International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 4

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2Clinical research center, The Executive Administration of Research and Innovation, King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC) in Holy capital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Dr. Sharaf E. Sharaf, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, 1st floor, College of Pharmacy, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Western Region, Clinical Research administration, The Executive administration of Research and Innovation, King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC) in Holy Capital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia, Tel +966 532660411

Received: July 20, 2021 | Published: August 3, 2021

Citation: Sharaf SE, Al-shalabi BT, Althani GF, et al. Obesity self-management: knowledge, attitude, practice, and pharmaceutical use among healthy obese individuals in Saudi Arabia. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2021;5(4):110-121. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2021.05.00232

Introduction: Obesity is a chronic disease that is increasing in Saudi Arabia (SA) and globally. Obesity self-management among individuals is essential for managing obesity and its complications. This study aimed to conduct an obesity knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) assessment and prevalence of used pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications among individuals with obesity in SA.

Subjects and methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and April 2021. The participants completed a validated online administered questionnaire using the Survey Monkey website. Potential participants were approached in governmental hospitals, leisure centers, and shopping malls. The chi-square test was used to assess associations between categorical variables. In addition, correlations between the participants' KAP and outcome variables were measured using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r).

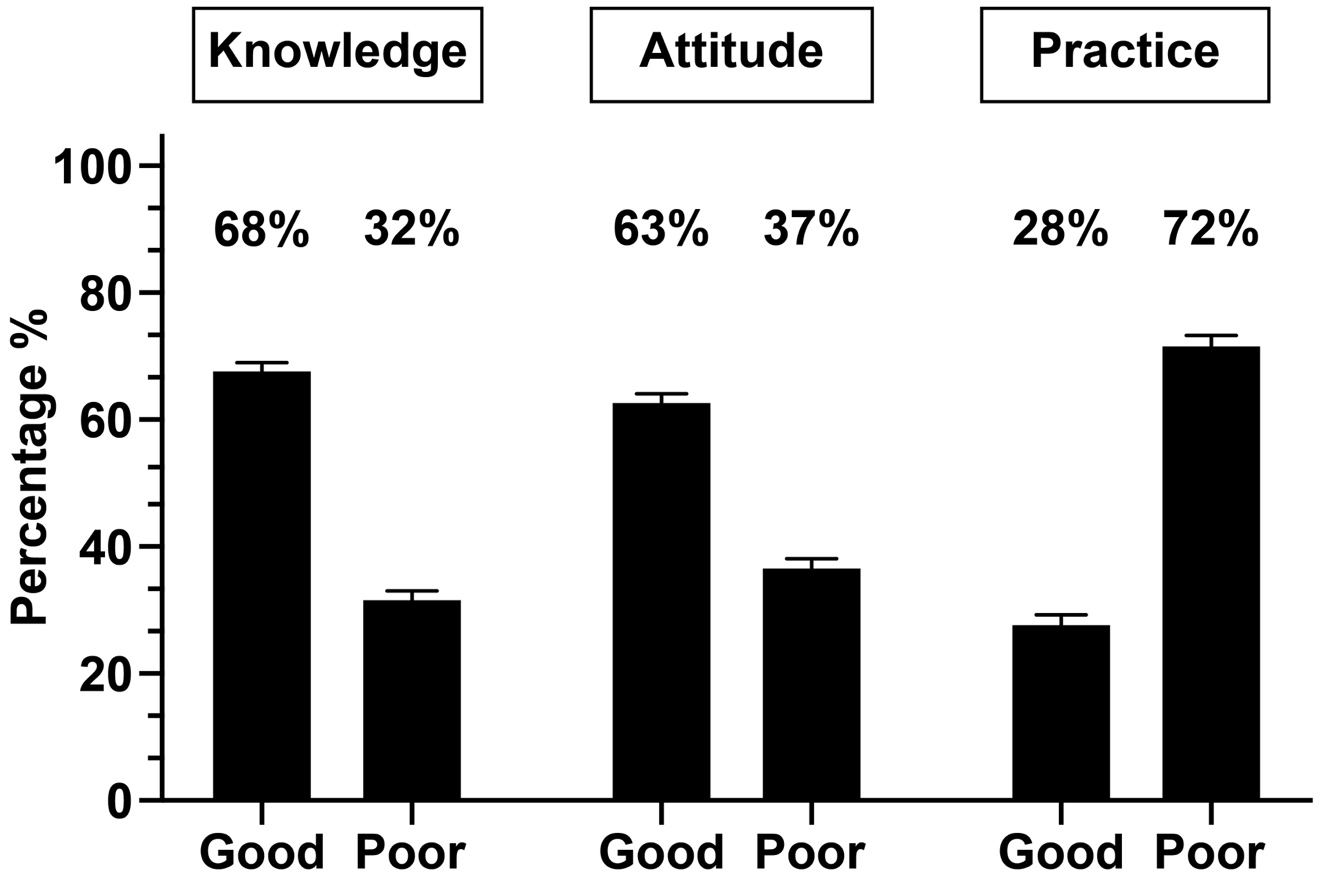

Results: In all, 410 obese individuals (mean age 40±14 years, range 18–80 years) were surveyed. Overall, 68% of participants reported good obesity knowledge, and 63% reported a good attitude, while 72% reported poor practice. In addition, there were significant positive linear correlations between knowledge and attitude (r=0.44, P<0.001), knowledge and practice (r=0.14, P<0.01), attitude and practice (r=0.11, P<0.05), body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference (WC) (r=0.25, P<0.01), while there were significant negative linear correlations between knowledge and BMI (r=−0.20, P<0.001), attitude and BMI (r=−0.19, P<0.001), practice and BMI (r=−0.67, P<0.001), knowledge and WC (r=−0.10, P<0.05), attitude and WC (r=−0.10, P<0.05), and practice and WC (r=−0.45, P<0.001). Interestingly, 67% of participants did not use any approved pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications due to a lack of anti-obesity treatment knowledge and safety.

Conclusion: The participants reported good knowledge and attitudes toward obesity, although these were not reflected in their practice levels. The lack of pharmaceutical knowledge, safety, and use of anti-obesity medications contributed directly to poor practice levels. Health authorities should establish clinical and pharmaceutical health education programs incorporating the latest pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications, including their applications and safety, for enhancing self-management and awareness among obese individuals.

Keywords: obesity, knowledge, attitude, practice, pharmaceutical use, Saudi Arabia, self-management, complications, anti-obesity

SA, Saudi Arabia; TAG, triacylglycerols; FFA, free fatty acids; IR, insulin resistance; MS, metabolic syndrome; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; CVD, cardiovascular disease; UAE, United Arab Emirates, WHO, World Health Organization, MOH, Ministry of Health

Obesity is one of the most common disorders worldwide, and its complications are significantly associated with increased disease and mortality rates.1,2 The main causes of non-genetic obesity are a sedentary lifestyle, increased food intake, and decreased physical activity.2 Obesity results from irregular and excessive fat accumulation in the adipose tissue, leading to an increase in both subcutaneous and visceral fat stores.1 Obesity-related dyslipidemia is primarily characterized by increased plasma free fatty acids (FFA) and triacylglycerols (TAG).3 Increased accumulation of TAG and FFA in the liver and muscles is highly associated with the development of insulin resistance (IR) and contributes to the development of metabolic syndrome (MS).4 MS is characterized by impaired hyperglycemia, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, leading to the development of atherogenic dyslipidemia and production of small dense LDL, which directly influences atherosclerosis.4,5 The continuous accumulation of FFA, increased TAG, decreased HDL, increased LDL, and impaired hyperglycemia control due to IR can result in obesity complications and progression of MS, thus increasing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension (HT), and cardiovascular disease (CVD).6

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity is increasing worldwide, and the Arabian Gulf (AG) countries, including Kuwait, Saudi Arabia (SA), United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain,7 have the highest obesity rates. SA is ranked second in terms of obesity rates.7 In the last few years, the incidence and prevalence of obesity in SA have increased among men and women of all age groups.8 In SA, the overall obesity and overweight rates are expected to rise from 2017 to 2022; the obesity rate may increase from 67.5 % to 77.6 % in women and from 38.2 % to 41.4 % in men.8,9 A recent study found that 28% of men and 44% of women in SA were overweight, while 66 % of men and 71 % of women were obese.9 Therefore, managing obesity in SA has become an important part of the Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines, which aim to establish a comprehensive guiding development program for clinicians, such as family medicine consultants and clinical pharmacists, to enhance the prevention, early diagnosis, and management of obesity.10

Obesity self-management, awareness, and pharmaceutical anti-obesity medication used use are considered essential treatment options and play significant roles in controlling obesity complications and reducing the risk of MS development.11,12 Obesity self-management and anti-obesity medication can be measured using knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) studies.13 Therefore, KAP is considered as an indicator for obesity awareness that is directly related to obesity self-management, and an increase or decrease in obesity KAP levels may directly affect obesity self-management.11 Although there are several studies on obesity worldwide,14-22 few have been published in SA until now, such as the study conducted by Alhawiti, 2021 in Medina, SA.23 Therefore, this study aimed to measure the pharmaceutical interventions and KAP of obesity among obese individuals in SA.

Ethical approval

This study received unconditional approval from the appropriate institutional review board (IRB) in KAMC with an approval number: 20-727.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using Slovin's formula, with a population size of approximately 4.5 million,24 confidence interval (CI) 0.95, and margin of error of 5%.25 Consequently, a sample size of 384 individuals was needed to achieve the required CI. To allow for potential dropouts, 410 participants were enrolled in this study after obtaining written informed consent.

Study design

This questionnaire-based cross-sectional study was conducted over a 4-month period between January and April 2021. Potential participants were randomly approached in outpatient clinics at local governmental and private hospitals, leisure centers, shopping centers, and recreational parks via a simple random sampling method. Well-trained and qualified senior pharmacy students were supervised and appointed for data collection after obtaining the necessary certification for conducting clinical research. The aims and objectives of the study were explained to the participants before obtaining their consent for participation in this study. The survey was self-developed to assess KAP and anti-obesity use after reviewing similar validated questionnaires from previously published studies, such as the study by Reethesh et al.,26 to fit this study's inclusion/exclusion criteria and the research scope.

Questionnaire

The survey was designed in English and then translated into Arabic, the local spoken language, by proficient speakers of both languages, and was subsequently revised to suit the general population. The correcting scheme for the KAP questions in each section was marked as one (1) point for a correct answer and zero (0) points for an incorrect answer, which was similar to previous KAP studies.27,28 The final score was calculated and divided into two main categories for each KAP section as follows:27,28

Good knowledge: If the participant obtained ≥80 % of the maximum possible knowledge question score. Poor knowledge: If the participant obtained <80 % of the maximum possible knowledge question score.27,28 Good attitude: If the participant obtained ≥80 % of the maximum possible score for the attitude questions. Poor Knowledge: If the participant obtained <80 % of the maximum possible score for the attitude questions.27,28 Good practice: If the participant obtained ≥80 % of the maximum possible score for the practice questions. Poor knowledge: If the participant obtained <80 % of the maximum possible score for the practice questions.27,28

A survey was designed to measure the participants' KAP regarding obesity, its complications, risk factors, management, and anti-obesity prevalence using an online survey development cloud-based software (Survey Monkey). The survey was presented online to the participants using electronic tablets (such as Apple iPad and Samsung Galaxy Tab) using the Survey Monkey website link. The survey was divided into six main parts: the first part included sociodemographic information, including gender, age, education level, and current employment. The second part included the participants' clinical history, diagnosis of obesity, and family history. The third to fifth sections contained questions about obesity KAP, respectively27 and comprised questions related to obesity-associated disease, risk factors, complications, and compliance. The final part concerning pharmaceutical anti-obesity use which addressed the prevalence of four main popular anti-obesity medications approved by the Saudi Food and Drug Agency (FDA): biguanides (i.e., Glucophage [metformin]-short-acting) 1,000 mg twice daily with meals; bile acid sequestrants (i.e., Formoline L112; active ingredients; ß-1,4-polymer of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) twice daily with meals; GLP-1 analogs (i.e., Liraglutide-Saxenda) 3 mg once daily before meals; and the lipase inhibitor orlistat 120 mg (i.e., Faltos or Xenical) three times daily before meals.

To validate the survey, a pilot study was conducted using 35 randomly selected obese individuals.27,28 While 20 participants were recruited from the KAMC, the remaining 15 were recruited from Heraa General Hospital. The participants provided voluntary informed consent. The corrected version of the questionnaire from the pilot study was presented to a committee of clinical professionals in the field within the CRA at KAMC for final approval and opinion regarding the survey's clinical and pharmaceutical content. On measuring test-retest reliability, good reliability was achieved, and the final form of the survey was used to approach the participants of this study.

Study populations (inclusion/exclusion criteria)

The selection criteria included obese Saudi nationals living in the Makkah region (including Makkah city, which is the Muslim's Holy Capital according to the Islam religion) between the ages of 18 and 80 years. The participants were enrolled after confirming their obesity status by obtaining the body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) according to the MOH guidelines in SA: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and WC ≥ 92 cm for men and ≥ 82 cm for women.9,29-31 The exclusion criteria included non-Saudis, non-obese participants with BMI ≤ 29 kg/m2 and WC ≤ 90 cm for men and ≤ 80 cm for women, participants with an inability to consent, and participants with a medical background (all-health-related education). The collected data responses were stored on a secure server. Participants who provided incomplete responses were excluded.

Statistical analysis

The data were transferred from Survey Monkey's speared sheets to Microsoft Excel for coding and then transferred to GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3 (Department of Pharmacology at the University of California San Diego, USA) for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic variables, KAP and anti-obesity use. The chi-square test was used to detect significant differences between the participants' KAP responses and variables. Correlations between the participants' KAP responses and outcome variables were measured using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), which calculates the linear relationship between two variables. Statistical significance was set as a P≤0.05.

Sociodemographic variables and obesity measurements

A total of 430 surveys were collected, of which 20 were excluded as they were incomplete. The remaining 410 surveys were included in data analysis, providing a response rate of 95 %. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There were more male participants (58.8 %, n=240) than females (41.5 %, n=170), and more young participants aged 18–40 years (54.4 %, n=223) than those aged 41–80 years (45.6 %, n=187). More than half of the participants had received a university education (50.5 %, n=207), followed by high school education (35.6 %, n=146), while the remaining participants had not received any official education (13.9 %, n=57). The number of participants who were not working (53.4 %, n=219) was higher than that of the working participants (46.6 %, n=191). Almost half of the participants (49.8 %, n=204) were considered Class I obese (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2), while the remaining half were classified into Class II obese (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2; 26.3 %, n=108) and Class III obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2; 23.9 %, n=98). The number of participants with a family history of obesity (57.6 %, n=236) was higher than those without obese members in their families (42.4 %, n=174).

|

Variables |

n (%) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Male |

240 (58.5%) |

|

Female |

170 (41.5%) |

|

Age |

|

|

18–40 years |

223 (54.4%) |

|

41–80 years |

187 (45.6%) |

|

Education |

|

|

None |

57 (13.9%) |

|

High school |

146 (35.6%) |

|

University |

207 (50.5%) |

|

Employment |

|

|

Working |

191 (46.6%) |

|

Not working |

219 (53.4%) |

|

BMI |

|

|

Class I 30–34.9 |

204 (49.8%) |

|

Class II 35–39.9 |

108 (26.3%) |

|

Class III ≥40 |

98 (23.9%) |

|

Family history of obesity |

|

|

Yes |

236 (57.6%) |

|

No |

174 (42.4%) |

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants with obesity (n=410)

Data represent the number of participants and percentages. BMI, body mass index

Table 2 shows the obesity measurements (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of the study participants. The mean height and weight were 1.65 ± 0.2 m and 100 ± 21 kg, respectively. The mean total BMI was 36.8 ± 5.8 kg/m2, while the means of the BMI Class I, II, and III were 32.4 ± 1.3, 37.3 ± 1.6, and 45.2 ± 4 kg/m2, respectively. The mean WC was 118 ± 14 cm in male participants, 105 ± 14 cm in female participants, and 113.2 ± 15 cm in all participants.

|

Variables |

Mean ± SD |

|

Height |

1.65 ± 0.2 m |

|

Bodyweight |

100 ± 21 kg |

|

BMI Class I |

32.4 ± 1.3 kg/m2 |

|

BMI Class II |

37.3 ± 1.6 kg/m2 |

|

BMI Class III |

45.2 ± 4 kg/m2 |

|

Total BMI |

36.8 ± 5.8 kg/m2 |

|

WC (MP) |

118 ± 14 cm |

|

WC (FP) |

105 ± 14 cm |

|

WC (TP) |

113.2 ± 15 cm |

Table 2 Obesity measurements of obese individuals in this study (n=410)

BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; MP, male participants; FP, female participants; TP, total participants; SD, standard deviation

Obesity knowledge and awareness evaluation

Figure 1 displays the KAP of obesity measurements among obese individuals in this study. The participants demonstrated good knowledge of obesity as 68 % (n=280) of the participants responded correctly to the obesity knowledge assessment questions (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of obesity measurements among individuals with obesity.

The frequency distribution of obesity knowledge among obese individuals in this study is shown in Table 3. The definition of obesity was correctly reported by 85.4 % (n=350) of the study participants, and 95.1 % (n=390) knew that eating a diet rich in carbohydrates, fats, and sugars may contribute to obesity. However, the participants' demonstrated conflicting responses regarding consistent stress as a risk factor for obesity. Additionally, 90.2 % (n=370) of participants knew that maintaining good physical activity and a healthy diet can manage obesity. Furthermore, 71.5 % (n=293) of participants knew that smoking is a risk factor for obesity complications. Unexpectedly, 70 % (n=287) of participants did not know that there were approved anti-obesity medications that could enhance weight loss along with exercise and a healthy diet.

|

Knowledge Assessment |

Answers |

Count (n) |

Percent % |

|

Do you know about obesity? |

Yes |

350 |

85.4 |

|

No |

16 |

3.9 |

|

|

I don't know |

44 |

10.7 |

|

|

Eating a diet rich in carbohydrates, fats, and sugars can contribute to obesity? |

Yes |

390 |

95.1 |

|

No |

3 |

0.7 |

|

|

I don't know |

17 |

4.2 |

|

|

Consistent stress is a risk factor that contributes to obesity? |

Yes |

152 |

37 |

|

No |

148 |

36.2 |

|

|

I don't know |

110 |

26.8 |

|

|

Maintaining good physical activity & a healthy diet will manage obesity? |

Yes |

370 |

90.2 |

|

No |

32 |

7.8 |

|

|

I don't know |

8 |

2 |

|

|

Smoking is a risk factor that contributes to obesity complications? |

Yes |

293 |

71.5 |

|

No |

40 |

9.7 |

|

|

I don't know |

77 |

18.8 |

|

|

There are approved anti-obesity medications that could enhance weight loss along with exercise and a healthy diet? |

Yes |

75 |

18.3 |

|

No |

48 |

11.7 |

|

|

I don't know |

287 |

70 |

Table 3 Frequency distribution of obesity knowledge among obese individuals (n=410)

Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate the participants' awareness levels regarding the prolonged effects of obesity on major vital organs and obesity complications, respectively. The majority of the participants (90 %, n=369) were aware that obesity affects the heart, followed by the pancreas, with a response rate of 84 % (n=344). About half of the participants were aware of the effects of obesity on the pancreas (53 %, n=217) and liver (51 %, n=209). The lowest response rates were regarding the impact of obesity on the kidneys (40 %, n=164) and lungs (36 %, n=148). Moreover, a majority of participants demonstrated satisfactory awareness levels regarding obesity and related diseases as follows: 90 % (n=369) participants were aware that obesity is related to CVD, 87 % (n=357) indicated that obesity is related to T2DM, 85 % (n=349) were aware that obesity is related to arthritis, and 81 % (n=332) knew about the relationship with HT. Comparatively, the awareness levels were not adequate regarding the relationship between obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (57 %, n=234) and dyspnea (53 %, n=217).

Table 4 demonstrates the association between the knowledge questions and the participants' demographic variables. Participants with a university education provided the highest significant responses regarding knowledge of obesity (90 %, P=0.05) and the importance of maintaining physical activity and a healthy diet for obesity management (96 %, P=0.05) compared with participants with no education or high school education.

|

Knowledge questions |

Gender |

Age |

Educational background |

Employment |

Family history |

||||||

|

Male |

Female |

18–40 years |

41–80 years |

None |

High School |

University |

Working |

Not |

Yes |

No |

|

|

n=240 |

n=170 |

n=223 |

n=187 |

n=57 |

n=146 |

n=207 |

n=191 |

n=219 |

n=236 |

n=174 |

|

|

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

|

|

Do you know about obesity? |

85 |

86 |

65 |

86 |

75 |

65 |

90* |

86 |

86 |

88 |

82 |

|

Eating food rich in carbohydrates, fats, and sugars contributes to obesity? |

94 |

96 |

70 |

80 |

83 |

90 |

80 |

96 |

95 |

95 |

94 |

|

Consistent stress is a risk factor that contributes to obesity? |

30 |

25 |

50 |

40 |

34 |

40 |

20 |

41 |

32 |

45 |

35 |

|

Maintaining good physical activity & a healthy diet will manage obesity? |

89 |

92 |

70 |

80 |

50 |

60 |

96* |

92 |

90 |

90 |

91 |

|

Smoking is a risk factor that increases obesity complications? |

50 |

60 |

70 |

84 |

66 |

51 |

60 |

75 |

65 |

72 |

71 |

|

There are approved anti-obesity medications that can enhance weight loss along with exercise and a healthy diet? |

15 |

18 |

18 |

17 |

18 |

16 |

17 |

16 |

18 |

17 |

15 |

Table 4 Association between knowledge questions and participant's demographic variables

*: Significant difference on chi-square test (P£0.05)

Obesity attitude evaluation

As shown in Figure 1, the participants demonstrated good attitude levels (63 %, n=260) based on their responses. Table 5 shows the frequency distribution of obesity attitudes among obese individuals in this study. Most of the participants (71.7 %, n=294) disagreed that healthy individuals could consume healthy and unhealthy diets. A majority of the participants (85.6 %, n=351) disagreed that maintaining good physical activity can be stopped once an individual reaches a normal BMI, and a similar number of participants (87.8 %, n=360) disagreed that healthy diet consumption can be stopped once a normal BMI is reached. Furthermore, almost all participants (93.9%, n=385) agreed that obese individuals should know more about obesity self-management to reduce the risk of obesity complications. Remarkably, 65.9% (n=270) participants were unaware that anti-obesity medications could be as safe and effective as performing regular exercise and following a healthy diet for managing obesity.

|

Attitude Assessment |

Answers |

Count (n) |

Percent % |

|

Healthy individuals can consume healthy and unhealthy diets? |

Agree |

93 |

22.7 |

|

Disagree |

294 |

71.7 |

|

|

I don't know |

23 |

5.6 |

|

|

You can stop maintaining good physical activity once a normal BMI is reached. |

Agree |

50 |

12.2 |

|

Disagree |

351 |

85.6 |

|

|

I don't know |

9 |

2.2 |

|

|

Individuals with obesity should know more about obesity self-care management to reduce the risk of obesity complications. |

Agree |

385 |

93.9 |

|

Disagree |

10 |

2.4 |

|

|

I don't know |

15 |

3.7 |

|

|

Anti-obesity medications are not safe and are not as effective for obesity management as performing exercises and following a healthy diet. |

Agree |

58 |

14.1 |

|

Disagree |

82 |

20 |

|

|

I don't know |

270 |

65.9 |

|

|

You can stop consuming a healthy diet once a normal BMI is reached. |

Agree |

40 |

9.8 |

|

Disagree |

360 |

87.8 |

|

|

I don't know |

10 |

2.4 |

Table 5 Frequency distribution of attitude questions

BMI, body mass index

Table 6 demonstrates the association between the attitude questions and participants' demographic variables. Compared with participants with no education or high school education, participants with a university education provided the most significant responses regarding a negative attitude toward stopping physical activity once a normal BMI is reached (95 %, P=0.05), eliminating the consumption of a healthy diet once a normal BMI is reached (96 %, P=0.05), and anti-obesity medications being neither safe nor effective for managing obesity in comparison with exercising and following a healthy diet (19 %, P=0.05).

|

Attitude questions |

Gender |

Age |

Educational background |

Employment |

Family history |

||||||

|

Male |

Female |

18–40 years |

41–80 years |

None |

High School |

University |

Working |

Not |

Yes |

No |

|

|

n=240 |

n=170 |

n=223 |

n=187 |

n=57 |

n=146 |

n=207 |

n=191 |

n=219 |

n=236 |

n=174 |

|

|

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

|

|

Healthy individuals can consume healthy and unhealthy diets? |

65 |

70 |

80 |

90 |

65 |

52 |

50 |

75 |

70 |

70 |

60 |

|

You can stop maintaining good physical activity once a normal BMI is reached. |

80 |

75 |

85 |

75 |

80 |

72 |

95* |

88 |

85 |

88 |

82 |

|

Patients should know more about obesity self-care management? |

80 |

90 |

80 |

75 |

91 |

96 |

93 |

95 |

94 |

94 |

92 |

|

Anti-obesity medications are not safe and are not as effective for obesity management as performing exercises and following a healthy diet. |

18 |

20 |

18 |

19 |

7 |

6 |

19* |

15 |

17 |

19 |

18 |

|

You can stop maintaining a healthy diet once a normal BMI is reached. |

80 |

76 |

85 |

95 |

65 |

50 |

96* |

85 |

83 |

90 |

91 |

Table 6 Association between the attitude questions and participant's variables

*: Significant difference on chi-square test (P£0.05). BMI: body mass index

Obesity practice evaluation

As shown in Figure 1, the participants' practice responses were not as adequate as expected and reflected poor practice levels (72 %, n=297). Table 7 displays the frequency distribution of obesity attitudes among obese individuals in this study. More than half of the participants (59.5 %, n=244) consumed more than four cups of caffeinated drinks daily, in addition to tea and coffee. Moreover, 52 % (n=213) of participants did not perform any physical exercise to manage obesity, and 68.2 % (n=280) of participants did not use tobacco products, including electronic smoking. Furthermore, 53.7 % (n=220) of participants consumed more than five meals of unhealthy fast food enriched with carbohydrates and fats every week, while 64.7 % (n=265) claimed they adopted a healthy lifestyle to manage obesity. Surprisingly, 67.6 % (n=277) of participants did not take any FDA-approved anti-obesity medications.

|

Practice Assessment |

Answers |

Count (n) |

Percent % |

|

Do you drink too many caffeinated drinks, including tea and coffee (more than 4 cups a day)? |

Yes |

244 |

59.5 |

|

No |

150 |

36.6 |

|

|

I don't know |

16 |

3.9 |

|

|

Do you follow a current physical exercise regimen to manage obesity? |

Yes |

193 |

47 |

|

No |

213 |

52 |

|

|

I don't know |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Do you smoke or use any tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes? |

Yes |

122 |

29.8 |

|

No |

280 |

68.2 |

|

|

I don't know |

8 |

2 |

|

|

Do you consume a lot of unhealthy fast food enriched with carbohydrates and fats (more than 5 meals a week)? |

Yes |

220 |

53.7 |

|

No |

180 |

43.9 |

|

|

I don't know |

10 |

2.4 |

|

|

Have you adopted a healthy lifestyle to manage obesity? |

Yes |

265 |

64.7 |

|

No |

140 |

34.1 |

|

|

I don't know |

5 |

1.2 |

|

|

Do you take any FDA-approved anti-obesity medications for obesity management? |

Yes |

93 |

22.7 |

|

No |

277 |

67.6 |

|

|

I don't know |

40 |

9.7 |

Table 7 Frequency distribution of practice questions

FDA, food and drug administration

Table 8 shows the associations between the participants' demographic variables and practice questions. Working participants provided a significantly higher response to physical exercise for obesity management (65 %, P=0.05) than non-working participants. Additionally, participants without a family history of obesity provided a more significant response regarding unhealthy fast-food consumption comprising more than five meals per week (55%, P=0.05) than participants with a family history of obesity. Female participants provided a more significant response regarding adopting a healthy lifestyle to manage obesity (70 %, P=0.05) and intake of FDA-approved anti-obesity medications (21 %, P=0.05) than male participants.

Practice questions |

Gender |

Age |

Educational background |

Employment |

Family history |

||||||

Male n=240(%) |

Female n=170 (%) |

18–40 years n=223 (%) |

41–80 years n=187(%) |

None n=57 (%) |

High School n=146 (%) |

University n=207 (%) |

Working n=191(%) |

Not working n=219(%) |

Yes n=236(%) |

No n=174 (%) |

|

Do you drink too many caffeinated drinks, including tea |

37 |

45 |

80 |

75 |

38 |

40 |

51 |

35 |

45 |

39 |

42 |

Do you follow a current physical exercise regimen to |

48 |

42 |

75 |

85 |

49 |

45 |

40 |

65* |

45 |

43 |

50 |

Do you smoke or use any tobacco products, including |

64 |

70 |

85 |

95 |

68 |

71 |

80 |

68 |

75 |

69 |

75 |

Do you consume a lot of unhealthy fast food enriched with |

32 |

45 |

70 |

80 |

45 |

40 |

50 |

40 |

48 |

35 |

55* |

Have you adopted a healthy lifestyle to manage obesity? |

50 |

70* |

70 |

80 |

59 |

66 |

62 |

65 |

61 |

65 |

60 |

Do you take any FDA-approved anti-obesity medications |

5 |

21* |

18 |

20 |

17 |

16 |

19 |

18 |

17 |

19 |

15 |

Table 8 Association between practice questions and participant's demographic variables

*: Significant difference on Chi-square test (P-value 0.05). FDA: Food and Drug Administration

Correlation measurements

Table 9 shows that there was a significant positive linear correlation between knowledge and attitude (r=0.44, P<0.001), knowledge and practice (r=0.14, P<0.01), attitude and practice (r=0.11, P<0.05), and BMI and WC (r=0.25, P<0.01). Furthermore, there was a significant negative linear correlation between knowledge and BMI (r=−0.20, P<0.001), attitude and BMI (r=−0.19, P<0.001), practice and BMI (r=−0.67, P<0.001), knowledge and WC (r=−0.10, P<0.05), attitude and WC (r=−0.10, P<0.05), and practice and WC (r=−0.45, P<0.001).

|

Variables |

Pearson correlation coefficient (r) value |

P |

|

Knowledge vs. attitude |

0.44 |

£.1** |

|

Knowledge vs. practice |

0.14 |

£.1** |

|

Attitude vs. practice |

0.11 |

0.05* |

|

Knowledge vs. BMI |

−0.20 |

£.1** |

|

Attitude vs. BMI |

−0.19 |

£.1** |

|

Practice vs. BMI |

−0.67 |

£.1** |

|

Knowledge vs. WC |

−0.10 |

0.05* |

|

Attitude vs. WC |

−0.10 |

0.05* |

|

Practice vs. WC |

−0.45 |

£.1** |

|

BMI vs. WC |

0.25 |

£.1** |

Table 9 Correlations between KAP variables and obesity measurements

BMI, body mass index; KAP, knowledge, attitude, practice; WC, waist circumference *P£0.05 and **P£0.01

Used pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications

The prevalence of anti-obesity medication use by the participants is shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, 67 % (n=275) of participants did not use any anti-obesity medications. Only 10 % (n=41) of participants used Formoline L112 and metformin (Glucophage). Furthermore, 7 % (n=29) of participants used Orlistat-Faltos, and only 6 % (n=25) used the GLP-1 analog Liraglutide-Saxenda.

Increased obesity self-management and awareness among healthy individuals with obesity is important to reduce the risk of obesity complications and incidence of related diseases.11 Therefore, this study surveyed 410 healthy Saudi individuals aged 18–81 years with confirmed obesity based on their BMI and WC measurements to measure their current obesity self-management and awareness levels. High levels of obesity knowledge and attitude was detected among the participants of this study but also showed poor levels of obesity practice. Furthermore, the majority of the participants did not use any pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications neither followed physical exercise programmes for obesity management.

Although the participants had good knowledge and attitude levels, they demonstrated poor practice. Similar results were found in a study conducted by Laar et al.32 Alhawiti revealed similar obesity KAP results with satisfactory levels of knowledge but poor levels of attitude and practice.23 However, another study showed that poor levels of obesity knowledge reflected poor attitudes and practice levels.21

It has been shown that a higher education level enhances knowledge and attitude levels.23,33 Knowledge and attitude were also significantly associated with the practice; hence, improving knowledge and attitude will improve practice levels. Similar results were reported by Alhawiti.23 KAP levels were significantly associated with BMI and WC; therefore, improving KAP levels by improving BMI and WC measurements could reduce obesity.23 Laar et al.32 also found a significant correlation between knowledge and BMI.32 Similarly, Saleh et al. demonstrated that practice levels were significantly associated with BMI.33 Therefore, good levels of obesity knowledge may result in good practice levels; however, several factors can influence the practice levels despite the presence of good obesity knowledge levels, which can be modifiable (pharmaceutical intervention, drug compliance, time management, self-efficacy, physical exercise, BMI, WC, and psychological factors such as motivation and depression) or non-modifiable (sex, age, and race).

A key finding of this study is that more than half of the participants did not use any approved pharmaceutical anti-obesity medications and did not follow a physical exercise program. This may be explained by their lack of anti-obesity medication knowledge and safety, which was reflected by their low responses to the anti-obesity questions. Therefore, the lack of anti-obesity medication use among the participants was strongly associated with poor practice levels. However, anti-obesity medication use can improve the patient's practice levels by promoting weight loss, which improves the BMI and WC, and contributes to obesity management. Therefore, the administration of the Saudi FDA-approved anti-obesity medication such as Liraglutide-Saxenda is highly recommended as it is safe and easy to use and promotes weight loss by controlling and reducing the appetite, which may improve the participants' practice levels.34

Furthermore, many approved types of exercise can improve fitness levels and promote weight loss. According to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), an individual needs 150–250 min/week of moderate-intensity physical activity for modest weight-loss, and more than 250 min/week of moderate-to-high intensity exercise to lose a significant amount of weight.35 Pharmaceutical and physical exercise interventions along with a suitable healthy diet can enhance caloric expenditure and reduce caloric intake, which promotes weight loss and better fitness levels.

Therefore, it is vital for health authorities to implement updated health education programs for obesity comprising anti-obesity medications, physical exercises, and suitable healthy diets to enhance obesity KAP levels and promote obesity anti-obesity applications. The identified weak points in the obesity KAP survey in this study and other similar studies in SA23 can help clinical pharmacists and clinicians to compose a comprehensive education program that addresses these weak areas and illustrates the importance of obesity self-management. Furthermore, our results can aid in constituting a comprehensive clinical and pharmaceutical health education program for health providers and individuals with obesity. This program should include the applications and safety of the latest anti-obesity medications, latest approved physical exercises, and potential diet and caloric intake plan to enhance their knowledge and awareness for the optimal management of obesity, along with reducing the risk of complications and incidence of related diseases.

The study was conducted in the Makkah region of SA; therefore, the results may not reflect the general population of SA. Additionally, the sample size was not representative of the studied region. The total population of the Makkah region is estimated to be more than 4.5 million people;18 however, it can still be considered a statistically representative random sample. Furthermore, the use of only four major classes of anti-obesity medications was measured, while the use of other anti-obesity medications and natural (herbal) products that could affect obesity management by causing weight loss was not measured.

This study shows that Saudi individuals with obesity have good knowledge and attitude levels toward obesity; however, this is not reflected in their practice levels. Significant positive correlations between KAP variables were detected, and significant negative correlations between KAP variables and obesity measurements were also observed. Consequently, enhancing knowledge and attitude levels can influence practice levels and reduce BMI and WC. A key finding was that more than half of the participants did not use any FDA-approved anti-obesity medications for obesity management, which significantly contributed to reduced practice levels. Therefore, health authorities must direct clinical pharmacists and clinicians to compose a clinical and pharmaceutical health education program illustrating the applications and safety of the latest anti-obesity medications.

Dr Sharaf E. Sharaf was responsible for the study’s concepts, clinical design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data acquisition and direct supervising of data collectors, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, manuscript review and final approval of the manuscript.

The author would like to give special thanks to the dedicated senior pharmacy students who helped in clinical research and data collection, which contributed to the successful completion of this study: Ms. Bushra T. Al-Shalabi, Ms. Ghada F. Althani, Mr. Hassan M. Bazuhair, Mr. Bashir J. Fairaq, Mr. Faris A. Ali, Mr. Abdulrahman M. Almontshri, and Mr. Farraj M. Aloqla. Special thanks to KAMC for approving and supporting this observational study, and facilitating data collection from potential participants in the Makkah region health clusters. Many thanks to the medical staff of the governmental hospitals in the health clusters and sales managers in the Makkah region's leisure centers and shopping malls for their endless help and support during the data collection period. Many thanks to all participants who voluntarily completed the survey in this study.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2021 Sharaf, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.