International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 6

1Speech therapist, University Hospital Maria Aparecida Pedrossian UFMS, Master in collective health from UFMS, Brazil

2Speech therapist, Coordinator and teacher at CEFAC E Neuroqualis, Doctorate in neurology at UNIFESP, Brrazil

3Speech therapist, University Hospital Maria Aparecida Pedrossian UFMS, Language specialist at USC, Brazil

Correspondence: Giglio Vanessa P, Speech therapist, University Hospital Maria Aparecida Pedrossian UFMS, Master in collective health from UFMS, Brazil

Received: April 19, 2022 | Published: November 28, 2022

Citation: Vanessa GP, Adriana OL, Adriana DCL. Pre-hospitalization dysphagia and its relation with hospital length of stay. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2022;6(6):307-314. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2022.06.00296

Purpose: Motivated by the reports of difficulties in feeding experienced by patients before neurological impairment, this study sought to investigate whether the previous complaint of dysphagia of patients admitted to the stroke unit at Hospital Universitário Maria Aparecida Pedrossian - UFMS impacted the increase in hospital length of stay when compared to patients without a history and complaints of dysphagia before hospitalization.

Methods: This regards an observational, prospective, longitudinal, quantitative and qualitative field research. The sample included adult patients of both sexes, over 18 years old with or without complaints of dysphagia, who responded to the screening where data were collected indicating the presence or not of dysphagia before hospitalization. After speech therapy evaluation and establishment of the FOIS scale, patients were followed up until the moment of hospital discharge.

Results: Oropharyngeal dysphagia (DOF) was identified in 80% of the patients evaluated in this study. There was a significant association between not having a DOF and the absence of a previous complaint, as well as not having a DOF and an initial NIHSS score of less than 10 points. There was no association between length of hospital stay and the presence or absence of a previous DOF complaint.

Conclusion: It is concluded that the investigation of the previous complaint of dysphagia in patients affected by Stroke can provide guiding data to support the speech therapist during the functional evaluation of swallowing, however, in isolation, it does not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between presenting a previous complaint and the length of hospital stay.

Keywords: deglutition disorders, stroke, length of stay

Speech therapy in the hospital environment has gained more and more space for the recovery of patients affected by chronic diseases with alterations in swallowing.1 Being the speech therapist, the professional able to assess swallowing early and establish the safest feeding route, esteems The presence of this professional in the hospital environment can represent not only the reduction of risks associated with dysphagia, but also the costs involved in a prolonged hospitalization. Dysphagia is defined as any difficulty in swallowing resulting from an acute or progressive process that interferes with the transport of the bolus from the mouth to the stomach2–3 and results in loss of functionality and independence to feed.4 It is not considered as a disease, but as a symptom of a disease or the consequence of a surgical intervention, which can lead to serious complications, such as dehydration, malnutrition, aspiration of food and even death.5 Complications associated with aspiration are common in patients with dysphagia and can lead to severe pulmonary impairment, increasing morbidity, length of hospital stay, costs involved and the risk of death in these patients.6 Swallowing disorders were recognized by the WHO as a disability associated with increased morbidity, mortality and costs of necessary care. With the increase in survival rates and the aging of the population, swallowing disorders and the consequent pulmonary and nutritional complications have become an extremely important factor in the context of public health.7 Studies show that dysphagia has a significant impact on the length of hospital stay and is an indicator of poor prognosis, and early recognition of dysphagia and intervention in hospitalized patients is recommended to reduce morbidity and length of hospital stay.8 To this end, the use of systematic dysphagia screening can result in a significant decrease in cases of aspiration pneumonia and an improvement in the general condition of the patient.9

Dysphagia can be due to several etiological factors, being neurogenic dysphagia after Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA) quite common in the hospital environment that assists the Stroke Care Line in the Urgent and Emergency Care Network in the SUS. The presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia is considered one of the main sequelae observed after stroke, with a frequency that varies between 30 and 80%.10 This large variation described in most studies is probably related to the presence of heterogeneous samples and different methods of investigation of oropharyngeal swallowing.11,12 The speech therapy experience with these patients has shown that, often, the patient affected by post-stroke dysphagia presents complaints related to food prior to hospitalization and that, for different reasons, are not investigated or are underdiagnosed, but represent an aggravating factor in patients. with neurogenic dysphagia, which may be related to the severity of the disorder and the length of hospital stay. Considering the complexity of care that the patient diagnosed with stroke requires, other factors can also determine the increase in hospitalization time, such as pre-existing comorbidities, social conditions, difficulties in accessing complementary exams necessary for the outcome of the treatment and/or worsening. of the neurological picture.

Motivated by reports of feeding difficulties experienced by patients before neurological involvement, this study sought to investigate whether the previous complaint of dysphagia of patients admitted to the Stroke Unit of the Hospital Universitário Maria Aparecida Pedrossian - UFMS had an impact on the increase in length of stay when compared to patients with no history and complaint of dysphagia before admission to the hospital.

The present study is an observational, prospective, longitudinal, quantitative and qualitative field research that was carried out during the period of two consecutive months at the Maria Aparecida Pedrossian University Hospital, of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul in Campo Grande/ MS. The subjects included in this study were adult patients of both sexes, over 18 years of age with or without dysphagia complaints, in a state of alert (responding to simple commands) and in stable clinical conditions, admitted to the Cerebral Vascular Accident Unit (UAVC) from the Maria Aparecida Pedrossian University Hospital. The study was previously authorized by the Head of the Urgency and Emergency Unit, the sector responsible for the admission of patients to the Stroke Unit of Humap-UFMS, considering the lack of additional budgetary costs to the hospital institution (Annex 1).

After approval by the Research Ethics Committee under opinion number CAAE:33637120.1.0000.5161,the researchers followed the speech therapy routine adopted at the institution, with the speech therapy assessment performed within 24 hours after admission to the Stroke Unit and after the medical evaluation with the establishment of the neurological diagnosis. Subjects in a state of disorientation and/or with low cognitive level (Glasgow scale below 9),13 with clinical instability, as well as patients using tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation, patients with orotracheal intubation and patients in respiratory isolation were excluded from this study. To carry out this research, basic materials such as forms, clipboard, pen, computer, cup, plate, spoon and specific materials were used, such as: tongue depressor, flashlight, oximeter, personal protective equipment, foods of different consistencies and stethoscope.

After the presentation of the Free and Informed Consent Term (Annex 2), the patients and/or companions answered the previous information collection form, here called by the researchers as “Risk screening for dysphagia” (Annex 3) where the complaints related to the presence of dysphagia before hospital admission. The screening questionnaire was applied at the bedside, addressing 12 open questions related to the swallowing of foods of different consistencies and about the possible consequences of dysphagia, raising data indicative of the presence or absence of dysphagia before hospitalization.14 After screening, the patient was evaluated following the items of the Preliminary Assessment Protocol 9 adapted (PAP adapted by the researchers - Annex 4), which indicated the presence or absence of dysphagia, allowing the establishment of the level of oral intake according to the scale. FOIS - Functional Oral Intake Scale (Annex 5).15–17 Through the application of the adapted Preliminary Assessment Protocol (adapted PAP), aspects related to breathing, speech, voice, orofacial and cervical structures were evaluated. An evaluation was carried out regarding mobility, tonicity, sensitivity and coordination of the organs of the stomatognathic system, since the inadequacies of this musculature can negatively impact the functions of chewing and swallowing. The entire assessment was performed in bed, with the patient sitting, alert, with the head of the bed elevated to 45 degrees or more, according to the possibility of each case and the absence of medical contraindications. Data related to vital signs such as heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO2), as well as level of consciousness, feeding path, communication, voice, breathing, oxygen dependence.

The functional assessment of swallowing was performed by offering foods of different consistencies orally, starting with the thickened semi-liquid consistency, moving on to the consistency of thin liquids and, finally, offering solids. For the offer of food orally, the patient's performance in each consistency, the safety of the offer and the reported complaints about satiety or fatigue were considered. The foods used were: thickened orange diet juice, water and cornstarch biscuits, as they are foods available in the routine of this hospital, without the need for special preparations and/or previous requests to the nutrition sector. For thin liquid (LF) consistencies, 4 offers were made in the glass, namely: 2 ml, 3 ml, 5 ml and free sip. For the thickened semi-liquid (SLE) consistency, 3 measures were used: spoon “honeydew”, shallow spoon (5 ml) and full spoon (10 ml). For solid consistency, free-supply wafer was used. From the data collected in the evaluation and, after determining the presence of dysphagia, the patients were followed up by the speech therapy service of the Humap-UFMS, from Monday to Friday, in the morning, following the clinical and speech therapy evolution until the moment of hospital discharge, with the comparative record of evolution regarding swallowing through the FOIS scale. The FOIS scale is an instrument that makes it possible to evaluate the effectiveness of speech therapy in the rehabilitation of the oral route and was used as a marker of the safe progression of the oral diet through its registration at admission and at speech-language pathology and/or hospital discharge after speech-language pathology intervention of according to graduation levels from 01 to 07. For the speech therapy follow-up, facilitating strategies were used that involved tactile, thermal and gustatory stimulation, oromiofunctional exercises, swallowing maneuvers, airway protection maneuvers and postural adjustments that facilitate swallowing, in addition to guidance to patients and caregivers regarding the modulation of consistency, control of the volume of the food and the rhythm of food supply. All the data collected were tabulated for further statistical analysis, which made it possible to correlate the information obtained in each intervention phase, from the screening, following the evaluation and at the time of hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented in absolute and relative frequency, numerical data expressed as mean ± standard deviation,arranged in graph and table. Associations between variables were calculated by Fisher's Exact Test (2 x 2 tables) or by Chi-square test with Bonferroni correction for analysis of association between more variables. THECorrelation between length of hospital stay (days) and FOIS evolution was calculated using Spearman's Linear Correlation Test. It was considered asignificance level of 5% and tests carried out through the EPI INFO programTMversion 7.2.2.6.

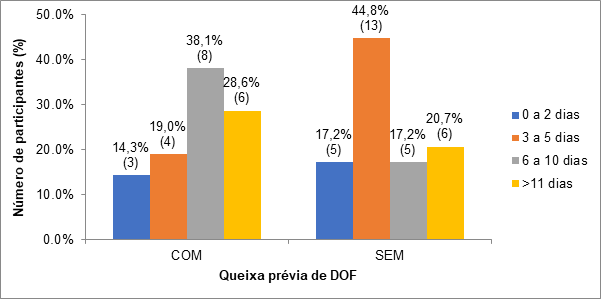

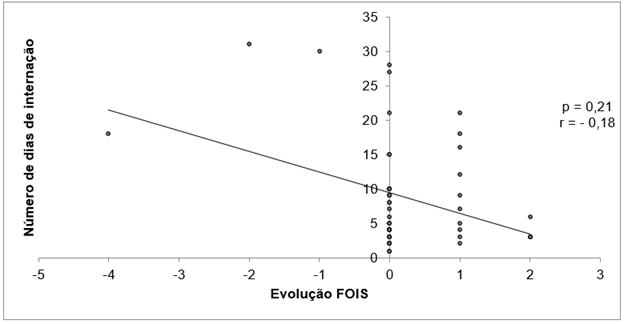

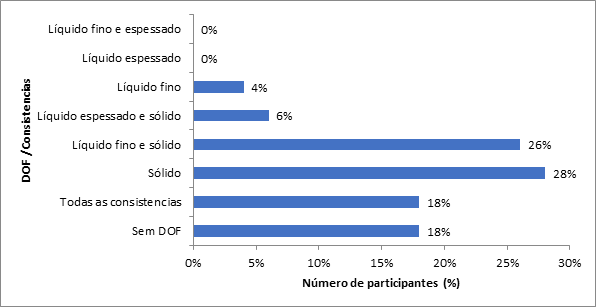

Data collection showed that 100% of the evaluated patients received a medical diagnosis of Ischemic Stroke, of which 34% underwent thrombolysis and 66% were admitted outside the therapeutic window to start treatment with fibrinolytic drugs or with risk factors that determined a contraindication for this type of treatment. The age of the participants ranged between 30 and 96 years, with a mean of 68.62 years with a standard deviation of 13.43 years, being 28 (56%) male and 22 (44%) female. Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OFP) was identified in 80% (n=40) of the patients evaluated in this study. There was a significant association between not having an OPD and the absence of a previous complaint (p=0.03), as well as not having an OPD and an initial NIHSS score of less than 10 points (p=0.007). DOF was not associated with age group (p=0.20), initial or final FOIS score (p=0.33 and p=1.00, respectively) or final NIHSS score (p=0.47) (Table 1). The initial or final FOIS scores were not associated with the age group of the participants (p=0.39 and p=0.30, respectively), as well as they were not related to the presence or absence of previous complaints (p=0.68 and p=0.30, respectively). =1.00, respectively) (Table 2). However, there was a significant association between an initial and final FOIS score >4 and an initial NIHSS score of less than 10 points (p=0.004 rp=0.02; respectively) (Table 2). There was no association between the length of hospital stay and the presence or absence of a previous complaint of OFP (p=0.19) (Figure 1). Despite showing a negative correlation between length of stay (days) and evolution of FOIS, that is, the shorter the length of stay, the greater the evolution of FOIS, this was not statistically significant (p=0.21; r=- 0.18) (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the consistencies related to DOF.

Variables |

Total(50) |

DOF |

p value |

|

No (10) |

Yes (40) |

|||

Age group |

||||

30 to 59 |

20.0 (10) |

40.0 (4) |

15.0 (6) |

0.20a |

60 to 79 |

62.0 (31) |

50.0 (5) |

65.0 (26) |

|

≥ 80 |

18.0 (9) |

10.0 (1) |

20.0 (8) |

|

Prior complaint |

||||

with complaint |

42.0 (21) |

10.0 (1) |

50.0 (20) |

0.03b |

no complaint |

58.0 (29) |

90.0 (9)A |

50.0 (20)B |

|

Initial FOIS |

||||

1 to 3 |

12.0 (6) |

0.0 (0) |

15.0 (6) |

0.33b |

≥ 4 |

88.0 (44) |

100.0 (10) |

85.0 (34) |

|

final FOIS |

||||

1 to 3 |

14.0 (7) |

10.0 (1) |

15.0 (6) |

1.00b |

≥ 4 |

86.0 (43) |

90.0 (9) |

85.0 (34) |

|

Initial NIHSS |

||||

0 to 9 |

56.0 (28) |

100.0 (10)A |

45.0 (18)B |

0.007a |

10 to 19 |

36.0 (18) |

0.0 (0) |

45.0 (18) |

|

≥ 20 |

8.0 (4) |

0.0 (0) |

10.0 (4) |

|

Final NIHSS |

||||

0 to 9 |

84.0 (42) |

100.0 (10) |

80.0 (32) |

0.47a |

10 to 19 |

8.0 (4) |

0.0 (0) |

10.0 (4) |

|

≥ 20 |

2.0 (1) |

0.0 (0) |

2.5 (1) |

|

No information |

6.0 (3) |

0.0 (0) |

7.5 (3) |

|

Table 1 Frequency distribution of the 50 patients to the association oforopharyngeal dysfunction in relation to the other clinical variables evaluated. Campo Grande, 2020

Note: Data presented as relative frequency (absolute frequency).Thechi-square test with Bonferroni correction; b Fisher's exact test. Capital letters in the lines point out the differences between the groups.

Variables |

initial FOIS |

p value |

final FOIS |

p value |

||

|

1 to 3 (6) |

>4 (44) |

|

1 to 3 (7) |

>4 (43) |

|

Age group |

||||||

30 to 59 |

0.0 (0) |

22.7 (10) |

039a |

0.0 (0) |

23.3 (10) |

0.30a |

60 to 79 |

83.3 (5) |

59.1 (26) |

85.7 (6) |

58.1 (25) |

||

≥80 |

16.7 (1) |

18.2 (8) |

14.3 (1) |

18.6 (8) |

||

Prior complaint |

||||||

with complaint |

33.3 (2) |

43.2(19) |

1.00b |

28.6 (2) |

44.2 (19) |

0.68b |

no complaint |

66.7 (4) |

56.8 (25) |

71.4 (5) |

55.8 (24) |

||

Initial NIHSS |

||||||

0 to 9 |

0.0 (0)B |

63.4 (28)A |

0.004b |

14.3 (1)B |

62.8 (27)A |

0.02b |

10 to 19 |

66.7 (4) |

31.8 (14) |

57.1 (4) |

32.6 (14) |

||

≥20 |

33.3 (2) |

4.5 (2) |

28.6 (2) |

4.7 (2) |

||

Table 2 Scores obtained in standardized assessmentsFOIS in relation to the other clinical variables evaluated in the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020

Note: Data presented as relative frequency (absolute frequency). VFOIS alues presented in points. chi-square attestation with Bonferroni correction; Fisher's exact test

Figure 1 Representation of the association between length of stay (days) and the presence or absence of a previous complaint of OFPin the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020.

Note: Chi-square test (p=0.19)

Figure 2 Representation of the correlation between the length of stay and the evolution of FOISin the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020.

Spearman's Linear Correlation Test

Figure 3 Representation of the prevalence of DOF according to the different consistenciesin the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020

Changes in cheek strength and rest were more prevalent among patients with OFP (p=0.0007 and p=0.03; respectively). Changes in the lips in relation to strength (p=0.01), mobility (p=0.0003) and rest (p=0.008) were also more associated with patients with OFP, as well as in relation to tongue strength (p=0.008). =0.03). Other structural alterations showed no association between the presence or absence of OFP (p>0.05), as detailed in Table 3. During the functional speech-language pathology assessment, a significant association was identified between the presence of OPD and inefficient oral uptake (p=0.04), extraoral escape (p=0.01), slowed oral transit (p<0.0001), mastication ineffective (p<0.0001) and presence of oral residue (p=0.003). No significant associations were identified between the other items evaluated and the DOF (p>0.05). The values are detailed in Table 4.

Structural Speech-Language Pathology Assessment |

DOF |

Value of P |

|

|

No (10) |

Yes (40) |

|

Cheek |

|||

changed strength |

20.0 (2)B |

80.0 (32)A |

0.0007b |

altered mobility |

20.0 (2) |

65.0 (26) |

0.014b |

altered rest |

30.0 (3)B |

70.0 (28)A |

0.03b |

altered sensitivity |

10.0 (1) |

15.0 (6) |

1.00b |

Lips |

|||

changed strength |

20.0 (2)B |

67.5 (27)A |

0.01b |

altered mobility |

20.0 (2)B |

82.5 (33)A |

0.0003b |

altered rest |

0.0 (0)B |

47.5 (19)A |

0.008b |

altered sensitivity |

20.0 (2) |

17.5 (7) |

1.00b |

Tongue |

|||

changed strength |

20.0 (2)B |

62.5 (25)A |

0.03b |

altered mobility |

20.0 (2) |

50.0 (20) |

0.15b |

altered rest |

0.0(0) |

0.0(0) |

- |

altered sensitivity |

10.0 (1) |

5.0 (2) |

0.49b |

GAG reflex present |

40.0 (4) |

60.0 (24) |

0.30b |

Altered saliva production |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

1.00b |

Vocal Quality Change |

10.0 (1) |

20.0 (8) |

0.67b |

Reduction of laryngeal elevation |

0.0 (0) |

17.5 (7) |

0.32b |

Dentition |

|||

complete |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

0.61a |

incomplete |

60.0 (6) |

67.5 (27) |

|

Absent |

40.0 (4) |

27.5 (11) |

|

Dental prosthesis |

70.0 (7) |

42.5 (17) |

0.16b |

Asymmetrical Face |

40.0 (4) |

75.0 (30) |

0.06b |

lack of communication |

0.0 (6) |

15.0 (6) |

0.33b |

Table 3 Changes identified in the structural speech-language pathology assessment of the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020

Note: Data presented as relative frequency (absolute frequency).Thechi-square test with Bonferroni correction; Fisher's exact test; (-) Statistical test not performed due to lack of observations in the category.

Functional speech-language assessment |

DOF |

Value of P |

|

|

No (10) |

Yes (40) |

|

Inefficient Oral Uptake |

0.0 (0) |

35.0 (14) |

0.04* |

food refusal |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

1 |

extraoral leak |

0.0 (0) |

42.5 (17) |

0.01* |

slowed oral transit |

0.0 (0) |

70.0 (28) |

<0.0001* |

ineffective chewing |

0.0 (0) |

95.0 (38) |

<0.0001* |

Presence Oral Residue |

0.0 (0) |

52.5 (21) |

0.003* |

Reduction of laryngeal elevation |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

1 |

presence of cough |

|||

Before |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

During |

0.0 (0) |

17.5 (7) |

0.32 |

After |

10.0 (1) |

20.0 (8) |

0.67 |

clear throat |

20.0 (2) |

22.5 (9) |

1 |

Cervical auscultation + |

0.0 (0) |

5.0 (2) |

1 |

Wet vocal quality |

0.0 (0) |

2.5 (1) |

1 |

dyspnea |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

Drop in O2 Saturation |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

Incomplete swallowing |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

Multiple Swallowing |

0.0 (0) |

30.0 (12) |

0.09 |

odynophagia |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

Table 4 Changes identified in the functional speech-language pathology assessment of the 50 patients. Campo Grande, 2020

Note: Data presented as relative frequency (absolute frequency).Thechi-square test with Bonferroni correction; Fisher's exact test; (-) Statistical test not performed due to lack of observations in the category.

There are several studies that have evaluated changes in swallowing biomechanics in post-stroke dysphagia individuals and the length of hospital stay, but the association of these changes and the presence of dysphagia complaints prior to hospitalization have been little reported. In the present study, of the total of 50 patients diagnosed with stroke, 100% had ischemic stroke, confirming the prevalence demonstrated in previous studies with this population.18,19 56% were male and 44% were female, not differing from the literature regarding epidemiological data.4,20,21 Patients in this acute stroke population included 27 general comorbidities, however, as in other studies,22 acute medical complications were not included in our analysis due to lack of sufficient data on these variables. The literature points out that dysphagia is prominently associated with older ages. In the period from 2005 to 2006, we analyzedover 77 million hospital admissions nTheNational Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), of which 271,983 were associated with dysphagia. Of these, it was observed that the group ofpatients with75 years or older had a dysphagia rate of 0.73%, which corresponds to more than twice the national average for all other age groups in the country where the research was carried out 8. In the present study, however, it was not possible to relate the prevalence of dysphagia in the age groups compared. THEDespite the higher prevalence of patients between 60 and 79 years of age presenting oropharyngeal dysphagia (OFP), this age group was also prevalent in the group of patients without OFP. The slightly larger difference observed in this age group was not statistically significant, and this fact may be justified due to the sample size of the research. As of the 50 patients, 62% are between 60 and 79 years old, it would be necessary to have a prevalence of patients in the other age groups that would allow us to compare them to reach a significant difference. In agreement with studies that relate the presence of post-bird dysphagia, the presence of OFP was identified in 80% of the patients evaluated in this study.10,23

In acute stroke, the prevalence of dysphagia has been reported to be between 28 and 65%, a variation that may be related to differences in the form of dysphagia assessment, in the configuration and time of the test used.23 Other Brazilian studies also point to a variation between 48 and 91% in the frequency of post-stroke dysphagia and correlate with the use of different diagnostic protocols, in addition to performing swallowing assessment at different times and phases, which can be acute, subacute or chronic, showing a difference in the results found.12,19,24 The association between not having OFP and the absence of a previous complaint of dysphagia (p=0.03) was significant and confirms the hypothesis of these researchers regarding the importance of using instruments that can track the presence of symptoms indicative of dysphagia prior to hospitalization and that are often under-considered in the patient's anamnesis and history. There was a relationship between not having a DOF and not having a previous complaint, that is, a screening that makes it possible to identify the existence or not of a previous complaint of DOF can be considered as a simple, inexpensive and effective indicator. The results obtained show that most patients who did not have a previous complaint were not diagnosed with OFP. In this line of reasoning, we can say that presenting the prior complaint is not indicative of OF.

Taking into account that dysphagia may be associated with factors such as a decrease in quality of life, aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, malnutrition and social isolation, some clinical guidelines recommend that the use of instruments for the early identification of the risk of dysphagia represents an alternative. practical, low-cost and that accuses cases in which a more detailed evaluation becomes necessary.25–27 The possibility of inserting a screening that seeks to track the difficulties experienced by the patient during feeding prior to hospitalization after cerebrovascular involvement seems to have a positive effect and aggregator of information for the professional who will carry out the functional assessment of swallowing. For the clinical assessment of patients with neurological impairment, some scales can be used to establish the degree of impairment. The National Institutes of Health has developed a stroke severity scale called the NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) that haveevidence of clinically acceptable reliability and good applicability.28 It should be noted, however, that although it is a widely accepted scale that addresses the clinical assessment of several aspects related to neurological conditions, it does not include the assessment of swallowing.15,29,30 Research shows that patients with severe impairments (NIHSS≥16) predict a high probability of death or severe disability while a score≤ 6 can be a predictor of good recovery.29 In the present research hthere was a relationship between patients who did not present OFP and an initial NIHSS score lower than 10 points (p=0.007). Only 8 patients had an initial NIHSS≥16, while 19 patients scored≤ 6 and 23 patients with scores between 7 and 15. However, there was a significant association between an initial NIHSS score < 10 points and a FOIS score > 4 both at baseline and Final. No patient with NIHSS below 09 had a FOIS scale below 4, which excludes the need to indicate an alternative route. The determination of the level of initial oral intake established by the FOIS scale was≤ 3 in only 6 patients with NIHSS above 10. Of the 44 patients who had an initial FOIS > 4, we obtained 63.4% of subjects classified with NIHSS up to 9.

It cannot be said in the present study that FOIS was effective (or adequate) to indicate the presence of OFP. Statistically, there was no association between a poor score on the FOIS scale and the presence of DOF. On the contrary, all patients, regardless of whether they had OFP or not, received scores above 4 on the scale, corresponding to the possibility of allowing oral feeding, even with modulations and/or consistency restrictions. Of the 50 patients followed up,31–33 did not show progress on the initial (acute stroke state) and final (hospital discharge) FOIS scale. Level evolution on the scale was observed in 14 patients and 3 had clinical complications during hospitalization with regression of the score level. The presence of variables such as senescence, poor dental conditions and the presence of comorbidities may be associated with maintaining the initial level of the FOIS scale in many patients at hospital discharge. However, it should be noted that the moment of hospital discharge does not always coincide with the speech therapy discharge, nor does it exclude the need for continuity of rehabilitation.

Among allAmong the patients evaluated, 16% were discharged from hospital within two days, a fact that may be associated with low NIHSS scores, which correspond to patients with lower risks and sequelae resulting from stroke and scores equal to or above 4 on the FOIS scale that allows the release of oral feeding. However, when we added the patients with and without OFP, we observed that the length of stay varied from 3 to 5 days in 34%, from 6 to 10 days in 26% and over 11 days in 24%. We consider that the length of stay may be related to other variables, such asthe presence of comorbidities and clinical intercurrences in addition to the presence of OFP associated or not with the previous complaint. In a study on thecorrelation of dysphagia evolution and clinical recovery in ischemic stroke, all cross-overs of the NIHSS neurological assessment scales and theModified Rankin Scalewith the FOIS and Rosembek scales in the acute phase, after 30 and 90 days of stroke, they obtained a weak correlation.31

This study did not show a direct association between length of stay and the presence or absence of a previous complaint of OFP. It is possible to analyze this data more comprehensively if we consider that the patient in question was not hospitalized for dysphagia properly, which is a secondary issue to the main reason for hospitalization. On the other hand, if the presence of a previous complaint in post-stroke patients was not associated with the length of stay in the hospital unit, we can say, based on extensive literature, that the presence of OFP can lead not only to prolonged hospitalization but also in the occupation of beds, preventing turnover and generating more hospital costs. A review and meta-analysis study that addressed research conducted in the United States, Europe and Asia observed an increase in hospital stay and costs with the oropharyngeal dysphagia patient group. Overall expenses measured via monetary cost increased by 40.36% in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia compared to their non-dysphagic counterparts.32 Study by Patel et al.33 who evaluated the economic impact of dysphagia of oropharyngeal and esophageal origin, revealed a 42% increase in hospitalization costs, despite differences in population, underlying condition, year or country of origin of the studies.

Similarly, the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia added between two and eight extra days to hospital stay, regardless of the reason for admission.33 36% in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia compared to their non-dysphagic counterparts.32 Study by Patel et al.33 who evaluated the economic impact of dysphagia of oropharyngeal and esophageal origin, revealed a 42% increase in hospitalization costs, despite differences in population, underlying condition, year or country of origin of the studies. Similarly, the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia added between two and eight extra days to hospital stay, regardless of the reason for admission 33. 36% in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia compared to their non-dysphagic counterparts.32 Study by Patel et al.33 who evaluated the economic impact of dysphagia of oropharyngeal and esophageal origin, revealed a 42% increase in hospitalization costs, despite differences in population, underlying condition, year or country of origin of the studies. Similarly, the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia added between two and eight extra days to hospital stay, regardless of the reason for admission.33

Often the terminologies dysphagia and bronchoaspiration are mistakenly used in a similar way, given the proven relationship between them, the similarity of circumstances in which they are involved and the negative impact that can be determined when the dysphagic patient also presents the risk of laryngotracheal aspiration of saliva and/or food. However, it is important to differentiate them according to what is evaluated and how the findings are interpreted. The approach among the subjects of this research considered dysphagia in its broad aspect, emphasizing the different phases of swallowing that ensure that food is carried out safely, with nutritional and affective gains, taking into account food safety and pleasure. We found that dental changes can impact the oral preparation process during mastication and the acceptance of certain consistencies, highlighting the solid consistency that requires the presence of satisfactory dental conditions and/or the presence of dental prostheses that guarantee that this phase of swallowing is performed. Effectively.34 We found a total of 50% of the patients evaluated with FOD for solid consistency associated with other consistencies and 28% with FOD only for solids, which totals 78% of patients with restriction to this consistency, which may be related to the chewing difficulty and poor dental conditions.

Data regarding dentition indicated that 95% of patients with OFP had incomplete or absent dentition, and of these, only 42, 5% used dental prostheses and 80% had ineffective chewing during the speech-language pathology assessment. This change justifies the difficulty presented with solid consistency and unchanged levels on the FOIS scale even with speech therapy, since modulations of food consistency were prescribed in order to guarantee oral intake without the possibility of evolution in the scale. Regarding the other evaluated consistencies, it should be noted that the presence of clinical signs of dysphagia with the consistency of thin liquid (48%) was present during its offer, while the consistency of thickened liquid seemed to provide greater security during the evaluation. In this study.

The use of the FOIS scale as an indicator of evolution carried out in a study with neurological and hospitalized patients revealed that 73.5% of the 49 patients showed progress in the level of the FOIS scale, indicating evolution in relation to swallowing functionality.16 However, similarly to the results found in the present study, Silvério et al.35 mention the research involving 3 different groups of patients with TBI, dementia and CVA, where most post-CVA patients remained at level 5 of the scale, with food of multiple consistencies, but requiring special preparation, until the end of the intervention. hospital speech therapy. The data observed in the present study regarding the maintenance of the same initial and final level on the FOIS scale may lead to new studies that correlate the changes typical of aging and dental conditions with an impact on chewing and swallowing in patients affected by stroke. According to Table 3 and 4, the results obtained demonstrate, respectively, the prevalence of alterations in terms of posture, sensitivity, strength and mobility of OFAs (phonoarticulatory organs) among patients with OFP, as well as the higher prevalence of functional alterations , such as inefficient oral uptake (p=0.04), extraoral leakage (p=0.01), slowed oral transit (p<0.0001), ineffective chewing (p<0.0001) and the presence oral residue after swallowing (p=0.003). In the sample of subjects surveyed by Carvalho et al.36 52.9% of the individuals presented alterations in the lip strength which, by generating an intraoral pressure deficit, causes disorganization of the bolus ejection.36 In addition to the decrease in intraoral pressure, the reduction in occlusion strength labial results in non-retention of liquid in the oral cavity and stasis of food in the vestibule, configuring impairment of stomatognathic functions.37

Considering the oral phase with its respective stages of preparation, qualification, organization and ejection,38 we highlight the existence of impairment of this phase in the findings of this research, as expressed in Table 4, highlighting the inefficient uptake of food with consequent extraoral leakage (or anterior) and the difficulty in the complete lip sealing due to the lack of morphofunctional integrity of the structures involved in the dynamics of swallowing. It is worth mentioning that the alterations found after the stroke are added to the structural alterations typical of the normal aging process, as this research addresses the elderly population. Although sensorimotor changes related to healthy aging can contribute to voluntary changes in food intake, the presence of age-related disease, including stroke, is the main factor that contributes to clinically significant dysphagia in the elderly. In addition to motor changes, age-related decreases in oral moisture, taste, and smell acuity may contribute to reduced swallowing performance in the elderly.39 The changes related to strength, mobility, sensitivity and tone of the structures of the lip, tongue and cheeks observed in the results expressed in Table 3 can compromise the functions of chewing and swallowing, generating changes in the intra-oral pressure mechanism and, consequently, in the other phases. of swallowing determining the presence of DOF. These findings corroborate the data found in the literature.38,40–42

Coughing is a reflex response of the brainstem that acts to protect the airway against the entry of foreign bodies. In the present study, the presence of cough was observed in 37.5% of patients with OFP, being more prevalent during (17.5%) and after (20%) swallowing. The presence of reflex cough during or after swallowing is considered a sign of aspiration due to oropharyngeal dysphagia, which may indicate the existence of sensitivity in the laryngeal region and the ability to expectorate, although it does not guarantee airway clearance.24 Swallowing alterations can be evaluated clinically or through an instrumental evaluation seeking to objectively elucidate data that confirm the clinical findings to determine the diagnosis. In this study, the structural and functional assessment performed by the speech therapists of the service was not supported by objective assessments, since these are not offered within the hospital institution where the research was carried out, a fact considered as a limitation of this study, making it impossible to correlate the findings. clinical trials with the occurrence of laryngotracheal penetration or aspiration. The presence of cough was observed in 37.5% of patients with OFP, being more prevalent during (17.5%) and after (20%) swallowing. Other changes found in this research, such as throat clearing, positive cervical auscultation, wet voice quality, dyspnea, drop in SpO2, incomplete swallowing, multiple swallowing and odynophagia, although commonly reported in the literature24,30,36,43–45 composing the conditions dysphagia, were not statistically significant in this study when compared to the group of patients without OFP.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Vanessa, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.