International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

1Laboratory of Ecology and Ecotoxicology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lomé, Togo

2Laboratory of Botany and Plant Ecology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lomé, Togo

Correspondence: Aboudoumisamilou Issifou, Laboratory of Ecology and Ecotoxicology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lomé, Lomé 01, Togo, Tel +22890183284

Received: September 13, 2022 | Published: September 26, 2022

Citation: Issifou A, Atakpama W, Segniagbeto GH, et al. Use and vulnerability of fauna in the northern part of the Mono Basin in Togo, West Africa. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2022;6(1):32-39. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2022.06.00181

The wildlife habitats of the Mono plain in Togo are increasingly fragmented under the effect of anthropogenic threats, making wildlife even more vulnerable. This study aims at determining the endogenous knowledge of the vulnerability of the fauna of the Mono River plain in Togo. Data were collected based on semi-structured ethnozoological surveys by individual and focus group interviews of 185 respondents, mostly hunters neighbouring the protected areas of the Mono River plain. The fauna reported was 65 species divided into 58 genera and 40 families from which 15 ungulates and sixs (6) primates. At the local scale, 16.43% and 20.16% of the fauna was reported respectively less available and rare. There are two (2) reported rare species highlighted based on the consensus value (CV): the waterbuck, Kobus ellipsiprymnus (CV=0.72) and the antelope, Hippotragus equinus (CV= 0.7) and two (2) less available species: the boa, Python sabae (CV=0,75); the red buffalo, Syncerus caffer nanus (CV=0.80). Among the species listed, 14 are vulnerable according to the IUCN classification criteria. They are: six (6) critically endangered (Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster, Colobus vellerosus, Cyclanorbis elegans, Erythrocoebus patas spp. patas, Kynixys homeana, and Loxodonta africana), three (3) endangered (Centrochelys sulcata, Lycaon pictus, and Phataginus tricuspis) and five (5) vulnerable (Aquila rapax, Crocodylus suchus, Kinixys belliana, Kinixya homeana, and Panthera leo). The completeness studies will give better appreciation of the so-called vulnerable/threatened species, namely their spatial distributions, the size of their population and the level of fragmentation of their habitat.

Keywords: ethnozoology, primates, ungulates, mono river, Togo

Most of Africa's natural ecosystems are an ecologically, economically and socially vital for local populations. Among natural resources found within these ecosystems, wildlife occupies a prominent place.1,2 Today, following anthropogenic pressures induced by population growth and the increase in demand for wild meats, protected areas, biodiversity sanctuaries are proving to be the preferred refuge area for wildlife.3 These protected areas, far from being inviolable areas and a haven of peace for wildlife, are also affected by anthropogenic threats, including poaching.2 Added to poaching mainly affecting primates and mammals, deforestation, agricultural expansion, mining and wildfires contribute to the fragmentation and the reduction in the quality of wildlife habitat.4–6 All these threats affect the survival and the reproduction of wildlife.

The study of the interrelation between wildlife and humans is ethnozoology.7 This science dealing with knowledge of uses, perceptions and representation of wildlife by communities occupies a prominent place in the process of sustainable wildlife management.1,2 It helps at understanding quickly the state of wildlife populations, namely the state of conservation, exploitation, dynamics and viability of wildlife habitats based on endogenous knowledge.8

Having at heart the protection of biodiversity in general and that of the fauna, Togo, one of the countries of West Africa has set up 83 protected areas (PA). Unfortunately in the face of the socio-political unrest of the 90s, these PAs are invaded.9 Some of these PAs have completely degraded and only exist in name only.10 The occupation of PAs and the conversion of their ecosystems into agrarian and residential areas have been the subject of several studies.11–14 Because of population density and socio-economic importance, the ecosystems of southern Togo and wetlands are the most impacted by spatial changes.13,15–17 Wildlife remains the most impacted by these activities. Among the various wildlife studies,18–22 there is little consideration of endogenous knowledge [2]: the perception, uses and dynamics of wildlife populations. This study is a contribution to the sustainable management of natural resources including wildlife in Togo. More specifically, it aims at evaluating the of use and the vulnerability of the fauna of the northern part of the Mono River Basin in Togo.

Description of the study area

The study is conducted throughout the basin of Mono River in the southeast of Togo straddling ecological zones III and V of Togo.23 The hydrographic network includes the Mono River and its tributaries Ogou and Anié. This Mono plain is more and more coveted by breeders because of its dense hydrographic network, favourable to the development of a diversity of fodder plants.24 There are several natural formations: savannahs, open forests, riparian forests along rivers and dense dry forests most often located in protected areas and community forests.25–28 It also hosts a peneplain developed on the gneissic granito crystalline base and dominated to the southeast by inselbergs, sanctuaries of floristic diversity29 and natural and artificial wetlands.30 The main types of soils described by Lamouroux M 31 are mainly vertisols and ferralitic soils.

The relatively diverse fauna is found in all types of plant formations. Small mammals, mostly rodents, are often found in fallow land, fields, savannahs, etc. Mammals such as antelopes, buffaloes, etc., are more localized in protected areas and in some forest relics (MERF, 2014). The study environment is home to primate species highly threatened by human actions, including Erythrocebus patas, Cercopithecus erythrogastererythrogaster, Cercopithecus mona, Chlorocebus tantalus, Colobus vellerosus, and Papio anubis.22,32 The boa is also found in some protected areas of the area and represents a sacred species among many others. The avian fauna is very diverse with raptor birds, ground-dwelling birds, passerines and non-passerine birds, etc..33 Agriculture and livestock are the main socio-economic activities for the local populations.34 Agricultural activities are very climate-dependent covering the two rainy seasons. In addition to agriculture, breeding is the second activity developed by the populations. The populations also engage in trade and fishing Figure 1.

Data collect

Ethnozoological surveys were carried out among the 185 hunter/manager respondents surrounding the protected areas and community forests of the Mono River plain in Togo from June 28 to July 10, 2022. Only two (2) inclusion criteria were taken into account: being hunters or managers of a protected area/community forest and living in the area for at least fifteen years. The hunters were identified beforehand thanks to the managers of the protected areas and community forests then by the step-by-step technique which consists in identifying the next respondent thanks to the previous one. Mainly involved in the search wild meat, hunters remain the people who can give a more accurate idea of wildlife availability. The choice of respondents was made randomly without distinction of gender or age.35 There are 22% of women and 71% of men distributed among 46 localities. The average age is 49 years old.

The methodology was based on semi-structured individual and group interviews.35 The questionnaires were designed and deployed using the Kobocollect mobile application. The discussions were conducted mainly in the local language with the help of local interpreters. The information sought was: the vulnerable fauna found in the area, in particular the species of ungulates and primates, local names, the level of vulnerability of each of the faunal species reported, its dynamics, the responsible threats, the last reported wildlife sighting and capture. The assessment of endogenous knowledge of the vulnerability of the fauna was based on the pebble technique: on a set of 10 pebbles representing the entire population, the respondent chooses the number of pebbles corresponding to the rate at current population rate. Thus four (4) vulnerability classes have been defined: very available (reduction of less than 25%), available (reduction of between 25 and 50%), less available (reduction of between 50 and 75%) and rare (reduction of more than 75%). In addition to these four (4) classes, there are also species that have disappeared.

In addition to this primary information, other additional information: confirmation of animals reported and observation of hunting trophies were obtained from managers of protected areas and community forests, as well as local authorities and traditional healers often using the parts of animal organs in various health, religious and dietary practices. This additional information also made it possible to highlight the socio-cultural importance of the fauna.

Data analysis

The data collected was extracted from the kobocollect tool in Excel spreadsheet, then formatted for statistical processing. The citation frequency (Fr, %) of each reported wildlife species is determined by the relationship: with n = number of respondents reporting the species and N = total number of respondents. In addition to citation frequency, endogenous knowledge of wildlife vulnerability was assessed from the consensus value (CV).36 The VC is the ratio between the number of respondents who reported one of the four defined vulnerability classes (very available, available, less available or rare) for a species “i” (NCi) over the total number of respondents (NCmax). It expresses the consensus of the respondents for a class of vulnerability and its value varies from 0 to 1. The CV approaches 1 when the respondents are almost unanimous on a level of vulnerability. All listed species have been classified into families and genera. Their conservation status according to the vulnerability scale of the International Union for Conservation of Nature37 were also sought. The list of scientific names of fauna is established and confirmed on the basis of the literature on animal species of Togo.18,21,22,38

Fauna diversities reported

The number of trophies listed is 272 for 36 animal species out of 65 reported species (Figure 2). Observations of live specimens were also made (Figure 3). Added to hunting trophies and live specimens, other photos of killed animals were also taken. Overall, the faunal diversity reported and identified is 65 species divided into 58 genera and 40 families. The most reported species are: Buffon's kob (Kobus cob, 88.46%), bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus, 82.69%), the black buffalo (Syncerus cafer cafer, 78.85%) and Walter's duiker (Philamtomba walteri, 78.85%) (Figure 4). These species are reported to be rare to less abundant by the respondents. The consensus value is respectively 0.83 (very available), 0.51 (available), 0.53% (rare) and 0.56 (rare). Ungulates (Bovidae, Suidae and Hippopotamidae) remain the largest group with a total of 15 species. Bovidae are the most reported (12 species), against two Suidae and one Hippopotamidae (Table 1). They are assisted by primates, including 5 Cercopithecidae and 01 Galagonidae and birds of the Musophagidae family (3 species). The primate species reported are: Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster, Colobus vellerosus, Chlorocebus tantalus, Erythrocebus patas, Galago senegalensis, and Papio anubis. Accipitricidae, Testudinidae, Felidae, Cisticolidae and Suidae are each represented by two (2) species. The remaining 30 families each include one species (Figure 5).

Figure 2 A few hunting trophies encountered.

a= Papio anibus, b= Crocodilus suchus, c= Kobus kob, d= Syncerus cafer cafer, e= Hypotragus equinus, f= Cephalophus rufulatus, g= Cephalophus rufulaphus, h= Syncerus cafer cafer

Figure 3 A few live specimens encountered among the populations.

a = Cyclanorbis elegens, b = Centrochelys sulcate, c= Kinisys belliana nogueyi, d= Eurithrocebus patas, e= Chlorocebus tantalus.

Order |

Families |

Scientific names |

Common names |

Vernacular names |

UICN status |

Accipitriformes |

Accipitridae |

Aquila rapax |

Tawny Eagle |

Djelo |

VU |

Accipitridae |

Accipiter gentilis |

Vulture |

Tolowi |

LC |

|

Artiodactyls |

Bovidae |

Alcelaphus buselaphus |

Hartebeest |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Syncerus cafer cafer |

black buffalo |

Eto |

NT |

|

Bovidae |

Syncerus caffer nanus |

red buffalo |

Efankoukpan |

NT |

|

Bovidae |

Cephalophius rufilatus |

Rufous-flanked duiker |

LC |

||

Bovidae |

Sylvicapra grimmia |

grimm's duiker |

Kpèrè |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Philantomba walteri |

walter's duiker |

Okounou |

DD |

|

Bovidae |

Kobus kob kob |

Buffon's cob |

Abissa |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Kobus ellipsiprymnus |

waterbuck |

Kodjokpéé |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Tragelaphus scriptus |

Bushbuck |

Abissa |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Hippotragus equinus |

Antelope |

Lelou |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Ourebia ourebi |

Ourebi |

Mouan |

LC |

|

Suidae |

Phacochoerus africanus |

warthog |

Kpéré |

LC |

|

Suidae |

Potamocherus porcus |

bushpig |

Katchi |

LC |

|

Bovidae |

Kobus ellipsiprymnus |

Waterbuck |

Otolo |

LC |

|

Carnivores |

Felidae |

Felis sulvestris |

black bush cat |

LC |

|

Kanidae |

Lycaon pictus |

Wild dog |

Kpambare |

EN |

|

Viverridae |

Civettictis civetta |

Civet |

Ebè(Adja) |

LC |

|

Hippopotamidae |

Hippopotamus amphibius |

Hippopotamus |

Gbogbo |

VU |

|

Herpestidae |

Ichneumia albicauda |

Hyena |

Lanwaya(Adja) |

LC |

|

Felidae |

Panthera leo |

Lion |

Djanta |

VU |

|

Mustelidae |

Aonyx capensis |

Otter |

Awawa |

NT |

|

Herpestidae |

Ichneumia albicauda |

white-tailed mongoose |

LC |

||

Felidae |

Leptailurus serval |

Serval |

Soglo |

LC |

|

Columbiformes |

Columbidae |

Stretopelia bitorquata |

Double Collared Dove |

Corokoto |

LC |

Alcedinidae |

Alcedo Atthis |

Kingfisher |

LC |

||

Crocodiles |

Crocodylidae |

Crocodylus suchus |

Crocodile |

Élo |

VU |

Eulipotyphles |

Erinaceidae |

Atelenix albiventris |

Hedgehog |

Kassangbèna |

LC |

Galliformes |

Phasianidae |

Francolinus bicalcaratus |

Francolin |

Takpè |

LC |

Numididae |

Numida meleagris |

numindi guineafowl |

Tabsou |

LC |

|

Lagomorphs |

Leporidae |

Lepus lepus |

Hare |

LC |

|

Musophagiformes |

Musophagidae |

Corythaeola cristata |

Giant Turaco |

Yéso |

LC |

Musophagidae |

Crinifer piscator |

gray turaco |

Kpelou kpelou |

LC |

|

Musophagidae |

Tauraco persa |

green turaco |

LC |

||

Passeriformes |

Pycnonotidae |

Pycnonotus barbatus |

common bulbul |

Kangotira |

LC |

Corvidae |

Corvus albus |

Pied Crow |

LC |

||

Cisticolidae |

Cisticola brachypterus |

Short-winged cisticola, |

Tété |

LC |

|

Cisticolidae |

Cisticola eximius |

black-backed cisticola |

LC |

||

Hirundinidae |

Cecropis domicella |

Swallow |

Fabia |

NE |

|

Pelecarniformes |

Ardeidae |

Bubulcus ibis |

Cattle Egret |

Bélé bélé |

LC |

Pholidotes |

Manidae |

Phataginus tricuspis |

Pangolin |

Kadankparé |

EN |

Primates |

Cercopithecidae |

Colobus vellerosus |

magistrate colobus |

Don'ko |

CR |

Galagonidae |

Galago senegalensis |

Galogo |

LC |

||

Cercopithecidae |

Papio anubus |

Gorilla |

Kadja |

LC |

|

Cercopithecoidea |

Erythrocoebus patas |

Patas |

Efio |

CR |

|

Galagonidae |

Galago senegalensis |

Potto juju |

Nkomila |

LC |

|

Cercopithecoidea |

Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster |

red bellied monkey |

Boungarima |

CR |

|

Cercopithecidae |

Chlorocebus tantalus |

Vervet |

Eklan |

LC |

|

Proboscideans |

Elephantidae |

Loxodonta africana |

Elephant |

Dzadjo |

CR |

Rodentians |

Anomaluridae |

Zinkerella insignis |

abnormality |

Koukouroubata |

LC |

Thryonomyidae |

Thryonomyx swinderianus |

Cane rat |

Ro |

LC |

|

Sciuridae |

Heliosciurus gambianus |

Squirrel |

LC |

||

Hystricidae |

Hystrix cristata |

porcupine |

Samirè |

LC |

|

Squamates |

Boidae |

Python sebae |

Boa |

NT |

|

Colubridae |

Chironnius exoletus |

green memba |

LC |

||

Varanidae |

Varanus exanthematicus |

monitor lizards |

Evé |

LC |

|

Viperidae |

Bitis arietans |

Viper |

Djakpata |

LC |

|

Strigiformes |

Strigidae |

Bubo africanus |

African Grand Duke |

Biou |

LC |

Testudines |

Testudinidae |

Centrochelys sulcata |

spurred tortoise |

Kassawaléa |

EN |

Testudinidae |

Kinixys belliana nogueyi |

kinixys of Bell |

VU |

||

Testudinidae |

Kinixys erosa |

freshwater turtle |

Obèlè |

DD |

|

Testudinidae |

Kinixya homeana |

CR |

|||

Trionychidae |

Cyclanorbis elegans |

freshwater turtle |

Abèbè |

CR |

|

Tubulidentates |

Orycteropodidae |

Orycteropus afer afer |

Mole |

Ogourougourou |

LC |

Table 1 List of reported species: scientific names, vernacular and common names and IUCN status

Endogenous knowledge of wildlife vulnerability

Overall, the fauna reported is qualified as available in 39% of cases against less available and rare respectively by 16.43% and 20.16% (Figure 6). According to consensus values, there is two (2) rare species: the waterbuck, Kobus ellipsiprymnus (VC = 0.72) and the hipotrag, Hippotragus equinus (VC=0.7). The boa, Python sabae (VC=0.75), the red buffalo, Syncerus caffer nanus (VC = 0.80) were reported as less available. Although the reduction in the size of the populations is observed, this reduction does not reach 50% certain species said to be still available: the viper, Bitis arietans (CV=0.69), the porcupine, Hystrix cristata (CV = 0.58), S. caffer cafer (CV=0.79), the bushpig, Potamocherus porcus (VC=0.66), Grimm's duiker, Sylvicapra grimmia (CV=0.58), T. scriptus (CV=0.69), the anomalous, Anomalurus beecrofti (CV = 0.88), and the red-flanked duiker, Cephalophius rufilatus (CV = 0.90). There are also two (2) species said to be still very available: the serval, Leptailurus serval (CV = 0.83) and the hyena, Ichneumia albicauda (CV = 0.93). For the other remaining species, the CV data does not provide a clear enough idea of their vulnerability.

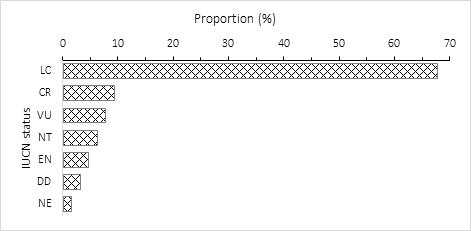

Status of species according to IUCN vulnerability criteria

According to the IUCN vulnerability criterion, the majority of species are said to be of little concern (LC, 67.69%). Threatened, Critically Endangered (CR), Vulnerable (VU) and Endangered (EN) species represent 9.23%, 7.69% and 4.61% respectively (Figure 7). These are six (6) critically endangered species: the red-bellied monkey (Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster), the magistrate colobus (Colobus vellerosus), the freshwater turtle (Cyclanorbis elegans), the pasta (Erythrocoebus patas spp. patas), the African savannah elephant (Loxodonta africana), and Kinixys homeana. The vulnerable species are five (5): the tawny eagle (Aquila rapax), West African crocodile (Crocodylus suchus), the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), Kinixys belliana nogueyi, and the lion (Panthera leo). The three (3) endangered species are: the spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) and the pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis). Four (3) near-threatened species were also reported: otter (Aonyx capensis), P. sebae, S. caffer cafer et S. caffer nanus Existing data do not allow defining the level of vulnerability of the Walter's Duiker and the freshwater turtle (Kinixys erosa). Among the 65 species reported, only one species is not on the IUCN list of assessed species: the swallow (Cecropis domicella).

Figure 7 Status of species identified according to IUCN vulnerability criteria.

NE, not evaluated; DD, data deficient; LC, least concern; NT, near threatened, VU, vulnerable; EN, endangered CR, critical endangered.

Cause of wildlife regression

Eight (8) main causes of wildlife regression have been reported. The most reported threats are deforestation (33.07%) and hunting (21.26%). The construction of housing infrastructure (13.90%) and the advance of the agricultural front (12.60%) come in second place. The socio-political troubles of the 90s and the recent and recurrent use of herbicides are weakly incriminated (Figure 8).

Local use of reported vulnerable species in Mono River Basin of Togo

Almost the majority of reported species are used by the resident population. There are three main types of use: food use, medicinal use and artisanal use. Food use is the most reported (55.46% of cases), followed by artisanal use (24.89%). Medicinal use comes last (19.65%). This trend changes when considering the number of species: 40 species reported in food, 22 in traditional medicine and 12 in handicrafts. Some species are found in food, traditional medicine and crafts. This is the case of: K. cob, T. scriptus, S. cafer cafer, P. walteri, and Phacochoerus africanus. The species, types of uses and parts of animal organs used can be found in Table 2. Seventeen (17) types of animal parts used were discriminated. The most used animal parts are the skin (30.12%) and the flesh (34.93%). Horns come in third place (11.79%). They are mainly used in magico-mystical practices and dances. As part of celebrations, they are placed on the head or used as musical instruments. The other animal parts of organs were mainly reported very weakly represented (Figure 9).

Type of uses |

Scientific names |

Animal parts |

Meat |

Accipiter gentilis |

Flesh |

Alcedo Atthis |

Flesh |

|

Atelenix albiventris |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Bubo africanus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Bubucus ibis |

Flesh |

|

Cecropis domicella |

Flesh |

|

Cephalophius rufilatus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster |

Flesh |

|

Chlorocebus tantalus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Cisticola brachypterus |

Flesh |

|

Cisticola eximius |

Flesh |

|

Civettictis civetta |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Corvus albus |

Flesh |

|

Crinifer piscator |

Flesh |

|

Erythrocoebus patas |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Felis sulvestris |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Francolinus bicalcaratus |

Flesh |

|

Galago senegalensis |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Hystrix cristata |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Ichneumia albicauda |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Kinixys erosa |

Flesh |

|

Kobus kob |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Kobus kob kob |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Leptailurus serval |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Lycaon pictus |

Flesh |

|

Numida meleagris |

Flesh |

|

Papio anubus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Phacochoerus africanus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Philantomba walteri |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Potamocherus porcus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Pycnonotus barbatus |

Flesh |

|

Python sebae |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Stretopelia bitorquata |

Flesh |

|

Sylvicapra grimmia |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Syncerus cafer cafer |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Syncerus caffer nanus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Tauraco persa |

Flesh |

|

Thryonomyx swinderianus |

Flesh |

|

TrageLaphus scriptus |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Zinkerella insignis |

Flesh, Skin |

|

Handcrafted |

Corythaeola cristata |

Feather |

Crocodylus suchus |

Skin |

|

Hippotragus equinus |

Horns, Skin |

|

Kobus ellipsiprymnus |

Horns, Skin |

|

Kobus kob |

Horns, Skin |

|

Loxodonta africana |

Ivory, Skin, Bone |

|

Lycaon pictus |

Skin |

|

Phacochoerus africanus |

Horns, Teeth |

|

Philantomba walteri |

Horns, Skin |

|

Sylvicapra grimmia |

Horns, Skin |

|

Syncerus cafer cafer |

Horns, Bones, Skin, Tail |

|

TrageLaphus scriptus |

Horns, Skin |

|

medicinal |

Alcelaphus buselaphus |

Dejection |

Type of uses |

Aquila rapax |

Legs, Head |

Meat |

Bitis arietans |

Head |

Centrochelys sulcata |

Shell |

|

Cephalophius rufilatus |

Clogs |

|

Corythaeola cristata |

Feathers, Head |

|

Cyclanorbis elegans |

Fat |

|

Erythrocoebus patas |

Skull, Hand, Tail, Head |

|

Hippopotamus amphibius |

Skin |

|

Hippotragus equinus |

Horns, Hooves |

|

Hystrix cristata |

Scales, Skin |

|

Kobus kob |

horns |

|

Orycteropus afer afer |

Horns, Bones, Tail, Hooves |

|

Ourebia ourebi |

Horns, Hooves |

|

Papio anubus |

Skull, Hand, Skin |

|

Phacochoerus africanus |

Teeth, Fat |

|

Phataginus tricuspis |

Scales |

|

Philantomba walteri |

Skin |

|

Potamocherus porcus |

Bone |

|

Python sebae |

Fat, Skin, Tail, Head |

|

Syncerus cafer cafer |

horns |

|

TrageLaphus scriptus |

Skin, Hooves |

Table 2 Local use of vulnerable animals in the Mono River Basin in Togo

The present study reports a faunal richness of 65 distributed species, including 15 ungulates and 06 primates. The faunal diversity reported in this study is almost double that recorded by2 in the surrounding area of the Fazao-Malfakassa Faunal Reserve (FMFR) in the Central Region of Togo. There is also a slightly greater diversity of ungulates and primates in the present study compared to the inventories and wildlife surveys of the RFFM.2,19 The diversity of primates is identical to that of the Togodo Protected Areas Complex (TPAC)39,40 and slightly less than the Mono River Transboundary Reserve in Togo.20 In contrast, the diversity of ungulates is a little higher than that reported at the level of the Togodo protected area complex and the Mono River transboundary reserve in Togo respectively 10 and 1221,40 and smaller than that of.18 These differences would be linked to the disparity in the sizes of the study areas and the methodologies adopted. However, some species of primates and ungulates reported in previous studies are not found in the list. This absence may be due to the non-existence or non-discovery of specimens or the confusion being at the origin of the non-determination of certain species reported during the study.

The higher number of primates and ungulates reported by respondents testifies to the good knowledge of these species and the daily use of products derived from these animals. The common use of ungulates and primates by humans was reported by previous studies on hunting game.2,41 Wild meat is used in food, medicine, magico-mystical rituals, cosmetics, and crafts and is traded.1,2,41 Uncontrolled pressure leads to a reduction in the resource and constitutes a threat to the survival and multiplication of wildlife. The reduction of speculation and the development of wild meat substitutes are seen as a method of reducing hunting pressure.42 The marketing of wild meat being a source of income for hunters, only the retraining of actors towards other income-generating activities remains the best solution.

Deforestation is causing the fragmentation and reduction of habitat and the quality of wildlife habitat as well as the size of animal populations.43 This degradation is linked to the growth of the human population which consequently induces an increase in the livings and agricultural areas as well as the need for meat products. In the plain of the Mono River in Togo, in recent years there has been a very strong degradation of the natural vegetation to the benefit of anthropogenic formations, mining operations and dwellings.5,13,44 Apart from the Abdoulaye wildlife reserve (AWR), whose forest ecosystems seems to be recovering more,27 much of the protected areas meant to be wildlife refuges are increasingly degraded14 throughout the Mono River Basin. Studies on the degradation of plant formations in the area remain fragmented and do not allow us to give a more precise idea of the fragmentation of the wildlife habitat.5,13,14 The fragmentation of wildlife habitat does not contribute to the protection of several wildlife species including primates and mammals including ungulates even inside protected areas.45 This degradation of wildlife habitat is also observed in other countries of the sub-region and calls for specific and common actions, in particular the strengthening of the protection of protected areas.

Although cited in second position after the loss of habitat, hunting remains the anthropogenic pressure most directly responsible for the reduction of animal populations and the degradation of vegetation.45,46 In order to meet the ever-increasing demand for meat products, there has been an increase in the herd of herbivores in recent years.47 This type of livestock farming being highly dependent on natural ecosystems, in particular large livestock whose feed is at the origin of transhumance also contributes to the degradation of natural ecosystems48 especially within protected areas. Due to the preference of several persons of the wild meat; diversifying meat and awareness on the importance of the fauna are needed.

A number of 14 threatened wildlife species according to the IUCN vulnerability criteria [36] have been reported in the Mono River plain. This number of vulnerable species is more represented than those reported at the level of the AWR.33 Beyond vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List, attention should be paid to data-deficient species and species locally highlighted to be vulnerable in the area. Better management of protected areas, in particular better protection of the ecosystems of PA, would ensure the protection of this fauna and reduce the impact of anthropogenic pressure.

This study made it possible to make an inventory of endogenous knowledge of the vulnerability of the fauna and habitats in the northern part of the MRB. The faunal diversity reported is 65 species divided into 58 genera and 40 families. The fauna reported mainly includes ungulates (15) and primates. This fauna includes 14 vulnerable species according to the IUCN species vulnerability scale: six (6) critically endangered (Cercopithecus erythrogaster ssp. erythrogaster, Colobus vellerosus, Cyclanorbis elegans, Erythrocoebus patas spp. patas, Kynixys homeana, and Loxodonta africana), three (3) endangered (Centrochelys sulcata, Lycaon pictus, and Phataginus tricuspis) and five (5) vulnerable (Aquila rapax, Crocodylus suchus, Kinixys belliana, Kinixya homeana, and Panthera leo). This study highlighted two (2) less available species (Kobus ellipsiprymnus and Hippotragus equinus) and two (2) rare species (Python sabae and Syncerus caffer nanus). The threats responsible for the vulnerability of wildlife are in particular deforestation and hunting. Particular attention should be paid to these species in future studies: their spatial distributions, the size of their populations and the level of fragmentation of their habitats. Sensitization of hunters on wildlife conservation measures and their conversion to other income-generating activities is necessary.

The authors would like to thank hunters and managers of protected areas and community forests in the Mono River Basin of Togo who agreed to provide the information needed to write this manuscript. All our gratitude to the authorities of the Ministry in charge of the Environment, in particular the regional and prefectural directors who guided and facilitated the progress of the data collection while remaining discreet in order to allow better contact with hunters.

None.

©2022 Issifou, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.