International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 5

1PhD student in Complex Thinking, Professor Investigator University Foundation Juan N Corpas, Director of the EDUTRANS Research Group, Colombia

2Student of the 8th semester of Medicine, Coordinator of the Juan N, Corpas University Foundation seedbed, Seedbed of Investigation CAFIVI HOSPICE CARE, Colombia

3Student of the 8th semester of Medicine, Researcher University Foundation Juan N Corpas, Seedbed of Investigation CAFIVI HOSPICE CARE, Colombia

4Student of the 8th semester of Medicine, Researcher Juan N Corpas University Foundation, Seedbed of Investigation CAFIVI HOSPICE CARE, Colombia

Correspondence: Manuel Latorre Quintana, Student of the 8th semester of Medicine, Coordinator of the Juan N Corpas University Foundation seedbed, Seedbed of Investigation CAFIVI HOSPICE CARE, Colombia, Tel +057 312 536 1798

Received: August 01, 2018 | Published: September 28, 2018

Citation: Cano MLM, Manuel LQ, Ospina L, et al. Creation of an instrument to measure the quality of life in terminal patient in hospice ECAVIPTE -IH01. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2018;2(5):301-308. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2018.02.00098

In the attention to the patient in palliative care, the term " life quality" is essential and I have grown in importance to first world countries and more recently to underdeveloped countries; this is a dynamic and multidimensional concept, which include numerous spheres of individual and collective development, variables of consideration such as differences between cultures, places and persons. The objective of this paper is to present the final results of the creation of a tool that assesses quality of life in the terminal patient, applicable to the Colombian population that allows its reproducibility in populations with similar characteristics from its validation that additionally meets the limitations of other previously designed tools. The present research project had a mixed approach, in the qualitative stage it sought to collect, analyze and link data from the explanation of social reality. This was done through interviews, life stories and the comparison of existing theoretical models of international instruments that assess the quality of life in terminal patients; this comparison of models recognizes the general characteristics of the HQLI, MQOL and QLQ-C30 instruments, based on grounded theory that involves an analytical process. The interview of structured, directed and individual type that generated contributions in the general organization of the tool and the life story constituted from the spontaneity and the maieutics from the individual experience of the visit to a Colombian hospice. The instrument that was developed contains 6 dimensions such as physical, psychological, spiritual, family, economic, satisfaction of health care and associated symptoms, with a total of 44 items. 12 experts in the specialty of palliative care contributed in the first external validation, and a second assessment that included an expert in language obtaining a cronbach alpha of 0.86.

Keywords: human being, dynamic, influential parameters, life, infectious diseases, chronic diseases, palliative care units, terminal patient, physical symptoms, socio-cultural environment, life quality, palliative, terminal care, hospice

The term "quality of life" is a dynamic and multidimensional concept that includes many spheres of individual and collective development of the human being. Its evaluation is subjective, variable among cultures, places and people, so it can be overvalued or underestimated if it is not measured with valid, reproducible and reliable tools, it is not new for the medical literature, however, it has taken relevance with the investment of the population pyramid of first and, more recently, third world countries.1 International papers have proposed three tools used and authorized in different countries, which allow to identify the influential parameters in the quality of life of the oncological and non-oncological terminal patient; each one of these tools with limitations of identification of personal problems, little evaluation of important physical symptoms, complexity of interpretation and difficult application in practice.2 To determine the quality of life of the terminal patient is fundamental to recognize the factors that influence the well-being in the outcome of life; Colombia as one of the countries in Latin America with deficiencies in education and care in palliative care has reached measured achievements to efficiently recognize this fundamental aspect in a hospice patient who is at the end of his life.3 The recognition of these weaknesses in the tools developed and applied, also allows us to specify that there is no abalada tool to apply to the Latin American terminal patient treated in a hospice, taking into account the dimensions of the human being and their socio-cultural environment.4 As the main causes of morbidity and mortality stopped being occupied by infectious contagious diseases to be replaced by chronic diseases, there was an increase in the life expectancy of the populations and consequently an increase in the need to provide care at the end of life; At the executive level, there is currently no plan for care and attention to the quality of life of the terminal patient.5 Additionally, it is necessary to create an audit system that regulates the quality of care of the services provided in hospices or palliative care units.

On the other hand, in Colombia several centers have been created to offer palliative care and "good death" to patients with these characteristics using models carried out in pioneer countries such as England and Canada, known assets “Hospices” (Hospices). In these centers an attempt has been made to measure the quality of life, seeking: to make early diagnoses of co-morbid and prevalent pathologies in users (depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue, etc.), to establish therapeutic changes and to monitor the evolution of each patient in the environment; through carefully performed, evaluated and validated instruments.6,7 For care in palliative care, there are tools such as the HQLI that recognizes general dimensions and provides general information on the patient's condition, but is weak in identifying personal concerns, physical symptoms such as nausea, and allows economic aspects to be recognized; We must also take into account weak relation with oncological evolution with psycho physiological scales.8 The MQOL as a tool of McGill identifies very well the general state of the patient in the physical dimension, being useful for the nursing staff in such a case to apply in the hospice; but it has significant deficiencies such as the difficulty to be interpreted by the patient, it is not useful to efficiently recognize the spiritual and social aspects.9 Finally, the QLQ-C30 as the instrument that most informs about the quality of life of the patient, because it is an extensive and evaluative questionnaire, although it is very little functional because of the high score, which does not allow to recognize the most affected dimension of the patient; in the same way, it is a tool that is recognized as weak in psychological evaluation, since it is considered imprecise and subjective.10 Therefore, the objective of the project was to create a validated tool applicable to the Latin American population, which would allow evaluating the quality of life in a terminal patient taking into account the socioeconomic, emotional, spiritual and physical factors of the person. ECAVIPTE IH 01 translates "Evaluation of Quality of Life in a Terminal Patient - First Instrument for Hospice ".

The design of this research had a mixed approach that sought to collect, analyze and link qualitative data aimed at the understanding and explanation of social reality through the interview, a story of life and the comparison of the existing theoretical models of the instruments that evaluate the quality of life in oncological and non-oncological terminal patients. It should be understood that qualitative research uses methods such as "the analytical induction that it consists in the study of the data that allows to generate empirical affirmations by means of the construction of key links between the various data. Additionally, the well-founded theory is available, Combined with the data collection and analysis that allows the formulation of an integrated set of conceptual hypotheses, this is achieved first through constant comparison, second the coding: open and axial, and finally the theoretical sampling ".11 The research was carried out in the following methodological phases:

Collection of data as follows

The first phase consisted in applying the interview, the life history and the comparison of the existing theoretical models of the international instruments that evaluate the quality of life in terminal patients; the life story based on spontaneity and maieutic, performed by a sixth semester medical student that allowed to infer and identify in the processes and procedures performed in a hospice, in this story you can highlight the most outstanding facts of this12 experience. One of the most important aspects of this story is the emotional and professional relationship, which allows us to confront the need for an instrument that can measure quality of life in Latin American hospices. On the other hand, the structured, directed and individual interview was conducted to a doctor with more than 10 years experience in the subject of palliative care, where it allowed to identify the influential parameters in the quality of life of the oncological and non-oncological terminal patient, Latin America was identified as a territory with deficiencies in education and care in palliative care; reinforcing the needs of evaluating in the terminal patient factors that influence in their well-being on the part of the professionals who today attend units of palliative care. This model comparison recognized the general characteristics of HQLI instruments (Hospice Quality of Life Index), MQOL (McGill quality of life questionnaire) and QLQ-C30 (The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire);8–10 The comparison of theoretical models is made from "the analytical comparison of events applicable to each category seeking to identify the similarities and differences in the information collected, the second integrates the categories and their properties (subcategories ), the third step delineates the theory obtaining a smaller set of categories of higher conceptual level; and finally the writing of the theory that implies confronting the annotations finding the delimitation of the theory "11

Hospice quality of life index (HQLI)

With 25 items evaluated, it was designed to establish the degree of quality of life in patients with cancer, each item consisting of a visual scale, numbered from 0 to 100mm. The raw score is obtained by measuring the number of millimeters from zero to the mark made by the patient. Each item is then weighted by its importance. The resulting weighted scores can range from 0 to 300, with zero representing the worst possible quality of life and 300 representing the best possible quality of life. The main limitations of this tool are that they do not include personal concerns, physical symptoms such as nausea and the financial relationship and the exclusion of patients with functional impairment.8

McGill questionnaire quality of life (MQOL)

With 17 items that assess the quality of life in patients with a terminal illness. It uses a scale of 1 to 7 and measures four dimensions: physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, perspective of life and significant existence. The main limitations lie in confusing scales for patients, with values assigned that are inverted according to the item, however, in a study that compared the use of two tools for the evaluation of the quality of life, its main advantages were in the time and simplicity during the application, as well as the capacity to determine aspects of improvement in the care programs.9

The EUROPEAN organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)

A questionnaire of 30 items, based on 5 physical, social, emotional, occupational, cognitive dimensions) and three symptomatic sub-dimensions such as: fatigue, pain, nausea and vomiting); the economic impact during the treatment of the oncological patient. Among its advantages are: 25 of the items collect information on the sensations perceived during the last week and is a reliable tool for cancer patients of different types, whose conditions are not expected to change in a specific time, EORTC QLQ-C30.10

Construction of the instrument

The following parameters were taken into account

It began with the construction of the ECAVIPTE IH 01 skeleton based on the identification of the instruments created so far, the comparison of strengths as weaknesses and taking into account the four dimensions of quality of life: physical, psychological, social (economic and family) and spiritual. The physical dimension is evaluated on a scale of 1 to 7 with 7 being the highest score, the psychological and family dimension is evaluated on a scale of 1 to 6, the latter being the maximum score, and finally the economic dimension that is evaluated in a scale from 1 to 4 with 4 being the highest score. In all the dimensions, the scale evaluates the quality of life of the patient with a minimum score of 8 that indicates very good quality of life and 27 the maximum score that indicates poor quality of life. To complete this evaluation, the scale of associated symptoms was added according to the physical and psychological deterioration, which is added to the score obtained previously, producing a score higher than the 27 that diagnose poor quality of life. One of the most common conditions affecting palliative patients are neuropsychiatric syndromes such as delirium, prevalence’s of delirium have been reported in palliative care units ranging from 28 to 42% at the time of admission and up to 88% in periods prior to death,13 the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-V include the following:

Given the prevalence of these conditions in palliative patients, the instrument has a box which can be completed by an evaluator which denote that the patient can not apply the instrument.14

Validation of the instrument created to measure quality of life in the terminal patient

The internal consistency method based on the Cronbach's alpha allows to assess the reliability of a measurement instrument, through a set of items that are expected to measure the same construct; This instrument validity refers to the degree to which the reliability of the internal consistency by Cronbach's alpha estimation. The reliability of the scale must always be obtained with the data of each sample, to guarantee the integral measurement of the construct in the specific sample of research.15 For the validation, an inter-trial procedure was carried out through the creation of a database of more than 36 international professionals in palliative care with degrees in psychology, medicine, nursing, spiritual guidance and physiotherapy. Said database was analyzed according to the components of ECAVIPTE, taking into account this matrix of categories, support was requested by e-mail in the review and evaluation; Responding to this request, 14 experts declared that they had no conflict of interest in the process, completing their function as reviewers and evaluators. The instrument was validated from the qualitative and quantitative aspects; qualitatively the aspect of its content was taken, in terms of the qualitative, the reliability, the constructor, the criterion and the performance were evaluated. The validation was divided into 5 steps, the first consisted in the validity of the content in which the instrument was presented to interdisciplinary experts so that they could approve the items and the results that can be obtained, verifying in this way the viability of the instrument; in this assessment He managed to show the ambiguity of several points proposed in the instrument, for this reason they were reformulated and it was decided to divide the spiritual dimension into two: one where the relationship with the interpersonal god will be evaluated and this in turn is subdivided into 5 sub items asking how good a relationship with this or of being poor this bond between God and the patient generates satisfaction or discomfort, the feelings of conflict that this relationship produces, if it generates discomfort in his illness or if he feels in total abandonment on the part of supreme being; In this way, it is possible to cover any possible religion or spiritual figure that the person has and eliminate the ambiguity of the item.

Another part that will cover the interpersonal part of the patient, evaluating if he feels that his life in the state in which he finds himself has a purpose or if on the contrary he has lost all the meaning, questioning if she is at peace with herself despite being for that difficult moment or if on the contrary he feels guilt with himself and with those around him; Looking to see if you can talk about your life in present, future and past with tranquility or if this generates fear or concern, and finally takes into account whether or not the patient has someone with whom they can express their feelings or concerns, for perform this correction of the initial instrument and add these new parameters was taken as reference to the Spanish Society of Palliative Care (SECPAL).16 Thus, an instrument with 51 items is obtained , where its minimum score is of 8, the maximum score without associated symptoms is of 40 and with the associated symptoms of 59. The instrument is interpreted in the following way: from 8 to 12 it refers excellent quality of life, from 13 to 21 refers a regular quality of life, from 22 to 31 refers poor quality of life (requires intervention by the interdisciplinary team) and equal to or greater than 32 Refers lousy quality of life (requires immediate intervention by team interdisciplinary). After this was taken to a second assessment by a language expert who approves the wording used and the formulation of the questions; the second step was based on the internal consistency in which the Cronbach's alpha was applied to evaluate the reliability and validity of the instrument, in this a score of 0.86 was obtained, which indicates that the instrument is totally reliable. The third step was the validity of the construct that was carried out by means of a factorial analysis where groups were established in the different dimensions of the instrument, in the fourth step the stability of the instrument was evaluated in which several measurements were required in order to give a judgment of the results, determining that they are stable and unambiguous. Finally, the performance of the instrument was evaluated with the aim of minimizing errors at the time of making a judgment. This research was approved by the ethics and research committee of the Juan N. Corpas University Foundation.

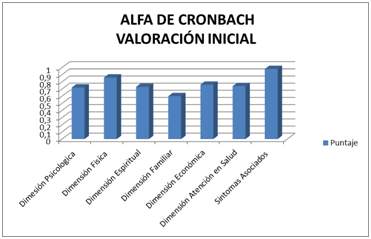

When reviewing the literature and existing models, there are weaknesses in the spiritual, physical, emotional and patient care dimensions in these instruments2–16 therefore there is no instrument that meets the criteria for measuring the quality of life in a palliative patient that can be applied to Colombian society and culture. Taking into account the above, the instrument is made up of 6 dimensions such as physical, psychological, spiritual, family, economic, satisfaction of health care and associated symptoms, obtaining a total of 44 items which were sent to external validation for be evaluated by 12 experts in the specialty of palliative care;15 obtaining the following validation results see Figure 1:

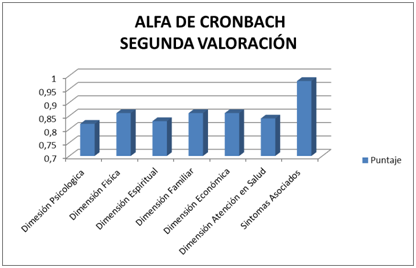

After the modifications, an instrument with 51 items is obtained, where its minimum score is 8, the maximum score without associated symptoms is 40 and with the associated symptoms of 59. The instrument is interpreted: from 8 to 12 it refers excellent quality of life, from 13 to 21 refers a regular quality of life, from 22 to 31, refers to poor quality of life (requires intervention) and equal to or greater than 32, refers to a poor quality of life (requires immediate intervention by an interdisciplinary team); This result is obtained from the qualification obtained from the revalidation by the experts, which recognizes that ECAVIPTE IH 01 is a reliable instrument with practical utility see Figure 2. The physical dimension makes an approach of the most prevalent symptom in the terminal patients as it is the pain, the quick interpretation by the patients is sought with a simple scale; this dimension is complemented with an assessment of the most prevalent symptoms at the end of life of oncological and non-oncological patients (Table 1) & (Table 2). The personal psychological dimension seeks to relate the current state of the patient and their capacity for acceptance (resilience) with the lived process, this dimension is based on the subjective interpretation of the patient's state and the emotions expressed at the time of the interview See Table 3. The spiritual dimension is associated with the development of qualities and values that foster love and peace. The human being is the owner of an inner, intimate dimension, indispensable for the development and transcendence of life. In this dimension, the relationship of the patient with his spiritual being and with himself is evaluated (Table 4). The social dimension is divided into two columns, the family where it is based on the value of the family as a vital space for socialization, a protective environment for people at the end of life, as well as each of the members of their family group and the emotional influence it has on the patient's pathological state and the way in which they assume grief. The second column evaluates the economic factors, which is very important because it recognizes the impact of the financial and material stability aspects on the transit between life and death (Table 5). The dimension of health care seeks to identify the state of patient satisfaction in the health system that governs it according to social and demographic aspects (Table 6).

Figure 1 It recognizes a useful instrument with weaknesses for the interpretation, approach and relationship with the general state of the patient, suggests modifications and improvements to recognize its viability.

Figure 2 It represents the obtained results that allowed to obtain a definitive instrument with a Cronbach's alpha superior to 0.8.

Physical dimension |

P. max:7 |

Associated symptoms |

Score |

He feels comfortable and does not have pain |

1 |

Sickness |

2 |

Identify or report mild pain |

2 |

Threw up |

4 |

Identify or report moderate pain |

3 |

Diarrhea |

2 |

Identify or report pain that impairs the cognitive or emotional state |

4 |

Constipation (constipation) |

1 |

Identify or report intense pain, watery |

5 |

Anorexy |

1 |

Identify or report pain that does not allow you to sleep |

6 |

Asthenia and adynamia |

2 |

Identify or report pain for more than 48 continuous hours without improvement |

7 |

Muscle spasm |

1 |

Psychological dimension |

P. max: 6 |

||

He feels and identifies himself in good spirits (quiet, not easy crying) |

1 |

Cough |

1 |

Feel or identify frustration with the disease |

2 |

Insomnia |

2 |

Consider that the process experienced is a problem. |

3 |

Dehydration (dry mouth) |

3 |

It presents moments of anguish more than twice a day. |

4 |

Delirium |

5 |

It presents moments of anxiety more than twice a day. |

5 |

Dyspnoea |

5 |

Depression is felt or identified (without psychiatric treatment) |

6 |

Table 1 Physical dimension, Physical dimension, associated symptoms, and Psychological dimension. Physical dimension is evaluated with a maximum score of 7 and a minimum score of 1

If the patient refers or presents any of these symptoms, the additional value will be added to the final score. The psychological dimension is evaluated with a maximum score of 6 or a minimum of 1.

Associated symptoms Score |

Source |

Nausea |

2 |

Vomiting |

4 |

Diarrhea |

2 |

Constipation (constipation) |

1 |

Anorexia |

1 |

Asthenia and adynamia |

2 |

Muscle spasm |

1 |

Cough |

1 |

Insomnia |

2 |

Dehydration (dry mouth) |

3 |

Delirium |

5 |

Dyspnea |

5 |

Table 2 If the patient refers or has any of these symptoms, the additional value will be added to the final score

Psychological dimension |

P. max: 6 |

He feels and identifies himself in good spirits (quiet, not easy crying) |

1 |

Feel or identify frustration with the disease |

2 |

Consider that the process experienced is a problem. |

3 |

It presents moments of anguish more than twice a day. |

4 |

It presents moments of anxiety more than twice a day. |

5 |

Depression is felt or identified (without psychiatric treatment) |

6 |

Table 3 psychological dimension is evaluated with a maximum score of 6 or a minimum of 1

Spiritual dimension |

|||

Religion and spiritual belief (Christian, Catholic, Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu, Taoist, Evangelist, Hermeneutic, Gnostic, other.) |

P. max:4 |

Interpersonal |

P. max: 8 |

According to your religion or spiritual belief you consider that you have good relationship with your god |

1 |

Consider that at this moment your life has a meaning or purpose. |

1 |

He has no spiritual belief or support and is comfortable with that state. |

1 |

Consider that your life currently has no meaning or purpose. |

2 |

He has conflict with his god since the beginning of his illness |

2 |

He feels that he is at peace with himself and with those around him. |

1 |

He feels little support of his religious belief in this process. |

3 |

Feel guilt with himself, with whom he surrounded him or with something in particular |

2 |

Feel abandoned by your god in this disease process |

4 |

Feel that you can talk about your life, your present, past and future with ease. |

1 |

Feel fear or worry about your past, present or future. |

2 |

||

Feel that you have someone with whom you can calmly express your thoughts. |

1 |

||

Feel that you do not have someone to express and listen to your thoughts |

2 |

Table 4 Spiritual dimension

The concept of quality of life has a strict relationship with culture because it is recognized as "individual perception of the position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which one lives and its relationship with goals, expectations, standards and interests,17 so that the instruments proposed so far in order to develop an adequate management of the terminal patient, they would not have adequate adherence because their origin dates from developed countries with a socioeconomic system completely different from the countries that make up Latin America . Bearing in mind that the definition of quality of life in the terminal patient is a priority, since it guides the appropriate and timely interventions by an interdisciplinary team in palliative care, which according to concepts its priority is "to provide relief of symptoms and stress of a serious illness, regardless of the diagnosis, its objective is to improve the quality of life of both the patient and the family ";6 contributing to the fulfillment of this in patients from Latin America is proposed ECAVIPTE IH 0.1 that allows the assessor to identify the existence of problems easily discriminating the other dimensions of being, recognizing the most affected, focusing in the best way care at the end of life . Leading professional experts in Latin countries in terminal patient care in hospice models recognized the importance of creating a tool to improve the provision of services, which allows recognizing what in their daily work becomes complex and unrecognizable, as are the most significant needs of the patient at the end of life.

Existing instruments have limitations to provide the conditions that are needed to address palliative patient care, because many of them have biases evaluated in international studies and are not easily applicable for the Latin American population; this lack suggested the creation of an own instrument, which solved the shortcomings of the internationally validated ones and that also fulfilled the needs of the concept of quality of life. Among the instruments that assess quality of life, we can highlight "HQLI that evaluates the oncological patient by means of four sub scales, with 28 items, measuring the physical, functional, psychological and physical well-being dimensions";7,8 This scale is strong in achieving the identification of the healthy and terminally ill patient, and some of its weaknesses are the psycho- physiological sub-scales , as well as its disadvantages, such as economic aspects and physical symptoms. The other instrument is MQQL, which evaluates terminal patient quality of life with 17 points to evaluate, on a scale of 1 to 7, "measures symptoms physical, psychological, life perspective and significant existence, and it is useful to evaluate the physical conditions of the hospitalized terminal patient " 9 one of the strengths of this instrument is its ease and clarity when implementing it but it has important disadvantages such as the approach of the spiritual, psychological and social dimensions, and some items are difficult to interpret by patients. And finally one of the most recognized instruments called QLQ-C 30 which, like the others, evaluates quality of life in hospitalized terminal patients addressed to cancer patients, "their 30-item questionnaire, based on 5 sub-scales, evaluates the physical, social dimensions , emotional, occupational and cognitive, the three sub-symptomatic scales evaluate fatigue, pain, nausea and vomiting " 10 ; As for its advantages, it is considered reliable in oncological patients, whose conditions are not expected to change suddenly, the psychometric evaluation is valid for patients in palliative care unit, recognizes economic aspects of the oncological patient. Its most important weaknesses are high scores because they are not functional; the psychological scale is considered inaccurate and subjective, and the experts do not recommend making a general score to be functional.18,19

Therefore, ECAVIPTE IH 01 is an instrument that evaluates all the dimensions of the human being,20 each of the items were established according to the parameters of care and the interdisciplinary team that should be in charge of the interventions in the patient in order to lifetime; Due to the importance of the relationship between the Latin American patient and health care, the instrument evaluates this perception in detail, allowing factors associated with health services to be attended in a timely and competent manner. Each of the items was written in compliance with writing and linguistic parameters that allow rapid interpretation by patients, thus facilitating their development and clinical applicability. The physical dimension meets two fundamental objectives in the terminal patient, the first is the assessment of pain as the most relevant and important symptom in oncological and non-oncological patients, this parameter may facilitate efficient interventions in pain management and the realization of studies related to opioid disposition and pain management, as it is applied and the importance that it takes in palliative care.21,22 The second fundamental point is the complete evaluation of the additional symptoms that produce progressive deterioration,23 for the evaluation of them a scale that characterizes the damage and the loss of quality of life that they produce is taken into account; these symptoms are the product of the same terminal pathology and its course, or as a side effect to the support drugs.24,25

ECAVIPTE IH 01 carries out a holistic approach to the spiritual dimension, seeking to optimally identify the problems generated from the terminal diagnosis and the impact that this produces on the interaction being superior-person and the interpersonal relationship; this in order to make optimal interventions that generate from this dimension a source of support and resilience for the patient. These items are fundamental for the instrument, taking into account the importance for Latin Americans of their affiliation with religious institutions and spiritual support.26,27 The scales have short ranges, so that the utility of the instrument in clinical practice is precise with respect to the existence or not of deterioration of quality of life and the dimensions that need intervention; this characteristic allows this instrument to be a viable tool in hospice-type centers and in palliative patient care units. This characteristic also facilitates the communication of the interdisciplinary teams and contemplates joint intervention plans of short and medium term, acting directly on the quality of life of the patient at the end of life. The evaluation of ECAVIPTE IH 01 is proposed for future research in the clinical practice applied to the population for which it was designed, complying with the parameters and regulations stipulated by each terminal patient care center; This assessment parameter would allow the instrument to leave the research process and fulfill its objective for the benefit of patients at the end of life, which is consistent with the objectives of health systems throughout Latin America. Therefore, the proposed instrument responds to the need to strengthen the comprehensive care of the terminal patient, in conditions of little progress in care, education and research in end-of-life care; as demonstrated by the Latin American palliative care map 28. In Latin America, the number of terminally ill patients and the needs for care increases progressively, but the training and the formation of teams that meet these needs does not advance. 3 ECAVIPTE IH 01 is paid to the search for quality of life in patients who complete their earthly cycle, since its construction was based on the characterization of the population to which it will be applied.

We appreciate the support of the Juan N. Corpas University Foundation, research tutors and the availability of the Hospice Hospice hospice center.

The authors declare no conflict of interest and the present project was carried out within the ethical framework and responsibility of the research committee of the Juan N. Corpas University Foundation.

©2018 Cano, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.