International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

1Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, United Kingdom

2Wildwood Trust, United Kingdom

Correspondence: Simon A Black, Durrell Institute for Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Wildwood Trust, United Kingdom, Tel +441227823144

Received: August 31, 2022 | Published: September 13, 2022

Citation: Amavassee EJ, Lee MAG, Ingram G, et al. Using the conservation excellence model to improve ecosystem restoration undertaken by organisations working in biodiversity hotspots. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2022;6(1):11-19. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2022.06.00178

Ecosystem restoration is a relatively new discipline in conservation biology and good practice is needed to close the knowledge-action gap to implement evidence-based conservation and effective landscape recovery. The Conservation Excellence Model (CEM) has been used to evaluate over 100 conservation organisations including programmes involved in reforestation and ecosystem renewal. This study evaluates a reforestation initiative in Mauritius using the CEM methodology and compares the programme’s organisation with an equivalent Indian Ocean Island programme in Comoros. This study aims to identify whether improvements in reforestation can be identified by CEM evaluation, whether recommendations for these specific reforestation programmes generate learning about effective practices in the sector, and whether the CEM is a relevant tool for comparing effectiveness of reforestation initiatives. The Mauritius programme is shown to utilise sound approaches, whilst being a relatively new organisation (with a profile of more than 350 points), yet can still make improvements already implemented and observed in its Comorian equivalent, which will enable significant improvement in approach and results in the future. The findings identify the importance of addressing threats and factors influencing ecosystem degradation, ensuring links between agricultural and reforestation goals, involvement of local communities, resilient management teams, and having teams based on local staff. CEM assessment provides a rapid, low-intensity approach to investigate connections and facilitate improvements in organisational practice, enhance conservation and restoration work, and enable a more purposeful effort to ensure advances in achievement, outcomes and impact of reforestation initiatives.

Keywords: ecosystem restoration; biodiversity conservation; performance evaluation; benchmarking; improvement; biodiversity hotspots; conservation excellence model

The science and practice of ecosystem restoration have never been more relevant and crucial in the Anthropocene for conserving Earth’s biodiversity, securing life-giving ecosystem services, increasing resilience to disasters, achieving food security, and adapting to climate change.1–3 In addition to these ecological impacts, ecosystem restoration, when implemented effectively with other coherent related policies, offers a pluralistic and holistic potential to ameliorate economic growth, human well-being, and environmental stewardship; all significant in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and Aichi Biodiversity Targets.4,2 In recognition of such critical social-ecological roles, the United Nations (UN) declared 2021-2030 as the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, a global impetus to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of all kinds of ecosystems. The success of these activities is dependent on conservation organisations' capacity to effectively and efficiently implement large-scale, high-quality, and ecologically-sound ecosystem restoration projects, and to engage with relevant partners and stakeholders.5 Unfortunately, around the globe, ecosystem degradation is known to negatively impact at least 1 to 6 billion hectares of land and 3.2 billion people representing an economic loss of more than 10.4% of annual global gross domestic product (GDP) through the loss of ecosystem services and biodiversity.6–8

The field of ecosystem restoration, a relatively young science, has experienced tremendous advancement over the past three decades owing to the worsening worldwide trends in ecosystem degradation.9,10 The Society of Ecological Restoration (SER) defines ecosystem restoration as ‘the process of assisting the recovery of a degraded, damaged or destroyed ecosystem’ at the scale required, using the best available science and traditional knowledge to secure a trajectory towards full recovery from an appropriate local native reference ecosystem.11 Thus, the ultimate goal of ecosystem restoration is to establish a self-sustaining ecosystem that is resilient to perturbations.12 However, in the short term, it is virtually impossible to measure the self-sustainability or success of an ecosystem undergoing restoration as the former requires years, decades, or even centuries to achieve full or partial recovery.13 For instance, it has been estimated that it would take at least 50 years to fully recover a cleared or highly degraded forest in the tropics31. Furthermore, in the past, several restoration projects have failed or underperformed since ecosystem restoration is a complex, long-term, energy-consuming, expensive undertaking, and multidisciplinary process.14,15 Therefore, adhering to standardized principles (e.g., International Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration), best-practice guidelines, continued monitoring (e.g., Five-star Recovery Wheel System) and an adaptive management approach (e.g., System Thinking) can ensure better performance, impact, and success.11,15

The recognition that recovery is a slow process should primarily encourage conservation organisations to adopt the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration as a launchpad to incentivize better establishment of restoration goals, adopt best practices and international standards, demand smarter monitoring and better accountability, and conduct further research and analysis to assess restoration effectiveness for designing and implementing more successful projects in the future, that are also characterised by better integration among society, practitioners, and scientists.16–18 Moreover, there is a critical need to prioritise the assessment of conservation organisations strategically implementing ecosystem restoration projects in recognised at-risk ecosystems, such as biodiversity hotspots, given their disproportionate importance to global species protection and conservation.19,20 Additionally,10 it is recognised that knowledge transfer between Small Island Developing States (SIDS) plays a significant role in informing restoration science and guiding evidence-based ecosystem restoration projects in these developing island nations. The value of ecosystem restoration will be greatest in SIDS where terrestrial habitats and biodiversity were destroyed at catastrophic levels from increasing anthropogenic pressure,10,21 resulting in unprecedented levels of species extinction and deforestation as has been experienced on many islands. For example, Mauritius has less than 2% of good quality forests left,22 while the Comoros archipelago has the fourth highest annual deforestation rate (5.8%) worldwide.23 Unfortunately, ecosystem degradation in developing countries is predicted to be the most rapid worldwide24 and often where resources are least available or allocated for biodiversity conservation and restoration.19

One key barrier to maximizing the scope and effectiveness of ecosystem restoration is the ‘organisation-practice gap’,25 where organisational assessment is not effectively integrated with restoration practice. This integration is defined here as the process of improving the effectiveness and performance of conservation organisations at implementing restoration projects.25 While tremendous efforts from the Society of Ecological Restoration provided an important stepping stone to distil key principles and concepts that underpin successful project design, planning, implementation, and monitoring, little has been done in improving our understanding of organisational effectiveness and performance in ecosystem restoration. Improvements in the practice of ecosystem restoration will originate at the level of individual conservation organisations.11 To meet the aspirations of the UN Decade, amplify the work of ecosystem restoration, and maximize funding investment from future restoration efforts, a comprehensive sector-specific evaluation model is required to provide a better understanding of the factors that enhance restoration success. Thus, for this study, the Conservation Excellence Model (CEM) will be used to assess the performance and effectiveness of two conservation organisations implementing ecosystem restoration in developing SIDS – Mauritius and Comoros. Furthermore, a comparison will be undertaken between the two organisations to formulate cost-effective improvement recommendations.

The CEM, derived from established business evaluation models, was developed to improve the performance and effectiveness of conservation organisations irrespective of their stages of development, size, and focus.26,27 The CEM uses a non-prescriptive and systems-thinking approach by incorporating aspects of management, human resources, culture, biodiversity, and impacts into the context of wider ecological and social systems.25,27 The nine-box framework model of the CEM (Figure 1) includes five “Approach” and four “Results” criteria, and the links between each.26 The “Approach” criteria are used to assess both technical conservation and generic management activities carried out to achieve the organisational purpose: Leadership, Policy & Strategy, People & Community Management, Resource Management, and Core Conservation Processes.26 The “Results” criteria cover the performance outcomes of the organisation: Biodiversity Results, People & Local Community Results, Impact on Wider Society, and Conservation Programme Results.26 The overall model emphasises the links between the organisation’s purpose, processes, people, and performance to encourage effective management with an adaptive approach from continuous learning, feedback, results, and outcomes;27,28 thus making the CEM an excellent example of an evidence-based approach to improving the effectiveness of organisations implementing ecosystem restoration.25

Figure 1 Schematic of the Conservation Excellence Model26 with the five Enablers or “Approach” criteria (left) and four Outcome or “Result” criteria (right). The criteria boxes are categorised by colour with those relating to People (White), Process (Black) and Performance (Grey).

The specific research aims of this study are to:

The CEM assessment methodology involves a three-step approach: (1) collecting data from the organisation under assessment; (2) reviewing and assessing collected data against the nine criteria; and (3) scoring each criterion twice.26 The scoring process is a standard approach that allows organisations to be benchmarked and compared; thus offering one of the best-suited and rapid frameworks to identify best practices, facilitate learning and knowledge management, enable greater role clarity as well as recommend the improvements needed in the restoration sector to achieve the best long-term outcomes.25 From applied experience,27 the CEM is regarded as a practical and affordable evaluation tool for resource-constrained conservation organisations – like the two organisations being assessed. To date, a wide range of conservation organisations across the globe, including those involved in ecosystem restoration and species recovery in tropical regions, have been assessed using the CEM.26,27,29

Data collection

Mauritius: Assessment was conducted by a remote, non-visiting assessor by using existing data taken from annual reports, action plans, daily work schedules, budget spreadsheets, website information, photographs, volunteer databases, and booklets on restoration strategies developed by the organisation. In addition, two structured interviews (Table 1) were conducted online with two key personnel – the project coordinator and the main fieldworker – focusing on the organisation as a whole and the ecosystem restoration project. A case study was developed by collating the collected data and interviews. The case study summarised the ‘Approach’ and ‘Results’ of the organisation against the 9 CEM criteria; enabling the provision of scores, identification of strengths, limitations, and recommendations for the organisation and project. For this case, an independent 9-criteria scoring process was conducted by the lead remote assessor (RA) and two independent assessors (IA), all trained on the CEM.

Criteria |

Sub-criteria |

1. Leadership |

a) Demonstrates commitment to biodiversity conservation |

How do leaders credibly show this? |

|

b) Support for conservation through resources/assistance |

|

Do financial resources, people and priorities reflect this commitment? |

|

c) Involvement with wildlife, stakeholders and other organisations. |

|

Are leaders visible in relevant activities within the program? |

|

d) Recognize/appreciate people’s efforts & achievements |

|

How do leaders encourage involvement, commitment and ideas? |

|

2. Policy and Strategy |

a) How policy, strategy and plans are based on relevant & comprehensive information |

Is there a scientific basis for plans and consideration of practical constraints? |

|

b) How policy, strategy and plans are developed |

|

Who is involved and how is information incorporated into strategy decisions? |

|

c) How policy, strategy and plans are communicated and implemented |

|

How do leaders make sure that relevant people know about objectives and plans? |

|

d) How policy, strategy and plans are regularly updated and improved |

|

When are plans reviewed and changed based on new data and knowledge? |

|

3. People & Community Management |

a) How people resources are planned and improved (workers, volunteers, community) |

What provisions are made for project teams, experts and community teams/volunteers? |

|

b) How people’s capacity is sustained and developed |

|

Are training/education plans and processes in place and is progress measured? |

|

c) How do people agree on targets and review performance |

|

Are targets set for the project team or the community and is this monitored? |

|

d) How people are involved, empowered/recognized |

|

How are roles/authorities assigned? Are decisions made locally (inc. ownership/land rights)? |

|

e) How people & programs have effective dialogue |

|

What communication & decision-making processes exist? How are they managed? |

|

f) How the well-being of people is managed |

|

How is the well-being of staff and community planned, monitored and accounted for? |

|

4. Resource management (inc Finance) |

a) Financial resource management |

How are finances managed (budgets, bank accounts, records, authorization, reports)? |

|

b) Information management: access, structures, validity, security |

|

How is data (scientific, management, financial) validated, stored, shared, and updated? |

|

c) Supplier and materials management |

|

How are suitable materials purchased & stored (supplier selection, contracts, inventory) |

|

d) Buildings, equipment and asset management |

|

How are buildings & equipment obtained and maintained to give value to the program? |

|

e) Intellectual property |

|

Is relevant information utilized and protected? |

|

5. Core Conservation Processes |

a) How core processes are identified |

Which approaches/techniques and why? Is there a scientific/research basis for these choices? |

|

b) How core processes are systematically managed, responsibilities are carried out |

|

Who is responsible? Are resources allocated? Are processes monitored and validated? |

|

c) How core processes are reviewed |

|

Are there reviews of technical results and management action (adaptive management)? |

|

d) How core processes are improved using innovation & creativity |

|

Are improvements undertaken including using new scientific knowledge/findings? |

|

e) How processes are changed and evaluated |

|

Are changes managed carefully, and results monitored and evaluated for improvement? |

|

6. Biodiversity Results |

a) Indicators of the response of biodiversity systems to conservation activity |

Habitat and population recovery, range, productivity, communities, richness |

|

b) Other measures: ecosystem function (e.g. water catchment), geophysical (e.g. erosion) |

|

7. People and Community Results |

a) Perceptions of the program (e.g. via surveys): support, interest, ownership of issues |

b) Other measures (staff turnover, levels of community involvement, conflict) |

|

The level of support (or conflict) is there in terms of measurable numbers |

|

8. Impact on Wider Society |

a) Perception of wider society (e.g. surveys) on the program, its objectives, awareness etc. |

b) Other indirect measures (public profile, support, donations, volunteers, press, concern) |

|

9. Conservation Program Results |

a) Financial measures of success (income /funding and investment/utilization) |

Performance against budget, investments, ratios |

|

b) Non-financial measures (project-related measures, e.g. objectives completed, milestones) |

Table 1 Interview questions based on sub-criteria of the Conservation Excellence Model

Comoros: Document review was conducted by assessing previous organisational assessments. No site visits, interviews, and scoring were needed to develop the case study. In 2014, a baseline CEM assessment was conducted from written documents, interviews with staff, site visits, and online materials; following which its senior managers used the recommendations to make major organisational improvements. After 3 years, in 2017, a CEM re-assessment was carried out and summarised in a case study. The 2017 CEM re-assessment report was provided by a third party and will be used as a second case study. Here, the scores were based on consensus between one assessor affiliated with the organisation and two independent assessors.

Scoring process

Qualified independent assessors (whose assessments have been calibrated in an approved CEM training workshop and who had experience of two or more organisational CEM evaluations) were involved in the scoring process. The scoring system was based on weighted on a scale from 0 to 100 to all 9 criteria.; each criterion being rated twice, that is, the five “Approach” criteria were reviewed for their ‘Approach’ and ‘Deployment’; and the four “Results” criteria reviewed both for excellence of ‘Results’ and ‘Scope’ scores (Table 2). Averages of all the individual scores allocated for each criterion by the assessors were calculated and used as the final criterion scores. Following, standard CEM protocols16 each mean criterion score was multiplied by a weighting of 1, 0.8, 0.9, 0.9, 1.4, 2, 0.9, 0.6, and 1.5 for criteria 1 to 9 respectively, defining a final CEM score as the sum of the 9 weighted scores out of 1000 points. The overall CEM score is used to benchmark with other organisations. For instance, an organisation scoring 500 points is considered a good-performing organisation with effective management, whereas an immature or ineffective organisation would score below 250 points. World class organisations score above 750 points.30 To avoid biases, none of the independent assessors were affiliated or connected to the two organisations.

Approach |

Score |

Deployment |

Score |

Overall |

· Anecdotal or non-value adding |

0% |

Little effective usage |

0% |

|

· Some evidence of soundly based approaches |

25% |

Applied to about one quarter of the potential when considering all relevant areas/activities |

25% |

|

· Evidence of soundly based systematic approaches and prevention-based systems. |

50% |

Applied to about one half of the potential when considering all relevant areas |

50% |

|

· Integration into normal operations and planning is well established |

|

|||

· Clear evidence of soundly based systematic approaches and prevention-based systems. |

75% |

Applied to about three quarters of the potential when considering all relevant areas |

75% |

|

· Clear evidence of refinement and improved effectiveness through check/review cycles. |

|

|

||

· Good integration of approach into normal operations and planning |

|

|||

· Clear evidence of soundly based systematic approaches and prevention-based systems. |

100% |

Applied to full potential when considering all relevant areas |

100% |

|

· Clear evidence of refinement and improved effectiveness through check/review cycles. |

|

|

||

· Total integration of approach into normal operations, planning and working patterns |

|

|||

Results |

Scope |

Overall |

||

· Anecdotal |

0% |

Results address few relevant areas/activities |

0% |

|

· Some results show positive trends* and/or satisfactory performance |

25% |

Results address some (~1/4) relevant areas & activities |

25% |

|

· Many results show strongly positive trends and/or sustained good performance over at least five cycles* (years) |

50% |

Results address many (~1/2) relevant areas & activities |

50% |

|

· Most results show strongly positive trends and/or sustained excellent performance over at least ten cycles (years) |

75% |

Results address most (~3/4) relevant areas & activities |

75% |

|

· Capability of processes appears to be improving |

|

|||

· Improvements appear linked to changes made by program |

|

|||

· Strongly positive trends and/or sustained performance in all areas over at least twenty cycles (years) |

100% |

Results address all relevant areas and facets of the program |

100% |

|

· Best in class in many areas of activity |

|

|||

· Improvements clearly linked to changes implemented by the program |

|

|||

· Indications that a sustained improved position will be maintained |

||||

Case study evaluation

Since the Mauritius case study was based on remotely gathered desk-based material (developed from organisational documents and interview material), the assessment document itself needed to be validated. To evaluate the quality of the Mauritius case study, a copy was submitted to a diverse sample of qualified and experienced CEM assessors from across the globe. Eighteen assessors from six continents (North America, South America, Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia) participated in the survey and were a fair representation of qualified CEM assessors (Figure 2). Participants responded by giving ratings (1–5) and feedback on three questions:

Assessment of the quality and validity of the Mauritius case study

Evaluations from the eighteen assessors involved in the survey, gave the case study an average rating overall from ‘valuable’ to ‘very valuable’ (Figure 3). Based on the expertise of the assessors, this evaluation confirms that the desk-based case study document was a valid source of information to conduct a fair and accurate assessment of the Mauritian programme.

Mauritius case study assessment

The organisation was established in 1989 and has been active in the field of restoration ecology since 2015. It specialises in the restoration of degraded landscapes and aims to restore a dry forest ecosystem on Small Mountain (Petite-Montagne) using an inclusive Ecosystem-based Approach (EbA) and raising awareness with the Biodiversity and Environment Education (BEE) Programme. The organisation and the restoration project are worthy of consideration for the CEM assessment having shown exemplary use of evidence-based practices in this emerging sector. This section will provide an overview of the CEM scores, strengths and areas of improvement for the organisation and its projects (Table 3).

Criteria |

A / R |

D / S |

Overall Scores |

Weightings |

Weighted Scores |

Leadership |

35 |

32 |

33 |

1 |

33 |

Policy & Strategy |

31 |

38 |

34 |

0.8 |

27 |

People & Community Management |

23 |

23 |

21 |

0.9 |

19 |

Resource Management |

47 |

55 |

51 |

0.9 |

46 |

Core Conservation Processes |

63 |

58 |

61 |

1.4 |

85 |

Biodiversity Results |

35 |

38 |

37 |

2 |

73 |

People & Local Community Results |

28 |

38 |

33 |

0.9 |

29 |

Impact on Wider Society |

20 |

27 |

23 |

0.6 |

14 |

Conservation Programme Results |

28 |

37 |

32 |

1.5 |

49 |

CEM SCORE out of 1000 |

376 |

Table 3 CEM score profile (Weighted scores) for the Mauritian programme in 2022

According to the CEM, a score of 376 out of 1000 places the organisation in a position of a good and maturing organisation. The organisation obtained high scores (out of 100) for core conservation processes (85%) and biodiversity results (73%) while the lowest scores are leadership (33%), people and community management (19%) and impact on wider society (14%).

A / R – Approach/Results; D / S – Deployment/Scope

Context and results showed that the organisation sustained good performance over a cycle of 5 years, that is, since 2015. For instance, the organisation used a classification system to virtually reconstruct the original vegetation of the site, determined suitable species for reintroduction, understood key ecosystem processes before degradation and identified all risks and threats to the project. Threats – fire and invasive species – are mitigated and controlled due to evidence of a high survival rate of planted reintroduced native species which is at 80% and a significant decrease in the total surface area burnt during wildfires. Of 87 species planted 71% are IUCN red-listed indicating the biodiversity value of the work. The impacts on society are limited in scope, however, the project was highly visible in the media and several corporate groups are interested in partnering with the organisation. As for programme results, targets are being achieved as per the project plan and are on track to reach the 11 hectares goal. The project is sustainable financially for the coming years with a rolling plan. In terms of people and local community results, on-site management is effective as staff are loyal and keen to take on more responsibilities if needed. The project leadership has a hands-on approach and allows staff to participate in decision-making.

Policies and strategies were aimed at using scientific knowledge to develop the project’s purpose, aims and goals to address habitat degradation at the project site. There is a clear rationale behind the selection of the conservation processes – restoration, threat mitigation and education – and the techniques are appropriate for the activities of the programme. There is a monitoring system in place and the results are used to know species adaptability and inform actions needed to reach the target ecosystem. The educational process is tailored to the needs of various groups. People and resources assessment identifies that the project staff are highly skilled, staff have a high level of trust and responsibility and have access to training. Finally, the leadership team is committed to getting the work done, has earned the trust of field workers and supports the learning and improvement of the individual staff members while actively engaging with other stakeholders

Comoros case study assessment

The organisation was officially founded in 2013 and aims to create sustainable and productive landscapes within Comorian communities by implementing projects to restore degraded lands and forests, preserving rivers and marine ecosystems while improving the living conditions of people. The 2014 CEM assessment concluded that the organisation was good and competent at its early stage of development with an overall CEM score of 389 out of 1000. This section summarises actions undertaken by the organisation following its first CEM assessment to implement recommendations for its natural resource management – reforestation project – and the organisation as a whole after the second CEM assessment at the start of 2017 (Table 4).

A / R – Approach/Results; D / S – Deployment/Scope

Criteria |

A / R |

D / S |

Overall Scores |

Weightings |

Weighted Scores |

2014 scores |

Leadership |

58 |

60 |

59 |

1 |

59 |

61 |

Policy & Strategy |

55 |

65 |

60 |

0.8 |

48 |

40 |

People & Community Management |

55 |

70 |

62 |

0.9 |

56 |

43 |

Resource Management |

50 |

70 |

60 |

0.9 |

54 |

32 |

Core Conservation Processes |

52 |

60 |

56 |

1.4 |

78 |

55 |

Biodiversity Results |

42 |

42 |

42 |

2 |

84 |

44 |

People & Local Community Results |

55 |

72 |

68 |

0.9 |

61 |

65 |

Impact on Wider Society |

50 |

62 |

56 |

0.6 |

34 |

32 |

Conservation Programme Results |

38 |

55 |

46 |

1.5 |

69 |

18 |

CEM SCORES out of 1000 |

543 |

389 |

Table 4 CEM profile (weighted scores) for the Comorian programme in 2017 and 2014 (last column)

Context data and results indicate a significant improvement from 2014. For instance, the organisation has developed its first 5-year strategic plan (2015 to 2020) clearly describing a ‘Theory of Change’, planted about 10,000 trees on 100 hectares of land for its reforestation work to improve watersheds around focal villages, and secured an agreement with landowners to protect Livingstone’s fruit bat roost sites. In terms of conservation programme results (69%), the organisation has adopted a multi-year funding model securing sufficient funds for the next few years, published its landscape approach as best practice on Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), and established community-based long-term forest restoration with plans to implement projects in three islands, delivered educational and agricultural programmes in villages and completed surveys to monitor forest health. Moreover, the organisation has developed a suite of indicators and communication strategies to measure its impact on society (34 %) nationally. However, there is a need to improve ‘People and Local Community Results’ (61%) by monitoring changes in poverty levels before and after interventions, building the capacity of the ecological team and planning succession to more from the ex-pat-led model.

The program’s strategy (48%) has addressed several issues raised in the context data by establishing a participatory approach to developing the multi-year strategic plan and involving the active input of village committees to provide feedback, improve communication and determine the level of impact of all interventions. Core conservation processes were predominantly restricted to research in 2014 (55%), but improved in 2017 (78%), and the organisation refined its agricultural interventions and improved the quality of its support to villagers through several studies. For instance, determining the most income-generating crops for communities to grow. Additionally, studies were completed to protect important fruit bat roost sites, develop an action plan for the mongoose lemur and devise a participatory monitoring system to identify indicator species.

A review of people and resource management (56%) in the organisation suggests that strong improvements were made particularly with control of financial processes. For instance, accounting software (a cash-flow management system) being used to track income and expenditure. The organisation has also developed new partnerships and strengthened existing ones with 6 international organisations and government bodies. Since 2014, there was a high degree of reliance on expatriate staff to lead the development of the organisation. After restructuring the organisation, roles were clarified, and local staff were trained and promoted to senior roles. For instance, training was provided to a few senior managers on statistical analyses and fundraising. Moreover, a transparent system was instituted for salary payments, staff well-being, health coverage and other additional incentives. In addition, regular management team meetings were significant during decision-making and staff were comfortable with challenging processes, suggesting improvements and discussing failures.

Leadership (59%) is effective, though considered vulnerable as it relied too heavily on a small group of individuals at the top of the organisation. Therefore, a new management structure was adopted delegating responsibilities to other team members. There was already a strong sense of pride, integrity and good governance. The organisation has established a clear appraisal system to monitor employees' performance and recognise success twice a year.

Comparison of organisational excellence in ecosystem restoration

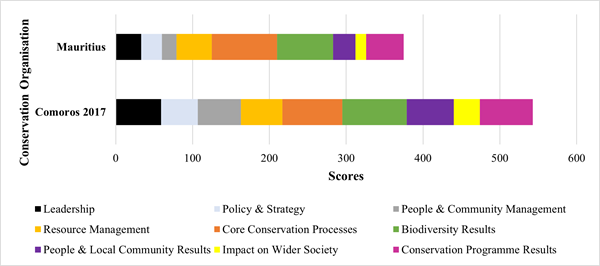

The CEM score (376 points) for the Mauritian organisation is compared with the 2014 baseline Comorian CEM performance (389 points) as shown in Figure 4, demonstrating similar baseline profiles points, both indicating a sound status in these relatively young organisations.

Figure 4 Profiles showing the comparison between baseline CEM scores of the Mauritian reforestation organisation with the first 2014 assessment of the Comorian reforestation organisation.

The second assessment of the Comorian organisation in 2017 saw its score increase by 39.6% after the organisation implemented the 2014 recommendations for improvement. The 2017 CEM scores are compared with baseline scores of the Mauritian organisation (Figure 5). The impact of the CEM assessment is outstanding, as the Comorian organisation’s performance can be regarded as a breakthrough in the conservation sector (> 500 points). Additionally, this suggests that the Mauritian organisation’s performance can improve from feedback provided through the case study document.

Figure 5 Profiles showing the comparison between baseline CEM scores of the Mauritian reforestation organisation with the second 2017 assessment of the improved Comorian reforestation organisation.

Recommendations

Mauritius: Livestock encroachment (i.e., goats getting onto the landscape) remains a problem and can reverse the success trend achieved to date. There is a need to develop appropriate cost-effective strategies to limit encroachment completely and by prioritising funds to fence the area completely in the form of a protected conservation management area (CMA). The monitoring of indicator species is not clear and the organisation need to seek assistance to develop appropriate surveys to monitor biodiversity recovery. There is also a Poor level of support from communities living near the project site. Surveys are needed to evaluate the perception and opinion about the public’s support of the project. Feedback surveys should be implemented to evaluate volunteers' satisfaction after activities.

Comoros: A significant proportion of conservation and ecological works were yet to be realised to a greater extent. Thus, the organisation needs to focus on capacity building by collaborating with experienced field ecologists or institutions to develop local capacity on ecological techniques and spearhead the species-monitoring work which needs to be integrated into the reforestation work.

Mauritius: Policies and strategies are underdeveloped in the organisation. Develop a process and strategy for empowering local communities to self-manage nurseries and plantations.

Comoros: A good amount of work was prioritised to develop and improve sustainable farming practices at the village level while links with ecological goals were in deficit. Therefore, it is important to develop biodiversity monitoring processes at the village level and demonstrate how agricultural improvement will positively impact biodiversity conservation and better livelihood.

Mauritius: Improve the direct ongoing engagement of communities with restoration activities, ongoing training, and support local capacity to develop a local ‘ownership’ of the project.

Comoros: Various agricultural interventions and conservation-related works are being carried out simultaneously. The organisation should develop an appropriate monitoring and evaluation system to track these processes and their linkages to provide evidence of improved conservation outcomes.

Mauritius: Seek new partnerships within the conservation and reforestation and ‘green economy’ sectors to access expertise, opportunities, and funding streams.

Comoros: There was a strong dependence on expatriate staff. With the change in management structure, refinement of roles, communication and culture, it is necessary that the new top management has access to the same existing or potential funders to discuss and share ideas over new projects that were accessible to the previous management team.

Mauritius: Restructuring the whole management team and organisation with a clear purpose, vision, goals, clarity of roles, good governance and leadership styles.

Comoros: New resilient senior management team has been established. The organisation needs to focus on developing leadership down and across the field teams and into the villages by focusing on knowledge transfer management or ‘Train the Trainers’ workshops.

The CEM assessment provides a rapid, low-intensity assessment approach to generating authentic scores across 9-criteria and is a suitable framework to investigate connections between organisational practices, specific conservation intervention work and the outcomes and impact achieved as a result. Therefore, it appears well suited for the assessment and comparison of multiple studies across a wide geographic, cultural and environmental scope, and can support increased collaboration and information-sharing within the sector to assist in improvement in effectiveness.25 Additionally, organisations managing multiple programmes can use the CEM as a reference for the evaluation of each programme in their portfolio to compare and contrast the reasons for relative successes in programmes. A further important consideration concerns the fact that while ecosystem recovery may take decades to complete, many conservation programmes themselves are relatively transient, perhaps 2–5 years in duration, so suitable exit strategies to establish sustainable work required beyond the remit of the programme must be considered as part of the evaluation of the current programme.29 The CEM provides a method which can stimulate cost-effective improvements by organisations involved in restoration work.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution and support of all colleagues in the Conservation Excellence Assessment Network who, as qualified independent assessors, reviewed cases related to this study, namely: Wilna Accouche, Elysia Barker-Davies, Christell Chesney, Jamieson Copsey, Anita Diederichsen, Hugh Doulton, Shannon Farrington, Charlotte Gardener, Samuel Leslie, Naing Lin, Thirza Loffeld, Jocy Yu-Wen Li, Erik Meijaard, Helen Meredith, Augusta Moore, Nieves Navarro-Fuentes, Laura Nery-Silva, Kerstin Opfer, Harilala Rahantalisoa, Yasmireilda Richard, Danita Strickland, Laura Talbert, Ros Warwick-Haller, Regine Weckauf and Koral Wysocki. Appreciation also to Jim Groombridge for comments on an early version of this research paper.

None.

©2022 Amavassee, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.