International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Opinion Volume 7 Issue 5

Department of Neurology, Gaffrée and Guinle University Hospital, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Correspondence: Mariana Ribeiro Pereira, Department of Neurology, Gaffrée and Guinle University Hospital, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Maracanã, Mariz e Barros, 775. Gaffree and Guinle University Hospital, postal code 20270-004, Brazil

Received: July 20, 2023 | Published: September 13, 2023

Citation: Pereira MR. Illness and The Stories We Tell Ourselves. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2023;7(5):160-161. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2023.07.00332

Most essential therapies for neurological patients do not come from a medical prescription but from appropriate referrals and follow-ups with other professionals. Medications often serve as crutches. In this context, a physician tells readers how literature helped her better understand patients by reading what writers had to say about what disease is and what it means to be ill.

Keywords: literature, medicine and literature, neurology and literature

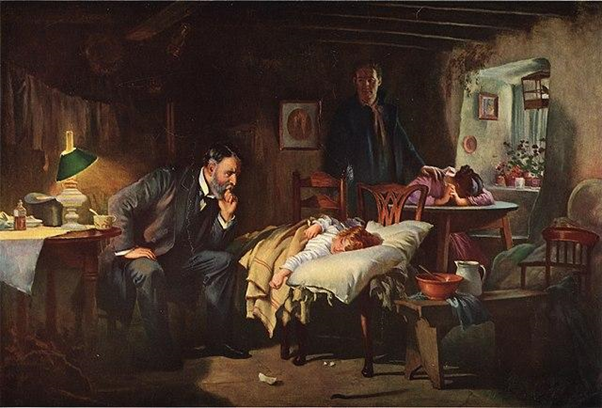

It feels like time has shortened over the past two years. After starting my medical residency, among the things that have changed, there has been little time left for reading. Non-medical literature became secondary to a cycle of "poor sleep - rush to residency - study." But, in the middle of this cycle, as a future neurologist, I understood how seldom a doctor can change the course of a patient's history. Most essential therapies do not come from a medical prescription but from appropriate referrals and follow-ups with other professionals, such as physiotherapists, speech therapists, psychologists, and nutritionists. Medications often serve as crutches. In this context, I rediscovered the format of reading that fits into my life as a physician. To better understand my patients, I wanted to learn what writers I already liked had to say about what disease is and what it means to be ill (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Reproduction of Luke Fildes' painting The Doctor, by Joseph Tomanek, 1933 (from Wikimedia Commons).

The importance of naming

In January 1930, Virginia Woolf (Figure 2) published "On Being Ill". In this book, Woolf expresses her disappointment with the lack of words to describe illness. Furthermore, she shows how little space has been dedicated to disease in non-medical literature. According to Woolf, we need a new vocabulary that extends to the limits of what illness can cause to the body. We also need a "new hierarchy of passions" regarding what should be primary in a novel: "Love should be deposed in favor of a forty-degree fever; jealousy should give way to sciatic pain; insomnia should take on the role of the villain...".1

Naming and describing symptoms is crucial. In addition to a specific vocabulary, explaining the names given during a consultation is necessary. Explain, as far as possible, what the patient feels and what, among all the signs, can be attributed to the disease and what belongs to the patient himself; explain, as far as we know, how things may have started.

The metaphors of illness

When we put the words in the center, it also becomes vital to help our patients to express their doubts. This year, I cared for a mother of two autistic children who wanted to understand: "Is their illness my fault?". Annie Ernaux wrote, in 1952, recalling her life as a twelve years old, that "disease was confusingly stained by error, like an individual's carelessness regarding their own destiny".2 In "Illness as Metaphor", Susan Sontag wrote about tuberculosis's role in people's minds in the nineteenth century - it was the disease of passionate artists and young people. Sontag then compares the myths around tuberculosis with the ideas most people created about cancer, the disease that started to hound minds over the twentieth century. Opposite to tuberculosis, cancer was a punishment for terrible people who committed mistakes that did not fit the specter of love.3

Ernaux and Sontag helped me understand that illness often comes with an association with a particular situation or personal characteristic that projects the etiology of the disease onto the individual. The etiological and pathophysiological substrates are lost, giving way to guilt as the source of a disorder.

I explained to that mother the likelihood of her children's autism having a genetic cause. After discussing this, she confided in me details of her personal life that made her wonder about the association of the disease with herself. She said talking was important for her to reflect on what the "feeling of guilt" could reveal about her and her past. Helping patients understand illness is one of our most challenging tasks. Understanding allows us to distance ourselves from the discourse that disease is guilt and punishment: an avoidable outcome resulting from past mistakes we may have made.

The personal experience

But not every patient desires to understand. In "Best American Medical Writing," a collection of texts written by doctors, patients, and family members of patients, I read the story of a patient who eventually was diagnosed with Huntington's disease. Her son, the author Kevin Baker, wrote about the escalating events that culminated in the diagnosis in a spiral that lasted at least ten years: "my mother's denial tormented those of us who loved her. But now I found her desire to cling to the life she had known understandable…".4 It is also up to us to understand and accept those decisions. They teach us that the path walked in illness is personal, despite being universal.

The three main narratives in response to illness

In the second edition of "The Wounded Patient," Arthur Frank tells us how the writing of the first edition of this book, in 1994, was part of his self-healing process.5 After a medical history comprising cancer and sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease, Frank teaches us that "suffering needs stories".5 A "wounded patient" depends on narratives to put the healing path in order. These narratives can be restitutive, focusing on the superation and the cure; chaotic, an unpredictable telling of how disease affects an individual that demystifies the linear journey of illness to healing usually imposed on the sick; or questioning, centered on the meaning and purpose of the journey.5 By writing his own experience and sharing others' narratives, Franks reminds us that "... to tell one's own story, a person needs others' stories".5

In the end, we need words, narratives, stories. To have the cooperation of these during the disease experience, as patients and as doctors, reminds us of the troubles and hopes we all carry. Joan Didion wrote: "We tell ourselves stories in order to live".6 We talk to ourselves, create explanations, and name things and feelings. We do this because we depend on the way we translate reality to live reality in its fullness. Stories must be told to make sense of our lives, which is no different in a life accompanied by illness. That's why I have increasingly subordinated the technical definitions of disease to the descriptions I read in literature. Illness is not only the deviation from normal physiology that affects a human's physical, mental, or social conditions. Disease is also the story a human being tells about it, and knowing how to tell this story is as important for recovery as the medications we can offer.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2023 Pereira. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.