International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Clinical Paper Volume 3 Issue 6

Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, UK

Correspondence: David L Williams, Cambridge Veterinary School, University of Cambridge, Madinegley Road, Cambridge, UK

Received: October 12, 2018 | Published: December 12, 2018

Citation: Inzani H, Williams DL. Comparison of rehabilitation rates of birds of prey from a raptor rehabilitation centre ten years apart. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2018;3(6):447-451. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2018.03.00139

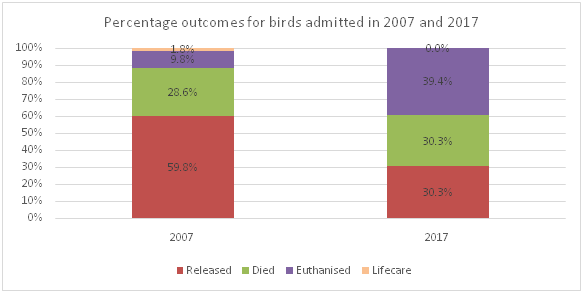

Enforcement and definitions of aspects of legislation for the rescue and rehabilitation of wildlife has been rapidly changing in recent years. The Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs has become stricter on keeping wildlife in temporary captivity for long periods of time. This has lead to anecdotal reports of reduced numbers of birds being released successfully or kept captive, and more euthanized on welfare grounds. Here we aimed to elucidate whether there is a significant difference in the outcomes of raptors admitted in to the Raptor Foundation at Pidley, UK in 2007 and 2017. Our results showed higher numbers of birds being euthanized and fewer being released successfully in 2017 (39.4 and 30.3% respectively) compared with 2007 (59.8 and 9.8% respectively). Statistically significant differences were found in the number of birds being euthanized and released in the two years selected. More work needs to be done to prove the causal reasons for these results, as many variables are involved.

The Raptor Foundation Charity, Pidley UK rescues over 100 birds a year, since its founding in 1989. The majority of these are birds of prey brought in by members of the public after road traffic collisions or young fallen from nests. The main aim of this charity is to release these birds back to their wild state, with minimal impact on their welfare.

In the early 2000s the Raptor Foundation was able to keep some of these birds in permanent captivity, providing they could be given an appropriate quality of life and were signed off by a veterinary surgeon declaring they were unsuitable candidates for release. These birds would then be used for public displays, education and in caring for owlets being rehabilitated for release. However, in recent years the Government’s Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has been stricter in the enforcement of legislation under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) regarding keeping wild birds in captive environments for greater than 15 days without a license.1 Consequently, rescue centres are discouraged from keeping wildlife for protracted periods of time in captivity. Few if any studies have investigated whether this has influenced the outcomes of birds entering the care of rescue centres. Legislation is not the only factor than could influence the success of a release, as detailed in papers such as that of Csermely2 and Fajardo et al.,3 many other factors can play a part. Therefore, the aim of this study is to elucidate if there has been any significant change in the numbers of birds released, died or euthanized over the last decade, and whether or not the cause of any differences found can be solely due to the increased legislative pressure.

The Raptor Foundation keeps hand-written records for each bird brought to the centre from each year, since the early 2000’s. Each bird has an identifying code given to it at time of admittance. Condition at arrival, location at which the bird was found, date and outcome of rehabilitation and release or euthanasia are recorded where possible. All the available data collected from 2007 and 2017 was used in this study. Species, identification code, location, incoming condition, date found/released, duration of stay, outcome, weights, sex and age for each bird was compiled.

The data was then mined using Microsoft Excel to separate outcomes (released, dead, and euthanized) for 2007 and 2017 separately.

Chi-square tests were performed on groups of the data mined from the records. This included year and outcome, sex, age, incoming complaint and species. All tests were performed to 1 degree of freedom and with a p value cut-off of 0.05 selected to highlight any significant results.

Data for outcomes of birds admitted to the raptor foundation are shown in Figure 1–6.

Outcomes in 2007 and 2017 (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Bar chart depicting the differences in percentage outcome of birds admitted in 2007 versus 2017.

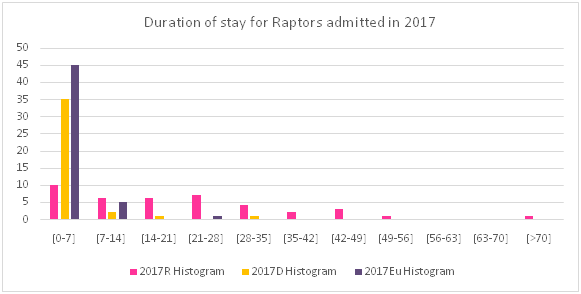

Duration of stay with the raptor foundation (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Histogram depicting the duration of stay for each bird admitted in 2007, split into ‘released’, ‘dead’ and ‘euthanised’ categories.

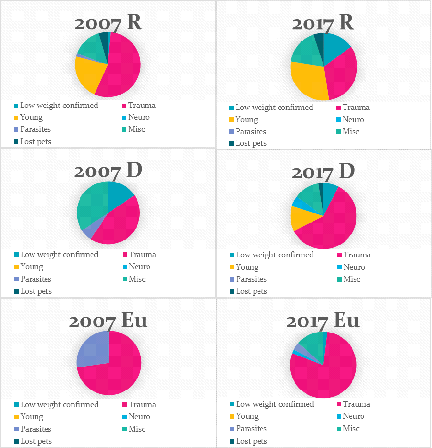

Main reason for admission versus outcome (Figure 3&4)

Figure 3 Histogram depicting the duration of stay for each bird admitted in 2017, split into ‘released’, ‘dead’ and ‘euthanised’ categories.

Figure 4 Pie charts depicted the variations in major reason for admission for each outcome in 2007 and 2017.

Gender variance in admitted birds for 2007 and 2017 (Figure 5)

Differences in species admitted for 2007 and 2017 (Figure 6)

The probability of each outcome differed between 2007 and 2017. A significant difference was found for the numbers of birds released (62 and 40, respectively) and euthanized (11 and 51 respectively) in 2007 and 2017 (Figure 1). In 2017 there was a statistically significant decrease in the numbers of birds released compared to 2007 (P value of 0.007, 1 degree of freedom and Chi-square of 7.379). Additionally, in 2017 there was a statistically significant increase in the numbers of birds euthanized, compared to 2007 (P value of 0.0001, 1 degree of freedom and Chi-square of 14.957).

The mean duration of stay in 2007 and 2017 differed for each category of bird and between the years (Figure 2&3). Mean stay in days for 2007: released birds = 26, dead birds = 6, euthanized = 8. Mean stay in days for 2017: released birds = 20, dead = 2, euthanized = 2.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of birds that died (32 and 39, respectively) in 2007 and 2017 (P value of 0.96, 1 degree of freedom and Chi-square of 0.003). And no significant difference in the incoming condition of the birds between the two years (all p values were greater than 0.05 using chi-squared tests).

The proportion of incoming cases that were attributed to trauma (RTAs, window collisions, etc) were compared for 2007 and 2017 (59 and 78 birds, respectively, Figure 4). No significant difference was found between the years for overall number of trauma cases (p value = 0.59, 1 degree of freedom, chi-square of 0.293).

Males, females and unsexed (not identified in the notes) sex birds were compared in 2007 and 2017 (Figure 5). In 2007 25 males, 23 females and 65 unsexed birds were admitted. In 2017 32 males, 43 females and 58 unsexed birds were admitted. No statistically significant difference could be found between the proportion of male or female birds admitted in each year (Males = P value of 0.78, 1 degree of freedom, chi-square of 0.08 and Females = P value of 0.11, 1 degree of freedom, chi-square of 2.601).

The numbers of kestrels and tawny owls were compared in each year, to see if there was a significant difference in the prevalence of these species (Figure 6). Both were found to be significantly difference in 2007 and 2017, with kestrels being found in greater number in 2017 and tawny owls in 2007 (kestrels = P value of 0.04, 1 degree of freedom, chi-square of 4.136 and tawny owls = P value of 0.005, 1 degree of freedom, chi-square of 7.745) Appendix 1&2.

Kestrel |

17 |

Little Owl |

14 |

Barn Owl |

20 |

Tawny Owl |

32 |

Sparrow Hawk |

11 |

Buzzard |

3 |

Falcon hybrid |

1 |

Long Eared Owl |

1 |

Ural Owl |

1 |

Crow |

1 |

European Eagle Owl |

1 |

Hobby |

3 |

House martin |

1 |

Red tailed hawk |

1 |

Great Horned Owl |

1 |

Rook |

1 |

Kookaburra |

2 |

Appendix 1 Species and numbers recorded in 2007

Kestrel |

38 |

Little Owl |

6 |

Barn Owl |

23 |

Tawny Owl |

15 |

Sparrow Hawk |

17 |

Buzzard |

25 |

Harris Hawk |

1 |

Peregrine Falcon |

2 |

American Kestrel |

1 |

Long Eared Owl |

1 |

Hobby |

1 |

Red Kite |

2 |

Marsh Harrier |

1 |

Appendix 2 Species and numbers recorded in 2017

The findings from the data kept from 2007 and 2017 highlight significance differences in the outcomes of raptors admitted to the care of the Raptor Foundation. Previous studies, such as those of Rodriguez et al.,4 Hamilton et al.,5 and Molina-Lopex et al.,6 have shown that many factors can affect how well wild birds of prey rehabilitate, including incoming causes, fitness and season. Therefore, the results discussed below are an attempt to elucidate why the Raptor Foundation in Pidley has had a change in the outcomes of their patients in recent years, and if changes in legislation are the major influencer.

This study found that over half (59.8%) of birds admitted in 2007 to the Raptor foundation were eventually released (Figure 1). This contrasts with 2017, where only 30.3% were released, with the majority being euthanized. Statistical analysis of the raw data shows that the differences between euthanasia and releases in the two years are significant (P values of 0.0001 and 0.007, respectively). It is hard to characterize the exact reason for this change in outcomes between the years using the written notes from the foundation alone. Although, there are no marked differences on the state of the birds when they were admitted to the centre and no difference between the number of birds dying during their tie in captivity which suggests that there was no difference in the health status of the birds between the two years, as discussed below. Anecdotal evidence from the Foundation’s staff suggests a legislative push for a reduction in long-term recovery periods in captivity on welfare grounds. Figure 2&3 show that there has been a difference in the duration of stay for birds in the different years, that could support this idea. In 2017 the majority of birds that were eventually released were kept under 28 days, whereas in 2007 there is a much wider distribution of duration for released birds. Birds euthanized on average have a much shorter stay in 2017 than 2007, suggesting a possible quicker decision-making process in recent years or lower threshold criteria for euthanasia. Further investigation is need to prove a link between welfare and legislative pressure and the increase in euthanasia of raptors admitted in recent years, however these results provide initial supportive evidence for the theory.

Figure 4 shows the major reasons for admission versus their outcomes in 2007 and 2017. The majority of birds overall in both years were admitted due to trauma (mostly road traffic collisions). This would comply with findings by Molina-Lopez6 and Fix and Barrows7 who showed that the majority of incoming cases are trauma-based. A higher percentage of 2007 released birds were admitted due to trauma compare to 2017 released birds (37 birds in 2007 and 13 birds in 2017). The majority of euthanized birds for both years were trauma cases. Linking the results from Figure 1&4 suggests that more of the incoming trauma cases are euthanized in 2017 compared to 2007. Additionally, no statistically significant difference could be found between the total numbers of trauma cases in both 2007 and 2017 (p = 0.59). This means that the changes in the proportions of euthanized and released birds between these years are likely to be due to more trauma birds picked as cases for euthanasia rather than rehabilitation. Reasons for this could be increased severity of trauma cases in recent years or lower injury thresholds for euthanasia candidates, as suggested above, due to their documented lower success-rates in papers such as that of Punch.8 The trauma category used in this study is too broad to elucidate the answer here, however splitting of the categories and assessing for severity of conditions in the future could answer these questions.

The proportion of raptors that died in both 2007 and 2017 was relatively similar (28.6% and 30.3%, respectively – Figure 1). No statistically significant difference was found between the two years for this outcome (p = 0.96) and the duration of stay for birds who died was less than 1 week in both years (mean stay in 2007 = 6 days and 2017 = 2 days). This suggests the most severely injured or ill birds that fail to survive rescue have not changed in the two years. Given that the severity of cases does not appear to have varied between the two years, it appears that the difference between numbers of birds released is unlikely to be associated with a difference in severity of injuries, however further categorization of future admissions by severity could help confirm this theory.

Analysis of species-based categorization of cases in Figure 6 shows the variation of species in each year. Tawny owls were the predominant species seen in 2007 (32 birds out of 113, p = 0.005), while kestrels were the most predominant species in 2017 (38 birds out of 133, p = 0.04). Further analysis of the records is needed to assess whether these species differences have affected the outcome results for these years, as papers such as Mason (2010) describe how certain species can do better in temporary captivity than others.

Additionally, sex-based categorization of cases as seen in Figure 5 shows minimal variation in the splits in 2007 compared to 2017. Statistical analysis of these cases has shown no significant difference in the numbers of males, females and unidentified individuals in these years. Better record-keeping of the sex of birds, to reduce the numbers unidentified, would be useful to better analyze the data, however the limitation is that sexing raptors is known to be difficult in non-sexually dimorphic species.

There are studies such as Csermely2 and Mason9 that, despite risks, have shown that birds of prey can be rehabilitated reasonably well despite long periods of captivity suggests that birds can be rehabilitated after long recoveries. However, limited work can be found that assesses their welfare and stress during their time in captivity. Zimmerman et al.,10 discuss the advisability of rehabilitation of monocular owls, while Kirkwood and Sainsbury11 address the ethics of interventions for wild animals. However, no studies can be found by the present authors on the welfare of raptors during temporary captivity in the UK. Therefore, a cost-benefit analysis of the welfare of birds during temporary captivity and their release success would be useful to see if the increase in euthanasia and reduction of releases in 2017 is in the birds’ best interests long term.

Captivity does have risks, such as disease,12 stress,9 loss of fitness,5,13 and many more. Therefore, even temporary captivity for rehabilitation needs to be properly assessed for risk-benefits. As Kirkwood and Sainsbury11 and Boal et al.,14 describe, the reasons for rehabilitation of a wild animal must first consider its best interests and the ethics of treating it before release, rather than more superficial feelings of responsibility alone.

The findings in this study highlight a change in the way wild raptors are handled by the Raptor Foundation in recent years. More focus appears to be on the quicker releases and reduced time in captivity. With their priority being the welfare of the birds in their care and the issues with long captivity described above, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Foundation has shown these changes. This aligns with the stricter enforcement of the WCA1 by DEFRA. Our findings show that it is highly likely that the legislative push by DEFRA is a major influencing factor behind the changes found at Pidley.

However, more work needs to be done in this area, especially considering the vast amounts of data available. Although we have found that the numbers released and euthanized in 2007 compared to 2017 has statistically significant differences, more research needs to be done to prove this difference is due to changes in legislation, welfare assessment, changing of ethical thresholds, or to elucidate other causes.

The findings in this paper align with the conclusions draw by others. An objective assessment of the incoming and outcoming variables of birds in rescue centres will help the centres assess the quality of their rehabilitation programs. Gaining a full understanding of the severity of incoming conditions and aligning them with the likely outcomes can further help raptor rescues centres improve decision making for the care of each individual bird.

Special thanks go to the Raptor Foundation in Pidley for making their data available for this project and their advice throughout the process. Additional thanks go to Andrew Witty for his assistance in creating formulae to process the data on Excel.

Author declares that there is no conflicts of interest.

©2018 Inzani, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.