International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 1

Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, India

Correspondence: Anuradha Gupta, Department of Veterinary Anatomy, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

Received: November 22, 2017 | Published: January 12, 2018

Citation: Bala M, Gupta A, Bansal N, et al. Age related histomorphochemical changes in ovaries of Punjab white quail. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2018;3(1):28-34. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2018.03.00048

The present study was undertaken to elucidate histomorphological and histochemical studies on ovaries of Punjab white quail. The birds were divided into four age groups 8weeks, 16weeks, 24weeks and 30weeks. The study revealed that entire ovary was covered by single layer of squamous to cuboidal epithelium depended on the presence or absence of follicles. The cortex was separated from medulla by a thin layer of connective tissue called tunica albuginea at 8 weeks of age. The tunica albuginea was composed of abundance of collagen fibers with few reticular and elastic fibers. This layer started regress at 16 weeks and was completely diminished at 24 weeks and 30 weeks of age. The medulla was comprised of loose connective tissue and large number of blood vessels, lymph vessels and lacunars channels. With advancing age, these lacunars channels increased in number. Smooth muscle fibers along with nerve fibers were also seen. Micrometrical data showed that the mean height of the epithelium increased with the age but was maximum at 24 weeks of age whereas thickness of the cortex and medulla was maximum at 16 and 8 weeks of age. Histochemical studies revealed that PAS reaction was strong in the surface epithelium, moderate in the cortex and medulla. Acid mucoploysaccharides were strong in the surface epithelium, moderate in cortex and theca layers, weak in medulla. Surface epithelium showed strong to intense reaction for basic proteins. Sudanophillic lipids were weak in the epithelium, cortex and medulla.

Keywords: histomorphology, cortex, medulla, ovary, Punjab white quail

In India, quail was introduced two decades ago and has partially replaced the domestic fowl both in research and open market for human consumption. The quail originally domesticated around 11th century as a pet song bird, is now highly valued.1,2 Quail reproduces throughout the year on contrary to seasonally breeding birds. It attains the maturity at 28 days and first decline of fertility has been recorded at 12 months and last egg laid or 90% fertility loss at 17-24 months of age.3 The advantages of quail farming includes minimum floor space, low investment, comparatively sturdy birds, early market age and sexuality, high rate of egg production and less feed requirement.4 Besides, Quail meat and egg are tastier than chicken and has less fat contents. It has been shown to promote body and brain development in children and nursing mothers.5 In quail farming, the reproductive and immune status of birds is of prime importance to obtain good production.6

Quail females begin to lay eggs at the age of 45 days and the peak of egg production is attained at 5 month of age.7 The short life cycle, the high fecundity and adaptability to life in cages, the low maintenance cost, and the easy ways to raise and handle it, make the quail an ideal model for research. In comparative studies between chicken and Japanese quail, the latter gives an annual egg mass production twenty times higher than the female adult body weight, while it is only ten times in hen.8 The literature is available on the histomorphology and histochemistry on ovaries of duck,9,10 Japanese quail,11 Spotted tinamou’s,12 Chicken,13 Punjab white quail14 and domestic hen15 but information on age related changes in histomorphochemical studies of ovary in different ages of Punjab White Quail is very scanty. Keeping in view the scarcity of literature the present study was planned with the following objectives:

The present study was conducted on ovaries of 24 Punjab white quails. The ovaries of different age were collected from poultry farm, GADVASU, Ludhiana. Before collections of samples, the ovaries were thoroughly examined for any pathological lesions. The female birds of various ages were selected and grouped as 8 weeks, 16 weeks, 24 weeks and 30 weeks. The tissue samples were collected after slaughter of the birds. The particulars of birds have been described in Table 1. The ovaries were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) immediately after collection. Once the fixation was achieved, the ovaries were processed for paraffin block preparation by acetone-benzene schedule.16 The blocks were prepared and sections of 5µm thickness were cut with rotary microtome and obtained on clean glass slides. The paraffin sections were stained with different stains to study the histomorphological (Table 2) and histochemical details (Table 3). Micrometrical observations were recorded on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections with help of image analysis system loaded in digital microscope micrometer. The epithelial height, thickness of cortex and medulla were recorded in ovaries of all age groups (Tables 1-3).

Sr. No. |

Group |

Bird No. |

Source |

1 |

Group I |

A1 |

GADVASU, Poultry Farm |

2 |

-do- |

A2 |

-do- |

3 |

-do- |

A3 |

-do- |

4 |

-do- |

A4 |

-do- |

5 |

-do- |

A5 |

-do- |

6 |

-do- |

A6 |

-do- |

7 |

Group II |

B1 |

-do- |

8 |

-do- |

B2 |

-do- |

9 |

-do- |

B3 |

-do- |

10 |

-do- |

B4 |

-do- |

11 |

-do- |

B5 |

-do- |

12 |

-do- |

B6 |

-do- |

13 |

Group III |

C1 |

-do- |

14 |

-do- |

C2 |

-do- |

15 |

-do- |

C3 |

-do- |

16 |

-do- |

C4 |

-do- |

17 |

-do- |

C5 |

-do- |

18 |

-do- |

C6 |

-do- |

19 |

Group IV |

D1 |

-do- |

20 |

-do- |

D2 |

-do- |

21 |

-do- |

D3 |

-do- |

22 |

-do- |

D4 |

-do- |

23 |

-do- |

D5 |

-do- |

24 |

-do- |

D6 |

-do- |

Table 1 Details of Ovaries of Punjab White Quail used in study.

Sr. No. |

Purpose |

Method |

Source |

1 |

Routine Morphology |

Hematoxylin And Eosin |

Luna16 |

2 |

Collagen Fibres |

Masson’s Trichrome |

Luna16 |

3 |

Elastic Fibres |

Verhoeff’s |

Sheehan & Hrapchak24 |

4 |

Reticular Fibres |

Gridley’s |

Sheehan & Hrapchak24 |

5 |

Neuronal Elements |

Holme’s |

Luna16 |

Table 2 Histomorphological techniques used on paraffin sections of ovaries of Punjab White Quail.

Sr. No. |

Purpose |

Method |

Source |

1 |

Neutral Mucopolysaccharides |

Periodic Acid Schiff |

Sheehan & Hrapchak24 |

2 |

Acid Mucopolysaccharides |

Alcian Blue |

Luna16 |

3 |

Basic Proteins |

Bromphenol Blue |

Chayen25 |

4 |

Lipids |

Sudan Black B |

Chayen25 |

Table 3 Histochemical techniques used on paraffin sections of ovaries of Punjab White Quail.

Statistical analysis

Arithmetic mean, Standard error and correlation for morphometric measurements were computed and statistically analyzed for their significance.17

Histomorphology

Stroma was comprised of collagen fibers, fibroblasts, blood vessels, lymph vessels and bundles of smooth muscle fibers. Lacunae were dispersed throughout the stroma both in cortical and medullary region. These lacunae were few at 8 weeks and 16 weeks of age but marked increase in lacunae was noticed at 24 weeks which further increased at 30 weeks.

Cortex and medulla

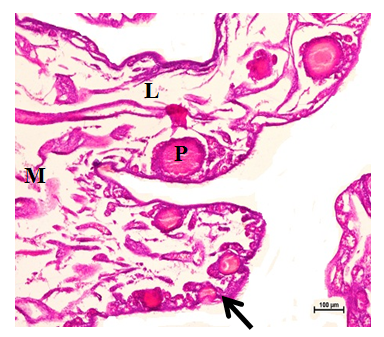

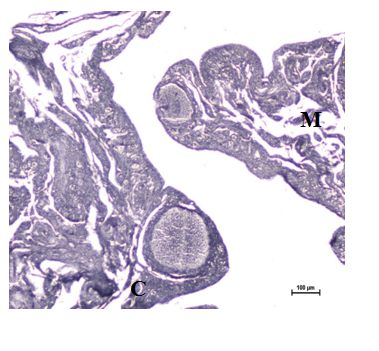

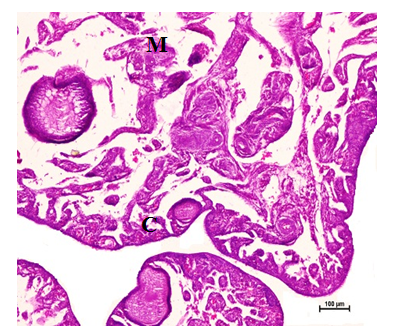

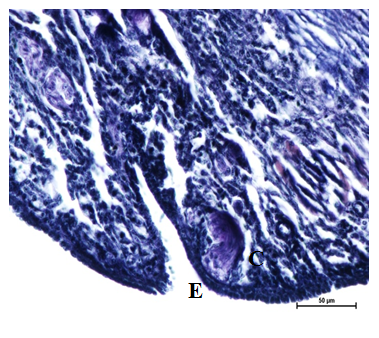

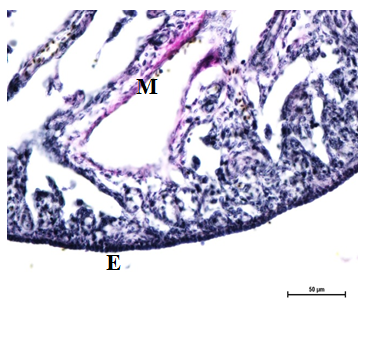

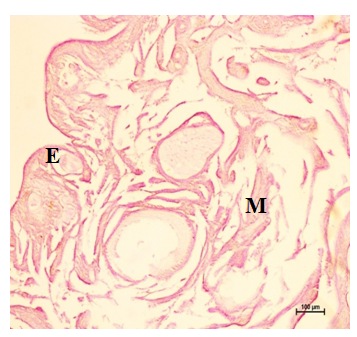

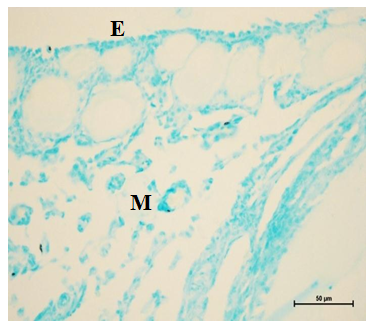

The stroma of Punjab white quail ovary consisted of outer cortex (parenchymatous zone) and inner medulla (vascular zone) in all the age groups studied. At 8 weeks of age, there was clear cut demarcation between cortex and medulla (Figure 1). Similarly, Ribeiro18 reported that before the gonadal maturation, there were two distinct regions in the ovary: the cortex, a peripheral region where the follicles were found and the medulla region, more central and made of loose connective tissue intensely vascularized and presenting nervous fibers and some smooth muscular fibers in pigeon. At 16 weeks, cortex started to interact with sub cortical medulla (Figure 2). The tunica albuginea which separated cortex and medulla regressed but the two regions could be differentiated. At 24 weeks and 30 weeks of age, the ovary did not show separation of cortex and medulla (Figures 3&4). Similarly, Rao & Vijayaragvan9 in domestic duck reported that distinction between cortex and medulla was not evident. Gonzalez-Moran19 observed that the left ovary showed well-differentiated regions, cortex and medulla at 1 day-old chicken but no distinction between cortex and medulla at 4 week old chicken. However, Deka20 in Pati and Chara-Chemballi ducks found that divisions between cortical and medullary layers became obscured. Inner medullary stroma was comprised of well vascularized and innervated connective tissue with lacunae whose covering epithelium changed with advancing age of the birds (Figures 5&6). The medulla was comprised of collagen and reticular fibers (Figure 7) with few elastic fibers (Figures 8-10).

Figure 1 Fully differentiated cortex (C) and medulla (M) at 8 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 20.

Figure 2 Ovary showing primordial and primary follicles (arrow) in cortex (C), medulla (M) seen in centre at 16 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 40.

Figure 3 Primordial (arrow) and primary follicles (P) in the cortex. Medulla (M) was composed of connective tissue, lacunar channels (L) and blood vessels at 24 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 100.

Figure 4 Primary follicles (P), medulla (M), increased lacunar channels (L) at 30weeks. H&E stain X 100.

Figure 5 Blood vessels (bv), and collagen fibers (arrow) in medulla at 24 weeks. Masson’s trichrome stain X 100.

Figure 6 Primary follicles (P) in cortex, blood vessels (bv) and few elastic fibers (arrow) in medulla at 24 weeks. Verhoeff’s stain X 100.

Figure 7 Reticular fibers in primordial follicles (Prf) in cortex and medulla (M) at 8 weeks. Gridley’s stain X 100.

Figure 8 Distribution of neutral mucoploysaccharides in the cortex (C), granulosa and theca layer of follicles at 8weeks. Periodic Acid Schiff’s stain X 100.

Figure 9 Strong to intense activity of basic proteins in the cortex (C), medulla and follicular wall of the bursting atretic follicles (BF) at 16 weeks. Bromphenol Blue stain X 100.

Figure 10 Sudanophillic lipids present in the cortex (C), medulla (M) and follicular wall at 16 weeks. Sudan Black B stain X 100.

Surface epithelium

The entire ovary was covered by single layer of squamous to cuboidal epithelium depending upon the presence of follicles (Figure 11). Similarly, Bharti 13 found in Indigenous Chicken of Assam that surface epithelium of ovary consisted of single layer of squamous epithelium with few patches of cuboidal epithelium. Bansal14 reported in Punjab white quail that surface of the entire ovary was covered by single layer of squamous to cuboidal epithelium depending upon presence of follicles. Deka20 also reported in Pati and Chara-Chemballi ducks that surface epithelium of ovary consisted of simple squamous epithelium with patches of cuboidal epithelium. Whereas Claver12 and Bhavna & Geeta21 reported in spotted tinamous and jungle babbler that ovary was covered by single columnar epithelium containing many follicles in cortical zone. The height of epithelium depended on the presence or absence of follicles. The nuclei of epithelial cells were round or oval with euchromatic basophilic and hyperchromatic material. At certain location, epithelium invaginated into cortical stroma (Figure 12&13).

Figure 11 Cuboidal epithelium (E) of ovary with irregular crypts, cortex (C), medulla (M) at 16 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 400.

Figure 12 Squamous to cuboidal epithelium, primary follicles in the cortex (C) and medulla (M) at 24 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 100.

Figure 13 Epithelium (E), connective tissue (CT) and blood vessels at 16 weeks. Hematoxylin and Eosin stain X 400.

Tunica albuginea

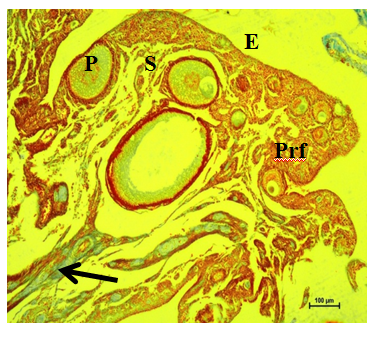

The cortex was separated from medulla by a thin layer of connective tissue called tunica albuginea at 8 weeks of age. Similarly, Gonzalez-Moran19 observed in chicken that the cortex was separated from medulla by a thin layer of connective tissue, which formed the primary tunica albuginea at 8 day old chicken. The tunica albuginea was composed of abundance of collagen fibers with few reticular and elastic fibers in all the age groups studied (Figure 14). Similar findings have been reported by Bansal [14] in Punjab white quail. The tunica albuginea was regressed at 16 weeks (Figure 15). At 24 weeks and 30 weeks, tunica albuginea was not found (Figure 16). Similarly, Ribeiro 18 reported in pigeon that the tunica albuginea got slimmer and the cortical and medulla regions were not distinguished as the gonadal maturation started.

Figure 14 Collagen fibers (arrow) underneath epithelium (E), primordial (Prf), primary (P) and secondary follicles (S) in cortex at 16 weeks. Masson’s trichrome stain X 100.

Figure 15 Elastic fibers underneath epithelium (E) of ovary, cortex and medulla, crypts in the epithelium at 16 weeks. Verhoeff’s stain X 400.

Figure 16 Elastic fibers underneath epithelium (E) of ovary, cortex and medulla (M) at 24 weeks. Verhoeff’s stain X 400.

Cortex

The cortex was occupied by numerous follicles in different stages of development viz. primordial, primary/early previtellogenic, secondary/late previtellogenic, tertiary/vitellogenic, atretic and post ovulatory follicles. In all stages of development, oocytes occupied the entire follicles leaving no antrum as reported earlier by Fitzegerald22 in Japanese quail. In the present study, no follicle was found with 2 or 3 oocytes or oocyte with 2 nuclei. Hence the chances of double yoked eggs in Punjab white quail are rare. The present findings are in accordance with Rao & Vijayaragavan9 in domestic duck (Table 4).

Sr. No. |

Epithelial Height (µm) |

Cortex Thickness (µm) |

Medulla Thickness (µm) |

|||||||||

8 wks |

16 wks |

24 wks |

30 wks |

8 wks |

16wks |

24wks |

30wks |

8wks |

16wks |

24wks |

30wks |

|

1 |

3.77 |

3.64 |

4.22 |

5.73 |

362.1 |

296.11 |

493.5 |

393.4 |

863.77 |

643.1 |

420.08 |

534.14 |

2 |

4.22 |

3.7 |

5.96 |

5.89 |

563.64 |

407.55 |

391.54 |

291.81 |

892.19 |

873.85 |

768.6 |

417.63 |

3 |

4.14 |

6.68 |

7.55 |

4.23 |

353.91 |

285.61 |

167.14 |

250.14 |

634.14 |

778.6 |

521.2 |

428.34 |

4 |

6.67 |

4.14 |

7.75 |

4.12 |

497.4 |

642.5 |

290.24 |

160.2 |

928.75 |

760.04 |

430.1 |

323.86 |

5 |

3.85 |

5.24 |

3.83 |

3.23 |

250.56 |

458.93 |

258.56 |

248.9 |

944.85 |

583.56 |

401.45 |

419.23 |

6 |

3.7 |

6.8 |

7.01 |

4.45 |

284.01 |

363.74 |

170.9 |

272.34 |

863.75 |

640.9 |

349.86 |

321.98 |

Mean |

4.391 |

5.033 |

6.053 |

4.608 |

385.27 |

409.07 |

295.31 |

269.46 |

854.57 |

713.34 |

481.88 |

407.53 |

Table 4 Micrometrical data on height of surface epithelium, thickness of cortex and medulla of ovary of Punjab white quail at different age.

Medulla

The medulla was comprised of loose connective tissue, smooth muscles and large number of blood vessels, fibers, lymph vessels and lacunar channels as reported earlier by Ribeiro18 in pigeon. With advancing age, these lacunar channels increased and became wider as reported earlier by Gonzalez Moran19 in chicken. The medullary vasculature supplied necessary supply for follicular development. All types of connective tissue fibers viz. abundant collagen fibers along with few reticular and elastic fibers were also present. Similar findings have been reported earlier by Deka 20 in Pati and Chara- Chemballi ducks. Abundant of collagen fibers with few reticular and elastic fibers were present in the tunica external layer of arteries. Elastic fibers were seen in tunica intima of arteries and veins. Smooth muscle fibers along with nerve fibers were also seen. Veins having erythrocytes in the lumen was also seen in medulla. Similarly, Bhavna & Geeta21 found in jungle babbler that stroma was composed of well vascularized and innervated connective tissue, with spaces (lacunae) whose covering epithelium changed in each period.

Micrometrical studies

The mean height of the surface epithelium of ovary was recorded as 4.391±0.422µm at 8 weeks, 5.033±0.53µm at 16 weeks, 6.053±0.63µm at 24 weeks and 4.608±0.38µm at 30 weeks of age. These findings showed that the mean height of the epithelium increased with the age but was maximum at 24 weeks of age (Table 5).The mean thickness of cortex of the ovary was as 385.27±45.4µm at 8 weeks, 409.07±49.15µm at 16 weeks, 295.31±47.66µm at 24 weeks and 269.46±28.18µm at 30 weeks whereas thickness of medulla was 854.57±42.05µm at 8weeks, 713.34±40.55µm at 16 weeks, 481.88±56.29µm at 24 weeks and 407.53±29.34µm at 30 weeks (Table 5).

Stain |

Epithelium |

TA |

Cortex |

Medulla |

|

PAS |

NMPS |

++ / +++ |

++ / +++ |

++ |

++ |

AB |

AMPS |

+++ |

++ |

++ |

+ / ++ |

Bromphenol Blue |

Protein |

++++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

Sudan Black B |

Lipids |

+ |

+ / ++ |

+ / ++ |

+ / ++ |

Table 5 Histochemical distribution of mucopolysaccharides, basic proteins and lipids in ovary of Punjab white quail.

0 : Negative; + : Weak; ++ : Moderate; +++ : Strong; ++++ : Intense.

Histochemistry

The histochemical distribution of neutral and acid mucoploysaccharides, basic proteins and sudanophilic lipids was studied in the ovarian tissues in different age groups of Punjab white quail. The study revealed that distribution of these histochemical moieties did not vary in different age groups but the reaction was variable in different structures of ovary. The histochemical distribution of neutral and acid mucoploysaccharides, basic proteins and sudanophillic lipids in ovarian tissue has been summarized in Table 5. The surface epithelium and tunica albuginea of Punjab white quail ovary showed moderate to strong reaction for neutral mucoploysaccharides (Figure 17) whereas cortical and medullary stroma was moderately positive as reported earlier by Bharti13 in indigenous chicken of Assam. They reported intense reaction in the basement membrane of granulosa cells, strong in theca interna, cytoplasm of the oocytes, membrane granulosa and moderate in the ovarian stroma, tunica albuginea and theca externa. The surface epithelium showed strong reaction for acid mucoploysaccharides (Figures 8&18) whereas tunica albuginea and cortical stroma showed moderate reactions, medullary stroma showed weak to moderate reactions. Surface epithelium showed intense reactions for basic proteins (Figures 9&19). Tunica albuginea and both cortical and medullary stroma were strongly positive for basic proteins (Figure S). Surface epithelium of ovary showed low lipid content (Figure 20). Tunica albuginea, cortical and medullary stroma showed weak to moderate reactions (Figure 20) as reported earlier by Guraya & Chalana23 in house sparrow ovary.24,25

Figure 17 Neutral mucopolysaccharides in the epithelium (E), cortex and medulla at 16 weeks. Periodic Acid Schiff’s stain X 100.

Figure 18 Acid mucopolysaccharides in the epithelium (E), cortex (C) and medulla (M) at 8 weeks. Alcian Blue stain X 400.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Bala, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.