International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 6

Projeto Carnívoros, Instituto de Pesquisas Cananéia -IPeC, Brazil

Correspondence: Giovanne Ambrosio Ferreira, Instituto de Pesquisas Cananéia -IpeC, Rua Tristão Lobo 199 Centro, Cananéia, SP 11990-000, Brazil

Received: November 10, 2017 | Published: December 28, 2017

Citation: Ferreira GA. Wild neighbors: perception of residents of the environment of a fragment of atlantic forest in urban areas on the presence and approximation of coatis (Nasua nasua). Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2017;2(6):177-183. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2017.02.00039

Coatis (Nasua nasua) are often found in the forest areas, but are also adaptable to small urban fragments. This may represent disorders and problems with living with human populations. Here, we showed the residents' perceptions, recorded through questionnaires, about the coati's approximation to urban areas, in the margin of a remnant fragment of Atlantic forest. Of interviewees, 66.23% did not attribute the coati's visitation to risk or considerable problems. Among those interviewed 80.52% offered food to the animals. They have also reported the coatis exploiting solid waste deposits. We reported a few isolated cases involving negative interactions between coatis and humans or domestic animals. Although we verified a positive outlook by the population to this interaction, there are several risks arising from the approach of these animals. We need to develop environmental education strategies to the population close to the forest fragment, as well as in-depth studies to verify and reduce such risks.

Keywords: atlantic forest remnant, behavioral changes, food changes, interaction, questionnaires

Habitat destruction, fragmentation, and degradation, coupled with the intense pressure exerted by anthropic occupation on these remaining fragments, may result in an increasingly severe decline in the exploitation area of several wild species, forcing them to use new alternatives to get resources.1–6 However, in remnant fragments, some mammal species of the carnivorous order, because they do not present habitat preferences, it can be found often, thus presenting great mobility and ability to explore anthropized environments.7 Provided they are close to patches of native vegetation.8 Thus, contacts between humans, wild animals, and domestic animals have increased as humans advance over the habitats of wildlife, and wild animals are forced to use and live in the vicinity of these human settlements.9 The species Nasua nasua, popularly known as coatis, is found distributed throughout the Americas. However, the bibliographic record for the species is relatively scarce and recent, which makes the study of these animals of paramount importance.10 They are animals of habits mainly diurnal, scansorial and omnivores, displaying a generalist diet.10–16 In urban areas, they may eat remains of food deposited in dumps close to their area of activity or supplied by humans.16–20 Although they are not considered carnivores’ top chain, they are important not only in the role of controlling populations of small vertebrates and invertebrates but also act as seed dispersers.17,18,21,22 The species is highly prized as hunting and does not have a very high resistance to this type of anthropogenic pressure.2,23 The species is also impacted by hunting for retaliation and conflict. Lately, there have been a growing number of complaints about the coatis’ presence in condominiums and urban areas close to forest fragments.24 Coatis can cause injuries and bites to humans in situations where there is habituation caused by providing food to these animals.25 These wild animals, when they leave the forest in search of domestic food, can suffer possible behavioral changes. They are exposed to direct or indirect anthropogenic aggression. They can also act in the spread of zoonosis. This can occur either from wild to domestic species, or vice-versa.9

The interactions between wild nature and human beings are often studied through the questionnaires applied to the characters involved in these interactions, analyzing their visions, knowledge, and attitudes, thus orienting themselves to proper conservation and understanding proposals for different species in different situations.26–33 In this way, the present study aimed to analyze the environmental perception of the interviewees about the coatis' approximation to anthropic areas in an Atlantic Forest fragment in the urban center of Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais State. We use pre-structured questionnaires, to verify the problems possibility, caused by the approximation caused by this approximation, and by the food supply to the coatis.

Study area

The municipality of Juiz de Fora has a total area of 1,424km² and is located in the southeast of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, between 21º34’-22º05’S and 43º09’-43º45’W. Its minimum and maximum altitudes are 467m and 1104m, respectively. According to the Köppen climate classification, the municipality has Cwa and Cwb climates (highland tropical climate with hot summers). The average annual temperature is approximately 22.5ºC, and the average annual precipitation is 1470mm.34

The woodland fragment known as Morro do Imperador Forest is situated between coordinates 21°45’13”-21°46’13”S and 43°21’19”-43°22’15”W. It is an area consisting of a mosaic of fragments totaling 78 ha of secondary forest; Mata do Morro do Imperador reaches an altitude of 923m, one of the highest points in the city. According to Sato,35 this area is classified as Seasonal Semi-deciduous Mountain Forest, a subdivision of the biome Atlantic Forest. It is one of the remaining fragments of this type of woodland in Juiz de Fora, localized in a central area of the city that is comprised of private land as well as public areas belonging to the municipal government. We apply the procedures, which we will describe later, at seven sites in the area surrounding the forest fragment (Figure 1).

In the residences and establishments in the region surrounding Morro do Imperador Forest, we collected the data through the semi-structured questionnaires application.36 For the interviewees' sampling, we used the "snowball" methodology, which consists in the identification by the researcher of one or more individuals that could be interviewed and from these, were then named other people of the study site that, by chance could also be interviewed, following criteria previously established by the researcher Bernard HR.37 The choice of the first contacts to carry out the interviews was made actively, with the interviewees' approach in his residence or in areas close to this, based on his dwellings proximity with the forest remnant studied. In the approach, after a presentation by the researcher, a question was asked about which animal species sited near the residence. And based on these answers, when the person pointed the coatis' presence out, the interviewees were then invited to answer the questions in the questionnaire. In order to avoid having any influence on the answers given by the interviewees, we interviewed all informants separately. We determined the sample size when responses were similar, thus determining data saturation.38

The applications of the questionnaires occurred over six months. During this period, a follow-up along with some points of occurrence of the coatis’ visits was carried out, to confirm visits to the properties during the period of the survey. For such a weekly visit occurred for each study area. The interviews were guided by a standard semi-structured questionnaire39 containing 21 open and 14 closed questions that functioned as a roadmap for the interview. The interview was conducted in an informal manner following this questionnaire.40 However, some questions were not answered and the questionnaire could not be used as a roadmap on those two occasions. While some answers were noted on paper, other reports were digitally registered using a small MP3 recorder with the permission of those interviewed. Were later, this records transcribed and analyzed.41 All interviews were conducted through dialogues. This process facilitated interaction, establishing trust between interviewers and respondents. The questionnaire itself was divided into categories with questions focusing on:

After transcribing the interviews, a table was created to organize the data by categories related to the initial research questions of the questionnaire,42 i.e., socioeconomic profile of the interviewee, identification of local species, behavior of the animal, conflicts between people or pets and coatis, food supply to the coatis, disease transmission and identification of environmental problems in the reserve. This table allowed the reports to be classified by categories of themes so that the material contained on a particular topic could be easily identified, thus facilitating interpretation of the interviews.43 Generally, the interviewers continued conversing with the interviewees after the interviews. On many this occasion’s important information was thus acquired. Because in this moment was when the interviewees generally became visibly more comfortable and the interview less formal. The recordings made were analyzed on the same day of the interview, and questionnaires with missing data were completed and subsequently digitized into a database computer file. Descriptive statistics were conducted and the results present the averages and their respective standard deviation values.

Individual interviewed identification

In all, we approached 80 people, of whom 77 (86.52%) accepted to take part in the survey, responding to the questionnaire. Among the interviewees we had residents and merchants of the neighborhoods: Santa Helena (N=12), Paineiras (N=10), Vale do Ipê (N=11) and condominiums: Parque Imperial (N=10) and Chalés do Imperador =10); employees, teachers, high school students of the João XXIII Application College (N=11); as well as professionals responsible for surveillance and cleaning, as well as merchants from Gudesteu Mendes Square (N=13). Due to the interviewees’ heterogeneity, we gathered all these into a single group (Table 1).

Local |

N |

Gender |

Age Group |

Schooling |

|||||||

|

|

18-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

>55 |

e |

Hg |

Hgr |

||

1-Jardim Paineiras |

10 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

2-Gudesteu Mendes |

13 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

6 |

3-Santa Helena |

12 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

4-Chalés do Imperador |

10 |

8 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

5-João XXIII |

11 |

7 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

6-Parque Imperial |

10 |

8 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

7-Vale do Ipê |

11 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

Total |

77 |

50 |

27 |

27 |

18 |

11 |

13 |

8 |

15 |

37 |

25 |

Table 1 Number and profile in relation to the gender, age and schooling level of the interviewees, divided by area sampled, during the survey conducted in the region surrounding Morro do Imperador forest, Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil.

Identification of local species

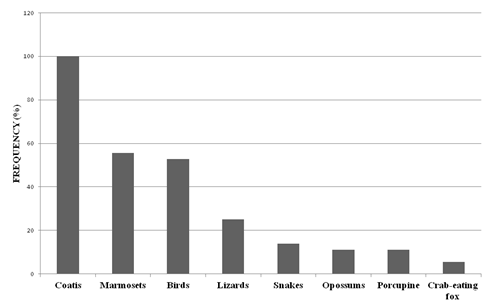

With the results of the interviews, we verified that some species of wild animals have frequently approached the urbanized areas of the studied region. Among the species most visualized near these areas, the coatis were reported by all the interviewees. In addition to coatis (100%), other species of mammals were also mentioned, such as: Marmoset (Callithrix sp) (68.83%), opossum (Didelphis aurita) (51.95%), porcupine (Coendou prehensilis) (28.57%); Crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) (8.88%), reptiles such as Tuoinambis lizards (Tupinambis merianae) (14.29%) and several species of snakes (unidentified) (12.99%); besides birds in general (74.55%). In a ranking that we established in relation to the sequence in which these animals were mentioned, we observed: 67.53% of the interviewees cited coatis first, 23.38% were cited as the second animal, and 6.49% placed third and 1.30% in the fourth and fifth position (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Frequency of occurrence of the species most visualized by the interviewees in the region surrounding the Morro do Imperador forest, Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil.

Characterize the behavior of coatis during the time they were sighted

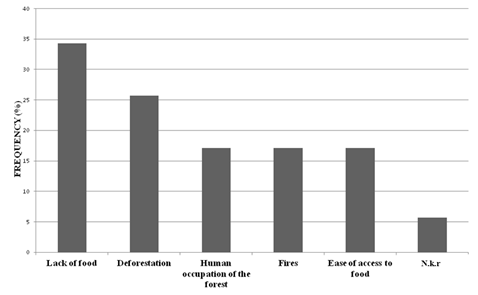

All the interviewees (100%) attributed the coati's approximation to residences in search of food. The reasons for this were mainly related to the lack of food resources available in the forest, followed by the constant processes of deforestation, anthropic occupation, and the burning of the area studied (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The motives mentioned by the interviewees about the approach of coatis food to urban areas in the area surrounding the Morro do Imperador forest, Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil. (N.k.r - did not know how to respond).

Food supply to the coatis (identifying the main items offered)

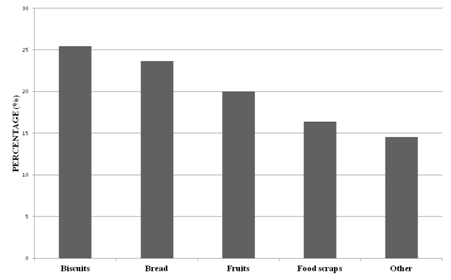

The results of the analyses made from the questionnaire responses showed that coatis were attracted by both the direct food supply (71.42% of respondents stated that they offered food to them), as well as indirectly, that is, exploring food residues found in trash cans 75.32% of those interviewed already witnessed this type of behavior) (Figure 4). Of the total number of people interviewed, 80.52% confirmed that, at least at some point, they have already provided food to coatis. Among the foods offered by the interviewees, cookies, bread, fruits, food rests and other types of food (such as salted, cakes and pet food) were recorded (Figure 5). Among those interviewed, 80.52% believe that the offer of undue food could cause some harm to the animal, and approximately 62.34% believe that it is not necessary to provide food to coatis, because according to them, the forest would give enough food.

Figure 4 Coatis in the region surrounding the Morro do Imperador forest, Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Above and left: Coatis interacting with children during recess at a college located near the forest fragment. In the picture, you can see some children offering cookies to the animals. In the image above and to the right: a coati on the bags containing coconut debris. This coming from a kiosk that sells coconut water on the banks of a highway that cuts the forest fragment. In the images below: it is possible to see coatis foraging in the trash.

Figure 5 Types of food offered to coatis by the interviewees in the region surrounding the Morro do Imperador forest, Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state, Brazil.

Negative interactions

Through the evaluations of the answers, it was found that 66.23% of the respondents do not care or do not attribute visits to coatis to any risk or considerable problems for humans. However, among the opponents, the main problems reported by these animals visitation were: possible cases of aggression (61.54%), food thefts, and the mess and dirt left after exploring the dumps (both 19.23% each). There were only two cases of aggression on the part of the coatis to humans: A fact occurred during the recess of the classes in the school where the questionnaire was applied, where according to the interviewee, the animal would have bitten one of the students while he offered food to a coati In another report, a coati would have entered a resident's home in the "Vale do Ipê" region and when trying to remove it the animal advanced against the person who tried to remove it, but this did not suffer a bite or much scratches. No case of predation to domestic animals in the region has been reported. However, 5.19% of respondents reported having seen coatis feeding on the ration that was offered to domestic dogs. And one interviewee reported the persecution, followed by the death of a coati by a group of street dogs. Also, no case involving the intentional killing of coatis by parts of humans (whether for sports hunting, feeding or retaliation) was found. Only sixteen respondents (20.78%) reported having seen dead animals killed in run-ins.

Disease transmission

Only 22.08% of the respondents answered that they believed in the disease transmission by the interaction with coatis. Among the diseases cited by these interviewees, 70.59% mentioned rabies, 23.52% cited yellow fever as possible diseases transmitted by coatis.

Identification Environmental problems in the forest reserve

The respondents pointed to the fire as the main problem regarding the reserve preservation (90.90%). Of respondents, 22.08% pointed to a highway that cuts the fragment as a problem, or potential threat to the animals that live in that reserve. Only 7.79% of the respondents said that the disorderly growth of the city, or irregular urban occupation, can also influence the conservation of this fragment and the species living there. The main measures proposed to minimize these problems were the following measures: the carrying out of educational campaigns and the increase in the Morro do Imperador’s forest preservation oversight; to build walls and loom access areas to the forest, making it impossible for the animals to contact the residences; not to feed the animals; transfer the animals to other preservation areas; among others. However, it was also pointed out by the interviewees that the problem would no longer be solved, while others proved to be extremely resistant to any measures that might prevent coati visitations to residences (Figure 6).

In this paper, we summarize data on a small number of local interviewed. This set of information is by no means a quantitative sampling or an estimate of all conflicts. However, we designated this data to contribute qualitatively. They are represented in the way the inhabitants see the conflicts between the coatis living in this remnant of the Atlantic forest under the great anthropogenic influence. The qualitative approaches based on reports of local members are appropriate for studies related to cultural perception of local residents.

The methodology that we adopted to obtain data from this study was shown to be effective. The application of the questionnaires in person, and their filling through informal conversations, at the same time as it values the presence of the researcher; it offers all possible perspectives for the informant to achieve the necessary freedom and spontaneity. In this way, this enriches the investigation, thus corroborating the statements of Triviños.44 The objective of these kinds of research is not to quantify, but to reduce the distance between subject and object, because studies of this kind are subjective and complex, and include elements of beliefs, symbols and concepts pre purchased the studied population.45 In qualitative studies such as ours, a large sample does not introduce new information related to the objectives of the research, which can become repetitive.46 With the high rates of degradation of the remaining fragment and due to the proximity of the residences, the presence of wild animals close to the urban environment in becoming increasingly common. Several studies report the use of areas inhabited by or close to those used by humans by different wild species, including coatis, as well as the use of human waste as a food source.16–22,47–51 Indirect analyses of fecal samples found at the observation sites, small fragments of Styrofoam, aluminum foil, and plastics. They also found remnants of domestic foods, such as fragments of cooked chicken bones, beans and fruit seeds used in human food, which demonstrates the weakness of these animals to these inappropriate foraging spaces for exploitation.16 And according to Sabbatini et al.49 and Guerrera et al.,52 the food supply by the inhabitants of the fragment can cause an alteration, both in the eating and behavioral habits, as metabolic disorders or possible pathology, mainly by ingestion of industrialized foods, with high levels of fat and sugars, and can cause serious health problems, as well as behavioral changes, as reported for other mammalian species. Although most respondents are aware that feeding these animals with these types of food may pose risks to their health, the incidence of this record is still noticeable, even though half of the respondents believe that it is not necessary to provide food for coatis.

There were few reports of the interviewees that involve some kind of direct aggression of the coatis on people. And although there was only a direct confrontation involving domestic animals and coatis in this study, the approximation of this species to anthropic areas increases the chances of these conflicts. This type of conflicts and aggressions possibility with domestic animals, mainly dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), can contribute to a potential in the propagation of diseases, including some zoonosis, several of them lethal. Some epidemiological studies show that several wild species, including not only the coati, but also other Procyonids, such as the hand-peeled (Procyon cancrivorus), may be involved in the cycle of transmission of diseases such as parvovirus and leishmaniasis.53 However, none of these species were identified by the interviewees as a possible disease transmitter. In contrast, in the United States, such as the ferret population (Mustela nigripes) was almost extinct due to canine distemper.54 There is also a record of the death of at least 25% of the lions (Panthera leo) in Serengeti National Park, associated with the same disease, contracted by dogs living near the reserve.54 Therefore, this approximation of coatis to anthropized environments deserves greater attention, dissemination, and clarification to the resident population near the forest, about the transmission of diseases possibility, whether from the wild to the anthropic environment, or the opposite.

According to studies by Scoss,55 the presence of roads in natural environments changes the way the area is used for many species of mammals. The road acts either as a corridor or as a barrier, attracting or repelling the mastofauna, which can lead to high rates of trampling of different species of mammals. Personal interviews and informal reports have shown that these are constant, since in some areas there are roads dividing the fragment of forest, and in certain points, the concentration of residences at opposite sides of the road, instigating the crossing of it. Coatis are eventually recorded in studies involving trampled fauna.24,56,57 However, we do not know the impact of this threat on its population as a whole. The observations obtained during the development of this work confirm the opportunistic behavior of coatis in the face of the use of alternative food resources that are in abundance and close to their area of activity, a fact that may be interfering with the demand for food inside the forest and possibly interfering with such as control of prey species or seed dispersal, as recorded for both coatis58 and other species of omnivorous carnivores, such as the crab-eating fox (C thous).48,59 In addition to all these losses for the animals mentioned above, we must add other negative factors, such as reducing the escape behavior for human species. This behavior presented naturally under natural conditions, where animals do not have intense contact with humans. The absence of such escape behavior may lead to both the capture and trafficking of wild animals; as well as a possible relation of dependence of the coatis towards humans, in the sense of acquiring of food, altering their natural behavior. Or, there is the possibility that this interaction may be favoring the population growth of this species since it lacks local natural predators.

Although a positive outlook has been verified on the part of the population in relation to this interaction, these food and behavioral changes registered for Nasua nasua, in this remnant fragment of the Atlantic Forest inserted in an urban environment, may possibly in the long term interfere with negative way on the network of interdependence in this ecosystem, thus reducing its ecological role in nature. We not verify if the forest provides sufficient food throughout the year to the entire population of coatis, justifying the search for other sources of food. The results obtained from this study reinforce that the implantation of mitigating actions are urgent and should be applied immediately, both for the preservation of coatis and other vertebrates, as well as in the attempt to reduce the problems of interactions between humans and wild animals.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Ferreira. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.