International Journal of

eISSN: 2381-1803

Opinion Volume 6 Issue 2

Department of pharmacology, Karnataka College of pharmacy, India

Correspondence: Joseph Vinod, Department of pharmacology, Karnataka College of pharmacy, India

Received: February 12, 2017 | Published: March 31, 2017

Citation: Nagarathna PKM, Vinod J, Naresh K, Nader (2017) What Is More Safe and Healthy – Rice or Wheat. Int J Complement Alt Med 6(2): 00183. DOI: 10.15406/ijcam.2017.06.00183

In recent times the talk of the town among the nutrition community and general public has been that consumption of wheat is not good for individuals because of the presence of gluten.Here in this article the authors have tried to look into the scientific evidence of the so called “gluten allergy myth” and have thrown some light on the benefits of consuming wheat over rice.

Rice vs.chapatti (wheat roti) is a very common and controversial topic; both these grains being the staple food in many parts of the globe. People blame rice for causing obesity, diabetes and related conditions. Is it really true?

Basically, we most commonly use polished / white rice, which looks white due to the removal of fiber-rich outer covering (husk and bran). During this process, most of the micro-nutrients (vitamins and minerals) are washed away. Thus white rice is devoid of B complex vitamins, iron, calcium etc.

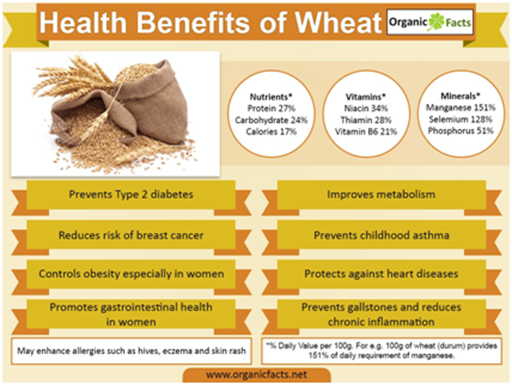

Whole wheat flour, the main ingredient in chapattis, is high in fiber (unless sieved), protein and minerals like iron, calcium, selenium, potassium and magnesium.

Thus, nutrient content-wise, chapattis are healthier than rice. Brown or unpolished rice could be a good replacement for white one which retains almost all micro-nutrients.

|

Comparison |

||

|

Nutrients |

Rice (polished)1 bowl (30 gm) |

Chapattis (whole wheat roti)1 medium (30g flour) |

|

Carbohydrates (grams) |

23 |

22 |

|

Proteins (grams) |

2 |

3 |

|

Fats (grams) |

0.1 |

0.5 |

|

Fibers (grams) |

0.1 |

0.7 |

|

Iron (mg) |

0.2 |

1.5 |

|

Calcium (mg) |

3 |

12 |

|

Energy (KCal) |

100 |

100 |

Some other important considerations are

Gluten

Wheat contains gluten but rice doesn’t, which means that there’s no contest between the two if you’re following a gluten-free diet. Gluten is a protein in wheat that causes inflammation of the small intestine in people who have celiac disease or an allergy to wheat. Rice flour is a commonly used substitute for wheat flour in gluten-free products.

In 2011, Peter Gibson, a professor of gastroenterology at Monash University and director of the GI Unit at The Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, published a study that found gluten, a protein found in grains like wheat, rye, and barley, to cause gastrointestinal distress in patients without celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder unequivocally triggered by gluten. Double-blinded, randomized, and placebo-controlled, the experiment was one of the strongest pieces of evidence to date thatnon-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), more commonly known as gluten intolerance, is a genuine condition.

By extension, the study also lent credibility to the meteoric rise of the gluten-free diet. Surveys now show that 30% of Americans would like to eat less gluten, and sales of gluten-free products are estimated to hit $15 billion by 2016-that's a 50% jump over 2013's numbers!

But like any meticulous scientist, Gibson wasn't satisfied with his first study. His research turned up no clues to what actually might be causing subjects' adverse reactions to gluten. Moreover, there were many more variables to control! What if some hidden confounder was mucking up the results? He resolved to repeat the trial with a level of rigor lacking in most nutritional research. Subjects would be provided with every single meal for the duration of the trial. Any and all potential dietary triggers for gastrointestinal symptoms would be removed, including lactose (from milk products), certain preservatives like benzoates, propionate, sulfites, and nitrites, and fermentable, poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates, also known as FODMAPs. And last, but not least, nine days’ worth of urine and fecal matter would be collected. With this new study, Gibson wasn't messing around.

37 subjects took part, all confirmed not to have celiac disease but whose gastrointestinal symptoms improved on a gluten-free diet, thus fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for non-celiac gluten sensitivity. They were first fed a diet low in FODMAPs for two weeks (baseline), and then were given one of three diets for a week with either 16 grams per day of added gluten (high-gluten), 2 grams of gluten and 14 grams of whey protein isolate (low-gluten), or 16 grams of whey protein isolate (placebo). Each subject shuffled through every single diet so that they could serve as their own controls, and none ever knew what specific diet he or she was eating. After the main experiment, a second was conducted to ensure that the whey protein placebo was suitable. In this one, 22 of the original subjects shuffled through three different diets - 16 grams of added gluten, 16 grams of added whey protein isolate, or the baseline diet- for three days each.

Analyzing the data, Gibson found that each treatment diet, whether it included gluten or not, prompted subjects to report a worsening of gastrointestinal symptoms to similar degrees. Reported pain, bloating, nausea, and gas all increased over the baseline low-FODMAP diet. Even in the second experiment, when the placebo diet was identical to the baseline diet, subjects reported a worsening of symptoms! The data clearly indicated that a nocebo effect, the same reaction that prompts some people to get sick from wind turbines and wireless signals, was at work here. Patients reported gastrointestinal distress without any apparent physical cause. Gluten wasn't the culprit; the cause was likely psychological. Participants expected the diets to make them sick, and so they did.The finding led Gibson to the opposite conclusion of his 2011 research:

In contrast to our first study… we could find absolutely no specific response to gluten

Instead, as RCS reported last week,FODMAPS are a far more likely cause of the gastrointestinal problems attributed to gluten intolerance. Jessica Biesiekierski, a gastroenterologist formerly at Monash University and now based out of the Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders at the University of Leuven in Belgium,* and lead author of the study alongside Gibson, noted that when participants consumed the baseline low-FODMAP diet, almost all reported that their symptoms improved!

"Reduction of FODMAPs in their diets uniformly reduced gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue in the run-in period, after which they were minimally symptomatic."

Coincidentally, some of the largest dietary sources of FODMAPs- specifically bread products -- are removed when adopting a gluten-free diet, which could explain why the millions of people worldwide who swear by gluten-free diets feel better after going gluten-free.

Indeed, the rise in non-celiac gluten sensitivity seems predominantly driven by consumers and commercial interests, not quality scientific research.

"On current evidence the existence of the entity of NCGS remains unsubstantiated," Biesiekierski noted in a review published in December to the journal Current Allergy and Asthma Reports.

Consider this: no underlying cause for gluten sensitivity has yet been discovered. Moreover, there are a host of triggers for gastrointestinal distress, many of which were not controlled for in previous studies. Generally, non-celiac gluten sensitivity is assumed to be the culprit when celiac disease is ruled out. But that is a "trap," Biesiekierski says, one which could potentially lead to confirmation bias, thus blinding researchers, doctors, and patients to other possibilities.

Biesiekierski recognizes that gluten may very well be the stomach irritant we've been looking for. "There is definitely something going on," she told RCS, "but true NCGS may only affect a very small number of people and may affect more extra intestinal symptoms than first thought. This will only be confirmed with an understanding of its mechanism."

Currently, Biesiekierski is focused on maintaining an open mind and refining her experimental methods to determine whether or not non-celiac gluten sensitivity truly exists.

Depending on how long you’ve been gluten-free, you have probably debunked a few myths. No, you did not go gluten-free just to lose weight. No, you really can’t “just try” a bite of that sandwich.

This time, the myths come from within the gluten-free community. Yes, with all the information and connections available on the Internet, even the nutrition community struggles with misconceptions from time to time. Here are some of today’s top myths and the truth behind them: If it says “Manufactured in a facility that also processes wheat,” it’s not safe for people with celiac disease.

The above is an example of what the FDA calls a voluntary allergen advisory statement. It is different from a “contains wheat” statement, which is required by law and means that the food definitely includes wheat. The voluntary warning, on the other hand, means that the product is not made with those allergens, but there may be a risk of cross-contact in the manufacturing process. The statement can seem alarming, but in some cases it may mean that the company is going above and beyond to let customers know about their processes.

If you find a product that is labeled gluten-free but bears a warning like this one, you can rest assured that the product must comply with the gluten-free labeling law. Even though foods can have allergen advisory statements for wheat, if they are also labeled gluten-free, the product must meet the requirements of the gluten-free labeling rule. Basically, these labels are voluntary and the absence of an advisory statement does not automatically mean a product is produced in a dedicated gluten-free facility.

If you’d like to investigate a product further, Beyond Celiac suggests visiting the company’s website or calling their hotline to learn more about their manufacturing practices. It’s absolutely possible for a manufacturer to produce safe gluten-free food for people with celiac disease using shared equipment or a shared facility, as long as they have the proper sourcing, cleaning, storage, production and testing protocols in place to keep the food safe.

Gluten-free food should contain zero gluten

This seems like a simple expectation, but in reality it’s nearly an impossible feat – and one that would severely limit our food supply. Our current methods for gluten detection will test to 3 parts per million (ppm) at the lowest and other more reliable tests will detect as low as 5 ppm. Even if we are able to test for zero ppm in the future, that level would be so strict that it would be likely that many manufacturers simply couldn’t reach it – and those that do would potentially carry an even higher price tag. Most importantly, researchers agree that most people with celiac disease can safely tolerate up to 20 ppm of gluten. Even so, many manufacturers are testing at even lower levels so they can be accessible to more sensitive individuals.

Based on testing hundreds of samples of food products labeled gluten-free through Tricia Thompson’s Gluten-Free Watchdog using the formally validated sandwich R5 ELISA Mendez Method, the vast majority of product samples are testing well below 20ppm.

You don’t have the same symptoms as your family member, so you don’t have celiac disease

We all know that celiac disease can be quite a chameleon, and that can also be the case within a family. Just as it’s not uncommon for one person to have severe gastrointestinal problems, another to have anemia and another to have no symptoms at all, the same holds true for family members. Because first and second-degree relatives have an increased risk of developing celiac disease (1 in 22 for parents, siblings, children; 1 in 39 for aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces, cousins, grandparents, half-siblings), celiac disease experts recommend family member testing as a proactive approach to diagnosis.

Most celiac disease physicians suggest relatives get a blood test at the same time their family member is diagnosed and then every 2 to 3 years or anytime potential symptoms emerge. Because celiac disease can develop at any age, it’s possible for a relative to have an initial negative test result, but then test positive 12 years later. A genetic test can help to determine your risk and can even rule out celiac disease if a person is found to not carry the celiac disease genes.

Celiac disease is on the rise because today’s wheat is different than it used to be

There are many theories as to why celiac disease is becoming more and more prevalent. One of those theories is that wheat has been bred to contain higher amounts of gluten. According to Donald Kasarda, PhD, Collaborator, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Beyond Celiac Scientific/Medical Advisory Council member, that theory falls flat. Dr. Kasarda published a study last year that found that wheat breeding was not to blame for the rise in celiac disease. Other factors, such as overall wheat consumption or an additive known as “vital wheat gluten,” are potential areas to explore in the future, but so far no definitive causes have been identified. As research continues, you can expect to see more myths busted in the future. Take this as an opportunity to start reading more about the latest news in celiac disease and the gluten-free diet, and always choose credible sources!

As we have seen in this article there is clearly no doubt that wheat is a better choice over rice and the myth that gluten allergy affects all those who eat wheat is false and has been scientifically disproven by various clinical trials and one such as be mentioned here. Hence the take home message is to suggest wheat over rice for patients who are diabetic and those who are avoiding wheat because of gluten allergy should get rid of that fear and enjoy wheat without any fears.

None.

None.

None.

©2017 Nagarathna, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.