International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Despite the tremendous contribution of eco–lodges to socioeconomic development and biodiversity conservation, there is a lack of scientific information on the issue in Ethiopia. The objective of this study was, therefore, to examine how socioeconomic and cognitive variables affect and predict the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. We hypothesized that: (i) socioeconomic variables, such as sex, age, occupation type, income, level of education, livestock and land ownership help to predict the attitudes of local people towards the ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ and (ii) cognitive variables, such as knowledge and beliefs affect the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. A structured questionnaire comprised of closed– and open–ended questions was developed and administered to examine the attitudes of the respondents. The questionnaire survey was administered to a total of 165 households. Households for the questionnaire survey were randomly selected through a lottery system based on house identification numbers. Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regressions were used to analyze the data. Generally, the results revealed that local people had positive attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’, which is consistent with our predictions. For example, a greater percentage of the respondents had positive (68%) rather than negative (32%) attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’. Moreover, the larger proportion of the respondents had positive (67%) rather than negative (33%) attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. Overall, the multiple linear regression model revealed that several socioeconomic and cognitive variables significantly affected the two groups of the dependent variables, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ (27% variance explained), and attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ (31% variance explained). Promoting the direct participation of the local people in decision–making and implementation of eco–lodge management can mitigate potential conflicts and assure long–term public support. By comparing attitudes quantified in the baseline study presented here and results from future replication of such kind of studies, researchers may provide relevant information for eco–lodge managers to deal with potential conflict of interests between eco–lodges and the needs of the local people.

Keywords: cognitive, conservation, eco–lodge, management, multiple linear regression, socioeconomic, structured questionnaire

GCCA, guassa community conservation area; GCEL, guassa community eco–lodge; GGR, guassa grassland reserve

In recent decades, several eco–lodges have been established in biodiversity rich areas of Ethiopia. For example, plenty of eco–lodges were built in Amhara, Oromia and Southern Nation, Nationalities and People’s National Regional States. Most eco–lodges are primarily established and managed to provide visiting tourists with various facilities, such as bed rooms, restaurants, transport services (e.g. boats, horses, and mules), camping sites, natural picnic areas and guiding service to trek on foot and ride on horse/mule backs.1 In return, eco–lodge owners charge the tourists and collect revenue for the facilities they have rendered. The federal and the respective regional governments also earn money by collecting taxes from the owners of the eco–lodges. In addition, eco–lodges create job opportunities to the local people because the eco–lodge owners hire both permanent and temporary workers. Local people can also earn money by providing guiding services or selling souvenirs to the arriving tourists.2

Most of the times, as eco–lodges are built from environmentally friendly, economically feasible and socially acceptable local materials, we argue that eco–lodges contribute to the conservation of the local biodiversity.3–6 As biodiversity is one of the top most attractions to tourists, eco–lodges conserve the local biodiversity from human and livestock induced disturbances. For example, when natural plants existing in the compounds of eco–lodges are reasonably protected from illegal human– and livestock–induced encroachments, they attract plenty of wild mammal and bird species from the adjacent open fields. This is because they provide the incoming wild mammal and bird species with quality food,7,8 suitable cover from environmental extremes,9 breeding sites10 and concealment from risk of predation.11 Therefore, to maintain the long term survival of our natural ecosystems, eco–lodges play a central role in local biodiversity conservation.2–6 We also illustrated how eco–lodges are linked with biodiversity conservation and socioeconomic development in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework illustrating the linkage of eco-lodges with socio-economic development and biodiversity conservation.

The successful conservation of eco–lodges is affected by the attitudes of the local people who are naturally connected with the eco–lodges and through their active involvement in eco–lodges conservation and management.12–14 Attitudes are positive or negative responses of people towards a certain phenomenon (e.g. eco–lodges).15–18 Thus, negative or positive attitudes of local people towards eco–lodges will likely affect their participation in the conservation and management of eco–lodges.13,18,19 Previous studies demonstrated that the attitudes of local people towards eco–lodges were affected by various socioeconomic variables, such as sex, age, level of education, occupation type, length of local residence, land and livestock ownership, income level, grazing land ownership and plan to stay in the area in the future. e.g14,20 Moreover, the attitudes of local people towards eco–lodges are influenced by previous benefits due to eco–lodges, knowledge of respondents about past eco–lodges management and beliefs of the respondents about eco–lodges. e.g.16,21,22

Despite the tremendous contribution of eco–lodges to socioeconomic development and local biodiversity conservation, there is a lack of scientific study that examines this issue in Ethiopia. In an attempt to bridge the gap of scientific knowledge, this study focused on investigating the attitudes of local people towards the Guassa Community Eco–Lodge (GCEL) in Menz–Gera Midir District, North Shewa Administrative Zone, Ethiopia. The objectives of the study were to: (i) determine how socioeconomic variables, such as sex, age, occupation type, income, level of education as well as livestock and land ownership predict the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’; and (ii) evaluate how cognitive variables, such as knowledge and beliefs affect the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’.

The following two hypotheses were tested: (i) socioeconomic variables, such as sex, age, occupation type, income, level of education, livestock and land ownership help predict the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ and (ii) cognitive variables, such as knowledge and beliefs affect the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. e.g.16,21,23

Study area

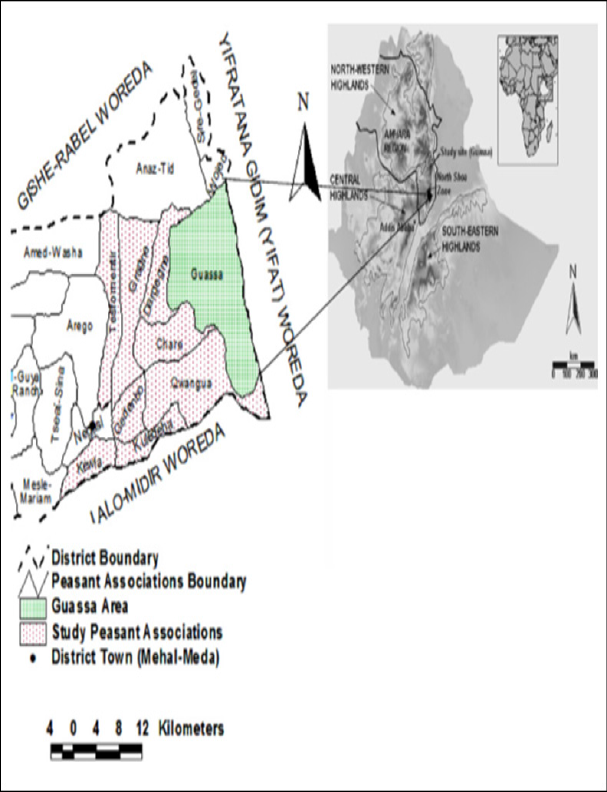

The study was carried out in Guassa Community Eco–Lodge (hereafter GCEL) which was established in 2005, and it belonged to the local people who live in different peasant associations around the Guassa Community Conservation Area.24,25 GCEL is found in the Guassa Grassland Reserve (GGR), also known as the Guassa Community Conservation Area (GCCA). GGR lies between 10°15′–10°27′ N and 39°45′–39°49′ E (Figure 2). The annual rainfall for the area averages between 1,200 and 1,600mm. The area ranges in altitude from 3,200 to 3,700m. The area is part of the Menz–Gera Midir District in North Shewa Administrative Zone, Ethiopia.25 The area is home to numerous endemic wild mammal species, including the iconic Ethiopian wolf, gelada and Ethiopian highland hare.26 Other wild mammal species living in the area include klipspringer, jackal, leopard, spotted hyena, African civets and serval cat. In addition, the endemic bird species in the area include Ankober serin (Serinus ankoberensis), abyssinian catbird (Parophasma galinieri), abyssinian long–claw (Macronyx flavicollis), Ethiopian siskin (Serinus nigriceps), spot–breasted lapwing (Vanellus melanocephalus) and wattled ibis (Bostrychia carunculata).25 The reserve also supports important and endemic plant species including Guassa grass, giant lobelia, erica moorlands and species of Helichrysum and Alchemilla. Other common plant species found in the area include Carex monostachya A. Rich, Carex fischeri K. Schum and Kniphofia foliosa Hochst. The Afro–montane vegetation of the area varies in altitude, and is a key attraction to tourists visiting the area. The GGR is one of the key biodiversity areas in the central highlands of Ethiopia.24,25

Figure 2 Map showing the highland blocks of Ethiopia, and the location of the Guassa Community Conservation Area (GCCA) and the neighboring peasant associations.

Development of the questionnaire survey

We developed a structured questionnaire by considering the various socioeconomic and cognitive variables (e.g. knowledge, beliefs and experience)14,18,27,28 that would likely affect the attitudes of local people towards eco–lodges. Most socioeconomic, knowledge and experience measuring questions were measured in nominal scale and rated, for example, using 3=yes, 2=unsure and 1=no. Age, family size, annual income, and length of residence in the area were measured in continuous quantitative values. Information on previous benefit sharing (i.e. access to and control over eco–lodges), and allocation of land for woodlot plantations was measured in nominal scale and rated using 3=yes, 2=unsure and 1=no. Questions dealing with the attitudes of the respondents towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’, and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ were measured by employing Likert scale and rated using 5=strongly agree, 4=agree, 3=unsure, 2=disagree and 1=strongly disagree through the structured questionnaire survey.29,30 Larger values reflected positive attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’, and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. For the supplementary open–ended questions, the respondents narrated their experiences and knowledge about eco–lodges.

Data collection

The local people in the study site are historically linked to the local biodiversity and knowledgeable about the resources that exist in their environment. More importantly, they can affect the biodiversity because of their direct dependence on the natural resources for fuel–wood, construction materials, sale of wood products and free–range livestock grazing. Hence, the successful conservation of the biodiversity depends on the attitudes of local people who are inherently connected to the local landscape12,16,31 and through their active participation in biodiversity management.

A structured questionnaire comprised of closed– and open–ended questions was developed to examine attitudes of the respondents towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ in the GCEL. The data enumerators conducted the questionnaire survey via direct house–to–house visits. The questionnaires were administered to a total of 165 randomly selected households of which 125 and 40 were around the GCCA and in Mehal–Meda town, respectively. Households for the questionnaire survey were randomly selected from each location through a lottery system based on house identification numbers. The data were collected in May–June 2014.

Independent variables: Independent variables were derived from the following 22 questions: (i) sex, (ii) age, (iii) family size, (iv) level of education, (v) occupation type, (vi) annual income, (vii) livestock ownership, (viii) had enough grazing land, (ix) wanted to keep more livestock than had at present, (x) had a shortage of fodder for their livestock, (xi) length of residence in the area (in years), (xii) history of settlement in the area, (xiii) had the plan to stay in the area in the future, (xiv) private land ownership, (xv) had allocated land for woodlot plantations, (xvi) had a shortage of fuelwood, (xvii) knew any eco–lodge in the area, (xviii) knew that the area was devoid of biodiversity (e.g. forests, wild mammals and birds) before the establishment of the eco–lodge, (xix) knew the trend of the biodiversity of the area after the establishment of the eco–lodge, (xx) knew traditional practices or taboos that restrict local people from destroying the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge, (xxi) got benefits from the eco–lodge, and (xxii) knew that there is a conflict of interest between the eco–lodge and the local people.

Dependent variables: The first dependent variable, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’, was constructed using factor analysis with varimax rotation for data reduction32,33 from four belief–based statements related to eco–lodge and two related to its conservation.

Respondents indicated their level of agreement/disagreement with the following six statements: (i) the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge is the heritage of all Ethiopians, (ii) the presence of the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge is the sign of healthy environment, (iii) the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge has the right to exist, (iv) the qualities and availabilities of the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge would be affected by human and livestock induced disturbances, (v) having eco–tourists visiting the area is a good opportunity to maintain sustainable socioeconomic development through conserving biodiversity, and (vi) the conservation and management of eco–lodge should be supported by the local people. Each of the above statements was measured using 5–point scales (5=strongly agree through 1=strongly disagree). Larger values reflected positive attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’.

The second dependent variable, i.e. attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’, focused on the following two statements: (i) agree to see more number of eco–lodges in the future, and (ii) the areas occupied by the eco–lodge at present would be sufficient enough to maintain sustainable socioeconomic development and biodiversity conservation in the future. Each of the above statements was measured using 5–point scales (5=strongly agree through 1=strongly disagree). Larger values reflected positive attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’.

Data analyses

The raw data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and summarized into tabular format. The belief variables were examined using factor analysis with varimax rotation for data reduction. Cronbach’s alpha (α) was used to test the internal consistency or reliability.34 For the multiple linear regression analysis, we first checked whether there is singularity (i.e. when the independent variables are perfectly correlated and one independent variable is a combination of one or more of the other independent variables) and/or multicollinearity (a condition in which the independent variables are very highly correlated (0.90 or greater)) between or among the different independent variables.14 However, we did not find any singularity and/or multicollinearity between or among any independent variables. Moreover, we also checked the other assumptions of regression, such as linearity, homoscedasticity, heteroscedasticity, homogeneity of variance, and normality. However, we did not find any problem with all the independents variables to meet the assumptions of regression. Multiple linear regression model set at alpha value of 0.05 was used to analyze and predict value of the dependent variables, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. After accounting for multiple comparisons (22 tests per dependent variable) with a Bonferroni correction, P≤0.002 was considered significant. We computed the Bonferroni correction by dividing 0.05 to 22 which is equal to 0.002. This is because Bonferroni correction is a safeguard against multiple tests of statistical significance on the same data falsely giving the appearance of significance.14,17 All the analyses were undertaken using SPSS version 16.

A total of 165 persons responded to the questionnaire survey. Majority of the respondents (81%) were males, and the average age of the respondents was about 39 years with a standard deviation of 13.29. The average family size in a household was 5 persons. Regarding the level of education, some (47%) of the respondents went to elementary school. Most of the respondents (76%) engaged in mixed farming, and the average annual income of the respondents was about 12,500.00 Ethiopian Birr (ETB), which was equivalent to 618.81 USD. The largest percentage (83%) of the respondents had livestock. However, most of the respondents (84%) complained that they did not have enough grazing land. In contrast, majority of the respondents (69%) felt a need to keep more livestock than they had at present. Accordingly, they noted that having more livestock serves as insurance during crop failure. However, the largest proportion (70%) of the respondents ensured that they had a shortage of fodder for their livestock (Table 1).

On average, respondents had lived in the area for about 30 years. Regarding the history of settlement, more than half of the respondents (60%) noted that they had inherited land from their ancestors. Similarly, about 78% and 71% of the respondents planned to stay in the area in the future and noted that they had their own private lands, respectively. However, 71% of the respondents confirmed that they had allocated none of their landholdings for woodlot plantations. So, 68% of the respondents noted that they had a shortage of fuel wood (Table 1).

Variable |

Descriptive Results |

Proportion (%) |

Locality |

Rural area (125 households) |

75.76 |

Mehal Meda town (40 households) |

24.24 |

|

Total sample size (n) |

165 households |

|

Sex |

Male |

81.21 |

Female |

18.79 |

|

Age |

Mean = 38.79 years; SD = 13.29 |

|

Family size |

Mean = 4.78 persons; SD = 1.94 |

|

Level of education |

Illiterate |

1.82 |

Literate |

23.03 |

|

Elementary |

47.27 |

|

Secondary school |

17.58 |

|

Diploma |

4.85 |

|

Degree |

5.45 |

|

Occupation type |

Crop cultivation |

2.42 |

Livestock rearing |

3.64 |

|

Mixed farming |

75.76 |

|

Others (e.g. guarding, daily employment and government jobs) |

18.18 |

|

Annual income |

Mean = 12,500.00 ETB; SD = 10,425.36 |

|

Livestock ownership |

Yes |

83.64 |

No |

16.36 |

|

Had enough grazing land |

Yes |

15.76 |

No |

84.24 |

|

Wanted to keep more livestock than had at present |

Yes |

69.69 |

No |

30.31 |

|

Had a shortage of fodder for their livestock |

Yes |

69.69 |

No |

30.31 |

|

Place of settlement |

Inside the compound of the eco-lodge |

0 |

Outside the compound of the eco-lodge |

100 |

|

Length of residence in the area (years) |

Mean = 30.35 years; SD = 15.49 |

|

History of settlement in the area |

Inherited land from my ancestor |

60 |

Settled by my own interest in search of land |

16.97 |

|

Settled by the state |

7.88 |

|

Bought land |

15.15 |

|

Had the plan to stay in the area in the future |

Yes |

78.18 |

Unsure |

15.15 |

|

No |

6.67 |

|

Had private land ownership |

Yes |

70.91 |

No |

29.09 |

|

Had allocated land for woodlot plantations |

Yes |

28.48 |

No |

71.52 |

|

Had a shortage of fuel wood |

Yes |

67.88 |

No |

32.12 |

|

Knew the presence of the eco-lodge in the area |

Yes |

98.18 |

No |

1.82 |

|

Knew the owner of the eco-lodge in the area |

The government |

66.67 |

The local community |

32.12 |

|

Unsure |

1.21 |

|

Knew the original users of the area before the establishment of the eco-lodge |

The government |

77.58 |

The local community |

20 |

|

Unsure |

2.42 |

|

Knew that the area was rich in biodiversity (e.g. forests, wild mammals and birds) |

Yes |

49.7 |

Unsure |

10.3 |

|

No |

40 |

|

Variable |

Descriptive Results |

Proportion (%) |

Knew that the area was devoid of biodiversity (e.g. forests, wild mammals and birds) |

Yes |

40 |

Unsure |

10.91 |

|

No |

49.09 |

|

Knew traditional practices or taboos that restrict local people from destroying |

Yes |

2.42 |

Unsure |

13.94 |

|

No |

83.64 |

|

The causes for the degradation of the biodiversity before the establishment of the eco-lodge |

Deforestation |

35.76 |

Overgrazing |

38.79 |

|

Illegal settlement |

9.09 |

|

Illegal hunting |

7.27 |

|

Wild fire |

8.48 |

|

Urbanization |

4.24 |

|

Habitat destruction and fragmentation |

29.09 |

|

Agricultural land expansion |

29.09 |

|

The trend of the biodiversity of the area after the establishment of the eco-lodge |

Increasing |

80.61 |

Decreasing |

7.88 |

|

Stable |

2.42 |

|

Unsure |

9.09 |

|

The reason for the increment in the trend of biodiversity after the establishment of the eco-lodge |

Community-based participatory biodiversity conservation |

76.97 |

Strict law enforcement and punishment of those people who involve in illegal encroachment of biodiversity in the compound of the eco-lodge |

61.21 |

|

Got benefits from the eco-lodge |

Yes |

84.24 |

Unsure |

2.24 |

|

No |

11.56 |

|

Knew that there is conflict of interest between the eco-lodge and the local people |

Yes |

17.58 |

Unsure |

7.88 |

|

No |

74.55 |

|

The reasons for such conflict of interest |

Resources competition |

15.78 |

Absence of benefit sharing |

10.91 |

|

Punishment while one is found exploiting resources (e.g. collecting fuel wood, cutting trees, grazing livestock, etc.) in the compound of the eco-lodge without permit |

9.9 |

|

Perceived benefits to the local people due to the presence of the eco-lodge |

Employment opportunities |

63.64 |

Infrastructure development (e.g. roads, clinics, schools) |

26.06 |

|

Wood products (e.g. fuel wood, construction materials) |

45.45 |

|

Source of medicinal plants |

32.12 |

|

Source of fodder for livestock through cut and carry system |

58.18 |

|

Traditional beehive keeping and source of honey |

52.12 |

|

Access to free-range livestock grazing especially during drought periods when there is a scarcity of fodder for livestock |

60.61 |

|

Source of income from visiting eco-tourists by providing guiding service, souvenir selling, horse renting, etc. |

46.06 |

|

Getting free transport during hardship periods such as delivery, sickness, grief, etc. |

16.97 |

|

Aesthetic and recreational values |

68.48 |

|

Thatch |

12.12 |

|

Table 1 Sample characteristics and descriptive results of the study area

Most of the respondents (98%) confirmed that they knew the eco–lodge in the area and 67% of them noted that the eco–lodge belonged to the government. The greatest percentage (78%) of the respondents confirmed that the government was exclusively the original user of the area before the establishment of the eco–lodge. Furthermore, about half of the respondents knew that the area was rich in biodiversity (e.g. forests, wild mammals and birds) before the establishment of the eco–lodge (Table 1).

A majority of the respondents (81%) noted that the trend of the biodiversity after the establishment of the eco–lodge is increasing in the area. For example, 77% and 61% of the respondents argued that the introduction of community–based participatory biodiversity conservation, and claimed that strict law enforcement and punishment of those people who committed illegal encroachment of biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge were the two major reasons for the increment in the trend of the biodiversity after the establishment of the eco–lodge, respectively. In contrast, 84% of the respondents did not know traditional practices or taboos that restricted local people from destroying the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge (Table 1).

Most of the respondents (85%) confirmed that they got benefits from the eco–lodge. Among the most prominent perceived benefits to the local people due to the presence of the eco–lodge include aesthetic and recreational value, employment opportunities, wood products (e.g. fuelwood and construction materials), source of fodder for livestock through cut and carry system, source of medicinal plants, traditional beehive keeping and source of honey, access to free–range livestock grazing during drought periods when there is a scarcity of fodder for livestock, and source of income from visiting eco–tourists by providing guiding service, souvenir selling and horse renting. About 75% of the respondents noted that there is no conflict of interest between the GCEL and the local people (Table 1).

Factor analysis revealed that five out of six statements grouped together to explain about 49% of the variance for the dependent variable, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ with a Cronbach’s alpha (α) value of 0.75. The average of the scores across all respondents was 4.21 (SD=0.79 and range=1–5). The factor analysis further grouped one out of two statements together to explain about 56% of the variance for the dependent variable, i.e. attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodge’. The average of the scores across all respondents was 4.44 (SD=1.05 and range=1–5) (Table 2) (Table 3).

Belief statements |

Strongly Agree (%) |

Agree (%) |

Unsure (%) |

Disagree (%) |

Strongly Disagree (%) |

M (SD)* |

Factor loading score |

The biodiversity in the compound of eco-lodge is the heritage of all Ethiopians. |

54.55 |

30.91 |

8.48 |

5.46 |

0.6 |

4.36 (0.86) |

0.68 |

The presence of the biodiversity in the compound of the eco-lodge |

45.45 |

43.64 |

8.48 |

2.43 |

0 |

4.32 (0.73) |

0.65 |

The biodiversity in the compound of the eco-lodge has the right to exist. |

35.76 |

53.94 |

7.88 |

1.82 |

0.6 |

4.22 (0.72) |

0.69 |

Having eco-tourists visiting the area is a good opportunity to maintain |

20 |

70.32 |

8.48 |

1.2 |

0 |

4.09 (0.57) |

0.75 |

The conservation and management of the eco-lodge should be supported by the local people. |

43.64 |

36.36 |

3.03 |

16.97 |

0 |

4.07 1.07) |

0.69 |

Table 2 Items measuring attitudes towards eco-lodge and its conservation

*Scale values (Strongly agree = 5 through strongly disagree = 1) were used to calculate mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) values, where higher values indicate more positive attitudes towards ‘eco-lodge and its conservation’. Factor loading scores can range from -1 to 1. Loadings close to -1 or 1 indicate that the factor strongly affects the variable. Loadings close to zero indicate that the factor has a weak effect on the variable.

Belief statement |

Strongly agree (%) |

Agree (%) |

Unsure (%) |

Disagree (%) |

Strongly disagree (%) |

M (SD)* |

Factor loading score |

Agree to see more numbers of eco-lodges in the future. |

73.33 |

9.70 |

4.24 |

12.73 |

0.00 |

4.44 (1.05) |

0.75 |

Table 3 Descriptive results for item measuring attitudes towards an increase in number of eco-lodges

*Scale values (Strongly agree=5 through strongly disagree=1) were used to calculate mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) values, where higher values indicate more positive attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco-lodges’.

The multiple linear regression model revealed that several socioeconomic and cognitive variables significantly affected the attitudes of local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’. As revealed from their coefficients, those who were males (ß=0.23), more educated (ß=0.42), had high income (ß=0.54), had enough grazing land (ß=0.42), lived in the area for long time (ß=0 .37), planned to stay in the area in the future (ß=0.34), allocated land for woodlot plantation (ß=0.45), knew the presence of the eco–lodge (ß=0.46), knew that the area was devoid of biodiversity before the establishment of the eco–lodge (ß=0.26), knew the trend of the biodiversity of the area after the establishment of the eco–lodge (ß=0.47) and knew traditional practices or taboos that restrict local people from destroying the biodiversity in the compound of the eco–lodge (ß=0.46) as well as private land ownership (ß=0.54) and previous benefits from the eco–lodge (ß=0.35) significantly had positive attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ (Table 4).

In contrast, those who were older (ß=–0.31), livestock ownership (ß=–0.37), wanted to keep more livestock than had at present (ß=–0.35), shortage of fodder for livestock (ß=–0.36), shortage of fuelwood (ß=–0.38) and knowledge of the conflict of interest between the eco–lodge and the local people (ß=–0.56) significantly had negative attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ (Table 4).

Variable |

Attitude towards ‘eco-lodge and its conservation’ |

Attitude towards ‘an increase in number of eco-lodges’ |

||||

ß |

t |

Pvalue |

ß |

t |

P value |

|

Intercept |

2.49 |

2.91 |

- |

0.74 |

0.44 |

- |

Sex (Male = 2; Female = 1) |

0.23 |

+2.62* |

0.002 |

0.17 |

+2.04* |

0.002 |

Age |

-0.31 |

-2.39* |

0.002 |

-0.27 |

-2.78* |

0.002 |

Family size |

0.04 |

0.47 |

0.643 |

0.09 |

1.23 |

0.721 |

Level of education |

0.42 |

+3.66* |

0.001 |

0.38 |

+4.64* |

0.001 |

Occupation type |

0.01 |

0.11 |

0.913 |

0.08 |

0.14 |

0.843 |

Annual income |

0.54 |

+3.79* |

0.001 |

0.53 |

+4.67* |

0.001 |

Livestock ownership (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

-0.37 |

-3.68* |

0.002 |

-0.48 |

-3.95* |

0.001 |

Had enough grazing land (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

0.42 |

+3.68* |

0.001 |

0.43 |

+3.94* |

0.001 |

Wanted to keep more livestock than had at present (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

-0.35 |

-3.69* |

0.001 |

-0.39 |

-3.95* |

0.001 |

Had a shortage of fodder for their livestock (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

-0.36 |

-3.44* |

0.002 |

-0.39 |

-2.67* |

0.002 |

Length of residence in the area (in years) |

+0 .37 |

+3.59* |

0.001 |

0.38 |

+2.93* |

0.002 |

History of settlement in the area |

0.04 |

0.37 |

0.736 |

0.05 |

1.02 |

0.267 |

Had the plan to stay in the area in the future (Yes = 3; Unsure = 2; No = 1) |

0.34 |

+3.76* |

0.001 |

0.29 |

+2.98* |

0.002 |

Private land ownership (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

0.54 |

+3.79* |

0.001 |

0.57 |

+4.36* |

0.001 |

Had allocated land for woodlot plantations (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

0.45 |

+3.33* |

0.002 |

0.53 |

+3.87* |

0.001 |

Had a shortage of fuel-wood (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

-0.38 |

-3.63* |

0.001 |

-0.34 |

-2.98* |

0.002 |

Knew the presence of eco-lodge (Yes = 3; No = 1) |

0.46 |

+3.29* |

0.001 |

0.38 |

+3.94* |

0.001 |

Knew that the area was devoid of natural biodiversity before the |

0.26 |

+2.99* |

0.002 |

0.39 |

+3.47* |

0.001 |

Knew the trend of the natural biodiversity after the establishment of the |

0.47 |

+3.29* |

0.001 |

0.43 |

+3.26* |

0.001 |

Knew traditional practices or taboos that restrict local people from destroying |

0.46 |

+3.04* |

0.001 |

0.06 |

1.24 |

0.487 |

Got benefits from eco-lodge (Yes=3; Unsure=2; No=1) |

+0.35 |

+2.38* |

0.001 |

+0.59 |

+3.97* |

0.001 |

Knew that there is the conflict of interest between the eco-lodge |

-0.56 |

-3.95* |

0.001 |

-0.36 |

-2.97* |

0.001 |

Table 4 Multiple linear regression modela to predict attitudes towards ‘eco-lodge and its conservation’ b, and ‘an increase in number of eco-lodges’ c. + indicates a positive change in attitude and - a negative change in attitude

aStandardized coefficients were reported; *represents significance at the 95% confidence level;bAdj. R2=0.27, df=21; F=3.06, overall P<0.001; and cAdj. R2

As revealed from their coefficients, those who were males (ß=0.17), were more educated (ß=0.38), had high income (ß=0.53), had enough grazing land (ß=0.43), lived in the area for long time (ß=0.38), planned to stay in the area in the future (ß=0.29) and knew that the area was devoid of biodiversity before the establishment of the eco–lodge (ß=0.39), had private land ownership (ß=0.57), allocated land for woodlot plantations (ß=0.53), knowledge of the presence of eco–lodge (ß=0.38), knowledge of the trend of the biodiversity of the area after the establishment of the eco–lodge (ß=0.43) and previous benefits from eco–lodge (ß=0.59) significantly had positive attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ (Table 4).

In contrast, those who were older (ß=–0.27) and wanted to keep more livestock than had at present (ß=–0.39) , livestock ownership (ß=–0.48), shortage of fodder for livestock (ß=–0.39), shortage of fuel–wood (ß=–0.34) and knowledge on the conflict of interest between the eco–lodge and the local people (ß=–0.36) significantly had negative attitudes towards ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ (Table 4).

Overall, the multiple linear regression model revealed that socioeconomic and cognitive variables had significant effects on the two groups of the dependent variables, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ (27% variance explained), and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ (31% variance explained) (Table 4).

This study was the first attempt to evaluate the attitudes of local people towards GCEL, its conservation and an increase in number of eco–lodges in the GCCA. The study revealed that beliefs of the local people were powerful and consistent predictors of attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ as explained by the variances of the two groups of the dependent variable. Other studies also noted that belief was a consistent predictor of attitudes. e.g.21,23,35,36

Our results revealed that various socioeconomic and cognitive variables significantly affected the attitudes of local people. Generally, the study suggested that local people had positive attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ in the GCCA. For example, a higher percentage of respondents had positive (68%) rather than negative (32%) attitudes towards GCEL and its conservation. Moreover, the larger proportion of the respondents had positive (67%) rather than negative (33%) attitudes towards an increase in number of eco–lodges. In the first place, the GCEC belonged to the local people who reside in different peasant associations around the GCCA.24,25 This could be one of the possible reasons which led to get a result indicating that most of the respondents benefited from the eco–lodge which in turn led them to develop positive attitudes towards GCEC and its conservation.

The local communities also pointed out that viewing GCEL and the associated wild mammals and birds make them more excited than anything else. Local people may value wildlife and its habitats for aesthetic and recreational reasons,12 which are thought to result from historic links between wildlife and traditional tribal culture.31 Similarly, people who feel excitement at the prospect of watching large wild mammals in their natural habitats tend to have positive attitudes towards them.35 Several studies also suggested that previous benefits and values can affect the conservation attitudes of local people. e.g.37–41

The present study had generated a lot of relevant knowledge about eco–lodges. For example, the respondents argued that deforestation, overgrazing, habitat destruction and fragmentation, and agricultural land expansion were the major causes for the degradation of the biodiversity before the establishment of the GCEL (Table 1). While focusing on the attitudes of the local people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’, and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’, the present study contributes to improved knowledge of human dimensions. This may motivate biodiversity conservation managers to include local people while formulating biodiversity conservation strategy and management plan for the GCEL.

Attitudes of local people towards eco–lodges can be positively influenced by increasing their knowledge.17,42 Informing the local communities about the different values of eco–lodges (e. g. recreational, aesthetic, ecological and economic) through conservation education and advocating the need for sustainable utilization may improve the positive attitudes, and increase the support of local people in biodiversity conservation.43,44 More importantly, public awareness programs and conservation education can assist to improve the attitudes of young people towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’.17

Promoting the direct participation of the local people in decision–making and implementation of eco–lodge management can also mitigate potential conflicts and assure long–term public support. By comparing attitudes quantified and presented here in the baseline study, and results from future replication of such kind of studies, researchers can provide relevant information for decision–makers and conservation managers to deal with potential conflict of interests between eco–lodges and the needs of the local people.

The present study suggested that factor analysis explained much of the variances of the two groups of the dependent variable, i.e. attitudes towards ‘eco–lodge and its conservation’ and ‘an increase in number of eco–lodges’ in the GCCA. The multiple linear regression model also revealed that several socioeconomic and cognitive variables significantly affected the attitudes of the local people towards eco–lodge, its conservation and an increase in number of eco–lodges. Generally, local people had positive attitudes towards the GCEL, its conservation and an increase in number of eco–lodges. The study forwarded appropriate management strategies and techniques about eco–lodges that may assist biodiversity managers, conservationists, local communities, private and public sectors in addressing opportunities and challenges for conserving and managing local biodiversity. Other than academic purpose, the findings of this study generated quantitative scientific data for policy–makers and planners that guide them towards better and more informed decision–making for eco–lodge establishment and management that is geared towards socioeconomic development and biodiversity conservation, thereby, achieving the broad goal of poverty reduction.

Based on the findings of this study, the following points that may help ensure the continued support of the local people towards the GCEL can be recommended. For example, introducing and promoting community–based conservation efforts that allow communities to derive economic benefits from ecotourism may promote biodiversity conservation while, at the same time, providing a solution to resource use conflicts around the GCEL. Ecotourism activities can also improve and diversify the income of local people through creating job opportunities, such as tourist guiding services, souvenir selling and horse renting all of which can help make ecotourism economically viable in the GCCA. Moreover, ecotourism is an important and environmental friendly industry to create self–employment opportunities for the local community and also to enhance greater partnership for sustainable management of biodiversity. Previous studies also noted that community support would be dramatically greater if local respondents were to be given economic benefit–sharing schemes as part of the management of natural resources.12,45–47

Construction of additional eco–lodges and improving tourist facilities help promote ecotourism and improve the revenue collected from visiting tourists. An integration of indigenous knowledge with modern conservation approaches in the planning and implementation processes is crucial to improve and promote local participation in conservation and management of eco–lodges. For example, local knowledge not only provides relevant information on the use of the biodiversity, but also contributes valuable information on how to maintain and conserve it. Therefore, effective conservation and sustainable use of the biodiversity in the GCEL need the full involvement of many stakeholders, including the local communities.

The authors would like to thank the following institutions: GCCA, Culture and Tourism Office of Menz–Gera Midir District, and Menz–Gera Midir District Administration Office for their unreserved co–operation in issuing the permit to work on the GCEL and the GCCA. Authors would like to thank the local people residing in Mehal Meda town and different peasant associations around the GCCA for sharing their fruitful ideas and abundant experiences about eco–lodge and its contribution to socioeconomic development, and biodiversity conservation during the questionnaire survey. More importantly, authors are thankful to the leaders of the different peasant associations who coordinated and encouraged the local people to willingly involve and participate in the valuable questionnaire survey. The data enumerators who helped in handling the questionnaire survey via the house–to–house visits are greatly acknowledged.

SAT designed and conducted the field research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. DT interpreted the results and helped in the manuscript writing. Both authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to forward their gratitude to Debre Berhan University for covering all sources of the research funding that helped in the design of the study and collection, analyses, and interpretation of the data and also in writing of the manuscript.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.