International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Case Report Volume 2 Issue 2

Carnivorous Project, Cananéia Research Institute, Brazil

Correspondence: Giovanne Ambrosio Ferreira, Instituto de Pesquisas Cananéia - IPeC. Rua Tristão Lobo 199 Centro, Cananéia, SP. 11990–000, Brazil

Received: May 24, 2017 | Published: July 21, 2017

Citation: Ferreira GA, Genaro G. Predation of birds by domestic cats on a neotropical island. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2017;2(2):60-63. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2017.02.00017

The domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus) is indicated as a threat to several native species in different regions where they occur, especially seabirds in insular environments. In this study, we present the results obtained through fecal analysis and identification of the remains of prey killed by domestic cats in a fishing village in an insular area of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Although several species of seabirds use the island either as a migratory route, residence, or for nesting, we did not detect their presence among the identified items. However, other species of birds, mainly Passeriformes, were found. This corresponded to less than 10% of the total of items identified as predated by domestic cats during the sampling period. We emphasize the importance of carrying out new studies, as well as evaluating measures to identify more sensitive species and preventing potential impacts caused by felines in forest remnants in Neotropical regions.

Keywords: felis silvestris catus, impact of predation, atlantic forest, birds, exotic species, island

Although regarded as a pet, the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus) (Linnaeus, 1758) is indicated as a threat to several native species in the different regions where they occur. This is true even under domiciliary conditions –living in close association with humans in anthropic areas, where all their biological requirements are intentionally met1 – or in semi-domiciliary conditions –a lesser association, where they have free access to the external areas of the residence and the possibility of exploiting available resources. Regardless of their feeding and behavioral relationship with man, cats may still display opportunistic predation behavior.2-5 For this reason, cats have been indicated as one of the main causes of the decline of other species in different areas of the world.3-12 Research has also highlighted the significant impact of predation by cats on native fauna, especially regarding birds in insular environments.8-11

This study aims to identify the main species of birds captured and predated by domestic cats in semi-domiciliary conditions. Research was conducted in a fishing village known as “Boqueirão Sul” in a remnant island environment of the Atlantic Forest, located on the south coast of the state of São Paulo, Southeastern Brazil (25°01′–25°03′S and 47°54′–47°53′W) (Figure 1-3). We collected and identified the remains of dead animals brought to selected residences by domestic cats, and analyzed the fecal samples collected in these properties. We identified the species via comparisons with animals deposited in collections or with the collaboration of specialists, following procedures described in the literature .13,14 Samples were collected during the monthly visits (each sampling period lasted an average of 15 days per month) between September 2009 and August 2010, and again between January 2013 and January 2015. Feces from the cats were collected from around the properties. Dead animals or their remains found in the properties or their backyards were collected, after which we checked that the cat was responsible for the death (parts consumed, teeth marks, visual confirmation of the animal playing or feeding, etc.). Some specimens of animals killed by cats were also collected and stored by the owners and delivered to the researchers after the sample period.

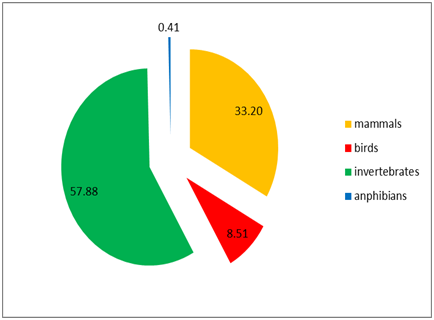

We collected 631 fecal samples (222 between 2009-2010 and 409 between 2013-2015). However, the frequency of occurrence of birds in these samples was only 6.5. We also recorded 11 instances of animal predation by domestic cats, of which nine were birds (Figure 4-7). A single remnant corresponded to a mammal, and another to an amphibian. Evidence of predation was observed in a total of 482 animals (both fecal samples and remains), with bird predation accounting for approximately 10% of these. The cats preyed mainly on invertebrates (about 58%), followed by mammals (over 33%) (Figure 8).

Of the 41 birds predated by cats, we were able to identify 12 species. Of these, 11 were of the order Passeriformes. We also identified a bird at the subfamily classification level. However, it was not possible to clearly identify the respective orders for the three records obtained in the fecal samples, as we found only a few down feathers of the birds in question (Table 1).

Figure 4 Predation records of birds by cats in semi-domiciliary conditions in a fishing village on Ilha Comprida, off the south coast of the State of São Paulo, Brazil. a. The cat returned with a southern house wren (Troglodytes musculus) in its mouth after hunting.

Figure 6 Feathers of a rufous-collared sparrow (Zonotrichia capensis) found in the backyard of a residence with semi-domiciled cats.

Figure 7 Wings of a palm tanager (Thraupis palmarum) predated by a cat and collected by a tutor at their residence.

Figure 8 Percentage of animals predated by domestic cats in the insular environment of the Atlantic Forest in Ilha Comprida, state of São Paulo, Brazil.

Order Family |

Species |

N |

popular name |

|

Birds not identified |

3 |

|||

Apodiform Trochilidae |

Trochilinae not identified |

1 |

Hummingbird |

|

Columbiform Columbidae |

Columbina talpacoti (Temminck, 1810) |

3 |

Ruddy Ground-Dove |

LC |

Passeriform Icteridae |

Molothrus bonariensis (Gmelin, 1789) |

4 |

Shiny Cowbird |

LC |

Passeriform Passaridae |

Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

2 |

House Sparrow |

LC* |

Passeriform Passerellidae |

Zonotrichia capensis (Statius Muller, 1776) |

5 |

Rufous-collared Sparrow |

LC |

Passeriform Thraupidae |

Coereba flaveola (Linnaeus, 1758) |

1 |

Bananaquit |

LC |

Passeriform Thraupidae |

Ramphocelus bresilius (Linnaeus, 1766) |

1 |

Brazilian Tanager |

LC |

Passeriform Thraupidae |

Sicalis flaveola (Linnaeus, 1766) |

3 |

Saffron Finch |

LC |

Passeriform Thraupidae |

Tangara palmarum (Wied, 1821) |

1 |

Palm Tanager |

LC |

Passeriform Thraupidae |

Tangara seledon (Statius Muller, 1776) |

1 |

Green-headed Tanager |

LC |

Passeriform Troglodytidae |

Troglodytes musculus (Neumann, 1823) |

3 |

Southern House Wren |

LC |

Passeriform Tyrannidae |

Fluvicola nengeta (Linnaeus, 1766) |

1 |

Masked Water-Tyrant |

LC |

Passeriform Tyrannidae |

Tyrannus melancholicus (Vieillot, 1819) |

1 |

Tropical Kingbird |

LC |

Passeriform not identified |

11 |

|||

Total |

41 |

|||

Table 1 Number of types of birds predated by the domestic cat, based on feces and traces of consumed prey, in the insular environment of the Atlantic Forest in Ilha Comprida, state of São Paulo, Brazil.

CS: Conservation Status; *: Exotic Specie

Some authors consider that, in general, the predatory behavior displayed by domestic cats does not affect the local fauna, which may decrease due to the availability of human resources. Thus, domestic cats use wild animals as an alternative food source, as they receive sufficient food from their owners to meet their daily needs.15 However, our research confirms that domestic cats may exhibit opportunistic predatory behavior, which occurs independently of their alimentary and behavioral relationship with humans.4,5 Apparently, this predation occurs due to the availability of prey in the environment.6,16 It is important to emphasize, however, that the problem can be aggravated, even in the case of stray cats that enter freely or have been abandoned in different natural areas. Feral cats such as the latter depend primarily on predation for their survival.17 On Reunion Island in the Western Indian Ocean, for example, the endangered species of Barau’s petrel (Pterodroma baraui) is the main victim of predation by feral cats, which has caused its population to decline.18 On Le Levant Island, to the northwest of the Mediterranean Sea, the high rate of feline predation of the Yelkouan Shearwater (Puffinus yelkouan) suggests that the local population may become extinct in coming decades, or even within a few years.19 However, and in line with the exiting literature, our results show that predatory behavior by domestic cats on vertebrates relates mainly to mammals.4,5 This is mainly due the morphology and biology of the felines.6 Ferreira et al. monitored a group of semi-domiciled cats by radio-telemetry in the same region as the present study. Their results showed a pattern of activity occurring mainly in the twilight and nocturnal periods,14 thus favoring a predation of mammals. However, even given a higher activity pattern at night, our results showed that cats predated certain species of birds in the region, especially those of the Passeriformes order. While Ilha Comprida is both a migratory route and an area where seabirds live or even nest,20–25 we did not detect the predation of any species of seabirds. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out this possibility, as we have not been able to identify some species of the predated birds. This fact, coupled with the growth of the disorderly occupation and exploitation of beaches for the purposes of tourism, may jeopardize seabird populations in the region.20 On the other hand, as in Ilha Comprida, studies show that felines can be beneficial to environments with a strong anthropogenic influence by consuming rats (Rattus sp.) and mice9 (Mus sp.) That may also predate birds’ nests.26

The present study aims to contribute to existing knowledge of the species of birds preyed on by domestic cats and to encourage future research into the preservation of avian species vulnerable to a feline presence in Neotropical environments, as well as to the adoption of strategic measures for reducing the potential impact of domestic cats in natural areas.

The authors thank the Institute de Pesquisas Cananéia – IPeC and Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora for logistic and scientific support. They also thank Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora for financial support, and Idea Wild and Formula Foods Alimentos LTDA for materials and equipment used in this project.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Ferreira, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.