International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Case Report Volume 3 Issue 4

Internal Medicine, Hospital Distrital da Figueira da Foz, Portugal

Correspondence: Ana F Costa, Internal Medicine, Hospital Distrital da Figueira da Foz, Av. 12 de Julho 275, 3094-001 Gala, Figueira da Foz, Portugal, Tel 00351915186182

Received: July 22, 2019 | Published: August 30, 2019

Citation: Costa AF, Almeida F, Batista AF et al. Hyperviscosity syndrome - a case report. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2019;3(4):166-167. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2019.03.00151

Hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS) is a life-threatening complication. The clinical manifestations include a variety of symptoms like visual symptoms, altered mental status, stroke or congestive heart failure. Prompt treatment is needed to avoid progression to multisystem organ failure. We report a case of a 73-year-old man with a 3-months history of headaches and altered mental status. His neurological exam showed symmetrical decreased pain, thermal and tactile sensitivity in the upper and lower limbs and symmetrical decreased muscle strength in the lower limbs. His eye exam showed retinal hemorrhages and dilated retinal veins. His blood counts showed anemia, increased C-reactive protein, sedimentation rate and serum viscosity. He had an elevated immunoglobulin M and serum immunofixation revealed Ig M-kappa paraprotein. The bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed a Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. He was diagnosed with HVS and was treated with plasmapheresis, chemotherapy and fluids. HVS diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion, andclinicians should be aware of suggestive clinical and laboratory findings.

Keywords: waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, hyperviscosity syndrome, plasmapheresis, paraproteinaemia, oncologic emergencies

HVS, hyperviscosity syndrome; Ig, immunoglobulin; WM, waldenström’s macroglobulinemia

Hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS) refers to an increase in serum viscosity secondary to circulating proteins. It can be a result of an hyperproliferation of blood components such as seen en polycythemia and acute leukemias or a consequence of an increase in immunoglobulins.1,2 HVS is most common in patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM), followed by multiple myeloma and leukemia.2,3 The clinical manifestations of HVS include a variety of symptoms like visual symptoms, altered mental status, stroke or congestive heart failure. The diagnosis of HVS should be suspected if it is presented the triad of mucosal or skin bleeding, visual abnormalities and neurologic deficits.3,4 Prompt treatment is needed to avoid progression to multisystem organ failure. The diagnosis is made by clinical and laboratory findings, like increased serum protein levels and increased serum viscosity. Management comprises supportive treatment and plasmapheresis.2,4 We report a case of a patient with HVS as a presentation of WM.

A 73-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 3-months history of headaches and altered mental status (disorientation, agitation and inappropriate behavior). His wife also referred decreased sensitivity of the extremities of the upper limbs with burns in the fingers and progressive loss of autonomy. He denied fever, loss of weight, anorexia, nocturnal hyperhidrosis, hallucinations, seizures, thoracic and abdominal pain. He also denied intake of alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs or herbal products. He had a history of auricular fibrillation, asbestos-related interstitial lung disease and benign prostatic hyperplasia. He was taking folic acid 5mg once daily, iron 329.7mg once daily, carvedilol 6.25mg twice daily, apixaban 5mg twice daily, furosemide 40mg twice daily, quetiapine 25mg once daily and lorazepam 1mg once daily. In the general examination, he was disoriented in time and space with a repetitive speech. He had burns and necrotic lesions on his fingers and toes. (Figure 1) The vital signs were normal, except for a tachycardia of 118 bpm. His physical examination revealed that he was pale, had cardiac arrhythmia and peripheral edemas. He had no palpable hepatomegaly, splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy. His neurological exam showed symmetrical decreased pain, thermal and tactile sensitivity in the upper and lower limbs and symmetrical decreased muscle strength in the lower limbs (grade 3/5).

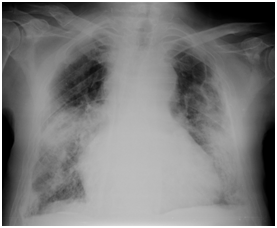

His blood counts showed anemia (hemoglobin 8.6 g/dL) and normal leukocyte and platelet levels. His laboratory investigations showed normal liver and renal enzymes, elevated C-reactive protein (58.44 mg/L, reference value <5 mg/L) and elevated sedimentation rate (121 mm/h). He had elevated folic acid (>20 ng/mL) and B12 vitamin (>2000 pmol/L) with low iron (36 ug/dL, reference value: 61-157 ug/dL) and normal ferritin and transferrin values. His thyroid tests were normal and his proBNP was high (3285 pg/mL, reference value < 300 pg/mL). His total proteins were normal (7.6 g/L) with low albumin (2.9 g/dL, reference value: 3.4-4.8 g/dL) and high β2-microglobulin (5150 ug/L, reference value: 800-2200 ug/L). He had an elevated immunoglobulin M (IgM) 4227 mg/dL (reference value: 40-230 mg/dL) with low IgA (63 mg/dL, reference value: 70-400 mg/dL) and IgG (507 mg/dL, reference value: 700-1600 mg/dL). His urinalysis showed more than 20 leukocytes per uL. His chest X ray revealed an enlarged heart silhouette, bilateral opacities and pleural calcifications compatible with asbestosis. (Figure 2) The cranial computerized tomography (CT) scan was normal for his age.

Figure 2 Chest X- ray showing an enlarged heart silhouette, bilateral opacities and pleural calcifications.

The patient was hospitalized in the Internal Medicine ward with the diagnoses of urinary tract infection, decompensated heart failure and paraproteinaemia. During the hospitalization the paraproteinaemia work-up started. The eye exam showed retinal hemorrhages and dilated retinal veins. The serum viscosity was elevated (2.2 cP, reference value <1.8 cP). Serum immunofixation revealed IgM-kappa paraprotein and urinary immunofixation was normal. The patient had proteinuria with 1.89 g/24h. The bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed an infiltration by small CD20+ lymphocytes in a nodular pattern and the genetic studies showed a positive mutation in MYD88 L265P. The abdominal ultrasonography showed a small hepatomegaly with a normal spleen. The patient was diagnosed with HVS caused by a WM and was transferred for the Hematology ward of the Hospital of University of Coimbra. He started treatment with plasmapheresis, chemotherapy and fluid therapy with an initial good response. He died after 6 months of treatment with an acute infection.

WM is a rare B-cell disorder, characterized by over production of monoclonal IgM, with the median age at diagnosis of 70 years old. Many patients have constitutional symptoms (fevers, night sweats, weight loss, astenia), but substantial number of patients can be asymptomatic. The neuropathy is tipically sensory, bilateral and symmetrical and can evolve to muscle weakness.1,5 The diagnosis is based in the results of bone marrow biopsy and serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation.5,6 HVS is found in 10 to 30% of patients with WM and can be the initial manifestation.2,3 IgM is a large molecular structure secreted as a pentamer and is found mainly in the intravascular structures. Its rich carbohydrate structure allows it to form aggregates, and its cationic nature decreases the repulsive forces of anionic red blood cells which leads to HVS.1,4 The diagnosis of HVS is based in clinical and laboratorial findings (elevated serum viscosity and serum protein levels). The levels of serum viscosity are related to the severity of clinical symptoms. Fundoscopic examination is important because can visualize a patognmonic sign of HVS – the sausage-shaped veins. Other ocular alterations are hemorrhagic and exsudative findings and retinal vein oclusions.2,4,7

After the diagnosis prompt therapy of HVS can prevent life-threatening complications. Supportive treatment is based in intravenous fluids to prevent volume depletion. The primary treatment to revert the HVS complications is plasmapheresis and can reduce serum viscosity by 20 to 30% per session. The definitive treatment is the treatment of the underlying cause and it is chemotherapy in most cases.2,4 In this case, the patient had peripheral neuropathy, retinal hemorrhages and dilated retinal veins associated to necrotic lesions on the extremities. These findings are suggestive of HVS and the association of the diagnosis of WM with an increased serum viscosity made the diagnosis of HVS. The patient was treated with supportive treatment and plasmapheresis for HVS and with chemotherapy for WM as recommended by literature.

In conclusion, the HVS diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion, however the combination of clinical findings like mucosal or skin bleeding, visual abnormalities or neurologic deficitsand laboratory evidence of increased serum protein levels should raise the suspection.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Costa, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.