International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 1

Department of Forest Resources and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

Correspondence: Ekeoba Matthew Isikhuemen, Department of Forest Resources and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Received: December 24, 2019 | Published: February 14, 2020

Citation: Isikhuemen EM, Ikponmwonba OS. Okomu plateau forest and associated wetlands in southern Nigeria: status, threats and significance. Int J Hydro. 2020;4(1):31-40. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2020.04.00223

Okomu Plateau Forest consists of a central plateau and a surround crisscrossed by rivers/streams and creeks. The enclave is currently fragmented and turned into vestiges of secondary regrowth forest. This paper evaluates the state, anthropogenic threats and ecological significance of the heterogeneous ecosystems. Using the snowball sampling technique, information was obtained from primary participants – Government personnel and Oil Palm Company staff through key informants and focus group interviews. Recommendations obtained from primary participants were used to access/elicit information from secondary participants (retired staff; timber concessionaires and residents of 12enclave/fringing communities in the three thematic areas. Data were subjected to descriptive analysis. The outcome of socio-demographic survey revealed overall 243, mostly male adult respondents (77%) of average age 49years. The results on respondents’ views on the thematic areas investigated aptly revealed that: (a) both size and integrity of the forest had waned greatly signifying erosion of species and loss of fragile ecosystems; the concomitant decline in wildlife and aquatic biodiversity has negatively impacted livelihood systems and wellbeing of communities; (b) de-reserved of productive portions of the forest to other land uses; illegal logging/farming, and pollution of water/aquatic biodiversity by perilous effluents constitute serious drawback to ecosystem sustainability; and (c) the Okomu - Gilli Gilli - Ekewan - Ogba - Ologbo forest corridor constitutes important migratory route/refuge for wildlife, cultural repertoire for communities, and biodiversity repository for species and ecosystems. The semblance of intact/contiguous forest in the enclave currently resides in Okomu National Park and Okomu Oil Palm Company conservation areas. It is imperative that government ministries, departments and agencies shouldered with the responsibility of managing Okomu forests should entrench people- and eco-friendly policies/legislation that underscore good forest governance. Consequently, all agro-allied industries should engender the ‘polluter pays principle’ and livelihood enhancement programmes in their corporate responsibility agenda for host communities.

Keywords: biodiversity, de-reservation, encroachment, community livelihoods, perilous effluents, wildlife corridor

IUCN, international union for conservation of nature; CBD, convention on biological diversity; TSS, tropical shelterwood system

The phrase “Plateau Forest of Okomu” was coined and first used by E.W. Jones in 1955 to typify the environment, vegetation type and horizontal distribution of species; and in 1956, to explain reproduction and history of the Okomu Forest Reserve. The Okomu heterogeneous forest (which comprises rainforest, fringing/riparian, freshwater and lacustrine ecosystems) is part of the Guinea-Congolian class which supports a unique assemblage of biodiversity. The Guinea-Congolian region is a distinct phytogeographic region with a relatively homogenous flora.1 White defined ‘phytogeographic region’ as ‘a regional centre of endemism when it has more than 50% of its species confined to it, and when it has more than 1000 endemic species’. The ‘Plateau Forest of Okomu’ which is also called Okomu Forest Reserve is renowned for its richness in mahogany trees, e.g. Entandrophragma, Guarea, Khaya and Lovoa.2 In 1955, the Forestry Research Institution of Nigeria (FRIN) established two Permanent Sample Plots (PSPs) 83 and 85 in Compartments 65 and 95 respectively to monitor the ecology of the species and ecosystems in the protected area over an unspecified period of time.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines protected area (PA) as “a clearly defined geographical space recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”.3 But the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defines a PA as “a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives”. Redhead4 classified trees common to the forest in southern Nigeria into four utilization classes: Class I are species of major economic timber importance; Class II: Species of lesser importance; Class III: Species of possible timber importance; and Class IV: Species likely to be only of use for fuel, chacoal or industrial use. However, among the species listed, Hallea ledermannii (syn. Mitragyna ciliata), Lophira alata, Alstonia boonei, Symphonia globulifera and Uapaca sp. categorized under Group IIIB (species found in Okomu and Ologbo Forest Reserves) fall within the class of species of lesser use importance for timber).5,6

Okomu Forest Reserve is one of the 16 forest reserves in the rainforest region of Edo State, Nigeria where the famous but short-lived Tropical Shelterwood System (TSS) was carried out on a large scale. Of the several timber tree species common to Okomu which were of commercial importance, only two, Hallea ledermannii (Class I) and Alstonia boonei (Class II) were not poisoned during the TSS era which commenced in 1944 and terminated in the early 1970s.6,7 According to Kio,8 when TSS was first introduced in Western Nigeria, most of the large and relatively intact forest reserves were managed under 100-year rotation; the working circle being divided into Four Blocks, each with 25 annual coupes. The TSS in Nigeria was designed to run a 100-year cycle called Periodic Block (PB): 1945–1969; 1970–1994, 1995–2019; and 2020–2044; ironically, it was annulled at the end of the first Periodic Block (PB) in 1969 by the military (regional) governments in Western and Mid-west regions7. Presently, Okomu Forest Reserve, like most protected areas in Edo State, have been seriously impacted by diverse anthropogenic drivers of ecosystem degradation and species erosion. From the latter part of 20th century to contemporary times, the rainforest ecosystem comprising mangrove and coastal vegetation (12,782km2), freshwater communities (25,563km2) and lowland and dry deciduous forest (95,372km2).9‒12 and associated biota in southern Nigeria have not been greatly imperiled by diverse anthropogenic activities.

The long-term impact of logging, farming, oil/gas exploration/production and associated downstream activities, have been largely responsible for the monumental degradation of fragile ecosystems and loss of important commercial timber trees and fragile habitats.5,6 Despite the local extinctions of important species and spatial changes in water/landscapes; the wanton loss and/or conversion of productive biodiversity-rich forest ecosystems to sundry land-users, particularly oil palm and rubber plantations has been of great concern to ecologists. These activities, perhaps, remain the most heinous direct drivers of habitat/ecosystem fragmentation and genetic erosion and extinction of endemics species and other taxa restricted to short geographic ranges. Forest fragmentation is pivotal in the degradation matrix; it is undoubtedly hostile to biodiversity health because it constitutes a serious drawback to entry or exit of species into new areas and encourages isolation.13 Most terrestrial fauna, including avi-fauna which are pollinators and seed dispersing fruigivores are largely caught in the web of fragmentation, deforestation and degradation. If such animals avoid crossing open areas, they are unlikely to utilize fragmented habitats so the conservation value of such isolated forest patches will diminish.13

By the turn of the end of the 20th century, more than 60% of the entire forest estate in Okomu Forest Reserve had been dereserved or ceded to communities for expansion, oil palm conglomerates for tree crop plantation development, encroached upon by migrant cocoa farmers, illegally logged or appropriated by government for infrastructure and sundry development.14 The paper evaluates the current state, threats, and significance of Okomu Forest Reserve. Drawing on information from official (government) sources/reports, maps and results of past studies, the paper appraises the condition of biodiversity in the protected enclave against the anthropogenic drivers of ecosystem change; and suggests plausible solutions for resolving the identified drawbacks that threaten the wellbeing of the fragile and unique ecosystems as well as livelihood systems of the forest / wetland dependent communities.

Study area

Okomu Forest Reserve (size:1239km2) is located west of Benin City between Lat. 5° and 5°30΄E and Long. 6° 10΄ and 6° 30΄N. It is a significant component of Nigeria’s most diverse and productive ecosystems in terms of terrestrial and aquatic diversity. It was constituted by Notice 395 and Order of Gazette No. 27 of April 1912 while its extension was created by Order No. 13. The two instruments were converted by Order No. 26 of 1935.15 The forests was jointly managed by the defunct government of western Nigeria and Benin Native Authority (NA) administrations vide 1937 Forestry Ordinance, later renamed Forest Ordinance Cap 75 of 1948’.16‒18 In 1970, the Mid West government (which was created from the then government of western Nigeria in 1963) annulled dual forest management system and took over the control of all forest reserves although the instrument did not come into force until 1976.

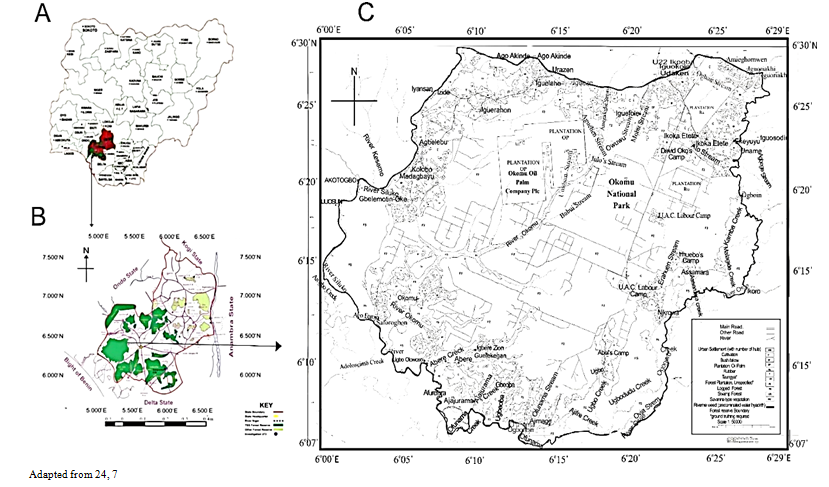

The topography, soil and vegetation of Okomu Forest Reserve have been described by several authors.19‒24 The enclave has a centralized plateau which is the source of Okomu River and several streams. The plateau is dominated by moist forest, riparian, freshwater and lacustrine ecosystems while the surround is crisscrossed by over 35rivers, streams and creeks. There are three major rivers, Siluko (which occupies the west boundary), Osse (on the east) and Okomu, which is located at the centre of the forest reserve. Overall, there are 41forest dependent communities in Okomu Forest Reserve; 27 of which are enclave settlements (i.e. communities living inside the forest reserve) (Figure 1). The major occupation of the inhabitants are fishing, farming, lumbering, hunting, NTFPs gathering and petty trading.

Figure 1 (A) Nigeria showing the 36 states with highlighted in red; (B) Edo State showing Forest Reserves (C) Okomu Forest Reserve showing the central plateau, enclave/peripheral communities and drainage systems.

Data collection and Analysis

Secondary data from maps, published reports/literature were obtained from Edo State Ministry of Environment, Benin City, Nigeria, and the internet. The study area was delineated into two: (a) riverine (i.e. communities living in territories that were permanently or fairly inundated all year round) and upland (i.e. communities that experience little or no inundation) for purposes of adequate representation and coverage. Thereafter, 12out of 41 fringing and peripheral communities were purposively selected based on accessibility. Three survey instruments – key informants’ and ‘focus group’ interviews and questionnaire,25,26 were used to elicit responses from participants in the different occupational groups. Using the snowball sampling technique, preliminary information was first obtained from the primary participants (government personnel and company staff) through key informants’ and ‘focus group’ interviews.27,28 Informants’ permission was sought with the help of primary participants prior to data collection conducted in offices and designated locations in communities and households. With recommendations from the primary participants, the secondary participants (retired staff; timber concessionaires and residents of 12enclave/fringing communities) were accessed and prioritized while making sure there was adequate representation across stakeholder groups. The use of key informants’ and ‘focus group’ interviews side by side semi-structured questionnaire was to allow respondents to freely elect and volunteer responses while minimizing bias.29 Before the administration of questionnaire, participants were first prompted with a list of questions in 13sub-themes drawn from three thematic areas (Table 1; Appendix).

|

Participant |

Survey instrument/Allotment |

|||||||

|

Category |

No. of persons |

Response |

||||||

|

Govt./other Staff |

2, 3 |

24 |

24 |

|||||

|

Retired Staff |

2, 3 |

20 |

16 |

|||||

|

Timber Concessionaire |

2, 3 |

20 |

15 |

|||||

|

Sub-total |

64 |

55 |

||||||

|

Community* |

|

Issued |

Retrieved |

Farmers |

Logger |

Hunter |

Fisher |

Others |

|

Madagbayo |

1, 3 |

25 |

22 |

8 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

|

Nikrowa |

1, 3 |

25 |

24 |

7 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Okomu |

1 |

15 |

13 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

Ajakurama |

1, 2 |

20 |

20 |

10 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

Udo |

1, 2, 3 |

30 |

28 |

13 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Gbelebu |

1 |

20 |

17 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

Iguelaho |

1 |

15 |

12 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

Iguerahon |

1 |

10 |

8 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

Urhezen |

1,2 |

10 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Arakhuan |

1, 2 |

15 |

12 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Iguagbado |

1, 2 |

15 |

13 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

IzideNoke |

1, 3 |

15 |

12 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

Sub-total |

215 |

188 |

76 |

49 |

26 |

14 |

23 |

|

|

Grand total |

279 |

243 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thematic areas and sub-themes |

Forest community (n=188) |

Government personnel(n=24) |

Retired staff (n=16) |

Timber concessionaire (n=15) |

Harmonic mean |

Total (n=243) |

|

Status of FR |

92 % |

100 % |

88 % |

80 % |

89.67 % |

92 % |

|

Decline in Forest Size |

48 % |

67 % |

31 % |

53 % |

46.03 % |

49 % |

|

Encroachment into FR |

58 % |

67 % |

19 % |

40 % |

36.43 % |

55 % |

|

Loss of Timber/NTFPs |

33 % |

63 % |

25 % |

67 % |

39.56 % |

37 % |

|

Rarity of Wildlife Res. |

54 % |

38 % |

31 % |

27 % |

35.04 % |

49 % |

|

Reduced Livelihoods |

55 % |

33 % |

19 % |

13 % |

22.47 % |

48 % |

|

Anthropogenic Threats |

89% |

96 % |

88 % |

60 % |

80.50 % |

88 % |

|

Dereservation |

34 % |

67 % |

25 % |

53 % |

38.76 % |

38 % |

|

Invasion by cocoa farmers |

62 % |

71 % |

44 % |

67 % |

58.93 % |

62 % |

|

Illegal Logging |

52 % |

55 % |

56 % |

80 % |

59.02 % |

54 % |

|

Pollution by effluent |

28 % |

42 % |

11 % |

27 % |

21.34 % |

28 % |

|

Wildlife/Fish decline |

36 % |

46 % |

17 % |

13 % |

21.59 % |

33 % |

|

Significance of Okomu FR |

60 % |

100 % |

70 % |

67 % |

71.58 % |

65 % |

|

Biodiversity repository |

24 % |

79 % |

50 % |

33 % |

38.23 % |

32 % |

|

Wildlife Refuge/Corridor |

15 % |

67 % |

56 % |

40 % |

32.14 % |

24 % |

|

Culture/Livelihood |

75 % |

54 % |

44 % |

13 % |

30.42 % |

67 % |

Appendix Spread of sub-themes under thematic areas identified in the study

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Standard deviation and harmonic mean were used to clarify concurrence and/or dissension in opinions among respondents. Prior to data collection, the study design was pretested28 in a pilot survey involving 24participants selected randomly from three pilot communities, timber concessionaire association and government personnel. Data were collated and analysed using descriptive statistics.

The socio demographic information on respondents revealed a gender biased outcome with an overwhelming male adults participants (Table 2). A significant number of the respondents whose ages span 41 to 50years were married. The results further showed that majority of the respondents were educated beyond the secondary school level and had lived or worked in Okomu Forest Reserve for over 20years (Table 2).

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

187 |

76.95 |

|

Female |

56 |

23.05 |

|

|

Marital status |

Single |

38 |

15.64 |

|

Married |

164 |

67.49 |

|

|

Widow(er) |

41 |

16.87 |

|

|

Age |

<30 |

29 |

11.93 |

|

31 - 40 |

57 |

23.46 |

|

|

41 - 50 |

88 |

36.21 |

|

|

51 - 60 |

37 |

15.23 |

|

|

>60 |

32 |

13.17 |

|

|

Educational attainment |

Non formal |

17 |

7 |

|

Primary |

36 |

14.81 |

|

|

Secondary |

73 |

30 |

|

|

Graduate |

117 |

48.19 |

|

|

Job-related Experience in Okomu |

<10 |

65 |

26.75 |

|

20-Nov |

59 |

24.28 |

|

|

>20 |

119 |

48.97 |

|

Table 2 Socio demographic information of respondents encountered during the study in Okomu Forest Reserve

Current State of the forest

The views expressed by participants on the current condition of the forest and allied resources in Okomu Forest Reserve were varied across the different domains that were investigated. The respondents among government/company staff (67%) were quite forthright in their opinions on the increasing decline of the forest in terms of size and integrity; they ascribed the reduction in size and decline in resources to the encroachment and unauthorized occupation by illegal cocoa farmers, excision by government and subsequent conversion of significant portions of the enclave for purposes of community expansion and/or agricultural expansion/development by oil palm conglomerates. However, the timber concessionaires (67%) and forest enclave communities (63%) were most disturbed over the aggregate increase in species erosion and concomitant loss of both timber and non-timber forest resources. A significant number of respondents from enclave/peripheral communities (45%) underscored the consequences of the destruction of the fragile ecosystems which they claimed was having a negative impact on the wellbeing of wildlife/aquatic biodiversity and quality of water bodies (45%). The respondents (55%) surmised that the destruction and erosion of species and loss of fragile ecosystems that constitute the plateau forest were having ripple effects on the livelihood systems and wellbeing of forest enclave and fringing communities (Figure 2).

Anthropogenic threats

A greater number of the participants who were largely timber concessionaires (80%) and government/company personnel (71%) affirmed that the portions ceded to agro-allied industries and individuals were the most productive in terms of species diversity and richness (in timber, non-timber forest products and wildlife resources). They asserted that from the early 1980s through the 1990s till date, there have been ceaseless demands for de-reservation by corporate organizations, communities and individuals for purposes of agricultural intensification and expansion as well as development of infrastructure. Thus the foregoing were primarily responsible for the excision of over 13% of the productive portions of Okomu Forest Reserve to intending applicants by the end of 2017 (Figure 3 & Table 2). Harping on the consequences of the invasion of the entire enclave by illegal cocoa farmers under any guise, several respondents – including government/company staff (71%) and timber contractors (67%) – expressed their discontent, suing that it would ultimately exterminate endemic species and fragile ecosystems. However, while the timber contractors (80%) felt disillusioned with the poor effort of government in curbing the menace; they were quick at drawing the attention of government, communities and other stakeholders to the consequences of discharging perilous effluents on to water bodies by oil palm conglomerates and the overall impact on aquatic biodiversity (Figure 3).

Significance of Okomu forest and related wetlands

Majority of respondents – comprising of community residents (75%) and government company staff/community (54%) – were quite disturbed over the dwindling ecosystem functions; noting that it was impacting negatively on livelihood systems as well as cultural repertoire of the forest dependent communities (Figure 4). Among the respondents, government/company staff expressed the greatest concern that the functional role of the forest reserve as wildlife refuge/corridor (67%) and biodiversity repository (79%) might be lost forever if no drastic action was taken to reverse the trend, particularly now that the ecosystems have not been completely lost (Figure 4).

The designation ‘Okomu’ as used in ‘Okomu Community’, ‘Okomu Forest Reserve’15 and ‘Okomu Plateau Forest’19 was derived from “River Okomu”. River Okomu is the most centralized of the three major rivers – River Osse (on the east) and River Siluko (on the west) that drain Okomu Forest Reserve – which originates from the central plateau in the protected area and flows south-west wards, emptying into networks of creeks/creeklets (Figure 1). But the appellation ‘Plateau Forest’, coined and originally used by E. W. Jones in 1955 might have originated from the bewildering and unique features of the intricate ecologies of diverse forest vegetation types on the centralized highland surrounded by networks of rivers/rivulets culminating in creeks/creeklets.

The land use practices in Okomu Forest Reserve have been intensely altered overtime – to the extent that there is significant deviation from the land use classification by Ajayi.31 Proforest32 reported that ‘logging occurs in the swamp forest at certain times of the year, particularly by chainsaw operators both nearby and distant communities; thus posing a major threat to the continued provision of critical ecosystem services of the swamp forests. Given the fragile nature of the heterogeneous ecosystems, logging and lumbering activities would ultimately lead to irreversible damage – reduction of water/nutrient holding capacity of the soils and stream flow rate, dislocation of river catchments and acceleration of river bank erosion as well as runoff and sediment deposition, and suppression of infiltration and contamination of nutrients and aquatic wildlife and associated resources. The results of previous anthropogenic disturbances in Okomu Forest Reserve are manifest: local extinction of species, changes in water/landscapes, past forest management systems and conversion of fragile ecosystems to sundry land-uses have had excruciating impacts on these fragile habitats/ecosystems; thereby resulting in fragmentation, genetic erosion and serial extinction of endemics and rare species.6

Most respondents, e.g. government/company personnel (67%) and concessionaires (53%) expressed their displeasure over the de-reservation and/or conversion of >50% of Okomu Forest Reserve to sundry land uses (cf. Figure 3 & Table 2). De-reservation, lack of coherent forest policy, prevalence of illegal logging and harvest of Non Wood Forest Products (NWFPs), chronic under-funding, under-staffing and conflicting roles among of government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs), excessive bureaucracy, lack of harmony and inter-sectoral coordination and overall absence of reliable data for planning and implementation of forest development and regeneration activities, are the major constraints to sustainable forest management and biodiversity conservation in Nigeria’.33 The de-reservation of forest land for purposes of community expansion, commercial agriculture and the development of infrastructure assumed a frightening dimension in most lowland rainforest states, including Edo State during the latter part of the 20th Century.6 According to Eguavoen,34 a significant portion of Okomu Forest Reserve was ceded to multinational agro-based companies (notably, Okomu Oil Palm Company and Osse River Rubber Estate) for development and expansion of large tree crop plantations several years ago”. But while some multinational timber companies (e.g. African Timber and Plywood held large concessions in Okomu from the 1960s through mid-1980s) were leaving, they left behind a large number of staff and families whose only option was to take to farming in the forest reserve, thus resulting in the overall reduction of the forest.2 The ensuing contest for land/space might have compelled the Okomu Forest Reserve communities to evolve coping and management/use practices as well as rules and community governance systems, interlaced with customary norms, to convert and use forest based resources in a fashion most suitable for them; thus reflecting the evolution of unique cultures of heterogeneous communities in different ecosystems.35

|

S/No. |

Land use type |

Description |

Land area (km2) |

Size of area invaded (km2) as at 2017 |

Remark/Source of threats |

|

1 |

*Okomu National Park. |

ONP: constituted a National Park by Decree No. 46 of 1999. Main aim was to conserve of biodiversity, ecosystems, species, wetlands, river catchments and, artifacts. |

202 |

>20 |

Cocoa farmers, illegal logging and poaching. |

|

2 |

*Buffer zone to Okomu National Park |

Area set aside as safeguard to biodiversity in ONP |

21 |

10 |

Communities/cocoa farmers |

|

3 |

Production forest |

Concessions (256 ha) are allocated by the Forestry Department; forest re-entry in the state is three years. |

51.2 |

89.6 |

Cocoa farmers, illegal logging and poaching |

|

4 |

Forest and tree crop plantations |

28.9 |

12.2 |

Illegal Farming |

|

|

5 |

*Okomu Oil Palm Company. |

Oil Palm Plantation and Rubber Development |

216.99 |

0.08 |

Illegal cocoa farming/ logging & poaching. |

|

6 |

* Excised for rubber and oil palm companies |

Area ceded for rubber and Oil Palm plantation in BC 10 but later revoked by State Govt. |

50 |

Concessions revoked in 2015 |

|

|

6 |

*Osse River Rubber Estate |

Excised by Govt. for Rubber Plantation Development |

45 |

||

|

7 |

*Community / individual use |

Community expansion, private tree crop plantations |

30.8 |

||

|

8 |

Rivers/streams, lakes and creeks |

Wetlands/forest seasonally or permanently inundated |

370.3 |

||

|

Total |

|

|

1016.19 |

131.9 |

|

Table 3 Land use practices in Okomu forests

*Areas officially de-reserved by Edo State Government for agricultural, community and sundry uses

With regards to encroachment into, or invasion of the forest reserve, by tree crop/cocoa farmers and illegal loggers, there was unanimity among respondents – government/company personnel (71%), concessionaires (67%) and community residents (62%) that their activities spell doom for the existence and sustainable management of OFR. They surmised that the combined impact of cocoa farming and uncontrolled logging was not only causing the erosion of endemic fauna and flora, but stifling and ultimate extermination of biodiversity. There was a consensus among respondents that illegal logging was impeding log movement control and effective monitoring of timber exploitation by field staff: (a) it is becoming extremely difficult for uniformed patrol staff to navigate the network of rivers/streams/creeks because lumbering has overtime become an explosive enterprise where loggers carry dangerous weapons during operations. Although the opinions among respondents – government/company staff and forest reserve communities showed more concern on the extent to which the aquatic biodiversity had been ravaged by oil palm and rubber conglomerates who discharge noxious wastes/effluents into water bodies; they were greatly disturbed by the declining health of fragile ecosystems and decreasing fishery resources (Figure 3).

There was a convergence of opinion across occupational groups – communities (62%), government/company staff (71%) and timber concessionaires (67%) – that the ‘the invasion of OFR by cocoa farmers from neighbouring States in Southern Nigeria was largely orchestrated by elites from enclave and/or fringing communities who have unlimited access to government or could muster resources and political will and patronage to stem any political or economic backlashes. But while the invitation of cocoa farmers might have been borne out of selfish interests in complete disregard to the long term consequences (notably, degradation of fragile ecosystems and erosion of biodiversity), the benefactors were unmindful of the overriding impact on the livelihood systems of forest dependent communities”. On the part of government, the need to shore up internally generated revenues, particularly from forest resources (e.g. timber) might have influenced its decision to play safe by opting for political agreement. To this end, the state government took a decisive action in 2004 by tinkering with the extant forest policy on forest reserve administration in order to accommodate the cocoa farmers as taungya farmers. Ultimately, the arrangement was discarded because the farmers, in defiance of the accord reached with government, made further incursions into the forest reserve; thereby constituting themselves into “army of occupation” in areas under government control and concessions that have long been ceded to multinational agricultural companies and entrepreneurs for oil palm and rubber development.

The word “Taungya” is a traditional Burmese word which underscores the practice of raising forest tree seedlings side by side arable agricultural crops. When the annual-and somewhat bi-annual arable crops are harvested, the forest tree seedlings/saplings are tended until maturity. Plantations and surrogate forest stands were successfully established through the ‘taungya system’ which was introduced in Nigeria during the mid-1900s and flourished up to the early 1980s. The difference between the two versions of ‘taungya system’ is that the old taungya allowed only annual crops and ensured optimum protection for the planted trees over a period of time while the new taungya inspires the destruction (through gradual removal) of mature trees after using them to nurture the young cacao seedlings which require understorey shade during juvenile growth stage. Besides, the farmers maintain itinerant lifestyles – they reside in camps and work in their cocoa plantations inside the forest reserve.

The affirmation by the timber concessionaires that “illegal and uncontrolled logging had flourished over the years; thus turning most portions of the forest reserve, especially the productive parts into vestiges of degraded or secondary regrowth forests” appears to buttress Jone’s19 earlier findings that ‘logging in Okomu Forest Reserve started over a century ago although with strict adherence to coordinated working plan’. The consequences of intensive and uncontrolled logging in the fragile rainforest and associated wetlands include loss of ecosystems, erosion of endemic fauna and flora taxa and ultimately the recurring spells of occupational shifts and related drawbacks that tend to defy quick fix or short term solutions. In effect, the rural poor who derive sustenance chiefly from forest/freshwater resources often contend with unending and mutually reinforcing livelihood travails where poverty and environmental degradation feed into each other.6 Not only are the poor disproportionately dependent on nature and biodiversity for their livelihoods, they are also inexplicably vulnerable to the losses of their limited ability to pay for substitutes.36 But government/company staff (67%) and retired workers (56%) were most apprehensive about the stifling consequences of further fragmenting of the famous Okomu-Gilli Gilli-Ekewan-Ogba-Ologbo wildlife corridor on the fragile ecosystems’ capacity to sustainably provide diverse ecological and socio-cultural services (including positive externalities). Okomu Forest Reserve together with four others (namely, Gilli Gilli, Ekewan, Ogba and Ologbo forest reserves) constitute an indispensable wildlife corridor, particularly for primates (e.g. the endangered white-throated guenon, Cercopithecus erythrogaster), which are endemic to the area.

It is apt to suggest that both government and sundry users of environmental goods and services should plough back a significant portion of their benefits toward cushioning or mitigating the negative effects of their activities. The ‘polluters pay principle’ or ‘payment for environmental services’ is an instrument that addresses environmental externalities through variable payments made in cash or kind, with a land user, provider or seller of environmental services responding to an offer of payment by a private company, non-governmental organization (NGO) or local or central government agency.37 Both government/company staff (70%) and to a lesser extent retired workers (50%) strongly expressed their concerns about the important role that Okomu Forest Reserve plays as biodiversity repository; remarking that conscious efforts must be geared toward sustaining this important function, otherwise both the dwindling biodiversity (including the blemished wildlife resources) and livelihood systems of forest dependent communities would be further imperiled (Figure 4). According to Szaro,38 the best time to restore an ecosystem or species is when it is still available.

Okomu Forest Reserve offers diverse ecosystem services – provisioning (e.g. food, water, timber, non-timber forest products, fiber, ethno-medicine, etc.); regulating (e.g. carbon capture/sequestration, pollination, biological pest control, floods, disease, wastes, and air/water quality, etc.); cultural (e.g. recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits); and supporting (e.g. soil formation, photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, etc.).39,40 Other non-measurable and intangible benefits that are obtainable from OFR include: recreational, aesthetic, cultural and spiritual services. These are critical for fulfilling people’s emotional and psychological needs.41 Among these so called intangible benefits are regulatory services, otherwise called “invisible services” – because they are hard to measure and are not directly consumed by humans – which are the services most impacted by human transformation of fragile ecosystems; and, if lost, may impose high costs on society and may be extremely expensive to repair or recover.42

The complex networks of the diverse water bodies and unique features of associated vegetation types might be responsible for the seasonal or somewhat permanent inundation experienced in OFR all year round. These permanently or periodically inundated forests are specialised nutrient rich, self-sustaining ecosystems which are unique repositories of biodiversity – they serve as fawning ground, nesting or brooding sites for sedentary and facultative aquatic wildlife including mammals and fish.6 Wetland ecosystems, including seasonally waterlogged floodplains, freshwater marshes, swamps forests and estuaries, play critical roles in sustaining the livelihood systems of forest and wetland dependent communities. In addition to water purification, control and absorption of flood waters and release of runoffs; wetland ecosystems also prevent eutrophication by absorbing nutrients while retaining sediments and toxicants.43 They also yield a range of products – e.g. fish, fodder, timber, non-timber forest products, agricultural crops, etc. – acting as shores stabilizers while preventing coastal storms and erosion as well as backlashes. For example, the lacustrine and freshwater ecosystems positively influence the quality and quantity of hydrological flows; support ecological regimes in aquatic ecosystems; trigger and improve ‘spongy effect’ in river catchments and support energy flow and nutrient recycling (Figure 5).

Isikhuemen6 reported that of the total size of 79000ha freshwater ecosystem in Edo State, Okomu Forest Reserve accounts for 21, 324ha (or 24%). The lacustrine and freshwater swamp forest ecosystems are seasonally flooded and chiefly inundated during the wet season; dominated by flora species, e.g. Anthocleista vogelii, Carapa procera, Chrysobalanus orbicularis, Grewia coriacea, Garcinia spp.; specialized and self-sustaining; provide fawning ground as well as brooding and nesting sites for sedentary and facultative fauna species.6 Hughes and Hughes45 surmised that lacustrine ecosystems and permanently flooded swamp forests (i.e. forest inundated all year round) support diverse species e.g. Alstonia, Hallea, and Raphia spp.

Okomu Forest Reserve is a significant part of the Guinea-Congolean regional centre of endemism; it typifies Nigeria’s old growth rainforest relic straddling unique ecosystems. It consists of a central plateau and a surround drained by a network of rivers, streams and creeks. The size of the enclave – which is home to over 41 forest/wetland dependent communities – has been greatly altered. There is rarity of timber and allied resources; encroachment and illegal logging are rampant and impacting negatively on biodiversity as well as the livelihood systems/wellbeing of forest/wetland dependent communities. The entire land/waterscape has been turned into secondary regrowth forest. Biodiversity is increasingly being plundered without hindrance while pollution through the discharge noxious wastes/effluents into water bodies is impinging on aquatic ecosystems and water quality. The corridor formed by Okomu, Gilli Gilli, Ekewan, Ogba and Ologbo Forest Reserves which hitherto served as refugia for wildlife, especially primates; and cultural repertoire for forest dependent communities is largely fragmented. The relic or semblance of relatively intact and somewhat contiguous rainforest vegetation now reside in the Okomu National Park and conservation areas owned and managed by Okomu Oil Plc.

The current state of ecosystem health in Okomu Forest Reserve is not only alarming but desires concerted efforts by all stakeholders to reverse the trend of damage. There is need for both federal and state governments to revisit extant policy/law in line with current realities. To this end, all federal and state ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) responsible for management and conservation policies for Okomu National Park and the larger forest reserve must, as a matter of urgency, endeavor to foster people- and eco-friendly legislation that underscore good governance. Besides, all the agro allied industries whose activities impinge on the wellbeing of ecosystems goods and services should be compelled to imbibe the ‘polluter pays principle’. In addition, they must ensure that participatory and community based management approaches (that underpin incentivized alternative livelihood system) are entrenched into their corporate responsibility agenda.

The authors are grateful to all community representatives who participated in this study. Special thanks to all government personnel and timber concessionaires who, as primary participants, provided relevant information and support in identifying the communities and secondary participants.

The authors have no competing interests.

None.

©2020 Isikhuemen, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.