International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 1

1Technical Service Center, US Bureau of Reclamation, USA

2Department of Civil Engineering, National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan

Correspondence: Yong G Lai, Technical Service Center, US Bureau of Reclamation, Denver, USA, Tel 01-303-445-2560

Received: February 05, 2018 | Published: February 26, 2018

Citation: La YG, Wu K. A numerical modeling study of sediment bypass tunnels at shihmen reservoir, taiwan. Int J Hydro. 2018;2(1):72-81. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2018.02.00056

Many reservoirs in the world were built years ago and losing their storage capacities. At Shihmen reservoir, Taiwan, topological, geological and seismological factors greatly increased sediment delivery to the reservoir. A large amount of fine sediments entered the reservoir in the form of turbidity current. Due to limited desilting facilities, majority of the sediments deposited near the dam, leading to a significant loss of the storage capacity. Moreover, extreme typhoon events produced sufficiently high sediment concentrations that water supply was interrupted, causing social and economic problems. A number of sediment management projects have been planned for the reservoir in order to extend the reservoir life and maintain water supply, but few tools are available to understand the effectiveness of the proposed projects. In this study, a two-dimensional (2D) layer-averaged turbidity current numerical model is presented and used as a reservoir evaluation tool. The sediment bypass tunnel is the study focus as it has been proposed as an important sediment removal measure. The model is presented and then validated using the available physical model data. Once validated, the model is used to evaluate the effectiveness of two proposed sediment bypass plans. Further, the physical model scale effect is investigated using the numerical model which is often unknown. This study serves as a further verification that the newly developed 2D turbidity current model is robust and useful for practical project applications.

Keywords: Turbidity Current, Layer-Averaged 2D Model, Reservoir Sedimentation, Reservoir Sustainability, Sediment Bypass, Bypass Tunnel

Many reservoirs have been constructed worldwide. After the construction, a reservoir will continue to be filled with sediment over time, causing storage loss, reducing water supply reliability, and impacting infrastructure such as marinas, outlet works, and turbine intakes.1 Reservoir sedimentation affects all levels of the reservoir and all storage allocations by use, whether it is conservation, multi-use, or flood pool.2 The rate of reservoir sedimentation is site specific and may vary from an average annual storage loss of 2.3 percent in China to 0.2 percent in North America.3 In the western United States, half of the Reclamation’s reservoirs are over 60 years old, nearly 20 percent are at least 80 years old, and 7 percent are already over the design life of 100 years.1 According to the RESSED (REServoir SEDimentation) database,4 the 83 surveyed Reclamation reservoirs have had an average annual storage loss of 0.19 percentage since 1990. More in-depth discussions of reservoir sedimentation issues and the management measures were provided.1,5–9 This study concerns with the sedimentation issue at Shihmen reservoir, Taiwan. Topological, geological and seismological factors have increased sediment delivery to the reservoir. Due to limited desilting facilities, a large amount of fine sediments did not pass through the reservoir, leading to a significant loss of the storage capacity. Moreover, extreme typhoons produced sufficiently high sediment concentrations that water supply was interrupted, causing social and economic problems. A number of sediment management projects have been planned by the Taiwan government to extend the reservoir life and maintain water supply. In particular, multiple sediment bypass tunnels are to be designed and constructed to address the sedimentation issues. A combined field, physical model and numerical model studies are being used to assist the planning and design of the sediment bypass tunnels. However, few numerical models are found adequate to simulate the turbidity current processes in the reservoir and sediment sluicing predictions through the outlets. In this study, the aim is to develop and present a two-dimensional (2D) layer-averaged turbidity current numerical model that is suitable for sediment bypass prediction in practical reservoirs. The model builds on the work of Lai et al.10 The new contributions of this study are threefold. First, the model of Lai et al.10 is further calibrated and validated against a practical reservoir (Shihmen) that has a combined sluicing gates and sediment bypass tunnels. The effort lends credence to the numerical model that is being considered for real-time forecast applications at the reservoir. Second, the model is extended to simulate two proposed sediment bypass plans and results are compared with the existing condition scenario. The results allow an objective evaluation of the bypass tunnels. Third and final, the physical model scale effect is investigated which helps planners to determine the appropriate use of the physical model results.

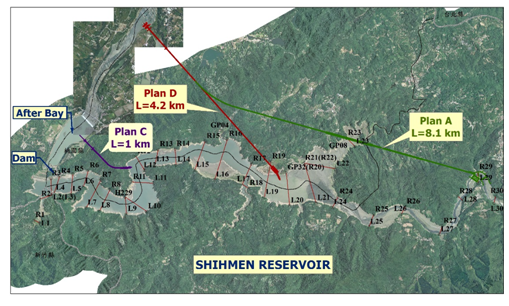

Shihmen reservoir is located in the middle of Dahan River, one of the three primary tributaries to the Tansui River in Taoyuan City, Taiwan (Figure 1). The construction of the dam started in 1956 and the reservoir started to store water in May, 1963. The reservoir since serves multiple purposes: power generation, municipal and irrigation water supply, flood protection, and recreational use. The reservoir has a dam height of 133 m, length of 360 m, and a design storage capacity of 309 million-m3 at the maximum water elevation of 245 m. At full storage, the reservoir has a longitudinal length of 16.5 km and a surface area of 8.0 km2. Its effective storage is about 252 million-m3. Shihmen reservoir has experienced much higher sediment supply in the past two decades than the original design estimate. Main factors were the geological weathering owing to climate change and much increased landslide and soil erosion due to the 921 earthquake in 1999.11 Increased sediment supply led to a rapid loss of the reservoir capacity. In the early years, more than 100 upstream check-dams, about 35 million-m3 storage, were built to block the coarse sediments from entering the reservoir. By 1996, after Typhoon Herb, check dams were almost fully filled.12 Herb alone carried about 8.7 million-m3 of sediments into the reservoir. The damage of Balin Dam by Herb, along with the 921 earthquake in 1999, aggregated the reservoir deposition problem. The total annual sediment entering the reservoir is now four times more than that before the 60s. Due to limited sediment desilting facilities, the reservoir is quickly losing its storage capacity. For example, the bed elevation near the dam rose from 160 m in 1964 to 185 m in 2005 and more than 32% of the reservoir storage capacity has been lost by 2009.12 The remaining reservoir life is estimated to be less than 25 years if nothing is done.12 At Shihmen reservoir, water is clear under normal conditions. It may become very turbid during large typhoon events (Figure 2). Coarser sediments deposit mostly on the upstream delta while finer suspended sediments move towards the dam. It has been found that the fine sediments entering the reservoir may plunge to the bottom to form a turbidity undercurrent.11 Water near the surface may remain clear while a turbid current moves over the bed. With very large typhoons, the undercurrent may surge to the water surface and become visible from the top (Figure 2). When sediment concentrations near the surface are higher than what can be handled by the water treatment plant, the water supply may be interrupted. Such a devastating event indeed occurred in August 2004 when typhoon Aere hit the area. The watershed that drains into the reservoir experienced a total of 973 mm rainfall during August 23 to 26, producing a peak discharge of 8,954 m3/s in the Dahan River that flowed into the reservoir. According to one estimate,12 typhoon Aere alone caused a total sediment deposit of 27.9 million-m3 in the reservoir and a loss of about 11% of the reservoir capacity. Moreover, water supply was stopped for 18 days impacting more than one million people. Taiwan government responded to the Aere disaster at Shihmen reservoir. Immediate relief measures were implemented to restore the water supply. A number of mid- and long-term projects were authorized to ensure water supply and to sustain the reservoir life. Various sediment management options have been proposed.5,9 Among them, the sediment bypass tunnels are the main long-term sediment desilting strategy.

Figure 3 Locations of five existing dam outlets that may be used for sediment sluicing; they are named Spillway, Flood Diversion, Powerhouse Outlet, Permanent Channel and Shihmen Intake.

Figure 4 Locations of the three proposed sediment bypass tunnels: Plan A, C and D; L stands for the distance from the intake to the downstream sediment discharge location.

Outlets |

Main parameters |

Values |

Spillway |

Design Discharge |

11,4000 cms |

|

Crest Elevation |

235 m |

|

Gate Height & Width(6) |

10.6 m x 14 m |

Flood Diversion |

Design Discharge |

2,400 cms |

|

Sill Elevation |

220 m |

|

Tunnel Pipe Diameter(2) |

9 m |

Powerhouse |

Maximum Discharge |

137.2 cms |

|

Bottom Elevation |

173 m |

|

Pipe Diameter (2) |

4.57 m |

Permanent Channel |

Maximum Discharge |

34 cms |

|

Bottom Elevation |

169.5 m |

|

Pipe Diameter |

1.372 m |

Shihmen Intake |

Design Discharge |

18.4 cms |

|

Bottom Elevation |

193.55 m |

|

Pipe Diameter |

2.5 m |

Table 1 Key existing sluicing outlet parameters at Shihmen reservoir

Field studies have been carried out at Shihmen reservoir by the research team at the National Chao-Tong University who documented the results in a number of reports.11,16–18 The field study investigated the transport behavior of high sediment concentration flows at the reservoir using both manual and automated instruments. The suspended sediment concentration monitoring stations were set up at various reservoir outlets and a number of cross sections. For example, data were collected for six typhoons between 2008 and 2010 in the study of.11 The field data were used to produce the relationship between the upstream discharge and sediment load, reservoir capacity change, sediment-related water quality, and sediment transport patterns. Furthermore, particle size distributions of the suspended sediment and bed sediments before and after typhoon events were obtained. A comprehensive set of field data were obtained during typhoon Fung-Wong. The warning for Fung-Wong was issued at 2:30 am, July 27, 2008, on the land and removed at 11:30 am, July 29, 2008. The field measurement started recording at 18:00 pm, July 27. The measured data showed a peak flow discharge of 2,039.2m3/s and a peak sediment rate of 305,664 ton/hour. Estimation based on the data showed that the total sediment volume that entered the reservoir was about 664,520 m3 and the total volume out of the reservoir was about 85,852 m3, which resulted in the sediment sluicing rate of only 13% for the event. This set of data, however, was deemed inaccurate based on the study by Lai & Huang15 who simulated the Fung-Wong event in the field. The field measurement of turbidity currents is very challenging and has a high uncertainty with most existing measurement techniques due to limited variables measurable, hazardous conditions in the field, the presence of debris, and the high costs. The field studies reported in11 showed that some of the automated instruments failed or the data measured were unrealistic. Physical model studies of turbidity currents have been carried out to assist the planning and evaluation of the sediment management projects at Shihmen reservoir since the field study is inaccurate and limited to the existing condition scenarios.12 The Shihmen physical modeling study used a 1/100 scale undistorted model, was based on the Froude number similarity, and occupied a lab space of 120 by 20 m. The physical model covered about 15.5 km longitudinal length of the reservoir and upstream river section; the upstream boundary was located between XS-30 and 31 (Figure 5). The physical model was used to study the turbidity current characteristics, determine the sediment sluicing properties under the existing conditions, and evaluate the different bypass tunnel plans. Typhoon Aere, occurred in August 2004, was used as the modeling event. The physical model topography was obtained from the field topographic survey conducted in December 2003. The sediment was taken from those deposited near the powerhouse outlet of the reservoir; the sediment diameter ranged from 4 to 8μm. The scenarios tested in the physical model include:12 (a) the existing condition; (b) the modified existing condition; and (c) three bypass tunnel plans conditions (Plan A, C, and D).

The physical model results of12 are used in this study to first calibrate and validate the numerical model of Lai et al. 10 The results, however, are only roughly applicable to the field due to the scaling issue. Froude number scaling was recommended and used by Middleton.19 The preclusion of the Reynolds number similarity, however, may lead to an over-emphasis of the viscous effects.20 Other important phenomena would also be scaled incorrectly such as the surface tension, interfacial processes between the clear and turbid interfaces, sediment transport processes, and mobile-bed dynamics. In particular, the sediment size used by the physical model was too high and it was expected that the physical model may under-estimate the sediment sluicing rate through the reservoir outlets at least during the falling limb of the flow hydrograph.12 Therefore, a key design parameter is the scaling effect of the physical model results. In this study, the validated numerical model is further used to estimate the scaling effect which is otherwise unavailable with other means. Numerical model results, combined with those from the field and physical model studies, may be used to inform the selection and design study of sediment management projects. The usefulness of the numerical models has been recognized early by Middleton21 & Bradford22 who provided good reviews on the subject. More recent reviews on the numerical modeling of turbidity current may be found in.23–25

Model description

The 2D layer-averaged turbidity model of Lai et al.10 named SRH-2D, is adopted to simulate the sediment desilting processes at Shihmen reservoir under various conditions. The set of 2D layer-averaged equations are an extension of the one-dimensional (1D) model by Toniolo et al.26 and may be expressed as:

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

In the above, t is time; x and y are horizontal Cartesian coordinates; h is current thickness; and V are layer-averaged current velocities in x and y directions, respectively; , , and are depth-averaged stresses due to turbulence and dispersion; g is gravitational acceleration; and are bed shear stresses; is current mixture density; is layer-averaged volumetric sediment concentration; is bed elevation; is top elevation of the current; is porosity of the bed sediment; and is fall velocity. Auxiliary variables include: total velocity ; current specific gravity with and the sediment density and the ambient density. The remaining variables and parameters are defined later. The term on the right hand side of (1) is the entrainment from the ambient fluid and is assumed to be proportional to the current velocity. The entrainment coefficient is empirically determined using the expression developed by Parker et al.27

(6)

In (6), the bulk Richardson number is defined by which is related to the densimetric Froude number by .

A very important term is the interfacial drag between the upper ambient fluid and the current represented by the terms in (2) and (3). The drag is represented as a fraction of the bed drag in the current model. The bed drag components in the x and y directions are computed by:

(7)

In the above, the bed drag coefficient. In this study, the drag coefficient is used to represent the total drag combining both the bed and interfacial drags due to the lack of reliable interfacial friction relations. The depth-averaged dispersive stresses are calculated with the Boussinesq formulation as:28

(8a)

(8b)

(8c)

where is kinematic viscosity of the mixture and is the eddy (or dispersion) viscosity. The eddy viscosity is computed with the depth-averaged parabolic turbulence model;29 that is, with the coefficient ranging from 0.02 to 1.0 and the friction velocity .

The sediment concentration equation (4) is based on the mass conservation; its right hand side includes the bed erosion potential ( ) and the sediment deposition rate. The deposition rate is determined by the near-bed concentration ( ) that is related to the depth averaged concentration through . The shape factor is generally a function of grain size and is computed by the following expressions30

(9)

In (9), and are the medium and geometric means of the sediment. The erosion potential is based on the equation of Engelund and Hansen.31 The equation is expressed as:

(10)

A number of numerical methods may be used to solve the above governing equations. For example, Imran et al.32 used the finite-difference method and the structured quadrilateral meshes, Choi33 reported the use of the finite-element method and the triangular meshes, and Bradford and Katopodes20 adopted the finite-volume method and the structured quadrilateral meshes. Lai et al.10 proposed and demonstrated a finite-volume based model applicable to unstructured meshes. A key advantage of the Lai et al.10 model is that an arbitrarily shaped element method was adopted which facilitated the representation of practical reservoirs. The same flexible mesh methodology was demonstrated earlier by Lai28 to solve 2D open channel flows. A detailed presentation of the numerical algorithms is omitted herein and readers may refer to Lai et al.10 It is sufficient to report that the present numerical method starts with a solution domain covered with an unstructured mesh with arbitrary polygons. All dependent variables are stored at the geometric centers of the polygonal cells. The discretization of the governing equations is achieved through Gaussian integration over polygons. The final discretized equations are put into a linearized form so that flow and sediment variables may be computed in all mesh cells through a semi-implicit time marching fashion.

Model inputs

Numerical model inputs are described in this sub-section as most model inputs are the same. Differences for different cases will be mentioned when each case is presented later. The solution domain of the numerical model is the same as that of the physical model (Figure 5) and the corresponding 2D mesh and the initial bathymetry and terrain of the numerical model, representing the reservoir in December 2003, are shown in Figure 6. The mesh consists of 33,008 cells and 33,621 nodes and was sufficient to produce mesh independent solutions based on the study report of Lai & Huang15. The field surveyed bed elevation data made in December 2003 was used for both the physical model construction and the numerical model initial terrain. The average slope from the upstream boundary to the dam face is about 0.375%. Three types of model inputs are needed: initial and boundary conditions, process model parameters, and numerical modeling parameters. The initial condition represents the clear water state of a reservoir so no additional information is needed. The primary boundary conditions are the flow hydrograph and sediment supply rate at the upstream boundary, and the conditions at all reservoir outlets. At the upstream boundary, the field measured time series flow discharge and sediment concentrations are utilized. For the typhoon Aere event, they are plotted in Figure7. The simulation starts at 2:00 am, August 24, 2004 and ends at 21:00 pm, August 26 (a total of 67 hours in the field and 6.7 hours in the physical model). At each reservoir outlet, flow discharge through the outlet is used along with two user-supplied parameters that are related to the sediment sluicing properties of the outlet (the sluicing multiplier and exponent). The outlet flow discharge is from the measured data if available or estimated from the known gate capacity. The sluicing multiplier and exponent are determined from the measured data or through model calibration. Details of the boundary conditions at an outlet were discussed by Lai et al.10,15 Only a few inputs are needed with regard to the process models and the related model parameters. They are as follows: (a) The turbidity current drag coefficient is 0.055; (b) The turbulence and dispersion are represented by the parabolic model with a coefficient of 0.1l; (c) The sediment transport capacity adopts the Engelund-Hansen equation;31 and (d) The entrainment rate is computed by the formula of Parker et al.27 The turbidity current sediment is simulated as a single size class with a medium diameter of mm and a specific gravity of 2.7 according to the test by the physical model study. The simulation is carried out from 2:00 am on August 24, 2004, assuming the reservoir is initially clear (i.e., zero suspended sediment without turbidity current). The time step is 0.2 seconds (2 seconds in the prototype), which produced time-step independent solutions.15

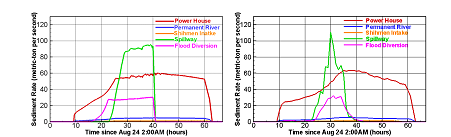

Model calibration under the modified existing condition

A baseline physical model study was carried out under the modified existing conditions which represented the existing reservoir after the completion of the permanent channel and powerhouse intake projects.12 A numerical modeling study was also performed for the same physical model case for model test and validation.10 It was shown that the calibrated model produced results in good agreement with the measurement data.10 Key modeling results of the modified existing condition are summarized below as they are used as the baseline to compare with the present study of assessing the impact of the bypass tunnel plans. The calibrated model under the modified existing condition predicted well the turbidity current travelling speed when compared with the data. For example, the model predicted that it took 9.25 hours for the current front to reach the powerhouse while it was 9.3 hours for the physical model. The turbidity current moved at almost a constant speed of about 0.448 m/s in the prototype. A comparison of the predicted and measured sediment rates through all outlets is shown in Figure 8. The overall agreement between the numerical and physical models is reasonable. Major discrepancy is in the prediction of sediment rate through the spillway and the flood diversion tunnel. The predicted rate through the spillway is much higher than the measured data due primarily to the use of a constant full-capacity discharge of 5,800m3/s by the numerical model. The discharge at the spillway was not measured during the physical model testing and no attempt was made in the study to reduce the spillway flow for a better comparison. The predicted total sediment through the flood diversion tunnel was also higher than the measured one. It is mainly caused by the difference in gate opening timing and duration. For example, the predicted start of sluicing is at time 16 hours when the current reached the outlet (which is accurate based on the current movement comparison). However, the sediment concentration wise in the physical model is about 7 hours later than the numerical model. It is possible that the gate was actually opened 7 hours later than the current arrival in the experiment. The total sediment volumes delivered to and sluiced out of the reservoir by each outlet are compared in Table 2. The total sediment passed through the reservoir is about 55.9% and 45.1%, respectively, with the numerical model and the physical model. The higher predicted passing efficiency by the numerical model is due primarily to the higher predicted sediment out of the spillway and the diversion tunnel discussed above.

Model results under the sediment bypass tunnel conditions

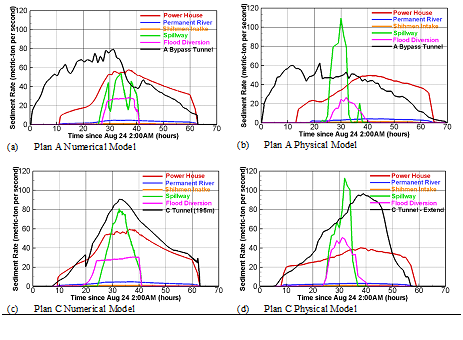

Two bypass tunnel plans, A and C, are simulated with the present numerical model and results are reported and discussed. The purpose is twofold. First, the SRH-2D turbidity current model may be further validated against the physical model data under the combined sluicing outlets and sediment bypass tunnel condition. A fully validated model is being considered as a real-time forecast tool for the reservoir operation in the future. Second, the simulations serve as applications of the model to obtain the sediment desilting rates with the bypass tunnel plans which are important to evaluate and refine the different plans. Plan D is not done as it was found that there was an intake sucking vortex present during the physical model test (personal communication with the engineer who carried out the physical experiments). A sucking vortex may significantly reduce the sediment diverted through the tunnel; such a phenomenon cannot be simulated accurately with a 2D model. So comparison of Plan P will be fruitless. The zoom-in views of the bypass tunnel representations in the numerical model are shown in Figure 9 (refer to Figure 4 or their locations in the model domain), and the key parameters of the bypass tunnel plans are listed in Table 3. Note that only local modifications of the baseline 2D mesh are performed to add the tunnels into the model and the remaining mesh is undisturbed. Two sets of numerical modeling are carried out. The first set intends to match the conditions of the physical model tests as much as the data allow. The purpose is to calibrate and validate the numerical model against the measured data. The second set is to simulate the two bypass tunnel plans using the same model inputs as the baseline modified existing condition case except for the extra outlet added to represent each specific bypass tunnel. The purpose of the second set is to compare the model results of the bypass tunnels with the baseline modified existing condition case. This way the differences in the numerical model results are due purely to the added bypass tunnel. Note that an advantage of the numerical model is that exactly the same upstream boundary conditions, as well as other model inputs, may be used and applied. It was not possible for the physical model experiments; actually somewhat different upstream flow and sediment rates were resulted for each experiment test. The first set of two numerical simulations predict the sediment rates through each individual outlets and their time series variations are compared with the physical model data in Figure 10. The second set of simulations are obtained for comparison with the baseline modified existing condition case and the predicted total reservoir sediment desilting rate as well as the rates through all outlets are summarized in Table 4.

Results in Figure10 show that the numerical model is capable of predicting the time series sediment rates through all outlets and the model results are in general agreement with the measured data. Both the sediment rate magnitudes and trends are captured reasonably by the numerical model at most outlets. Some discrepancies do exist. For example, a major discrepancy of Plan C is that the sediment rate through the powerhouse is much over-predicted by the numerical model. The peak of the sediment rate through the C tunnel is predicted to occur about 5 hours earlier than the measured data. We are unsure whether this discrepancy is related to the different gate opening. A better quantitative comparison is not achieved due to several reasons. Chief among them is that the flow rate and the timing of gate open and close were not recorded for some outlets during the physical model test. Only the design flow rate and timing are used by the numerical model. The gate opening is assumed to occur as soon as the turbidity current front reaches the gate during the numerical modeling. This may explain some of the discrepancies between the numerical and physical model results. Other uncertainties exist. For example, the numerical model of Plan A uses the same conditions as the modified existing condition case but the physical model had somewhat different incoming discharge and sediment rates at the upstream. The recorded upstream data of Plan A were incomplete and exhibited high uncertainty according to the engineers who carried out the physical model test; they, therefore, were not used by the numerical model. Comparisons between the bypass tunnels with the baseline modified existing condition case provide the important data to assess the effectiveness of the proposed bypass tunnels. An advantage of the numerical model is that exactly the same mode inputs (e.g., upstream conditions) may be applied to different cases. Differences in model results are then due purely to the added bypass tunnel. The numerical results in Table 4 show that both bypass tunnel plans are effective in increasing the sediment desilting out of the reservoir. The sediment bypass rate at the tunnels is predicted to be 35.5% and 31.4%, respectively, for Plan A and C; while the desilting rate for the entire reservoir is 73.0% and 71.4%, respectively, for Plan A and C. This compares with the total reservoir desilting rate of 55.9% predicted by the baseline modified existing condition. The additional increase of more than 16% for the bypass tunnel desilting rate is deemed important for the reservoir sediment management at the site. Although the physical tests were done using somewhat different upstream conditions, they may be used to compare with the numerical model findings qualitatively. The physical model tests showed that the sediment bypass rate was about 31.5% and the desilting rate for the entire reservoir is about 68% for both bypass tunnels. These data are within 10% of the numerical model results. The physical model results showed that the two bypass tunnel plans resulted in about 23% additional desilted sediment rate. The higher desilting rate of the baseline modified existing case predicted by the numerical model than the physical one is due probably to the prolonged gate opening at several outlets. Overall, the total sediment desilting rates predicted by the numerical model are in a better agreement with the measured data than the time series results suggest.

Physical model scale effect

The physical model results had been used to assist the selection of final bypass tunnel plans for the sediment management projects at Shihmen reservoir. A key question in the selection process was about the scale effect of the physical model. With the numerical model calibrated and validated, the model may be used estimate the scale effect since it can be generally assumed that the numerical model is scalable. For such a study, a set of new simulations are carried out using the prototype (field) scales. All the model input parameters are kept the same as those of the physical model scale. The only differences are: the spatial scale of the field is 100 times larger than the physical model scale and the mean sediment diameter in the field is increased to 0.01 mm based on the field measured data.

The predicted sediment desilting rates through each outlet, as well as the total rate, are compared in Table 5. The model results show that the scale effect is not significant. For example, the desilting rates at the field scale through all outlets are about 10% higher than those at the physical model scale. Therefore, the sediment desilting rates obtained by the physical model tests may be under-estimated at Shihmen reservoir.

Figure 6(a) The 2D mesh used by the numerical modeling. (b) The initial bed elevation (labels are in meter) of Shihmen reservoir based on the survey data in December 2003 with the physical model scale. The flow is from tight to left in the figure.

Figure 7 Flow discharge and sediment concentration at the upstream boundary of the model domain which entered the Shihmen reservoir during typhoon Aere (time zero is at 2:00 am, August 24, 2004).

Figure 8 Comparison of predicted and measured sediment rates through all sluicing outlets (time and sediment rate are in the prototype scale). (a) Numerical Model Prediction. (b) Measurement by the Physical Model

(a) Plan A (b) Plan C

Figure 9 Zoom-in views of the two bypass tunnel locations represented by the numerical model; the bed elevation is in the physical model scale.

Figure 10Comparison of the redicted and measured sediment rates through all outlets for the two bypass plans.

|

Total into (106 m3) Reservoir |

Total Out of Reservoir (106 m3) |

Power House (106 m3) |

Spillway (106 m3) |

Flood Diversion (106 m3) |

Permanent Channel (106 m3) |

Shihmen Intake (106 m3) |

Numerical Model |

10.93 |

6.11 |

3.31 |

1.72 |

0.754 |

0.265 |

0.0569 |

55.84% |

30.30% |

15.70% |

6.90% |

2.42% |

0.52% |

||

Physical Model |

10.97 |

4.95 |

3.18 |

1.02 |

0.43 |

0.259 |

0.0593 |

|

|

45.12% |

29.00% |

9.30% |

3.92% |

2.36% |

0.54% |

Table 2 Summary of total sediments moved into and out of the reservoir under the modified existing condition.

Bypass plans |

Location |

Tunnel length (km) |

Design Flow |

Tunnel opening dimensions |

||

Sill elevation |

Height (m) |

Width (m) |

||||

Plan A |

Upstream |

8.1 |

16,000 |

225 |

8 |

56 |

Plan C |

Near Dam |

1 |

12,000 |

195 |

10 |

10 |

Table 3 Summary of key bypass tunnel parameters in the prototype scale

|

|

Bypass tunnel |

Power house |

Spillway & flood |

Perm. channel |

Shihmen intake |

Total |

Modified Existing |

Numerical |

N/A |

30.30% |

22.60% |

2.42% |

0.52% |

55.90% |

Physical |

29.00% |

13.20% |

2.36% |

0.54% |

45.10% |

||

Plan A |

Numerical |

35.40% |

22.90% |

12.60% |

1.83% |

0.41% |

73.00% |

Physical |

31.40% |

22.80% |

13.00% |

1.78% |

0.38% |

69.40% |

|

Plan C |

Numerical |

31.40% |

25.30% |

12.10% |

2.10% |

0.46% |

71.40% |

|

Physical |

31.60% |

18.80% |

14.70% |

1.41% |

0.38% |

67.00% |

Table 4 Summary of key bypass tunnel parameters in the prototype scale

|

|

Bypass tunnel |

Power house |

Spillway & flood |

Perm. channel |

Shihmen intake |

Total passed |

Modified |

Field |

none |

34.00% |

24.30% |

2.71% |

0.62% |

61.60% |

Existing |

Physical Model |

30.30% |

22.60% |

2.42% |

0.52% |

55.90% |

|

Plan A |

Field |

36.20% |

26.10% |

14.10% |

2.09% |

0.49% |

79.00% |

Physical Model |

35.40% |

22.90% |

12.60% |

1.83% |

0.41% |

73.00% |

|

Plan C |

Field |

32.90% |

28.20% |

17.70% |

2.25% |

0.53% |

81.80% |

|

Physical Model |

31.40% |

25.30% |

12.10% |

2.10% |

0.46% |

71.40% |

Table 5 Comparison of the percentage of sediments desilted through each outlet between the field scale and physical model scale cases

At Shihmen reservoir a combined field, physical model and numerical model study has been carried out. This paper focuses specifically on evaluating the turbidity current desilting processes using a 2D layer-averaged numerical model. The modified existing condition is simulated first which provides a baseline model for comparison with the bypass tunnel plans. Numerical results show that the model is capable of predicting the turbidity current movement characteristics in the reservoir. The predicted current movement speed and timing match well with the physical model data. The model also predicts well the sediment rates sluiced through all outlets. Next, two bypass tunnel plans (A and C) are simulated. The first set of model results are compared with the physical model results. It is shown that the model can predict the sediment rates through the bypass tunnels reasonably. The sediment desilting rate out of the reservoir is within 10% of the physical model data. The results lend further credence that the model is reliable in evaluating different desilting plans. The second set of modeling results confirm the finding of the physical model studies that the use of a sediment bypass tunnel (Plan A or C) may increase the total desilting rate of the reservoir close to 70% during a large typhoon event. The desilting rate increases more than 16% than the baseline modified existing scenario. Note that the sediment desilting rate predicted is for a high discharge and high sediment concentration event (typhoon Aere). The desilting rated may be smaller if smaller events occur. One reason is that the sediment fall velocity of the small to medium events may be larger than that at the high events due to flocculation. Larger fall velocity may lead to higher deposition in the reservoir and reduced desilting rates through the outlets. The numerical model is used to study the scale effect of the physical model. It shows that the physical model may under-predict the sediment rate sluiced through the outlets by about 10%.

The work reported in this paper was funded through a technical cooperation agreement by the Water Resources Agency (WRA) of Taiwan. The following engineers from WRA are acknowledged for their contributions in providing the needed data for the study: Ching-Hsien Wu, Tian-Yuan Shieh and Hung-Kwai Chen.

None.

©2018 La, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Water Day is celebrated globally on March 22nd. Water is the most essential source for sustaining

life, and it plays an important role in the well-being of every human being. From the International Journal of Hydrology, we wish to convey

to everyone the vital importance of water as a fundamental part of human life. To support this cause, we invites researchers to contribute

articles that highlight the importance of Water. To encourage participation, IJH is offering a 30% discount on all submissions received on

or before March 22nd.

World Water Day is celebrated globally on March 22nd. Water is the most essential source for sustaining

life, and it plays an important role in the well-being of every human being. From the International Journal of Hydrology, we wish to convey

to everyone the vital importance of water as a fundamental part of human life. To support this cause, we invites researchers to contribute

articles that highlight the importance of Water. To encourage participation, IJH is offering a 30% discount on all submissions received on

or before March 22nd.