International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8084

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 4

1University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, 2006, Australia

2GenesisCare, Mater Hospital, 25 Rocklands Rd, Crows Nest, NSW, 2065, Australia

3The Skin Hospital, 121 Crown Street, Darlinghurst, NSW, 2010, Australia

Correspondence: Prof Gerald Fogarty, GenesisCare, St Vincent’s Hospital, Victoria St, Darlinghurst, NSW, 2010, Australia, Tel +61 2 8302 5400, Fax +61 2 8302 5410

Received: September 13, 2021 | Published: October 12, 2021

Citation: Thoumi A, Fogarty GB, Paton EJ, et al. Is the contribution of Australian research to the national 2019 clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer adequate? A simple analysis. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2021;8(4):144-155. DOI: 10.15406/ijrrt.2021.08.00307

Introduction: The Australian 2002 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) treatment guidelines for non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) were updated in 2008. At this time, the lack of high-quality Australian research conducted between 2002 to 2008 was noted. The primary aim of the present study was to assess the improvement in the quantity and quality of Australian research in the 2019 keratinocyte cancer guidelines. Secondary aims included an assessment of the quantity and quality of Australian research in comparison to the guidelines provided by the other selected countries, and an evaluation of the improvements in the Australian contribution since 2008.

Method: Surgical (Sx) and radiotherapy (RT) treatment sections were interrogated. The analysis was simple. Each reference was counted as one unit. The quantity assessment was carried out by categorizing the references according to their country of origin: Australia, United Kingdom (UK), United States (US) and European Union (EU) countries, which were grouped as one country (EU) for the purpose of this study. The number of references from each country were then added up. To assess for quality, all references were ranked according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) rating scale. A quality ratio for each country was then calculated by dividing the total number of prospective trials (i.e., levels I and II) by the number of retrospective studies (level III and lower) from each country if the numbers were sufficient. To evaluate the Australian improvement since 2008, Australian references were first categorized according to their year of publication (2002 to 2017), and then allocated to one of four bins of class intervals representing time periods.

Results:

Conclusion: The contribution of Australian research to Australia’s own keratinocyte cancer guidelines is not the highest and did not improve over the period of evaluation. The same can be stated for Australia’s research contribution to the UK and US RT guidelines. Australia needs to do more high-quality research.

Keywords: keratinocyte cancers, non-melanoma skin cancer, skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, radiotherapy, surgery, treatment, research, guidelines

Keratinocyte cancers (KCs), formerly known as non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC), have one of the highest cancer incidences in Australia1 and demonstrate an increasing trend.2 As the incidence of KCs increases with age,3 alongside the co-morbidities that impact treatment, treatment can be challenging.4 KCs can cause morbidity and mortality.5 High quality research and especially randomized controlled trials (RCTs) help to guide clinicians with optimal management plans. A Parliamentary Inquiry Report6 noted that ‘Australia has earned a global reputation for its medical research, particularly in cancer.’ Australians are keen to participate in trials, especially if their results can benefit fellow sufferers.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) produces guidelines on behalf of the Australian Government to guide treatment decisions. A guideline for NMSC was produced in 20087 which updated the previously published version in 2002. The working party Chair noted at that time that ‘a disappointing feature of this review is the lack of well-designed RCTs to answer critical questions about …. treatment,’ and also that there had been ‘virtually no new major publications since this guide was last published’ with a ‘lack of definitive answers.’ This comment seemed unusual in a country with such a strong record of high-quality research, especially given that the Parliamentary Inquiry Report referred to KCs as ‘our national cancer’. The guidelines for KCs were further updated in 2019.8

The aim of the present study was first to assess the quantity and quality of the Australian research contribution to the treatment of KCs in the latest guidelines (2019). Second, to assess the Australian contribution on an international scale by analyzing the Australian content in the treatment guidelines of selected other countries, given that KC is ‘our national cancer’ and that Australia has a ‘global reputation for… medical research’. Third, this study aimed to assess if there was any improvement in Australian KC research over recent time, keeping in mind that the Chair of the 2008 guidelines stated that there was not a great improvement between 2002 and 2008. These assessments were carried out using a simple technique as described in the methods.

Our simple analysis was carried out as follows:

In the 2019 Australian guidelines,8 section 7 and its subsections (7.1 - 7.9) outline the surgical (Sx) treatment of KCs; and section 8 and its subsections (8.1 - 8.9) detail how radiotherapy (RT) can be used. Reference citations of peer reviewed journal articles were searched for in the section references.

Part 1 – Ranking of references for quality and quantity

References were identified by the reference number as it occurred in the reference citation list of the relevant subsection. The references were reviewed for quality and quantity. To analyze quantity, the references were simply added up with each one representing a single unit. To analyze quality, the references were ranked according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) rating scale for therapeutic studies as shown in Table 1. This scale ranks prospective studies as either I or II and retrospective studies as either III, IV or V. Prospective studies rank more highly than retrospective studies in terms of quality. A simple quality metric, called the quality ratio, was then established for each country by calculating the ratio of prospective to retrospective studies. This ratio was generated by putting the number of I and II studies over the number of III, IV and V studies, and expressing the result as a number.

Level of Evidence |

Quality Metrics |

I |

High-quality, multi-centered or single-centered, randomized controlled trial with adequate power; or systematic review of these studies |

II |

Lesser quality, randomized controlled trial; prospective cohort or comparative study; or systematic review of these studies |

III |

Retrospective cohort or comparative study; case-control study; or systematic review of these studies |

IV |

Case series with pre/post test; or only post test |

V |

Expert opinion developed via consensus process; case report or clinical example; or evidence based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” |

Table 1 American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) rating scale for therapeutic studies9

To rank the quality of the systematic reviews considered in this article, a quality level was assigned to each systematic review. This was achieved by first ranking all the references in the systematic review (except for other reviews referenced within the review in question), according to the ASPS rating scale. The review article was then assigned a quality rank based on the highest-ranking article within its references.

The resulting quality ranked references were then assembled according to their country of origin. Besides Australia, countries included were the United Kingdom (UK), United States (US) and those within the European Union (EU), which were considered as one under the EU for the purpose of this assessment. To determine the country of origin relevant to a reference, the geographic origin of the data used in the article was considered. Table 2 describes the references cited for Sx treatment and Table 3 for RT treatment. If a reference originated from a country that was not part of the above four countries, that reference was excluded in the numerator but kept in the denominator of the Tsb column of Tables 2 and 3.

|

Aus |

UK |

US |

EU |

|

||||||||||||||||

Sc |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

Tsb |

7 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/7 |

7.1 |

|

22 |

13 |

|

|

4 |

12 |

|

|

|

10 |

16 |

9 |

|

18 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

20/25 |

7.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1/1 |

7.3 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

7 |

|

|

|

1 |

3 |

|

|

22/27 |

7.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

10 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

4 |

3 |

|

|

11/14 |

7.5 |

|

1 |

|

|

3 |

|

16 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

2 |

13 |

5 |

|

|

15 |

|

|

15/16 |

7.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2/4 |

7.7 |

|

|

5 |

9 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

1 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

11/12 |

7.8 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

18 |

34 |

|

|

|

23 |

8 |

12 |

10 |

39 |

28 |

9 |

|

|

41/42 |

7.9 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/5 |

T |

0 |

11 |

10 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

12 |

34 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

9 |

25 |

|

|

133/153 |

Tg |

AUS = 25 |

UK = 12 |

US = 59 |

EU = 37 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Rs |

Rs = 11/14 = 0.8 |

Rs = 7/5 = 1.4 |

Rs = 14/45 = 0.31 |

Rs = 12/25 = 0.48 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Table 2 References cited in the surgical treatment subsections and numbered as they appeared in the Cancer Council Australia Keratinocyte Cancers Guideline Working Party. Clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer.8 according to quality and country of origin.

Abbreviations: AUS, Australia; US, United States; EU, European Union; UK, United Kingdom; Sc, subsection of the surgical treatment subsections of the 2019 guidelines; T, column total; Tg, grand total by country; Tsb, ratio of the total number of references from the evaluated four countries over the total number of references in the guideline subsection; Rs, quality ratio of I+II/III+IV+V

|

AUS |

UK |

US |

EU |

|

||||||||||||||||

Sc |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

Tsb |

8 |

|

|

1 |

6 |

20 |

34 |

|

17 |

|

|

|

2 |

11 |

|

|

|

7 |

5 |

|

|

28/34 |

8.1 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

12 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

9 |

|

4 |

|

|

17/22 |

8.2 |

|

|

26 |

60 |

39 |

|

|

27 |

|

|

|

56 |

6 |

|

40 |

30 |

4 |

3 |

|

|

48/66 |

8.3 |

|

30 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

45 |

46 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

39/47 |

8.4 |

|

45 |

3 |

|

7 |

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

49 |

4

|

29 |

28 |

|

12 |

|

|

|

51/61 |

8.5 |

5 |

|

|

|

15 |

13 |

|

|

|

19 |

6 |

4 |

20 |

12 |

|

8 |

3 |

9 |

|

|

14/20 |

8.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

2/2 |

8.7 |

|

|

4 |

|

2 |

|

14 |

|

|

|

31 |

3 |

1

|

|

7 |

|

|

11 |

15 |

5 |

31/35 |

8.8 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

4 |

|

7 |

8 |

|

|

5/8 |

8.9 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

¾ |

T |

1 |

2 |

37 |

3 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

14 |

76 |

6 |

9 |

4 |

12 |

42 |

2 |

2 |

238/299 |

Tg |

AUS = 53 |

UK = 16 |

US = 107 |

EU = 62 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Rs |

Rs = 3/50 = 0.06 |

Rs = 4/12 = 0.3 |

Rs = 16/91 = 0.18 |

Rs = 16/46 = 0.34 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Table 3 References cited in the RT subsections and numbered as they appeared in the Cancer Council Australia Keratinocyte Cancers Guideline Working Party. Clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer8 according to quality and country of origin.

Abbreviations: AUS, Australia; US, United States; EU, European Union; UK, United Kingdom; Sc, subsection of the Radiotherapy treatment subsections of the 2019 guidelines; T, column total; Tg, grand total by country; Tsb, ratio of the total number of references from the evaluated four countries over the total number of references in the guideline subsection; Rs, quality ratio of I+II/III+IV+V

Part 2 – Ranking of Australian references in the national multidisciplinary guidelines of other countries

To illustrate how Australia’s research efforts for Sx and RT are cited as treatment options in the guidelines of the selected countries, the same methodology was applied. References for the national multidisciplinary guidelines of the UK10 are shown in Table 4. References for the national American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) clinical practice guidelines11 are shown in Table 5.

|

AUS |

UK |

US |

EU |

|

||||||||||||||||

Sc |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

|

Ref no |

|

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

16 19 |

|

|

10 |

18 |

9 |

|

|

|

Tg |

AUS = 3 |

UK = 1 |

US = 2 |

EU = 5 |

Tr =11/19 |

||||||||||||||||

Rs |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Rs = 2/3 = 0.67 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Table 4 References cited in the United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines including diagnosis, surgery, radiotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and topical drugs arranged according to quality and country of origin.10

Abbreviations: AUS, Australia; US, United States; EU, European Union; UK, United Kingdom; Ref no, reference number as it appears in the guidelines reference section; Tg, grand total by country; Rs, quality ratio of I+II/III+IV+V; Tr, total number of references for surgery and radiotherapy modalities of treatment over the total number of references cited in the guidelines that included all modalities of treatment and from all countries.

|

AUS |

UK |

US |

EU |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

|

Refno |

64

|

114 |

29 |

|

|

|

|

104 |

|

|

84 |

83 |

5

|

|

87 |

3 |

12 |

9 |

11 |

32 |

|

T |

1 |

1 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

36 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

28 |

1 |

1 |

|

Tg |

AUS = 20 |

UK = 1 |

US = 44 |

EU = 36 |

Tr=101/129 |

||||||||||||||||

Rs |

Rs = 2/18 = 0.11 |

Rs = NA |

Rs = 7/37 = 0.19 |

Rs = 6/30 = 0.2 |

|

||||||||||||||||

Table 5 References cited in the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) clinical practice guidelines11 according to quality and country of origin.11

Abbreviations: AUS, Australia; US, United States; EU, European Union; UK, United Kingdom; Ref no, reference number as it appears in the guidelines reference section; T, column total; Tg, grand total by country; Rs, quality ratio of I+II/III+IV+V; Tr, total number of references for surgery and radiotherapy modalities of treatment out of the total number of references cited in the guidelines that included all modalities of treatment and from all countries.

Part 3 – Ranking of Australian refences for quality and quantity over time

An analysis to compare the references from Australia over time to the changing incidence of KCs over time was then attempted using graphs.

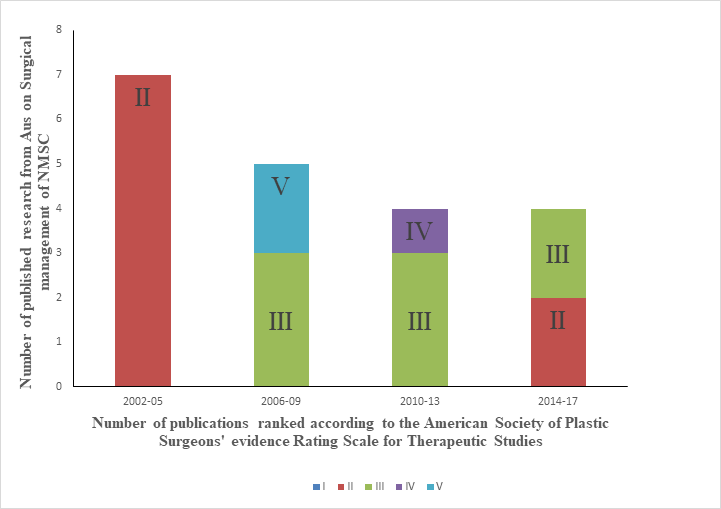

To evaluate the development of research over the evaluated period of time, references were graded according to the year of publication and were categorized into four ‘bins’ with each bin representing a 4-year period without any overlap. The four bins and their intervals were: 2002-2005, 2006-2009, 2010-2013 and 2014-2017. The number of references was represented as stacked column graphs. This enabled the reference quality to be displayed as different parts of the column depending on the quality allocated, as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Part 1 – Ranking of references for quality and quantity

A total of 133 references on the surgical treatment of KCs were found in the Australian guidelines8 as shown in Table 2. The number of Australian studies cited in the guidelines8 was 25, which is less than those from the US (58) and EU (37), but better than the UK (12). The Australian and UK contributions had, however, a higher proportion of prospective studies with quality ratios of 0.8 and 1.4, respectively. Those from the US and EU were more retrospective in nature with quality ratios of 0.31 and 0.48, respectively.

A total of 238 references from the four countries pertaining to the treatment of KCs using RT were found in the Australian guidelines.8 The number of Australian studies was 53, which was less than the US (107) and EU (62) but better than the UK (16). The Australian and UK contributions had a lower proportion of prospective studies with quality ratios of 0.06 and 0.3, respectively, as compared with those from the US and EU where the quality ratios were 0.18 and 0.34, respectively.

Part 2 – Ranking of Australian references in national guidelines of other countries

Table 4 highlights the inclusion of only 11 publications from the four countries on the RT treatment of KCs in the UK guidelines.10 Only three Australian studies contributed to the total number of references, which was less than those from the EU (5) but more than the US (2) and UK (1). Meaningful quality ratios could not be determined except for the EU at 0.67.

As illustrated in Table 5, there were a total of 101 references from the four countries relating to the treatment of KCs using RT in the ASTRO guidelines.11 The number of Australian studies referenced in these guidelines was 20, which was less than the US (44) and EU (36), but better than the UK (1). The Australian contribution also had a lower proportion of prospective studies with a quality ratio of 0.11 compared with those from the US and EU with quality ratios of 0.19 and 0.2, respectively. A meaningful quality ratio could not be determined for the UK.

Part 3 – Ranking of Australian references for quality and quantity over the evaluated period of time

Figure 1: References over time for surgical treatments using a stacked column graph. The vertical axis shows the number of references. The columns show the total number of references divided into the quality stacks according to their rank on the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' evidence Rating Scale for Therapeutic Studies. The references were then allocated according to their year of publication (2002 - 2017), in four-year intervals. Legend: I, II, III, IV and V are the levels of evidence according to American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) rating scale for therapeutic studies.9

Figure 1 illustrates that the quantity and quality of Australian research on surgical treatment is decreasing overall.

Abbreviations: Aus, Australia; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer

Figure 2: References over time for radiotherapy treatments using a stacked column graph. The vertical axis shows the number of references. The columns show the total number of references divided into the quality stacks according to their rank on the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' evidence Rating Scale for Therapeutic Studies. The references were then allocated according to year of publication (2002 -2017), in four-year intervals. Legend: I, II, III, IV and V are the levels of evidence according to American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) rating scale for therapeutic studies.9

This study set out to achieve three aims.

The first was to assess the quantity and quality of the contribution of Australian research to the treatment of KCs in the latest Australian guidelines.8 For the question of overall quantity, Australian research contributed less information than the US and EU, but more than the UK. For quality, the Australian and UK surgical contributions had a higher proportion of prospective studies which increased their quality ratios compared to the US and EU; however, for RT, the Australian and UK contributions had fewer prospective studies compared to the US and EU, resulting in decreased quality as summarized in Table 6.

|

Aus |

UK |

US |

EU |

Total |

Section 7 |

25 (19%) |

12 |

58 |

37 |

132 |

Quality Ratio |

0.8 |

1.4 |

0.31 |

0.48 |

1 |

Section 8 |

53 (22.3%) |

16 |

107 |

62 |

238 |

Quality Ratio |

0.06 |

0.3 |

0.18 |

0.34 |

1 |

Table 6 Reference citations and quality ratios in the 2019 Guidelines for Sx and RT treatment from selected countries

Abbreviations: Aus, Australia; US, United States; EU, European Union; UK, United Kingdom

The second aim was to assess the Australian research contribution to the guidelines of selected countries. We observed that Australian research does contribute to the US and UK guidelines; however, the US preferentially self-cites and cites EU research over Australian research.

Given that the 2008 guidelines were criticized for their lack of new major publications and well-designed randomized controlled trials, the third aim of this study was to evaluate the recent Australian keratinocyte cancer research for an improvement. Considering the increasing incidence of KCs, local research would be expected to increase; however, Figure 1 shows that Australian surgical research had some early quality before 2005 but that the overall quality and quantity has declined since then. Furthermore, there were no Australian studies from 2002-2005 on the use of RT to treat KC, which is an even worse scenario. Fortunately, some studies have now been published but the quality remains inferior.

The reasons behind this lack of Australian research into what the Australian Government deems to be “our national cancer” is beyond the scope of this study; however, the following suggestions warrant consideration. In Australia, due to sheer numbers, KCs are not reported. This could give the impression that the Government is not interested, or that skin cancer is not given appropriate attention. Another reason could be that in acute hospital settings, more and more cancers are looked after by multidisciplinary teams. The resulting inter-specialty communication leads naturally to prospective trials that create the evidence to guide treatment. Skin, however, is traditionally looked after in a community setting rather than in an acute hospital, so skin care professionals may be more isolated or devoid of the knowledge or opportunity to participate in trials. Finally, it may be that KCs lack the organized patient advocacy groups that can help to drive trial initiation, as is seen with other cancers.

In summary, those who care for skin cancer in Australia need to appreciate that the world needs high quality research when it comes to KC. Australia contributes significantly to the international body of research in other cancers, and we should be leading the way for “our national cancer”. Hopefully, by the time the next KC guideline revisions are due, there will be more Australian high-quality clinical evidence to guide best practice.

This study assessed the contribution of Australian research to the 2019 Australian clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer8 and to the skin cancer guidelines of other selected countries. Using a simple analysis, we showed that the quantity and quality of Australian research on the use of surgery and radiation therapy to treat keratinocyte cancers in the latest Australian guidelines is low, and lower even than the contribution of selected other countries. The Australian research contribution to the national guidelines of selected other countries is also low, and the rate and quality of Australian based research is not improving with time. This is particularly concerning as the incidence of keratinocyte cancers in Australia is increasing. Given that keratinocyte cancer is considered Australia’s national cancer, the Australian skin cancer community should use its expertise to drive skin cancer research as a matter of urgency.

The authors wish to thank Cancer Council Australia for their ongoing support and for funding the medical writer’s contribution. They also wish to thank Aileen Eiszele of A&L Medical Communications for editing the manuscript and overseeing the journal submission process.

Cancer Council Australia Keratinocyte Cancers Guideline Working Party. Clinical practice guidelines for keratinocyte cancer. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia. 2019.

Likhacheva A, Awan M, Barker CA, et al. Definitive and postoperative radiation therapy for basal and squamous cell cancers of the skin: An ASTRO clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020;10(1):8‒20.

©2021 Thoumi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.