International Journal of

eISSN: 2381-1803

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 6

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Florida, USA

1 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Florida, USA

2Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, USA

2 Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, USA

3Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, USA

3 Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, USA

4Ponce Health Sciences School of Medicine, Ponce Health Sciences University, USA

4 Ponce Health Sciences School of Medicine, Ponce Health Sciences University, USA

Correspondence: Vani J Sabesan, Department of Orthopedics, Cleveland Clinic Florida 2950 Cleveland Clinic Boulevard, Weston, FL 33331, USA, Tel (954) 659-5430

Received: October 13, 2020 | Published: December 30, 2020

Citation: Meiyappan A, Rudraraju RT, Sheth B, et al. Regenerative medicine: what can it do for me? Int J Complement Alt Med. 2020;13(6):244-250. DOI: 10.15406/ijcam.2020.13.00523

Objectives: Patients now have longer life expectancies and more active lifestyles which is driving the growth and use of regenerative medicine. Definitions of regenerative medicine (RM) vary, with much of the public having an incomplete understanding of what regenerative medicine means or the science behind these therapies. The purpose of this study was to assess patient perceptions and understanding of the role of regenerative medicine in treating musculoskeletal problems.

Methods: This cross-sectional study consisted of an anonymous self-administered survey designed to assess patient perceptions, knowledge and attitudes toward regenerative medicine and its application in sports medicine of 150 participants. The demographic information and participant’s knowledge and conceptions of regenerative medicine were surveyed from patients in an orthopedic surgery department at a single institution. Descriptive statistics were used to report survey data. Analyses were performed based on demographic variables using independent t-test and an analysis of variance (ANOVA).

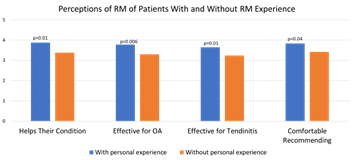

Results: Of the survey takers, 70% viewed RM therapies positively. Participants with a positive view scored significantly higher in all aspects of the survey including effectiveness in the clinical setting (p<0.05) and the likelihood to use or recommend RM therapies (p<0.05). Older Participants (over 54years) scored higher for basic knowledge on RM (3.63; p=0.02). Participants with personal experience with RM had a more positive response when asked if it helps their condition (3.87 vs. 3.38; p=0.01) and were more comfortable recommending it to others (3.83 vs. 3.41; p=0.04).

Conclusion: Overall, participants had a moderate level of understanding and positive perception of the effectiveness of RM therapies. Our results showed participants had a positive view of these treatment modalities despite the literature not supporting the effectiveness of these therapies. More research should be dedicated to this area of medicine given the public interest and desire for RM treatments.

Keywords: regenerative medicine; platelet rich plasma; arthritis treatment; patient perceptions; alternative therapy; orthopedics

ANOVA, analysis of variance; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; FDA, food and drug administration; RM, regenerative medicine; SD, standard deviation

Regenerative medicine is a relatively novel branch of medicine that involves the use of biological substances, such as stem cells, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and bone marrow aspirate to aid healing and regeneration of injured tissues.1–4 Significant preclinical data suggests there is great promise for such therapies in both neurodegenerative and musculoskeletal disorders. Such promise appears to position regenerative medicine as a welcome alternative to surgical intervention or prolonged physical therapy.1,5–8 However, success in clinical settings is quite limited and only few approved regenerative medicine therapies exist for musculoskeletal pathologies.9–11 As such, the use of regenerative medicine is currently limited as only a few clinical trials that have been conducted and those have failed to show consistent results supporting the safety and efficacy of regenerative medicine.12

Chronic musculoskeletal pain remains one of the most commonly reported problems in the United States, a reported 108 million people had a musculoskeletal related problem lasting for at least 3months.13 The treatment options for these patients are usually limited to physical therapy or corrective surgery, which can prove ineffective or painful.14 Regenerative medicine is able to provide a yet unexplored pathway for treating these patients. Many basic science and pre-clinical investigations have focused on muscle, tendon and bone injury and have been targeted for use in sports medicine.10,15 Availability to the public depends on FDA approval, which requires several years of stringent testing and clinical trials.5,15,16 Additionally, regenerative therapies are costly, which further limits the number of people to whom RM is accessible. Nevertheless, people are still willing to make substantial financial investments into these types of treatments, despite the limited literature available attesting to their effectiveness.

The market for regenerative medicine is growing exponentially and predicted to reach $67.5billion by 2020.1 Researchers have been exploring methods to replace and regenerate damaged or pathological tissue using mesenchymal cells or platelet rich plasma (PRP).17 Treatment with PRP has been the frontrunner as a source for regenerative cells as studies with level 1 evidence have highlighted its effectiveness in treating knee OA and lateral spondylopathy. Other sources including bone marrow and adipose tissue have been explored as possible sources of mesenchymal stem cells but have not been able to demonstrate greater effectiveness than PRP formulations. Bone marrow stem cells are concentrated into what is known as bone marrow aspirate concentrate. The formulation has been studied, but hasn’t demonstrated level 1 evidence of effectiveness in musculoskeletal injury treatment.

Adipose cells, like bone marrow cells have shown effectiveness on their own in regeneration of tissues, but fail to show this in clinical trials. Both are strictly regulated by the FDA, with specific formulations approved for use. The only studies demonstrating level 1 evidence of effectiveness of adipose cell formulations uses a form of adipose tissue that is not FDA approved for use in the United States. Further investigation is required on all three formulations, but especially for adipose and bone marrow derivatives in order to establish themselves as potential treatment in musculoskeletal injuries.

Cell-based regeneration offers a safe and potentially effective treatment for patients with musculoskeletal injury, however while the non-clinical trials have proven promising, there is paucity of information regarding the public’s conceptions and attitudes toward this rapidly expanding field.18

The primary objectives of this study were to determine perceptions (positive or negative) patients held toward the use of novel regenerative medicine and to determine whether the demographic characteristics of patients would affect their views on the use of regenerative medicine.

Study design and setting

An IRB approved questionnaire (Figure 1) and case scenarios (Figure 2) were administered to patients in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at a single institution. The survey assessed the current attitudes and patient perceptions towards the use of these new technologies. The anonymous questionnaire encompassed the subjects’ current knowledge, likelihood to use or recommend, and general attitudes towards regenerative medicine. Furthermore, demographic characteristics of the patient including age, gender, education and ethnicity were collected. This two-part survey employed a 5 and 7 points Likert scale to measure responses on a sliding scale and made use of binary yes or no questions as well as self-reported responses to certain questions.

Selection of participants

Potential participants were recruited in 2018 in the orthopedic department waiting room of a single institution. We approached a convenience sample of all patients and families of patients irrespective of reason for visit during the collection period. No specific inclusion or exclusion criteria were employed except for age greater than 18. There were no incentives or benefits offered for enrolling in this study. After consenting, participants completed a basic written survey relating to their knowledge and perception of regenerative medicine as well as basic demographic information. Data was then imported into a Redcap database where it could be stored, coded, and analyzed. 150 participants were enrolled in this study.

Data analysis

Survey results were coded from a qualitative scale to a quantitative scale from 1-5 with 1 corresponding to “strongly disagree” and 5 corresponding to “strongly agree” responses. Descriptive statistics with frequencies were used to report overall survey data. Analyses were performed based on demographic variables using an independent t-test and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if there was any demographic predisposition to certain beliefs towards regenerative medicine. All analyses were completed using SPSS Software (IBMCorp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Characteristics of study Subjects

This study had 150 participants, 51.3% were male and 48.7% were female and 68% of the population group were over the age of 55. The majority (76%) of the participants identified as Caucasian. Most participants reported an education level of having a college degree or higher (80.1%) and an income of over 90,000 USD (62.1%) (Table 1).

Demographic variable |

Percentage (n=152) |

|

Gender |

Female |

48.6 |

Male |

51.3 |

|

Age group |

18-24 |

3.2 |

25-34 |

4.6 |

|

35-44 |

10.5 |

|

45-54 |

14.4 |

|

55-64 |

26.3 |

|

65-74 |

29.9 |

|

75 and up |

15.7 |

|

Highest level of education |

High School Graduate |

13.8 |

Vocational Training |

5.9 |

|

Some college |

13.1 |

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

26.3 |

|

Masters or Professional Degree |

22.3 |

|

Annual household income |

Less than $30,000 |

5.2 |

$30,000-$60,000 |

11.8 |

|

$60,000-$90,000 |

12.5 |

|

$90,000-$120,000 |

11.1 |

|

$120,000- $150,000 |

12.5 |

|

over $150,000 |

23.6 |

|

Race |

White/Caucasian |

75 |

African American |

13.1 |

|

Asian |

4 |

|

Multiracial |

1.3 |

|

Other |

6 |

|

Ethnicity |

Hispanic |

20.4 |

Non-Hispanic |

79.6 |

Table 1 Survey participant responses to demographic question

Questionnaire results

Overall, participants rated their understanding of RM at 3.49 (SD+/- 1.024), RM would help their condition at 3.50 (SD +/-0.83), comfortable with RM treatment at 3.55 (SD +/- 1.03), effectiveness of regenerative medicine as a therapy at 3.55 (SD+/- 1.03), effective for osteoarthritis at 3.40 (SD+/-0/75), effective for tendinitis at 3.32 (SD+/- 0.73), comfortable in recommending RM at 3.49 (SD+/-0.89) and likelihood to consider regenerative medicine as an alternative to surgery at 3.85 (SD+/- 0.92) (Figures 3&4)

Figure 4 Figure 4 Comparison of Perceptions of Regenerative Medicine Therapies for Patients Compared Based on Personal Experience.

Regenerative medicine therapies were seen in a positive light by 75% of survey takers. Questions answered by participants can be seen in percentage distributions (Table 1). Participants with a positive view scored significantly higher in all aspects of the survey including effectiveness in the clinical setting (p<0.05), leading an active life where sport and physical activity play a large role (p=0.02) and the likelihood to use or recommend (p<0.05). Education status did not show a significant difference in mean response between participants when asked to assess the effectiveness of regenerative medicine for osteoarthritis and tendinopathy (p>0.4), comfort in recommending this therapy to others (p=0.2) or if they would opt to choose this alternative to surgery.

Older Participants (over 54years) scored higher for basic knowledge on RM (3.17 vs. 3.63; p=0.02). Participants with personal experience with RM had a more positive response when asked if it helps their condition (3.87 vs. 3.38; p=0.01), think it is effective for OA (3.77 vs. 3.3; p=0.006) or tendinitis (3.64 vs. 3.23; p=0.01), and are comfortable recommending it to others (3.83 vs. 3.41; p=0.04).

In seeking newer treatments for any condition, patients desire safety and efficacy, particularly in circumstances where traditional treatment options seem limited or have been exhausted. The significance of this survey and data collection is to understand patients’ perceptions, design clinical guidelines, improve patients’ safety and learning. Several surveys have shown an association between some of the socio-demographic variables and the level of knowledge and understanding in different areas of medical science but there is no such study published to our knowledge regarding patient’s’ perceptions in the field of regenerative medicine (RM) for treating musculoskeletal injuries.15,19

Our results show survey takers had a positive view on RM and scored significantly higher on effectiveness in the clinical setting (p<0.05) and the likelihood to use or recommend (p<0.05). We believe that patients were more knowledgeable and had positive perception on regenerative medicine because they were not completely satisfied with the existing treatment options available for musculoskeletal problems and probably desired cell therapy and other regenerative medicine therapies. Such belief is also in line with previous observations which found a higher level of knowledge on specific conditions among patients.20 Interestingly, a high level of perception of regenerative medicine was observed among older participants. Our results also suggest that older age groups are favorable to educational training in regenerative medicine. Furthermore, the significant difference between the age groups in regard to knowledge on regenerative medicine may be explained by the fact that older participants were more up-to-date on clinical developments and current standards of care.21 This observation is in agreement with other studies which reported age as a predictor of beliefs among patients.22 At first glance, this may also imply that they are willing to improve their knowledge and probably prefer being treated with this new modality.

Overall, our results indicate patients have a high level of knowledge about regenerative medicine (RM) and have a broad knowledge of available options and approved therapies. Moreover, education status did not show a significant difference between participants when asked about effectiveness of regenerative medicine for osteoarthritis and tendinopathy. Patients answered they are very comfortable in recommending this therapy to others and would opt to choose this alternative to surgery. The satisfactory response rate suggests that demographic factors are not a determinant among patients regarding their perception for acquiring new knowledge. Patients with personal experience with RM had a more positive response when asked if it helps their condition and think it is very effective for OA or tendinitis and are comfortable recommending it to others. Whilst this positive attitude may lead to increase in number of patients who would prefer to undergo RM therapy, the effect may not be significant at this stage, due to the infancy of regenerative medicine clinical applications.23 Furthermore, most of regenerative medicine practices and stem cell therapies are yet to be approved for human diseases.24 Currently, there are a number of therapies being established and an increasing number of clinical trials being launched. As the field progresses, patients’ knowledge and perception of regenerative medicine may be directed to better disease management.25–27 Patients are an important target group for educational programs, and advanced understanding of stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine will educate them to undergo these treatments.28

Although our results show positive perceptions regarding regenerative medicine, many still have inadequate knowledge on the topic. Given the vulnerable state of some patients who seek regenerative and stem cell therapies, perhaps without the requisite knowledge for making informed decisions, there is increased potential for patient exploitation.26 Physicians must therefore be mindful of the ways in which at-risk or susceptible patients may process information and arrive at decisions about their treatment options, expectations, and ultimately, the potential for success.29 A promising way of navigating such difficult circumstances, where treatment options are uncertain or complex, is through the use of shared decision making, whereby the physician describes the risks and benefits of potential treatment options and the patient is given an opportunity to express preferences and values before collaboratively arriving at and evaluating treatment decisions. The process of obtaining informed consent and engaging in shared decision making with patients involves conveying information about the reasonable effectiveness of a proposed treatment, as well as its risks and benefits. This can be particularly difficult with respect to regenerative and stem cell therapies, as this is an area of medicine that currently lacks substantive data on efficacy.15,21,29 The lack of a formal mechanism for reporting outcomes of unproven stem cell interventions, both positive and negative, adds to the difficulty involved in generating data on the effectiveness of such interventions, as does the fact that there is neither a requirement, nor a mechanism, for reporting adverse events related to interventions administered outside of clinical trials and investigations.30 Thus, by the rapid advancement in all areas of regenerative medicine, the need for translational medicine to translate basic research to clinical practice by increasing patients’ knowledge and perception is obvious. The main purpose of knowledge translation is to ensure that there is adequate awareness, access and application of products of from evidence-based research among all levels of healthcare providers and consumers.1,22

Participants overall had a positive perception of their level of understanding and effectiveness of regenerative medicine. Our results showed that 70% of participants had a positive view of this treatment modality despite the fact literature does not support the effectiveness of this therapy. This shows how patients perceptions of regenerative medicine as an acceptable orthopedic treatment option for musculoskeletal issues. More research clearly needs to be dedicated to this area of medicine given the public interest and desire for these regenerative medicine treatments.

None.

Author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2020 Meiyappan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.