristics in this neoplasm. They are mainly located in the oral cavity, but they can appear in other locations: gastrointestinal involvement, skin, lung, paranasal sinuses, rectum, and anal canal, less frequently.

Computed tomography is the most commonly used method for the diagnosis of lymphomas due to its availability and relatively low cost; however, other tools such as PET-CT can provide greater certainty to determine the extent of the disease in these patients. In both modalities, the presence of a homogeneous mass concentrically infiltrating the rectum, with or without occlusion of the lumen, is the most common aspect of intestinal involvement in lymphoma.

Despite antiretroviral therapy, patients with OLP associated with HIV have a poor prognosis, with mean overall survival of 11 and 6 months, respectively, without finding a trend towards improvement with more intensive chemotherapy regimens or additional interventions such as surgery and/or radiotherapy, finding the use of the latter, in 13-20% of cases, mostly for palliative purposes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an un-precedented challenge for health systems around the world. Since radiotherapy is an essential part of the treatment in many clinical circumstances, it is necessary to evaluate which dose and fractionation scheme is the most appropriate according to the characteristics of the patient.

For the case presented, we find refractoriness to 5 lines of chemotherapy, with the persistence of the disease, in addition to HIV infection.

Taking into account the recommendations issued by The International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG) for the treatment of hematological neoplasms during the COVID-19 pandemic, we are in the palliative field of a patient with an aggressive, symptomatic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, so a hypofractionated scheme of 25 Gy in 5 Fractions was chosen, with an EQD2 for an α/β of 3 Gy = 40 Gy and an α/β of 10 Gy = 31 Gy, with the expectation of an equivalent biological effect that it would maintain the same level of tumor control, with a low risk of early and late toxicity in healthy tissues, given current radiotherapy techniques and the prescribed dose.1-13

This report describes a rare subtype of Lymphoma with activity at the rectal level, in the context of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic. For the case presented, seeking another line of chemotherapy or opting for a more divided scheme would expose the patient, due to the use of previous systemic agents and HIV infection, to a greater risk of coronavirus infection.

Despite the existence of guidelines that provide guidelines to follow for treatment in this context, individualizing the case according to the type of tumor, comorbidities, and available resources, will provide better outcomes for patients.

None.

There are no conflicts of interest.

©2022 Salvador, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.