International Journal of

eISSN: 2381-1803

Research Article Volume 11 Issue 1

1Nucleus of Research in Exact and Technological Sciences, University of Franca, Brazil

2Department of Biology, Sciences and Letters of Ribeir

3Department of Chemistry, University of S

Correspondence: Eduardo J Crevelin, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters of Ribeir, Tel +55 16 3515 4856

Received: December 14, 2017 | Published: January 29, 2018

Citation: Aguiar GP, Lima KA, Severiano ME, et al. Antifungal activity of the essential oils of plectranthus neochilus (Lamiaceae) and tagetes erecta (Asteraceae) cultivated in brazil. Int J Complement Alt Med. 2018;11(1):31?35. DOI: 10.15406/ijcam.2018.11.00343

In this study, we report on the antifungal activity in vitro of the essential oils of Plectranthus neochilus and Tagetes erecta cultivated in Brazil against fungi that cause dermatomycoses and aspergillosis in terms of their minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC). Our results revealed that the essential oil of P. neochilus displays promising antifungal activity against R. stolonifera (MIC=125μg/mL). On the other hand, the essential oil of T. erecta demonstrated be inactive against the selected dermatophytes (MIC>,000μg/mL). These data suggest that the essential oil of P. neochilus could be a good alternative in the control of R. stolonifera, because there is a great interest in the use of natural antifungal compounds for the control of this fungus.

Keywords: antifungal activity, essential oil, plectranthus neochilus; tagetes erecta, human immunodeficiency virus, HIV

IA, invasive aspergillosis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PN-EO, essential oil of plectranthus neochilus; TE-EO, essential oil of tagetes erecta; GC-FID, gas chromatography with flame ionization; GC-MS, gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry; EI-MS, electron ionization mass spectrometry; RI, retention index; ATCC, american type culture collection; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MOPS, 3-(N-Morpholino)propanesulfonic acid; CFU, colony-forming unit

In recent years, the occurrence of clinical infections has increased dramatically. The considerable use of antifungal agents, there has been a remarkable increase in drug resistance among infections species.1 The diseases most common caused by fungi are dermatomycoses and aspergillosis, where the dermatomycoses result from superficial fungal infections of the skin, hair, or nails, which could affect the human health and quality of life2,3 not only in underdeveloped countries but also in elderly and immunocompromised patients worldwide.4 Over the years, the dermatomycosis has had a considerable increase, being that their treatment is still based on the use of triazoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole), imidazoles (ketoconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), and griseofulvin.5 However, due to the increase in the number of individuals immunocompromised by HIV, transplanted individuals and individuals undergoing cancer treatment, there was a reduction in the number of effective drugs against many dermatopathogens.6 In Brazil, human fungal infections are prevalent, but these diseases caused by fungi are not officially reportable.7 About 80% of the cases of infectious pneumonic mortality in immunocompromised patients are caused by invasive aspergillosis (IA), where the health problems caused by Aspergillus include allergic reactions, lung infections, and infections in other organs.8 Amphotericin is most frequently employed in conventional therapy, but its limited efficacy and poor patient tolerance to side effects culminates in response rates of only about 35% and high mortality.9 Although the synthetic fungicides are effective, the development of fungal resistance, toxicity to non-target organisms and environmental problems is due to its continuous or repeated application.10 The search for antifungal compounds from natural sources has increased over the last decade, and plants continue to be a major source of biologically active compounds that may provide lead structures for the development of new drugs.11 In this scenario, essential oils constitute a rich source of bioactive chemicals and have been recently pointed out as a promising alternative against the pathogenic fungi.12–15

The herbaceous and aromatic plant Plectranthus neochilus is popularly known as “boldo-rasteiro” in Brazil.16 The essential oil of P. neochilus displays antimicrobial,17 antischistosomal,16 and insecticidal,18 activities. On the other hand, Tagetes erecta L., commonly known as “marigold” in many countries and as “cravo-de-defunto” in Brazil, is an annual aromatic and branched herb native to Mexico. The essential oil from its leaves is utilized as antihelminthic in the Amazonia region.19 Despite the different reported biological activities of these plants, the antifungal effects of its essential oil have not yet been investigated. Thus, as part of our ongoing interest in the biological activities of essential oils, in this work, we now report the chemical composition and the antifungal activity in vitro against fungi that cause dermatomycoses and aspergillosis of the essential oils obtained from leaves of P. neochilus (PN-EO) and T. erecta (TE-EO) grown in Brazil.

Plant materials

Adult P. neochilus Schltr. (Lamiaceae) and T. erecta L. (Asteraceae) leaves were collected at “May 13th Farm” (20°26’S 47°27’W 977m) in May 2011. The collection site was located near the city of Franca, state of São Paulo, Brazil. These species were identified by Professor Dr. Milton Groppo, who received a voucher specimen each (SPFR 12323 for P. neochilus and SPFR10014 for T. erecta). Subsequently, these species were deposited at the Herbarium of the Department of Biology (Herbarium SPFR), University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Essential oil extraction

Fresh leaves of P. neochilus and T. erecta were submitted to hydrodistillation in a Clevenger-type apparatus for 3h. To this end, 1200g of the plant material was divided into three samples of 400g each, and 500mL of distilled water was added to each sample. Condensation of the steam followed by accumulation of the essential oil/water system in the graduated receiver of the apparatus separated the essential oil from the water, which allowed for further manual collection of the organic phase. Anhydrous sodium sulfate was used to remove traces of water. Samples were stored in an amber bottle and kept in the refrigerator at 4°C until analysis. Yields were calculated from the weight of the fresh leaves.

Gas Chromatography (GC-FID) analyses

The essential oil of P. neochilus (PN-EO) and T. erecta (TE-EO) were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) on a Hewlett-Packard G1530A 6890 gas chromatograph fitted with FID and a data-handling processor. An HP-5 (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) fused-silica capillary column (length=30m, i.d.=0.25mm, and film thickness=0.33𝜇m) was employed. The column temperature was programmed to rise from 60 to 240°C at 3°C/min and then held at 240°C for 5 min. The carrier gas was H2 at a flow rate of 1.0mL/min. The equipment was set to the injection mode; the injection volume was 0.1𝜇L (split ratio of 1:10). The injector and detector temperatures were 240 and 280°C, respectively. The relative concentrations of the components were obtained by peak area normalization (%). The relative areas were the average of triplicate GC-FID analyses.

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses

GC-MS analyses were carried out on a Shimadzu QP2010 Plus (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) system equipped with an AOC-20i autosampler. The column consisted of Rtx5MS (Restek Co., Bellefonte, PA, USA) fused-silica capillary (length=30m, i.d.=0.25mm, and film thickness=0.25𝜇m).The electron ionization mass spectrometry (EI-MS) mode at 70eV was employed. Helium (99.99%) at a constant flow of 1.0mL/min was the carrier gas. The injection volume was 0.1𝜇L (split ratio of 1:10). The injector and the ion source temperatures were set at 240 and 280°C, respectively. The oven temperature program was the same as the one used for GC-FID. The mass spectra were registered with a scan interval of 0.5 s in the mass range of 40 to 600 Da.

Identification of the PN-EO constituents

PN-EO and TE-EO compounds were identified on the basis of their retention indices relative to a homologous series of n-alkanes (C8-C20). To this end, an Rtx-5MS capillary column was employed under the same operating conditions as in the case of GC. The retention index (RI) of each constituent was determined as described previously.20 The chemical structures were computer-matched with the Wiley7, NIST08, and FFNSC1.2 spectral libraries of the GC-MS data system; their fragmentation patterns were compared with the literature data.21

Antifungal activity in vitro

Antifungal assays were performed using isolated Aspergillus fumigatus (JA13a) and Rhizopus stolonifer (JA08a) strains belonging to the fungus collection of the Department of Biology of the Faculty of Phylosophy, Sciences, and Letters of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo. Aspergillus brasiliensis (ATCC 16404) were also included in this experiment. The antifungal activity of the tested compounds against the fungi was evaluated in terms of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) according to protocol CLSI M38-A2.22 The PN-EO and TE-EO samples were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in buffered (0.165M of MOPS) RPMI 1640 medium (R8755) in order to obtain a concentration of 2mg/ml. The strain inoculums were suspended in 0.85% saline solution, to obtain concentrations of 1x105CFU/mL. Then, 100μl of the cell suspensions were added to 96-well microplates containing medium and 100μL of one of the previously prepared solutions of PN-EO and TE-EO to obtain spore concentrations of 5x104CFU/ml. The microplates were incubated in an orbital shaker apparatus at 30°C and 100rpm for seven days. The samples were evaluated at concentrations ranging of 500-0.244μg/ml. A resazurin (Sigma-Aldrich®) aqueous solution (0.02%) was employed to determine microorganism viability. In these assays, Ketoconazole (concentrations varying from 40 to 0.019μg/ml) was achieved as the positive control for these assays. All the assays were carried out in triplicate.

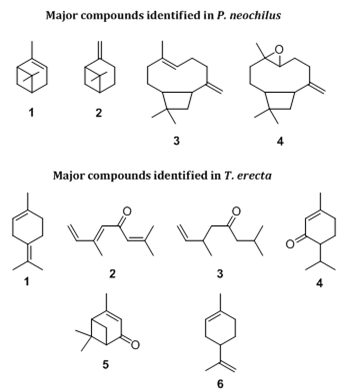

This work relied on minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values to evaluate the antifungal activity of the essential oils of P. neochilus (PN-EO) and T. erecta (TE-EO) against fungi that cause dermatomycoses and aspergillosis; Ketoconazole was used as positive control. Table 1 summarizes the MIC values. According to the literature, samples with MIC values lower than 100μg/mL, between 500 and 1,000μg/mL, and higher than 1,000μg/mL correspond to promising, moderate, and weak activities, respectively, whereas MIC values higher than 1000μg/mL denotes inactivity.23 In this context, PN-EO displayed weak activity against A. brasiliensis (MIC>2,000μg/mL) and A. fumigatus (MIC=2,000μg/mL), but it showed significant antifungal activity against R. stolonifera (MIC=125μg/mL). Hydrodistillation of P. neochilus leaves afforded PN-EO in 0.03%±0.01 (w/w) yields. Gas chromatography revealed the presence of 31 compounds and the major PN-EO constituents (Figure 1) were 𝛼-pinene (1; 14.1%), 𝛽-pinene (2; 7.1%), trans-caryophyllene (3; 29.8%), and caryophyllene oxide (4; 12.8%), as shown in Table 2. Abi-Ayad & co-workers24 reported the antifungal activity of Aleppo pine essential oil against A. flavus, A. niger, Fusarium oxysporum, and R. stolonifer. According to them, the antifungal activity was due to the presence of caryophyllene oxide with 52% of predominance in the essential oil. Our essential oil is characterized by the presence of important concentrations of trans-caryophyllene (29.8%), 𝛼-pinene (14.1%), and caryophyllene oxide (12.8%). Thus, the antifungal properties of this oil can be atrbuted to the content of these main components that likely act in a synergistic manner and their mutual interaction plays an important role in the overall activity of this essential oil. Moreover, caryophyllene_oxide is known for its use as preservative in foods, drugs, and cosmetics.24 and it is tested as an antifungal against dermatophytes in onychomycoses with significant results.25

On the other hand, TE-EO was inactive against all the assayed fungi with MIC values higher than 1,000μg/mL. The yield of TE-EO obtained by hydrodistillation was 0.36% (w/w fresh leaves). Gas chromatography revealed that monoterpenes (96.8%) are the main constituents (Figure 1) of TE-EO, being α-terpinolene (1; 17.9%), (E)-ocymenone (2; 12.9%), dihydrotagetone (3; 11.8%), piperitone (4; 8.8%), verbenone (5; 9.7%), and limonene (6; 10.4%) its major constituents (Table 3). Investigation of Stević et al.26 suggested that the low antifungal activity of essential oil of lemon, orange, and eucalyptus against twenty one fungi isolated from medicinal drugs can be explained by dominance of limonene, which is considered the weakest inhibitor of fungal growth among the pure monoterpene compounds.26 Our results suggest that limonene may act in an antagonistic manner between the constituents in TE-EO contributing to its low antifungal activity. Thus, the antifungal activity of essential oils appears to result from a combination of different molecules present in essential oils due to their several modes of action, which can increase membrane permeability, destroying the external membrane of the fungi,27,28 or lead to a decrease in the size of the fungi and thus a modification of their cell morphology.29

Figure 1 Chemical structures of the main chemical constituents identified in the essential oil of the leaves of P. neochilus and T. erecta.

Essential Oils |

A. Brasiliensis |

A. Fumigatus |

R. Stolonifer |

PN-EO |

> 2000μg/mL |

2000μg/mL |

125μg/mL |

TE-EO |

> 2000μg/mL |

1000μg/mL |

1000μg/mL |

Positive Control |

1.25 µg/ml |

1.25µg/ml |

2.50 µg/ml |

Table 1 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values (𝜇g/mL) obtained for the essential oil of P. neochilus (PN-EO) and T. erecta against selected fungi

xc |

RT [min]a |

RIexpb |

RIlitc |

Content [%]d |

Identificatione |

α-thujene |

5 |

921 |

924 |

6.3 |

RI, MS |

α-pinene (1) |

5.19 |

929 |

932 |

14.1 |

RI, MS |

thuja-2,4(10)-diene |

5.43 |

939 |

941 |

0.2 |

RI, MS |

camphene |

5.62 |

943 |

947 |

0.1 |

RI, MS |

sabinene |

6.21 |

966 |

971 |

1.9 |

RI, MS |

b-pinene (2) |

6.37 |

975 |

977 |

7.1 |

RI, MS |

b-myrcene |

6.65 |

985 |

988 |

0.3 |

RI, MS |

cctan-3-ol |

6.9 |

993 |

996 |

0.2 |

RI, MS |

α-terpinene |

7.53 |

1015 |

1016 |

0.5 |

RI, MS |

o-cimene |

7.79 |

1022 |

1023 |

0.3 |

RI, MS |

limonene |

7.94 |

1026 |

1027 |

0.2 |

RI, MS |

(Z)-b-ocymene |

8.14 |

1030 |

1033 |

0.4 |

RI, MS |

(E)-b-ocymene |

8.5 |

1040 |

1043 |

1.8 |

RI, MS |

g-terpinene |

8.94 |

1052 |

1055 |

1.4 |

RI, MS |

a-terpinolene |

9.94 |

1080 |

1084 |

0.2 |

RI, MS |

4-terpineol |

13.75 |

1177 |

1179 |

1.2 |

RI, MS |

α-cubebene |

20.78 |

1341 |

1344 |

0.5 |

RI, MS |

α-copaene |

21.97 |

1366 |

1372 |

1.2 |

RI, MS |

b-bourbonene |

22.29 |

1380 |

1379 |

1.1 |

RI, MS |

b-cubenene |

22.5 |

1378 |

1384 |

0.3 |

RI, MS |

trans-caryophyllene (3) |

23.8 |

1412 |

1415 |

29.8 |

RI, MS |

α-humulene |

25.25 |

1448 |

1450 |

1.5 |

RI, MS |

germacrene D |

26.3 |

1470 |

1476 |

6.2 |

RI, MS |

eremophilene |

27.51 |

1504 |

1505 |

3.9 |

RI, MS |

α-amorphene |

27.61 |

1506 |

1508 |

0.4 |

RI, MS |

d-cadinene |

27.83 |

1514 |

1513 |

1.9 |

RI, MS |

(E)-nerolidol |

29.63 |

1554 |

1559 |

0.3 |

RI, MS |

caryophyllene oxide (4) |

30.26 |

1571 |

1575 |

12.8 |

RI, MS |

unknown |

32.06 |

--- |

1622 |

0.3 |

RI, MS |

epi-α-cadinol |

32.62 |

1634 |

1637 |

1.5 |

RI, MS |

d-cadinol |

32.7 |

1636 |

1639 |

0.8 |

RI, MS |

α-cadinol |

33.12 |

1647 |

1650 |

1.3 |

RI, MS |

Monoterpenes hydrocarbons: |

35 |

||||

Oxygenated monoterpenes: |

1.2 |

||||

Sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons: |

46.8 |

||||

Oxygenated sesquiterpenes: |

16.7 |

||||

Not identified: |

|

|

|

0.3 |

|

Table 2 Chemical composition of the essential oil from the leaves of P. neochilus identified by GC-MS

aRT: Retention time determined on the Rtx-5MS capillary column.

bRIexp: Retention index determined relative to n-alkanes (C8–C20) on the Rtx-5MS column.

cRIlit: Retention index.

dCalculated from the peak area relative to the total peak area.

eRI, comparison of the retention index with the literature; 21 MS, comparison of the mass spectrum with the literature.

Chemical compound |

RT [min]a |

RIexpb |

RIlitc |

Content [%]d |

Identificatione |

α-pinene |

5.19 |

931 |

939 |

0.5 |

RI, MS |

camphene |

5.62 |

947 |

953 |

0.2 |

RI, MS |

sabinene |

6.2 |

971 |

976 |

0.9 |

RI, MS |

α-phellandrene |

7.2 |

1007 |

1005 |

0.5 |

RI, MS |

Limonene (6) |

7.94 |

1026 |

1027 |

10.4 |

RI, MS |

(Z)-b-ocymene |

8.13 |

1030 |

1033 |

4.2 |

RI, MS |

(E)-b-ocymene |

8.5 |

1040 |

1043 |

0.5 |

RI, MS |

Dihydrotagetone (3) |

8.69 |

1049 |

1054 |

11.8 |

RI, MS |

a-terpinolene (1) |

9.93 |

1080 |

1084 |

17.9 |

RI, MS |

linalool |

10.5 |

1100 |

1098 |

0.4 |

RI, MS |

1,3,8-p-mentatriene |

11 |

1112 |

1111 |

0.8 |

RI, MS |

(Z)-ocymene oxide |

11.65 |

1128 |

1128 |

0.6 |

RI, MS |

(E)-tagetone |

12.58 |

1151 |

1146 |

7 |

RI, MS |

linalool propionate |

14.38 |

1194 |

1174 |

0.6 |

RI, MS |

verbenone (5) |

15.9 |

1230 |

1218 |

9.7 |

RI, MS |

(E)-ocymenone (2) |

16.22 |

1238 |

1239 |

12.9 |

RI, MS |

piperitone (4) |

16.84 |

1252 |

1282 |

8.8 |

RI, MS |

piperitenone |

20.4 |

1335 |

1342 |

9.7 |

RI, MS |

trans-caryophyllene |

23.77 |

1414 |

1418 |

1.2 |

RI, MS |

precocene I |

25.6 |

1458 |

1467 |

1.4 |

RI, MS |

Monoterpenes hydrocarbons: |

35.9 |

||||

Oxygenated monoterpenes: |

60.9 |

||||

Sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons: |

2.6 |

||||

Others: |

|

|

|

|

0.6 |

Table 3 Chemical composition of the essential oil from the leaves of T. erecta identified by GC-MS

aRT: Retention time determined on the Rtx-5MS capillary column.

bRIexp: Retention index determined relative to n-alkanes (C8–C20) on the Rtx-5MS column.

cRIlit: Retention index.

dCalculated from the peak area relative to the total peak area.

eRI, comparison of the retention index with the literature;21 MS, comparison of the mass spectrum with the literature.

The results obtained from this study showed that the essential oil of P. neochilus (PN-EO) displays promising antifungal activity against R. stolonifera (MIC=125μg/mL). On the other hand, the essential oil of T. erecta (TE-EO) demonstrated be inactive against the selected dermatophytes (MIC>1,000μg/mL). Thus, our results suggest that PN-EO could be a good alternative in the control of R. stolonifera, because there is a great interest in the use of natural antifungal compounds for the control of fungi as R. stolonifera, which has importance in the postharvest agricultural system and food industry, and are also responsible for diseases in plants and humans as the parlous disease called zygomycosis in which fungal infection are seen in face and oropharyngeal cavity. This is the first report on the antifungal activity of the essential oils from the leaves of P. neochilus and T. erecta to date.

The authors are grateful to the Brazilian Foundations FAPESP (Proc. 2007/54241-8), for financial support. We would like to thank Professor Dr. Antonio Eduardo Miller Crotti by technical support.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2018 Aguiar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.