International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

1Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, México

2Estudiante de Doctorado en Genética y Biología Molecular, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Campiñas, Brasil

Correspondence: Víctor Hugo Díaz Fuentes, Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. México, Kilómetro 18 carretera Tapachula-Cacahoatán, Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, México, Tel 8000882222 ext. 86410

Received: December 30, 2021 | Published: January 13, 2022

Citation: Fuentes VHD, Hernández BGD. Technical and economic validation of the fruit thinning practice in commercial mangosteen plantations in the Soconusco region, Chiapas. Mexico. Int J Hydro. 2022;6(1):1-5. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2022.06.00295

The objective of the work was to validate the technical and economic efficiency of thinning to increase the size and weight of mangosteen fruits. The validation was carried out in 2021, in two commercial plantations of mangosteen 10 and 13 years old located in the municipalities of Tapachula, and Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, Mexico, respectively. The factors in study are thinning with two levels: thinned 30% and unthinned (control) and three initial fruiting ranges (RFI): 80-120 fruits; 121 to 160 fruits and> 160 fruits. By combining the study factors, 6 treatments were formed: RFI 80-120-thinned; RFI 121-160-thinned; RFI >160-thinned; RFI 80-120-unthinned RFI 121-160-unthinned and RFI >160-unthinned. A completely random design with four repetitions was used. The experimental unit consisted of a tree, with a total of 24 trees in 0.14 ha in each plantation under study. The study variables were yield/tree; fruit weight and fruits/tree. The economic comparison between treatments was made and the return to capital (cost-benefit ratio) of them was calculated. In both plantations evaluated, a significant statistical difference was found in fruits/tree, fruit weight, yield/tree and yield/ha. The highest average weight of the fruits (> 76 g in accordance with the requirements of international markets.) and percentage of them, is obtained in trees thinned. The highest cost-benefit ratio (4.5 in Tuxtla Chico plantation and 2.3 in Tapachula plantation), was obtained in RFI >160 thinned treatment.

Keywords: mangosteen, increased, weight, fruits, standards, quality

Globalization and expansion of international markets have made possible a greater knowledge and access to the mangosteen Garcinia mangostana L., which until just a few years ago was an unknown fruit in many countries. In recent years, the combination of its exquisite flavor, unique appearance, and the discovery of its high content of natural antioxidants and other nutraceutical and medicinal properties, have stimulated an increase in its demand in international and national markets.1 It is currently cultivated on a commercial scale in India, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines and to a lesser extent in Sri Lanka, Australia, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil and Colombia.2,3 Its growing international demand is satisfied mainly by Thailand, a leading country in the production and export of mangosteen, whose production in 2017 was 530,000 MT, (75% of world production) of which it exported 205,000 MT which means an increase of 44% in exports compared to 2016. Other major mangosteen exporters include Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and India6. Globally, China is the main importer.4 The value of mangosteen exports to China was 158, 238 and 149 million dollars in 2014, 2015 and 2016 respectively.5 Thailand is the main exporter of mangosteen to China. In 2019, Thai mangosteen exports to China reached a total volume greater than 300,000 MT. With an average unit export value of USD 1,270 per tonne (for shipments from Thailand to China during 2019), mangosteen is among the most valuable tropical fruits available on world markets.6

In this context of growing demand and attractive prices for mangosteen, emerging Latin American countries in the cultivation of mangosteen such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Brazil and Colombia, have found an opportunity for agribusiness in its production and export. Even though the export volumes of these countries are still small compared to the exports of Asian countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, in Latin American countries there is a trend of a constant increase in exported volumes. In the case of Mexico, whose planted area is approximately 720 ha,7 during the 2015-2019 period, Mexican mangosteen exports increased by 22.6%, going from 338.2 t in 2015 to 414.7 T in 2019, with an average annual growth of 5.6% in exports8 (Although it is highly probable that these estimates of the exported volume do not correspond only to national production, since Mexican traders acquire mangosteen mainly from Guatemala or other countries in the region, which is exported to the USA as a Mexican product. The USA is the main destination for exports of mangosteen produced in Latin America, mainly Los Angeles and New York, which have a high migrant population (which constitute the so-called "nostalgia markets"), mainly of Asian origin.

Despite its high potential as an export product, the low quality of a high percentage of the fruits produced in Mexico and other Latin American countries. constitutes one of the main problems faced by producers and marketers for the export of mangosteen. The quality of the mangosteen fruit is evaluated according to the Codex Standard Stan 204-19979 (FAO, 2005). The standard refers to characteristics of the size of the fruit (weight and diameter of the equatorial section), and its physical state (whole, with intact calyx and peduncle, without damage by pests, diseases or latex exposure in the pericarp).10,11 For size (weight and diameter), the standard establishes the classification indicated in Table 1.

|

Size code |

Weight (g) |

Diameter (mm) |

|

A |

30 - 50 |

38 - 45 |

|

B |

51 - 75 |

46 – 52 |

|

C |

76 - 100 |

53 - 58 |

|

D |

101 - 125 |

59 - 62 |

|

And |

> 125 |

> 62,4 |

Table 1 Classification of mangosteen fruits by size according to Codex Standard Stan 204-1997. (FAO, 2005)

Sizes C, D and E (Table 1) are considered suitable for export. However, in Mexico, a high percentage of the harvested fruits corresponds to fruits weighing less than 70 g that do not fit the size requirements for export purposes. In a study carried on the productive behavior of the mangosteen in the Soconusco Region, Chiapas, it was found that during the first four harvests (corresponding to the period 2015 - 2018) between 52 and 92% of the harvested fruits registered a weight of less than 80 g3. In this context, thinning is considered a viable alternative to increase the size and weight of fruits and to reduce the productive alternation in mangosteen.

Thinning is a practice that consists of the manual, mechanical or chemical removal of the fruits to regulate the crop load (number of fruits) in trees. With the opportune thinning, the competition for carbohydrates between the fruits that remain on the tree is reduced, which have a greater amount of reserves for their development, promoting cell division and elongation, which translates into greater growth of the fruits with a greater accumulation of sugars.12 Thinning allows the production of fruits with a higher quality in terms of weight, size, color, internal quality, and the alternation of production is controlled by promoting greater flowering in the following year.13,14 In an experiment was carried out to determine the response of mangosteen trees with different initial fruiting conditions, to different thinning intensities to increase the weight and size of the fruit according to the requirements of international markets, highest value of production in trees with initial fruiting of 40 to more than 120 fruits, before thinning, is obtained with the thinning of 30% of the fruits.15

According to the National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP) policies, once the technology has been generated under experimental conditions, and before its massive dissemination, it must be validated, under farmers conditions.16 Accordingly, the objective of this work was to determine the technical efficiency and profitability of the thinning practice to increase the size and weight of mangosteen fruits in commercial plantations of the Soconusco region, Chiapas, Mexico, generated by INIFAP.

The validation of the technology on fruit thinning in mangosteen was carried out during the year 2021 in two commercial mangosteen plantations of 13 and 10 years old established in the municipalities of Tuxtla Chico and Tapachula, Chis., respectively.

In Tapachula the plantation under study is located at 71 m altitude. The predominant climate is the warm humid with rains in Summer. The average annual temperature in the area is 27.5 °C, with a minimum average of 21 °C and maximum annual average of 34.1 °C. The average annual rainfall is 2065 mm. The plantation was established in 2011, at distances of 8 x 8 m between lines and plants (156 trees ha-1).

In Tuxtla Chico the plantation under study is located at 173 m altitude. The predominant climate is the warm humid with rains in Summer. The average annual temperature in the area is 25.9 °C, with a minimum average of 19.5 °C and maximum annual average of 32.4 °C. The average annual rainfall is 3831 mm. The plantation was established in 2008, at distances of 8 x 8 m between lines and plants (156 trees ha-1).

A thinning intensity of 30% of the total fruits of trees with three ranges initial fruiting ranges (RFI) was applied. RFIs similar to those used in the mangosteen thinning technology generator experiment15 : a) RFI 80-120 fruits; b). RFI 121 to 160 fruits and, c). RFI> 160 fruits as well as a unthinned treatments (control) in trees with the three aforementioned RFIs. By combining the study factors and their respective variants, 6 treatments were formed (RFI 80-120-thinned; RFI 121-160-thinned; RFI >160-thinned; RFI 80-120-unthinned; RFI 121-160 - unthinned and RFI >160-unthinned in a completely randomized experimental design with four repetitions. The experimental unit consisted of a tree, with a total of 24 trees in 0.14 ha in each plantation under study. Fruit thinning was carried out manually 45 days after the start of flowering, in the initial stage of fruit development. Small fruits, weighing less than 20 g, and those that are grouped on the same branch, were mainly eliminated, leaving only one fruit per branch. The study variables were yield/tree; fruit weight and fruits/ tree, quantified as the accumulation of mature fruits collected during the harvest period. The harvest was carried out twice a week during the period from April 29 to June 06 in Tapachula plantation and May 13 to June 13 in Tuxtla Chico plantation.

The individual weight of each fruit harvested per treatment was recorded with a precision digital electronic scale in centigrams. The yield per tree was calculated with the accumulated value of the individual fruit weights. To calculate the yield per hectare, the yield per tree obtained in each treatment under evaluation was multiplied by 156, which corresponds to the number of trees/ha (population density) existing in the study plantations. The data were analyzed using the standard procedure of analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple comparison test of means (P≤0.05) with the SAS computer program (SAS Institute, 1999).

The harvested fruits of each treatment under evaluation were grouped into two ranges according to their weight and commercial category: a). Fruits with weight ≥ 76 g (with export quality), with an average selling price of 6.06 USA dollars/kg y, b). Fruits with weight < 76 g, with an average selling price of US$3.03/kg during the harvest period. To obtain the return to capital or benefit-cost ratio, the gross profit (yield/ha multiply by sale price) was divided by the production cost of the treatment.

Tuxtla Chico plantation

In the plantation of Tuxtla Chico, analysis of variance detected a significant statistical difference (p≤ 0.05) in the variables the number of fruits/tree, fruit weight, yield/tree and yield/ha (Table 2). In treatments with similar RFI, the highest number of fruits per tree was recorded in unthinned treatments. In this variable, the mean comparison test (p≤0.05) showed that RFI treatment >161-unthinned, is significantly higher than the rest of the treatments under evaluation. However, this treatment recorded the lowest average fruit weight (68.5 g). On the contrary, in RFI 80-120-thinned treatment, with lowest number of fruits/tree, the highest average fruit weights (81.9 g) were recorded, which corroborates that as in other fruit trees, the number of fruits per tree had a significant influence on the fruit weight,17,18 Greater fruiting results in lower weight of fruits and vice versa.

|

Treatment |

Fruits/tree |

Weight fruit (g) |

Yield tree (k) |

Yield ha-1 (t) |

|

Unthinned--RFI >161 |

486 a |

68.5 c |

32.6 ab |

5.1 ab |

|

Thinned-RFI > 161 |

476 ab |

78.6 abc |

36.9 a |

5.8 a |

|

Thinned-RFI 121-161 |

375 abc |

81.6 ab |

29.8 ab |

4.7 ab |

|

Unthinned-RFI 121-161 |

359 abc |

70.3 abc |

23.8 b |

3.7 b |

|

Unthinned-RFI 80-120 |

291 c |

72.1 abc |

20.3 b |

3.2 b |

|

Thinned-RFI 80-120 |

257 c |

81.9 a |

21.2 b |

3.3 b |

|

Average |

374 |

75.5 |

27.4 |

4.3 |

|

C. V. (%) |

28 |

10 |

29 |

29 |

|

DMS |

152 |

12.6 |

12.7 |

1.9 |

Table 2 Average values of fruits/tree, fruit weight, yield/tree and yield/ha in thinned and unthinned treatments in trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 13 years old mangosteen plantation. Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas

Treatments with the same letters in the row and column, are statistically similar according to the DMS test, 0.05.

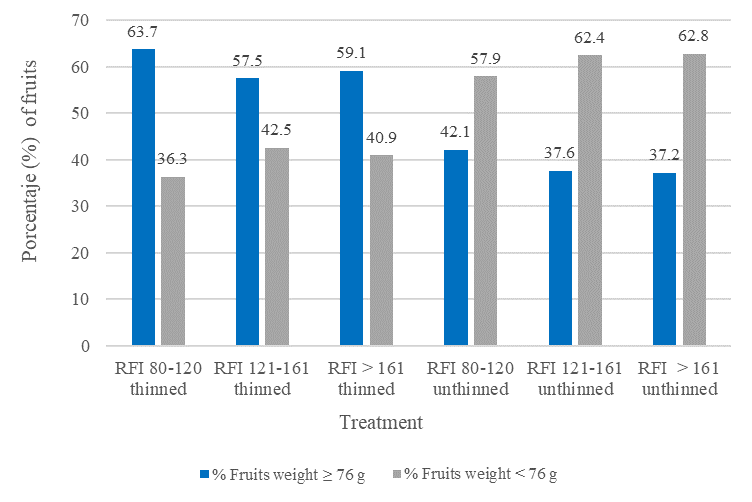

The yield per tree and per hectare obtained in RFI >161 thinned treatments, is statistically higher (p≤ 0.05) than the rest of the treatments, in a range of 11 to 46%. This is indicative that, in the case of adult mangosteen trees, with initial fruiting greater than 160 fruits (15-20 days after the starting of fruit development), moderate thinning (such as that applied in this study), increases the yield per tree and consequently per hectare from the same year in which this practice is carried out. This differs from what it was reported by other authors who point out that in somecases, the yields of thinned trees are equal to or less than those of trees unthinned.19 For example, in pecan nuts, fruit thinning of 44%, decreases total yield per tree from 88 to 53 lb/tree for the current year, unless this is compensated by the higher commercial value of the harvested fruits and stabilization of the yield in subsequent harvests.20 In similar RFI treatments, the yields per tree and per hectare/tree in thinned treatments are higher than unthinned treatments. The greater increase in yields per tree and per hectare recorded in thinned treatments is a consequence of a greater percentage of fruits with greater weight (> 76 g) compared to unthinned treatments, where the percentages of fruits with a weight of less than 76 g predominate (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Percentage of fruits, weighing ≥ and > 76 g, in thinned and unthinned treatments in trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 13 years old mangosteen plantation. Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas.

Tapachula plantation

In all the study variables, in the Tapachula plantation, values lower than those corresponding to the Tuxtla Chico plantation were recorded (Table 3). This is attributable to the age difference of both plantations. As in the Tuxtla Chico plantation, in the Tapachula plantation, the analysis of variance detected a significant statistical difference (p≤ 0.05) in fruits/tree, fruit weight, yield/tree and yield/ha.

|

Treatment |

Fruits/tree |

Weight fruit (g) |

Yield tree (k) |

Yield ha-1 (t) |

|

Unthinned--RFI >161 |

284 a |

65.8 bc |

17.5 a |

2.73 a |

|

Thinned-RFI > 161 |

245 ab |

71.7 abc |

16.3 ab |

2.54 ab |

|

Unthinned-RFI 121-161 |

236 ab |

65.6 c |

15.1 abc |

236 abc |

|

Thinned-RFI 121-161 |

208 ab |

74.9 ab |

15.2 abc |

2.37 abc |

|

Unthinned-RFI 80-120 |

191 ab |

67.6 abc |

12.5 abc |

1.95 abc |

|

Thinned-RFI 80-120 |

140 b |

75.3 a |

10.5 c |

1.64 c |

|

Average |

217 |

70.1 |

14.5 |

2.73 |

|

C. V. (%) |

29 |

7 |

22 |

22 |

|

DMS |

111 |

9.1 |

5.7 |

0.9 |

Table 3 Average values of fruits/tree, fruit weight, yield/tree and yield/ha in thinned and unthinned treatments in trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 8 years old mangosteen plantation. Tapachula, Chiapas

Treatmens with the same letters in the row and column, are statistically similar according to the DMS test, 0.05.

As it can be seen in Table 3, in treatments with similar RFI, the highest number of fruits per tree was recorded in unthinned treatments. Similar to the trend observed in the Tuxtla Chico plantation, in the Tapachula plantation the mean comparison test (p≤0.05) showed that RFI >161 unthinned, is significantly higher than the rest of the treatments under evaluation in the number of fruits/tree, although with one of the lowest average weights of fruits (65.8 g). On the contrary, in the RFI 80-120 thinned treatment, where the lowest number of fruits/tree was recorded, the highest average fruit weights (75.3 g) were recorded. RFI > 161-unthinned treatment is statistically superior (p≤ 0.05) to the rest of the treatments in yield per tree and per hectare. At the mean level, the average yields of both variables recorded in this treatment are 7% higher than the thinned treatment and similar RFI (RFI > 161 thinned). Contrary to what was observed in the Tuxtla Chico plantation, in the Tapachula plantation, in unthinned treatments there is a trend of higher yields per tree and per hectare in unthinned treatments, in comparison to thinned treatments and similar RFI. Even though with thinned treatments fruits with higher weight predominate (> 76 g), with unthinned treatments the number of fruits/tree is higher, which compensates for the yield (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Percentage (%) of fruits, weighing ≥ and < 76 g, in thinned and unthinned treatments in trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 8 years old mangosteen plantation. Tapachula, Chiapas.

The results recorded in the Tapachula plantation suggest that in trees that begin their productive stage and consequently, their initial fruiting is still incipient, thinning has a smaller effect on yield at the tree and production unit level. The results obtained in both plantations also confirm for mangosteen, the strong interrelation between fruiting and fruit weight (the higher the fruiting-lower the weight and vice versa), reported by other authors already mentioned.17,18

Economic analysis

In Tapachula plantation, lower values of the cost-benefit ratio of each treatment were determined in comparison to Tuxtla Chico plantation. As it was mentioned above this is a consequence of the difference in age, and consequently in the yield in both plantations.

In Tuxtla Chico plantation, in treatments with similar RFI, economic analysis determined a greater cost-benefit ratio in thinned treatments. the highest cost-benefit ratio (4.5) was recorded in RFI > 161-thinned treatment, which means that for every dollar invested in the application of this treatment, that dollar is recovered and 3.5 dollars more are obtained (Table 4).

|

Treatment |

Yield by weight class |

Gross profit/ha (US dollars) |

Gross profit/ha (US dollars) |

Production cost |

Cost/Benefit ratio |

|||

|

Yield (t/ha) |

Fruits ≥ 76 g (t/ha) |

Fruits < 76 g (t/ha) |

Fruits ≥ 76 g |

Fruits <76 g |

(US dollars) |

|||

|

RFI > 161 thinned |

5.8 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

20,775 |

7,188 |

27,963 |

6201 |

4.5 |

|

RFI 121-161 thinned |

4.7 |

2.7 |

2 |

16,379 |

6,053 |

22,432 |

6186 |

3.6 |

|

RFI > 161 unthinned |

5.1 |

1.9 |

3.2 |

11,498 |

9,705 |

21,204 |

6037 |

3.5 |

|

RFI 80-120 thinned |

3.3 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

12,740 |

3,630 |

16,370 |

6176 |

2.6 |

|

RFI 121-161 unthinned |

3.7 |

1.4 |

2.3 |

8,432 |

6,996 |

15,428 |

6037 |

2.5 |

|

RFI 80-120 unthinned |

3.2 |

1.3 |

1.9 |

8,165 |

5,615 |

13,779 |

6037 |

2.2 |

Table 4 Cost-benefit ratio in thinned and unthinned treatments in trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 13 years old mangosteen plantation. Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas

Sale Price by weight fruits class: Fruits ≥ 76 g: 6.06 US Dollars; Fruits < 76 g: 3.03 US dollars

In Tapachula plantation, the cost-benefit ratio obtained in RFI > 161 thinned, RFI > 161 unthinned and RFI 121-161 thinned treatments is similar. However, it is noteworthy that in treatments RFI > 161 thinned and RFI 121-161 thinned), yields/ha are lower than RFI>161 unthinned treatment (Table 5).

| Treatment | Yield (t/ha) | Yield by weight class | Gross profit/ha (US dollars) | Gross profit/ha (US dollars) | Production cost (US dollars) | Cost/Benefit ratio | ||

| Fruits ≥ 76 g (t/ha) | Fruits < 76 g (t/ha) | Fruits ≥ 76 g | Fruits < 76 g | |||||

| RFI > 161 thinned | 2.54 | 1.34 | 1.2 | 8,096 | 3,648 | 11,744 | 5013 | 2.3 |

| RFI > 161 unthinned | 2.72 | 0.9 | 1.82 | 5,472 | 5,505 | 10,978 | 4864 | 2.2 |

| RFI 121-161 thinned | 2.37 | 1.26 | 1.11 | 7,655 | 3,354 | 11,009 | 5008 | 2.1 |

| RFI 121-161 unthinned | 2.35 | 0.73 | 1.62 | 4,400 | 4,920 | 9,321 | 4864 | 1.9 |

| RFI 80-120 unthinned | 1.95 | 0.71 | 1.24 | 4,325 | 3,746 | 8,071 | 4864 | 1.6 |

| RFI 80-120 thinned | 1.63 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 5,936.60 | 1,971 | 7,907 | 5003 | 1.5 |

Table 5 Cost-benefit ratio in six treatments with thinning and without thinning and trees with three initial fruiting ranges (RFI) in 8 years old mangosteen plantation. Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico

The value of the cost benefit ratio of thinning and unthinned treatments in Tuxtla Chico plantation, and thinned in Tapachula plantation are higher than those reported for mangosteen plantations of Chanthaburi Province in Thailand where BC ratio of 1.79 is reported.21 In treatments unthinned in Tapachula plantation, the results are coincident with the BC ratio said report. However, the cost-benefit ratio calculated in both plantations evaluated in the study are similar to that refueled for plantations of 8 and 13 years of age in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia where cost benefit ratios of 1.93 and 4.13 respectively were obtained.22

Although the highest number of fruits per tree was recorded in the treatments without thinning, the highest average weight of the fruits (in accordance with the requirements of international markets.) and percentage of them, is obtained in trees with thinning.

In adult mangosteen trees (case of Tuxtla Chico plantation), by applying the RFI >160 thinned treatment, the yield per tree increased, and consequently per hectare, from the same year in which this practice was carried out. With this treatment, cost-benefit ratio of 4.5 obtained, was 20% higher than the 3.6 obtained in treatment with similar RFI without thinning (RFI >160 unthinned).

In trees that are just beginning their productive stage (the case of the Tapachula plantation), and consequently their initial fruiting is still incipient, thinning has a smaller effect on yield. However, as in the Tapachula plantation, by applying the RFI treatment >160 thinned, the highest value in the cost benefit ratio (2.3) is obtained. This suggests, as it has been reported in other adult fruit trees, the future increase in fruiting in relation to the age of the tree and the stabilization of the yield in subsequent harvests, thus increasing the cost-benefit ratio with RFI >160 thinned treatment.

The results of the economic analysis in both plantations corroborate the effect of thinning for the production of fruits with greater weight and value in the market, and consequently, the higher productivity of cultivation of mangosteen in Mexico.

To Engineer Romeo Esponda Gálvez and Engineer Abel Méndez Ávila, owners of the mangosteen plantations of Tuxtla Chico and Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, respectively, for all the facilities provided to carry out field work in their plantations, and provide updated information on sale prices of mangosteen in Mexico, used for the economic analysis of the study.

The authors declare no conflict of interest exists.

©2022 Fuentes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.