International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Mini Review Volume 2 Issue 6

1Seedbed of Geological Heritage Research, Industrial University of Santander, Colombia

2Research Group in Basic and Applied Geology, Industrial University of Santander, Colombia

Correspondence: Carlos Alberto Ríos-Reyes, Research Group in Basic and Applied Geology, Industrial University of Santander, Colombia

Received: November 15, 2018 | Published: December 4, 2018

Citation: Gelvez-Chaparro JE, Herrera-Ruiz JI, Zafra-Otero D, et al. Geotouristic potential in karst systems of santander (Colombia): the begining of right geoducational and geoconservational practices. Int J Hydro. 2018;2(6):713-716. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2018.02.00148

In Santander, Colombia, there is a large variety of extraordinary landscapes, among which the karst systems stand out, and are one of the most representative in the region. That is due to their geological, faunal and archaeological significance. The caverns and caves represent unique natural laboratories and incredible landscapes from which, visitors can gain exceptional knowledge about the karstic dynamics. Furthermore, in many cases, learn about the history of their ancestors, which is a synonym of a geotouristic potential. Geoeducation promotes the conservation and protection of places of geological interest, promoting that society has a vast, reliable and critical knowledge about the natural and cultural heritage of its region. By implementing concepts such as conservation, sustainability and geoeducation, the practice of geotourism can be carried out in order to generate awareness among visitors and adventurers, without forgetting the local community. In that way the concepts previously mentioned will greatly contribute to the development of Santander.

Keywords: karst, caverns, geoeducation, geotourism

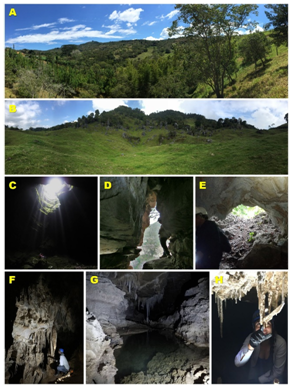

In most cases, karstic terranes have relevant significance and scientific, economic, educational, recreational and cultural applications. Karstic terranes are extensive and millions of people worldwide live in them. Therefore, the management of karstic systems has to identify singular areas which allow putting into practice models which combine both conservation and development. The geological heritage is the tool that allows the selection and identification of these areas.1 The underground karst has been a subject of curiosity since the begging of time. Over time, society has taken advantage form karstic systems in many ways, such as, recreational, touristic, and cultural. It is important to take into account that karstic landscapes commonly have both a remarkable surface biodiversity and an underground biodiversity associated with them. This biodiversity contains a large variety of species worldwide. However, the endemicity and diversity are the rule especially in isolated karsts in the tropics.2 Caves are extremely fragile ecosystems with high vulnerability to human impact in which a massive influx of assistants will affect their pristine state. Thus, a special management of these terranes under certain policies that seek for their geoconservation is required.2‒5 Santander is located in the north-eastern area of Colombia, it is also part of the Andean region, on the western flank of the eastern mountain range, which is one of the most important structures in terms of the diversity of caves in the country (Figure 1). The area previously mentioned is considered for many as the main axis in terms of caves diversity.6 Santander extends over an area of approximately 30537 . This area also has a diversity of geomorphological landscapes that conserve part of the department's geological and cultural history, making them places of scientific and tourist interest at the same time (geological heritage). Karstic systems in the Santander occupies a large area, and this area has a huge geological variety. In the last speleological cadastre, which was carried out by Muñoz-Saba et al.,7 different karstic manifestations were registered in the department of Santander reporting two hundred and six geoforms including: caves, caverns, sinkholes and chasms. Nevertheless, there are only researches in less than 25% of them. By implementing responsible geotourism practices the notorious karst wealth of the department could have an important contribution to the sustainable development of the region. The promotion of the tourist caves allows divulging the geological heritage, stimulating scientific and environmental education actions. Moreover, it allows the strengthening of economic sectors and stimulates the creation of legally protected areas.8,9

Figure 1 Variety of karstic landscapes in Santander. (A) Exokasrtic landscape in Zapatoca, Santander; (B) Exokasrtic landscape. Giant field of karst towers, “The karst town” in El Peñón, Santander; (C) Collapsed roof of 150 m high, called “El Corazón del Mundo” in El Peñón, Santander; (D)The end of “Cueva El Borboso”, pseudo karstic cave with archaeological evidence in Los Santos, Santander; (E) Main entrance of the Lucrecia cave in Rionegro, Santander; (F) Endokarstic landscape in El Nitro cave in Zapatoca, Santander; (G) Underground spring in The Golden Cave in El Peñón, Santander; (H) Speleothems in The Golden Cave in El Peñón, Santander.

During the new millennium, geotourism has become an important activity at local, national and international scale. Geotourism’s main objectives include the promotion of the geological knowledge, and the implementation of campaigns which generate awareness regarding the geological heritage and the need for its conservation. Moreover, the diversification and sustainable development of the tourism industry. In turn, geotourism has become a subject of research, where the main research is concentrated in Europe, East Asia, the Middle East, and South America.10 The great diversity of karstic landscape elements is positioned as one of the most purposes for the development of geotourism, recognizing this as an important and necessary strategy of sustainable use of karstic landscape. At the same time with such diversity, these unique landscapes allow the practice of a large variety of activities. These activities, in turn, are intended for a wide variety of people.11,12 The karst wealth of Santander is quite abundant, in Santander, there are cavities emerging in very varied places from warm weather with tropical forests at 800 meters above sea level to cold weather at about 3200 meters above sea level. The existence of tourist caves depends on different determining factors, such as conditions of the physical environment, the existence of infrastructure, specific attractions; the relationship between the demand and the influx of public to the cave; profile of the interested people and researches of the negative impacts.13 The same cavern can have different kind of uses. However, according to Lobo et al.,11 among the main speleotouristic possibilities we find the following activities:

Those caves that allow an easy access is known as show caves,13 Currently about 500 of the largest Show Caves in the world receive numerous visitors a year. Weather all activities related to the existence of a Show Cave (transport, accommodation, guides and others) are considered, close to 100 million people would be directly and indirectly involved in economic benefits (Cigna & Forti, 2013). In Mexico we have the Cacahuamilpa Caverns, a well-recognised show cave which receives on average about 350000 visitors a year.15 In some areas of Santander where peleotourism practices are carried out, it is common to find evidence of the destruction of this Irrecoverable Natural Heritage (Figure 2). In some cases, the vandalism even has caused the destruction of speleothems, cave sealing for conservation reasons and instability, graffities in the roofs and walls and archaeological material desecrated and looted, and biodiversity threatened by inappropriate use of tourism in different areas of Santander. Here, as well as in many parts of the world, the lack of scientific information is a problem. Therefore, the propose of using tools such as brochures, maps, didactic infographics has been considered for further studies.15

Due to the importance for scientific and general community, geological and geomorphological features and processes are crucial parts of the environment and are worthy of conservation and sustainable management.16 The agents and conditions that contribute to the evolution of the karst must be taken into account. For example, the interaction between lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and atmosphere. This implies that karstic regions are highly sensitive to any change from the environmental point of view. The extremely vulnerability of karstic ecosystems makes geoconservation a mandatory topic to guarantee the integrity of the entire system, because any damage to one element could dramatically affect the other ones.1 To work on a geo-ethical practice is an essential part of geotourism. Geoethic in terms of the development of geotourism promotes geoeducation for a better understanding of the processes involved in the karstic systems formation, with the aim of developing critical awareness. This allows making responsible decisions on issues related to natural heritage, especially in young people.17 Geotourism should be guided by ethical principles to ensure that commercialization does not destroy harmony with nature. To be sustainable, geotourism must promote and strengthen geo-conservation practices, without coming into conflict with the economic benefits for communities. Geo-conservation must strongly ensure both the particular benefit of community and the preservation of environment.17 Geo-tourism does not only support the geo-conservation of outcrops, but also it must provide economic, cultural, social benefits for both communities: visitors and locals. Thus, whether visitors have an awareness and respect for geo-heritage, it is more likely to conserve and help to manage sustainably the heritage of the area.17 It is important to analyse the caves affection to consider the best way to address the issue. Some geo-conservational models have been considered in this paper, however, the model for El Nitro Cavern in Zafra et al.18 stands out for the authors of this paper. In this model, some protected zones are selected (high geological, biological and patrimonial interest) which will be enabled exclusively for scientific purposes. The concept of geological heritage closely linked to the geological elements that are part of the natural heritage and its management in terms of conservation and promotion for its use, because they constitute a resource themselves.1

Geoeducation is the learning approach throughout life, around several areas related to the planet Earth, promoting scientific knowledge and the sustainability of its inhabitants, encouraging society behaviour changes.19 The principal role in terms of geoeducation has been played by UNESCO since its beginning in 1945, by generating ideas in the same topic. Scientifics or students can just keep investigating, publishing researches while the surrounded communities will remain away from the outcomes of those studies.20 A natural cavity allows to correlate diverse classroom concepts and to represent them in the field, by using the cave as a "model".20 Moreover, cavities can easily be used as an academic tool from the viewpoint of many basic and scientific disciplines, due to the numerous field them involve. For example, chemistry, biology, physics and social sciences, just to name a few. Nowadays, geoeducation has been carried out in some areas of Santander such as: Los Santos, Zapatoca and El Peñón. This through training activities with local tour guides, focusing on geoconservation issues, karst genesis, exogenous and endogenous karstic expressions, paleoclimate and karst evolution alongside with basic geological notions and principles. These educational campaigns have generated awareness about the importance of underground ecosystems and their preservation during time. The campaigns previously mentioned have been supported by didactic material such as maps, brochures, fossils, espelothems, thin sections, images in scanning electron microscope, scientific-informational banners. These activities are expected to be replicated in other areas of Colombia together in order to offer visitors a valuable and meaningful experience, fully addressing contemplative, Adventurous and educational speleotourism. In that way, the right balance between recreational, geoacademic and geoconservative practices will be able to coexist in complete harmony (Figure 3).21,22,23

Figure 3 Geoeducational practices carried out in different areas of Santander. (A) The Virgen cave in El Peñon, Santander. It is mainly used for religious speleotourism proposes; (B‒C) Adventurous and contemplative speleotourism practices in El Nitro cave, Zapatoca, Santander; (D‒E) Geoeducational campaigns in different areas of Santander, Colombia; (F) Diffusion of geoeducation activities in karst systems in Santander.

This work is part of the activities advanced by the Research Seedbed in Geological Heritage of the Research Group in Basic and Applied Geology of the Industrial University of Santander for its awareness about importance of scientific divulgation and its support in the different journeys for geoeducation in the department of Santander. Special thanks to the Geoespeleology Group for its courage and dedication to conquest the last place to discover: the underground worlds.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2018 Gelvez-Chaparro, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.