International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 3

1Docente permanente da 13ª Unidade Regional de Ensino (URE), Secretaria de Estado de Educação do Pará – SEDUC, Belém, (PA), Brasil

2Docente permanente do Departamento de Ciências Naturais e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais (PPGCA), Universidade do Estado do Pará – UEPA, Belém (PA), Brasil

3Docente permanente do Departamento de Ciências Naturais (DCN), Universidade do Estado do Pará – UEPA, Belém (PA), Brasil

Correspondence: João Raimundo Alves Marques, Docente permanente da 13ª Unidade Regional de Ensino (URE), Secretaria de Estado de Educação do Pará – SEDUC, Belém, (PA), Brasil, Tel (91) 980385980

Received: May 18, 2021 | Published: June 14, 2021

Citation: Marques JRA, Gutjahr ALN, Braga CES. Socio-economic and environmental characterization of the residents of igarapé santa cruz, breves, arquipelago de marajó, pará, Brazil. Int J Hydro. 2021;5(3):115-123. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2021.05.00273

The socioeconomic and environmental problems resulting from disordered occupation on the outskirts of cities propitiate dire living conditions. In this scenario, it is important to develop studies that describe people's living conditions and the degree of environmental degradation to which they are subject. Thus, this study aims to diagnose the socioeconomic and environmental aspects of the residents living on the bank of the Santa Cruz stream that is located in the peripheral area of the municipality of Breves, Pará. The study is a quantitative and descriptive research in which the questionnaire was used to collect information on the socioeconomic and environmental profile of 257 families living in the Santa Cruz stream. The results showed that the majority of the inhabitants (57.30%) have incomplete Elementary School; 72.36% receive less than 1 minimum wage, the main occupation is informal work, 77.82% live in houses built of wood, 68.09% of households use the water from the stream for domestic use, 48.64% of households have a sanitary destination for dry cesspits and 13, 62% the sanitary destination is direct in the stream. In this context, residents live in a favorable conditions to social exclusion, unhealthiness and diseases, due to the poor socioeconomic, environmental and infrastructure conditions. Therefore, that the diagnosis of living conditions of the resident population of the stream, experience conditions of misery and abandonment.

Keywords: socioeconomics, environment, disorganized occupation, Amazon

The socioeconomic and environmental problems arising from disorderly occupation in the outskirts of cities are possibly linked to the reality of poverty and lack of access to land.1 In this sense, the economically excluded population ends up composing poverty belts around large urban centers, settling in areas called invaded and often in default of the laws and norms established for building and land use, or in inappropriate places or prohibited to use and without any infrastructure to meet quality of life expectations.2 Therefore, the poorest groups in society are considered more vulnerable to violence, unhealthy conditions, diseases and other social problems, Although it is visible that technological advances are taking place at an accelerated pace, within the current economic process, this rapid development does not benefit all people. In the Amazon, a large part of the population still lacks basic services for a better quality of life, with insufficient housing, food and services.3 In this context, the provision of public infrastructure and sanitation services in many rural areas and urban outskirts is still precarious or non-existent, imposing on the inhabitants unhealthy conditions that cause diseases.4,5

Poverty exists in both developed and developing countries.6 However, in countries like Brazil, socioeconomic and environmental inequalities are visible, highlighting the states in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, which have the lowest Human Development Index – HDI (IBGE, 2010).7 Thus, various areas of knowledge, such as the social sciences, propose through research possibilities to minimize poverty and social exclusion, arising from factors such as poor income distribution, low education and inefficiency in integrated public policies that address communities and municipalities in less favored regions.8,9 The municipalities of the Archipelago of Marajó show the lowest quality of life for the population in the state of Pará. These municipalities have precarious or poor sanitation infrastructure, unhealthy conditions, low education, which place the population in conditions of socioeconomic vulnerability and in the lowest HDI in the northern region.10

In the urbanization scenario in the Marajoara region, the municipality of Breves-PA stands out, where the disorderly occupation on the banks of the Santa Cruz stream is evident, whose consequences are harmful to health and the environment. In this locality, the inhabitants live in conditions conducive to unemployment, social exclusion, unhealthy conditions and illnesses. In this context, any study that addresses the living conditions, the degree of environmental degradation and the unsustainability of populations in peripheral areas becomes important. Such studies produce diagnoses that can support the implementation of public policies aimed at basic sanitation and income-generating activities, which contribute to a better quality of life for such populations. Thus, this study aims to diagnose the socioeconomic and environmental aspects of residents of the Santa Cruz stream in the city of Breves, Marajó, Pará.

The study was carried out in the Santa Cruz creek, located in the municipality of Breves, in the mesoregion of Marajó, state of Pará. The municipality of Breves has an estimated population of 99,080 inhabitants and a territorial area of 9,563 km² (IBGE, 2016).11 The Santa Cruz stream is located in the outskirts of Breves, its source is located at the geographic coordinates 50° 29' 12'' W; 01° 40' 15''S and the mouth at 50° 29' 26'' W; 01° 41' 4''S. Currently, its bed runs along the Riacho Doce and Jardim Tropical neighborhoods on the right bank and in the Riacho Doce, Castanheira and Santa Cruz neighborhoods on the left bank (Figure 1). According to reports from residents, the housing process on the banks of the stream began in the 1980s, at the height of the timber industries installed in the municipality of Breves. The methodological procedures of this study are quantitative, basic in nature and descriptive research, as it is an investigation that relates the problem and describes the phenomena involved in it.12

For this, the study considered all the families living on the banks of the Santa Cruz stream, with 121 families on the right bank and 136 families on the left bank, totaling 257 families investigated. For one member of each family, a semi-structured questionnaire was applied, totaling 257 people who answered the questionnaire, representing 100% of the families in the study area. According to the ethical-legal precepts, this research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the State of Pará – Campus XII – Tapajós. CAAE: 63809516.9.0000.5168 whose approval opinion has the number 1.956.233. For the socioeconomic and environmental profile, a visit was made to each residence located on the banks of the Santa Cruz stream, from March 13 to April 14, 2017, on which occasion the study in question was presented to the community. Thus, one member of each family was invited to participate in the research and, after accepting the invitation, the Informed Consent Form (FICF) was delivered to the participant. The TCLE was read and signed, in accordance with the ethical-legal precepts of Resolution 466/12 – II of terms and definitions – II-23 (Brasil, 2012). Only after all the clarifications were made, the structured questionnaire containing 57 closed questions was applied.

All data collected with the questionnaire were compiled into spreadsheets and analyzed in tables in the Microsoft Excel 2016 program, in addition to being statistically interpreted by the G Test (non-parametric) test at 5% significance, using the Bioestat 5.3 software.

The banks of the Santa Cruz stream are home to 1,377 people (257 families), with 660 inhabitants (47.93%) on the right bank and 717 (52.07%) on the left bank. Of the total population, 694 (50.40%) are male and 683 (49.60%) are female (Table 1). Predominantly, 198 families are from the municipality of Breves and 59 families are from the municipalities of Portel, Melgaço, Curralinho, Anajás and Belém. Most residents of the Santa Cruz creek belong to the age group of 20 to 29 years old (n=257 inhabitants; 18.66%), followed by the age group of 10 to 14 years old (n=199; 14.45%) and of 15 to 19 years (n=177 inhabitants; 12.85%) (Table 1). Regarding education, the results show a low level of education, as the majority of the population (n=789; 57.30%) has incomplete primary education, 129 (9.37%) are illiterate and only 6 ( 0.44%) have completed higher education (Table 1). As for school status, 67 residents (4.87%) are enrolled in early childhood education, 426 (30.94%) in primary education, 98 (7.12%) in secondary education, 24 (1.74%) in education higher and 3 (0.22%) in literacy classes held by the Reference Center for Social Assistance (CRAS), totaling 618 of the inhabitants (44.39%) who attend the school (Table 1). As for the occupational activities of the population, 201 residents (14.60%) are engaged in informal work, developing services such as: general service provider, carpenter, bricklayer, stevedore, hairdresser, electrician, açaí juice seller, fruit seller. açaí/atravessador, charcoal, manicurist, shoemaker, day laborer, artisan and street vendor; 98 (7.12%) are retirees or Social Security beneficiaries or pensioners; 65 (4.72%) are salaried (bar and store attendant, sawmill, housekeeper, external delivery person, mechanic, metal worker, butcher, butcher, welder, cook, baker, clerk, nanny and watchman); 33 (2.40%) are public servants; and 54 (3.93%) of the inhabitants have other occupations such as motorcycle taxi driver, trader, shepherd, self-employed, fisherman and farmer.

|

Social profile |

Right bank |

Margin Left |

Total |

Percentage |

Test G p-value |

|

Gender |

|||||

|

Male |

337 |

357 |

694 |

50.40% |

0.6768 |

|

Feminine |

323 |

360 |

683 |

49.60% |

|

|

Age group |

|||||

|

< 1 |

21 |

20 |

41 |

2.98% |

|

|

1 to 4 |

68 |

47 |

115 |

8.35% |

|

|

5 to 9 |

96 |

61 |

157 |

11.40% |

|

|

10 to 14 |

98 |

101 |

199 |

14.45% |

|

|

15 to 19 |

72 |

105 |

177 |

12.85% |

|

|

20 to 29 |

123 |

134 |

257 |

18.66% |

0.0005 |

|

30 to 39 |

64 |

85 |

149 |

10.82% |

|

|

40 to 49 |

52 |

59 |

111 |

8.06% |

|

|

50 to 59 |

35 |

42 |

77 |

5.59% |

|

|

60 to 69 |

21 |

33 |

54 |

3.92% |

|

|

70 to 79 |

7 |

19 |

26 |

1.89% |

|

|

80 to + |

3 |

11 |

14 |

1.02% |

|

|

education |

|||||

|

Children under 5 who do not attend school |

73 |

47 |

120 |

8.71% |

|

|

Illiterate |

55 |

74 |

129 |

9.37% |

|

|

child education |

36 |

31 |

67 |

4.87% |

|

|

Incomplete Elementary School |

409 |

380 |

789 |

57.30% |

|

|

Complete primary education |

4 |

3 |

7 |

0.50% |

|

|

Incomplete high school |

48 |

86 |

134 |

9.73% |

|

|

Complete high school |

29 |

70 |

99 |

7.19% |

P<0.0001 |

|

Incomplete Higher Education |

6 |

18 |

24 |

1.74% |

|

|

Complete Higher Education |

0 |

6 |

6 |

0.44% |

|

|

Postgraduate studies |

0 |

two |

two |

0.15% |

|

Table 1 Characterization of the social profile of residents of the Santa Cruz creek, Breves, Pará from March to April/2017

More than 50% of the population residing in the Santa Cruz stream has an occupational activity without income contribution, as 164 (11.91%) are housewives; 584 (42.40%) are students from kindergarten to higher education and 178 (12.92%) have no occupation. Emphasizing that 120 are children under the age of 5 without going to school. As for the income of the families studied, considering the current salary of R$ 937.00 (nine hundred and thirty-seven reais), it was observed that the majority (n=186; 72.36%) of the interviewees had the same monthly income or less than the minimum wage, resulting from different work occupations (Table 2). It is also noteworthy that 1 family (0.41%) had an income of four minimum wages, coming mainly from the public service (Table 2). Of the total number of families residing in the Santa Cruz stream, 201 (78.21%) have a complementary family income. Among these, 193 (75.10%) supplement the monthly balance through assistance from the Bolsa Família Program and/or Social Security Benefit (sickness or disability allowance); 6 families (2.33%) make a salary supplement for the development of informal services; 1 family (0.39%) through the sale of some product (popsicles, chocolates, etc.) and 1 family (0.39%) complements the monthly income due to the employment relationship with the State.

|

Family income |

Source of income |

Occupation of family members |

Number of Families |

% |

|

≤1 salary |

Family allowance, informal service, salaried service, motorcycle taxi, commerce, social security benefit, closed-end insurance, pension, retirement and city hall. |

Informal worker, salaried farmer, fisherman, pastor, self-employed, motorcycle taxi driver, trader, beneficiary, retiree, pensioner, public servant, housewife and student. |

186 |

72.36 |

|

2 to 3 salaries |

Family allowance, informal service, salaried service, mototaxi, commerce, social security benefit, pension, retirement and city hall. |

Informal worker, salaried worker, farmer, fisherman, motorcycle taxi driver, broadcaster, sales consultant, nursing technician, trader, beneficiary, pensioner, retiree, public servant, housewife and student. |

70 |

27.23 |

|

4 salaries |

City Hall and State. |

Public servant, housewife and student. |

1 |

0.41 |

Table 2 Socioeconomics of residents of the Santa Cruz Breves creek, Pará: characterization of monthly family income from March to April/2017

Among the interviewed families, there are 56 families (21.79%) that have only one source of income, being 18 families (7.00%) that depend solely on retirement; 16 (6.23%) exclusively from federal government financial resources (Bolsa Família Program, Social Security Benefit (sick pay or Defense Insurance), 11 (4.28%) from informal work, 7 families (2.72%) depend on municipal public service income and 4 (1.56%) on salaried work.

As for the fishing activity on the stream, only 20 families claimed to carry out this practice, since, in most cases, this activity is carried out by children and adolescents and aims to support the family. The most common species of fish are jeju (Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus), yam (Geophagus brasiliensis), traíra (Hoplias malabaricus), piaba (Astyanax sp), tamuatá (Hoplosternum littorale), jacundá (Crenicichla lenticulata) and shrimp (Macrobrachium amazonicum).

Regarding the housing condition of the residents, 235 families (91.44%) have their own house on one of the banks of the Igarapé Santa Cruz, 10 (3.89%) live in a rented house and 12 (4.67%) families live in house provided by family members. Among the residences, 200 (77.82%) are built of wood, 16 (8.56%) of reused wood and only 7 (2.72%) were built of plastered masonry (Table 3). The residences have an average of 2.25 potential bedrooms, excluding kitchen and bathroom, with the family group comprising an average of 5.3 people per family. As for the origin of water for household use by family members in the study area, it was found that most (n=175) families (68.09%) use water from the stream, 78 (30.35%) use water of piped network and 4 (1.56%) use river water (Table 4). These families also use rainwater or water from the water truck. Water for household consumption comes from different sources, due to the precariousness or low structure of the water distribution system. Thus, only 92 families (35.80%) use piped water, 124 families (48.25%) fetch water from the water truck, from artesian wells or Amazon wells (common open well), river and stream and, 41 families (15.95%) buy filtered water (purchased from a distributor) or mineral water to drink (Table 4).

|

Type of construction of residences |

Right bank |

Left margin |

Total |

Percentage (%) |

|

Plastered masonry |

two |

5 |

7 |

2.72% |

|

unplastered masonry |

0 |

3 |

3 |

1.17% |

|

wood |

97 |

103 |

200 |

77.82% |

|

Wood and plastered masonry |

6 |

16 |

22 |

8.56% |

|

Unplastered wood and masonry |

4 |

5 |

9 |

3.50% |

|

reused wood |

12 |

4 |

16 |

6.23% |

|

Total |

121 |

136 |

257 |

100.00% |

Table 3 Housing conditions of the residents of the Santa Cruz stream, Breves, Pará, March to April/2017

|

Sanitation variables and characteristics |

Right bank |

Left margin |

Total |

Percentage |

Test G P-value |

|

Source of water for domestic use |

|||||

|

Igarapé water |

44 |

33 |

77 |

29.95% |

|

|

Stream water and rainwater |

44 |

49 |

93 |

36.19% |

|

|

Water from the stream and water from the water truck |

two |

0 |

two |

0.78% |

|

|

Stream water, river water and rainwater |

1 |

two |

3 |

1.17% |

P=0.1415 |

|

river water and rainwater |

two |

two |

4 |

1.56% |

|

|

Piped water |

26 |

48 |

74 |

28.79% |

|

|

Piped water, stream water and rainwater |

two |

two |

4 |

1.56% |

|

|

Total |

257 |

100.00% |

|||

|

Source of drinking water |

|||||

|

Artesian well |

13 |

13 |

26 |

10.12% |

|

|

Artesian well and river water |

3 |

0 |

3 |

1.17% |

|

|

Artesian well and water from the kite car |

5 |

two |

7 |

2.72% |

|

|

Artesian well and mineral water |

two |

1 |

3 |

1.17% |

|

|

Amazon well |

0 |

two |

two |

0.78% |

|

|

water from the kite car |

25 |

18 |

43 |

16.73% |

P=0.0820 |

|

Water from the kite car and water from the river |

5 |

4 |

9 |

3.50% |

|

|

river water |

17 |

13 |

30 |

11.67% |

|

|

Piped water |

38 |

54 |

92 |

35.80% |

|

|

Filtered water (purchased) |

8 |

13 |

21 |

8.17% |

|

|

Mineral water |

5 |

15 |

20 |

7.78% |

|

|

Igarapé water |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0.39% |

|

|

Total |

257 |

100.00% |

|||

|

sanitary sewage system |

|||||

|

black cesspool |

19 |

72 |

91 |

35.41% |

|

|

Direct on the igarapé |

5 |

30 |

35 |

13.62% |

P<0.0001 |

|

dry pit |

92 |

33 |

125 |

48.64% |

|

|

Without any type of exhaustion |

5 |

1 |

6 |

2.33% |

|

|

Total |

257 |

100.00% |

|||

|

Garbage collection |

|||||

|

public collection |

65 |

124 |

189 |

73.54% |

|

|

Public collection and thrown on the creek |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0.39% |

|

|

Public collection and burned |

18 |

8 |

26 |

10.12% |

|

|

played on the igarapé |

two |

0 |

two |

0.78% |

P<0.0001 |

|

burned |

33 |

4 |

37 |

14.40% |

|

|

burned and buried |

two |

0 |

two |

0.78% |

|

|

Total |

257 |

100.00% |

|||

Table 4 Basic sanitation characteristics of the residents of the Santa Cruz creek, Breves, Pará, March to April/2017

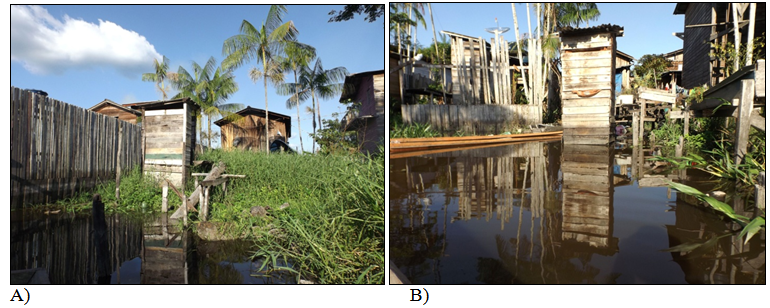

The treatment of water for consumption, according to the interviewees, is carried out by 198 families (77.02%), who use piped water, water from the water truck, river water, water from an artesian well and other sources. However, this treatment in most family members is only with a chemical (aluminum sulfate), in other homes, in addition to this product, residents use hypochlorite, but there are also homes that use only hypochlorite. Family members who filter or boil water are rare. Thus, 59 families (22.96%) consider that there is no need to carry out water treatment, as they come from artesian wells or filtered water or mineral water. As for the sanitary system, 87 residences (33.85%) have an internal bathroom and 4 (1.56%) have an external bathroom, both with toilet and waste destinations for black cesspools on the ground; 1 residence (0.39%) has an external bathroom with toilet and disposal of waste to the stream; 159 (61.87%) residences have an external bathroom without a toilet, which are built of wood with a hole in the ground without coating (dry pit) or built on the banks of the stream (Figure 2), where the feces are dumped directly into the igarapé and 6 residences (2.33%) do not have any type of sanitary sewage.

Figure 2 Aspect of the bathrooms in the Santa Cruz stream, Breves, Pará from March to April/2017. A) restroom located on the banks of the Santa Cruz stream. B) restroom located inside the Santa Cruz stream, next to the dishwasher.

It is noteworthy that the study area does not have a sewage system, and therefore, the organic waste of the population's physiological needs (stool and urine) is destined for dry pits (rustic house with direct excavation in the uncoated soil, intended for receive only excreta without water linkage), black pits (wells or holes dug in the ground, without waterproofing or with partial waterproofing, where raw sewage is disposed of by water) or directly into the stream (Table 3). However, 61 of the black pits and 46 of the dry pits are located 2 to 5 meters away from the stream. Regarding the garbage produced by the inhabitants, the results show that 189 families (73.54%) put household waste for public collection, 37 (14.40%) reported burning the garbage, mainly in the Amazon summer, where the water level of the igarapé is lower and 3 families (1.17%) dump their household garbage directly into the igarapé (Table 3). Although most of the population reported public collection and that it takes place twice a week, there was a lot of garbage thrown in the stream, including dead animals such as dogs and cats (Figure 3).

As observed in this study, the inhabitants of the right bank of the Santa Cruz stream have the lowest levels of education compared to those on the left bank (p<0.05). However, almost all people residing in the Santa Cruz creek have only basic education, which reflects the low level of education in the region, which contributes to the low human development index (HDI) recorded for the municipality of Breves, which is one of the smallest in the state of Pará.13

Studies carried out by Alves et al.,14 in rural communities in the municipality of Marapanim-PA, Araújo et al.15 in a quilombola community in the municipality of Ananindeua-PA and Guimarães, Pereira et al.16 in rural communities of the Caeté River basin in the State of Pará, which presented similar conditions, observed numbers close to those found. in Breves, which the authors classified as a low level of education. In this sense, it is important to emphasize that low education is a restrictive element to human development, due to the reduced ability to assimilate new knowledge, a condition that contributes to limiting people's social, economic and productive ascension.17,18

The population's low level of education allows us to infer that adolescents, young people and adults end up dropping out or giving up on their studies due to precarious living conditions. This condition supports their entry into the informal labor market. To the detriment of education, people only get jobs that require less qualifications, in which they earn less and, as a result, they are likely to be parents of children with no prospect of quality of life, reproducing poverty between generations.19 People with a low level of education belong to a context of responsibility aimed at meeting their living needs (subsistence), which makes them give up school life.20 Many people in this condition are part of a work reality with intense physical activity (manual work) and exhaustive work hours, mainly due to the need for a favorable source of income in the home economy and family support. Such work situation distances them from school and, in other cases, makes them simply lose interest in studying.

It is noteworthy that education is a decisive factor for the development of the individual and also of a society, as it promotes democratization, gives access to cultural heritage and higher positions in the select labor market, and must also consider that certain attitudes of an individual is influenced by the degree of institutional education.21 Therefore, when you have access to education, a range of possibilities opens up, whether in the material or intellectual aspect, in addition to providing new horizons and improving people's lives.22 However, according to Silva23 it is possible to state that one of the factors that most contributes to the lack of access to education in Brazil is the inequality of income distribution. This factor compromises the entire educational structure. Considering the aforementioned social aspects and considering the economic factor of the residents of the Santa Cruz creek, it can be admitted that the Bolsa Família Program is extremely important, since this benefit means an important income in the local economy,24 although the resident population of the Santa Cruz stream is living in a vulnerable situation. Study by Alves et al.14 carried out with rural communities in the municipality of Marapanim-PA, states that the financial resources destined to the low-income population, through the Bolsa Família Program, contributes to the increase in income and to the well-being of the families served. In this way, this financial resource serves to complement the residents' family budget.

There are situations in which the family income of residents of the Santa Cruz stream does not meet all household needs, even with the complement of financial assistance from the Bolsa Família Program. This fact is mainly due to the number of people in the residence, the lack of occupation by family members and the low level of education. These families often do not have their own daily support, needing, at times, to resort to fishing activities on the stream. In this activity, children and teenagers are the ones who support the family. Thus, it is necessary to implement new social policies and improve existing ones, as they are essential elements to achieve a better quality of life and a less unequal society.23

In the housing aspect, the characterization of the type of domicile and housing is an important indicator of the conditions and quality of life of the population.15 In this sense, the data in this study indicate, in general, that the homes of the interviewees have poor sanitary and infrastructure conditions, with the majority being rustic houses built of wood and some of reused wood, that is, these homes do not have full comfort and durability. In this regard, Pinheiro9 consider households to be durable, as at least two of the three housing components – roof, walls and floor – are made of durable materials, such as those found in masonry constructions.

The water distribution system in the municipality of Breves is the responsibility of the Sanitation Company of the State of Pará (COSANPA). However, unplanned urbanization caused a problem in the distribution of water to the neighborhoods further away from the city center. Thus, part of the population of brevense suffers from a lack of water, as is the case of most residents of the Santa Cruz stream. Therefore, the water used for consumption and domestic use by most residents, both on the right and left banks, without any statistically significant difference (p >0.05), comes from artesian or amazon wells, river , rain, kite car and the stream itself. Few people use piped water, as the distribution system is deficient.

The precarious situation of water distribution for the inhabitants of the Santa Cruz stream can lead to serious public health problems regarding the use of surface water, since, according to Marques et al.,25 the waters of this water body contain a high level of contamination by disease-causing organisms, according to these researchers, the level of contamination is so high that the surface waters of the aforementioned stream fall within the classification of the National Council for the Environment (CONAMA), Resolution No. 357/05 ( Brazil, 2005) as class 4, that is, they must be intended only for navigation and landscape harmony, being unsuitable for domestic use or consumption. The researchers detected concentrations of fecal (thermotolerant) coliforms between 4,352 NMP/100 mL at high tide and 111.Thus, the Santa Cruz creek, as a whole, receives punctual direct and indirect sewage discharges, which contributes to its high coliform values, as a result of dry and black pits located less than five meters away. In addition, the existence of toilets located on the banks or inside the stream should be considered, whose flow of human waste, together with rainwater and household water from other neighborhoods of the city, which are carried by sewage (open air) to the creek bed.Thus, the determination of the concentration of coliforms assumes importance as a parameter indicating the existence of pathogenic microorganisms responsible for the transmission of various diseases, including: worms, amoebiasis, giardiasis, cryptosporidiasis, typhoid fever, cholera and hepatitis A.26,27 It is important to highlight that the treatment of water for consumption from the river, stream or piped is not always carried out properly by the interviewed residents, since part of the population living in the Santa Cruz stream only uses aluminum sulphate, a chemical in which It is used for decanting dense particles present in water and not for combating microorganisms such as bacteria, protozoa and others.

Sanitation actions reduce the occurrence of diseases and prevent damage to the environment, especially to soils and water bodies. According to Kronemberger, Pereira, Freitas, Scarcello and Clevelario Jr (2011), 30.5% of Brazilian municipalities discharge untreated sewage into rivers, lakes or lakes, and use these receiving bodies for various downstream uses, such as in supply water, recreation, irrigation and aquaculture. These authors also admit that from these municipalities, 16% discharge untreated sewage into water bodies that are used downstream for human supply, corroborating the results obtained in this study for the Santa Cruz stream.

The municipality of Breves topresent only 6.1% of households with adequate sanitation and 2.9% of urban households on public roads with adequate urbanization with the presence of manholes, sidewalks, pavements and curbs. In these aspects, when compared to the 144 municipalities in the State of Pará, Breves is in the 91st and 57th position, respectively.(IBGE, 2010). These data demonstrate how deficient the city's basic sanitation is, however, this reality is present in most states that make up the Legal Amazon. Although there has been an increase in access to sanitation services, the percentage of sanitary coverage in the Amazon region is much lower than in other regions of Brazil.28

Another problem observed along the Santa Cruz stream is the presence of waste (organic, plastic, metal, glass), as well as on the sides or under the floor of the houses. This reality is opposed to the results obtained in the interviews, as there is a large amount of waste deposited in the water, for only three families who declared to dump their garbage in the stream. Therefore, it is clear that a large part of the population has neither sensitivity nor perception about the level of environmental degradation they are causing. In this context, it can be considered that Environmental Education is the most appropriate alternative to sensitize the population about environmental problems and promote changes in habits and behaviors that are harmful to the environment.29 Furthermore, The population's lack of awareness in relation to garbage increases the degree of vulnerability of people, not only in relation to the perception of health risk, but also in terms of public cleaning.30 Where people live influences their health and their ability to enjoy a prosperous life. Therefore, shelter, quality housing, clean water and adequate sanitary conditions are human rights and basic needs for a healthy life.

According to Law No. 11,445/2007, basic sanitation is the set of services, infrastructure and operational facilities related to four processes that include, drinking water supply, sanitary sewage, urban cleaning and solid waste management, and drainage and water management rainwater (Brazil, 2007). Thus, guaranteeing these rights is one of the concerns of policies to combat poverty and improve people's quality of life, as the quality, availability and accessibility of the population to basic sanitation are essential for human development.17 While people who are more financially privileged or wealthy generally inhabit adequate and relatively safe areas, from an environmental point of view, the less financially privileged (poor) most often live in precarious housing in places with situations of risk and environmental degradation, which generally they are accompanied by terrible conditions of urban and sanitary infrastructure,28,30 considering that they are often consequences of their own habits.

Studies similar to this one, carried out in quilombola communities,15 rural16 and in peripheries close to dams32 corroborate the results obtained in this study, with regard to the precarious conditions of housing, socioeconomic, infrastructure and environmental degradation. Thus, it is noteworthy that since the nineteenth century, there has been more evidence that the health conditions of a population are related to the characteristics of the social, economic, political, cultural and environmental context in which they live.33,34 As for the above, it can be admitted that the health problems arising from socioeconomic and environmental conditions in the Amazon region seem to be far from being resolved, as aspects such as poverty, precarious housing conditions, the inadequate urban environment and the Unhealthy working conditions are factors that negatively affect the quality of life of a population.34‒42

The Santa Cruz creek had its occupation in disarray as a result of the search for work/employment at the height of the timber industry in the municipality of Breves. This search triggered inadequate housing facilities on the banks of the stream. Today, the population living there has been suffering from the logging crisis and is looking for new income alternatives to meet the family's needs. Given this reality, it is evident that residents have low purchasing power due to the low level of education (schooling), which limits the options for better paid work. In this way, most of the population is induced to opt for informal work, which conditions the need for supplementary income, especially from the Bolsa Família Program. Most of the families studied do not have basic services, such as running water and adequate sanitary sewage. In addition, people living on the Santa Cruz stream need Environmental Education practices in order to minimize the environmental damage they cause to the stream. In this context, the action of government actors is necessary, so that public policies can be developed aimed at improving the quality of life of this population, whether through the implementation of sanitation infrastructure, generation of employment and income or encouragement of education . Given the specificities of the aspects diagnosed in this study, it can be inferred that most people living on the banks of the Santa Cruz stream, in general, have a low quality of life.

None.

The author delares there is no conflict of intetest.

©2021 Marques, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.