eISSN: 2469-2778

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 5

1Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Human Pathology, University of Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence: Manjeeta Baichoo, Seewoosagur Ramgoolam National Hospital, Mauritius, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Nairobi, Kenya

Received: April 09, 2018 | Published: September 4, 2018

Citation: Baichoo M, Musoke R, Githanga J. The spectrum of pathologies found in bone marrow amongst children below 18 years at Kenyatta national hospital, Kenya. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2018;6(5):171-175. DOI: 10.15406/htij.2018.06.00176

Background: Bone marrow examination is a key investigation for both haematological and non–haematological disorders where the bone marrow is involved. Bone marrow examination consists of bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow trephine biopsy which complement each other.

Objectives: To describe the spectrum of pathologies found in the bone marrow of children below 18 years old at Kenyatta National Hospital and to determine the clinical features at presentation observed with the different pathologies found.

Study design and site: This was a descriptive cross‐sectional study carried out from October 2016 to December 2016 at Kenyatta National Hospital.

Method: The registry at the Department of Human Pathology, University of Nairobi, was used to identify the eligible children who had a bone marrow aspirate/bone marrow trephine biopsy during the study period. The children were then traced back to their respective wards. The children were also recruited from the haematology clinic. Consent to use clinical data from their files and their bone marrow aspirate/bone marrow trephine biopsy reports were sought from parents/guardians and assent were obtained from minors aged 8 years and above. The information was collected using a structured questionnaire. The information was then analysed using SPSS software version 23.0.

Results: A total of 90 patients’ files and bone marrow examination reports were analysed. Ages of the patients ranged from 6 months to 18 years. The mean age of the children who participated in the study was 6.70±4.82 years. The peak age group for a bone marrow examination was 1 year to 5 years (43.3%). Males were 52 (57.8%) and females were 38 (42.2%). The main findings were neoplastic disorders (52.4%) followed by reactive marrow (28%) and nutritional anaemia (8.6%). Among the neoplastic disorders, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (34%) was the most common. The commonest clinical presentations observed were pallor (51.2%), fever (32.5%), fatigue (27.5%) and bleeding manifestations (20%).

Conclusion: The main bone marrow pathology found was neoplastic disorder, the majority of which were acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.The most common clinical manifestations found were pallor, fever, fatigue and bleeding manifestations.

Keywords: bone marrow aspirate, bone marrow trephine biopsy, bone marrow pathology, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, reactive marrows

Bone marrow examination is an important tool for evaluating haematological and non–haematological malignancies and non‐malignant diseases. Bone marrow examination is useful, especially where first‐line investigations such as full blood count and peripheral blood film are not sufficient for establishing a diagnosis. A full blood count measures cell counts (red blood cells, white blood cells, the differential counts and platelets), erythrocyte indices, haematocrit (ratio of the red blood cells to the blood volume) and the amount of haemoglobin. A peripheral blood film examination shows the morphology of peripheral blood cells and gives a morphologic diagnosis of various primary and secondary blood and blood‐ related diseases.1 Bone marrow examination is achieved through bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow trephine biopsy. Bone marrow examination and bone marrow trephine biopsy are ideally done together as they give different information. During a bone marrow aspiration, particles from the bone marrow are obtained for microscopic, morphologic evaluations and differential counts. Bone marrow aspirates are especially useful for evaluation of nutritional anaemia, reactive marrow and malignancies. During a bone marrow trephine biopsy, the bone marrow architecture and the structure are assessed.

It evaluates the cellularity, focal lesions such as fibrosis, granulomatous, malignant and metastatic infiltrations.2 Material from the bone marrow can be used for ancillary tests such as immunophenotyping (flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry), cytogenetics (karyotyping), microbiologic cultures and molecular assessment like T‐cell receptor gene rearrangement and B‐cell immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in the diagnosis and follow‐up of T‐cell and B‐cell lymphomas.3‒9 The studies done in Kenya were done at Kenyatta National Hospital in 1990,10 Gertrude’s Children Hospital in 2001,11 Aga Khan University Hospital in 200612 and at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in 2011.13 This study gives a better and more current picture of the BM pathologies in children as the population included in the other studies was children and adults. The findings were compared with other similar international and local studies to detect any change in the pattern of BM pathologies. Moreover, the Nairobi Cancer Registry describes the childhood malignancies but there is no registry that describes the other BM pathologies found in children in Kenya. Data describing the other BM pathologies in children in Kenya is very poor. This study contributes to the knowledge of medical practitioners on the common BM pathologies found in children at Kenyatta National Hospital.

This was a hospital‐based descriptive cross‐sectional study done prospectively over a period of 3 months from October 2016 to December 2016, using hospital records of bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow trephine biopsy reports and clinical data from files of patients. All patients who had a bone marrow examination done as part of their diagnostic workups were recruited from the general paediatric wards and paediatric oncology ward, haematology clinic and adult medical wards. Consent to use the clinical data from their files and bone marrow aspirate/bone marrow trephine biopsy reports for research purposes were obtained from all guardians and assent was obtained from minors of 8 years and above. In addition, children who had a bone marrow aspirate were recruited from the haematology clinic. Consecutive sampling was used for all eligible patients. The files of the patients were reviewed to extract the sociodemographic data such as the age and sex of the child, the clinical features at presentation and the indication for bone marrow examination. The bone marrow aspirate/bone marrow trephine biopsy report of the corresponding patients was then traced. The information collected was then entered in the data collection tool. Descriptive analysis was used to determine the mean, the frequency and the proportion of variables such as age, sex and clinical features at presentation and the prevalence of bone marrow pathologies were computed with 95% confidence interval using SPSS software version 23.0.

A total of 90 participants were enrolled in the study, 52 were males (57.8%) and 38 were females (42.2%). The male to female ratio was 1.3:1. The mean age of the children who participated in the study was 6.70±4.82years. The peak age group was 1year to 5years old at 43.3%. The highest frequency of abnormal bone marrow examination was found in children of 3years old. The youngest child enrolled in the study was 6 months and the oldest child was 18 years old. The sociodemographic data of the participants in the study are summarized in Table 1.

The main indications for bone marrow aspirate/bone marrow trephine biopsy as shown in Figure 1; were suspected leukaemia, found in 27 patients (30%) followed by investigation of cytopenias in 20 patients (22.2%), assessment of remission status during treatment of leukaemia in 18 patients (20%), suspected nutritional anaemia in 13 patients (14.4%), staging of solid tumors in 5 patients (5.6%) and investigation of fever of unknown origin in 3 patients (3.3%). The other indications were: investigation for splenomegaly in 2 patients and abnormal peripheral blood film in 2 patients.

Among the 90 bone marrow examination reports collected, 3 reports were inconclusive, 5 reports were normal and 82 reports were abnormal. The main aetiology of abnormal bone marrow finding was neoplastic disorders in 43 patients (52.4%) followed by reactive marrows in 23 patients (28%). Non‐ malignant haematological disorders such as nutritional anaemia were found in 7 patients (8.5%), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and sickle cell disease were each found in 3 patients (3.7%). Among the nutritional anaemia, iron deficiency anaemia was found in 4 patients (4.9%) and megaloblastic anaemia was found in 3 patients (3.7%). The other bone marrow findings were aplastic/hypoplastic anaemia found in 2 children (2%) and pure red cell aplasia found in 1 child (1%). Among the neoplastic disorders, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was found in 28 patients (34.1%), acute myeloid leukaemia in 6 patients (7.3%), embryonal malignancies (metastasis to the marrow most commonly neuroblastoma part of the group of small round blue tumours) were found in 6 patients (7.3%). The rarer findings were chronic myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplasia. The bone marrow findings are summarized in Table 2.

The distribution of the bone marrow pathologies according to sex was as follows: neoplastic disorders were found in 22 males and 21 females. Among the neoplastic disorders, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was found in 72.7% of males and 57.1% of females. Acute myeloblastic leukaemia was found in 13.6% of males and 14.3% of females. Embryonal malignancies were found equally among males and females. The other neoplastic disorders were found in a minority of children. Non‐neoplastic disorders were found in 39 patients (47.6%) in the study. Reactive marrow was the commonest finding and was most frequently found in males; 16 males (69.6%) and 7 females (3.4%). Other non‐malignant disorders were found in small numbers.

The distribution of bone marrow pathologies according to the different age groups was also investigated. An abnormal bone marrow examination was most frequently found in the age group of 1 year to 5 years at 43.3%. Neoplastic disorders were found in 44.1% of this age group. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was the main haematological malignancy found in the same age group (42.9%). The peak age at which an abnormal bone marrow examination was obtained was 3 years. Among the 12 children who were 3 years old, 7 (58.3%) had a neoplastic disorder. Reactive marrow was the second commonest abnormal bone marrow finding and the most common non‐neoplastic disorder. It was most commonly found in the age group 1 year‒5 years. Among the 23 children with a reactive marrow, the peak age was 1 year old (17.4%).

The main clinical features found among the patients with abnormal bone marrow findings were pallor in 44 patients (51.2%), fever in 26 patients (32.5%), fatigue in 24 patients (27.5%), bleeding manifestations in 18 patients (20%), gastrointestinal tract symptoms, lymphadenopathy and lethargy were each found in 8 patients (10%). The gastrointestinal tract symptoms comprised mainly of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. The central nervous symptoms were mainly convulsions which were seen in 5 patients. Among the 44 patients who presented with pallor, 25 patients (56.8%) had neoplastic disorders and 11 patients (25%) had a reactive marrow. Among the 26 children who had a fever, 13 patients (50%) had neoplastic disorders and 11 patients (42.3%) had a reactive marrow. Among the children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, pallor was found in 13 patients (46.4%), fatigue in 15 patients (53.6%), fever in 10 patients (35.7%) and bleeding manifestations in 5 patients (17.9%). The findings are summarized in Table 3.

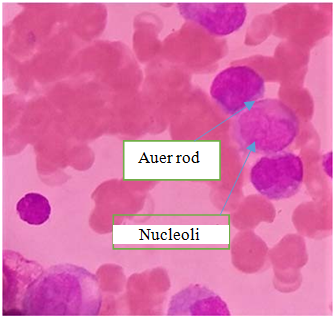

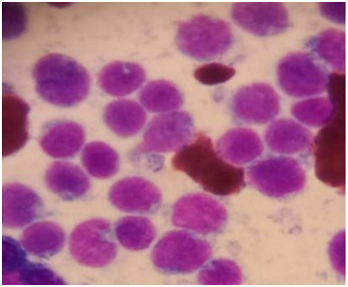

There were 17 patients who were newly diagnosed with leukaemia. Among them, 13 patients (76.5%) presented with anaemia of which 10 patients (76%) had acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Thrombocytopenia was found in 11 patients (64.7%) of which 8 patients (72.7%) had acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukocytosis with abnormal cells was found in 8 patients (47.1%) of which 7 patients (87.5%) had acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Thus the most common full blood count and peripheral blood film findings in newly diagnosed leukaemia patients were a bicytopenia (anaemia and thrombocytopenia) with a leukocytosis comprising of abnormal cells (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2 shows myeloblasts which are large cells with moderate basophilic cytoplasm with azurophilic granules and an Auer rod, single round / oval nuclei, fine chromatin and distinct nucleoli.

Figure 3 shows a hypercellular bone marrow with numerous tightly packed lymphoblasts with scanty cytoplasm devoid of granules, round, irregular, cleaved nuclei, dispersed chromatin and indistinct.

Baseline characteristics |

N = 90 |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

||

Male |

52 |

57.8 |

Female |

38 |

42.2 |

Age |

||

<1 year (1‐11 months) |

4 |

4.4 |

1 year–5 years |

39 |

43.3 |

6 years–10 years |

27 |

30 |

11 years–15 years |

14 |

15.6 |

16 years–18 years |

6 |

6.7 |

Location (Wards) |

||

General paediatric ward |

72 |

80 |

Paediatric oncology ward |

6 |

6.7 |

Medical ward |

10 |

11.1 |

Haematology clinic |

2 |

2.2 |

Table 3 Sociodemographic data

Diseases |

N = 82 |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Neoplastic Disorders |

||

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia |

28 |

34.1 |

Acute Myeloblastic Leukaemia |

6 |

7.3 |

Embryonal Malignancies |

6 |

7.3 |

Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia |

2 |

2.4 |

Myelodysplasia |

1 |

1.2 |

Total |

43 |

52.4 |

Non‐Neoplastic Disorders |

||

Reactive Marrow |

23 |

28 |

Nutritional Anaemia |

7 |

8.5 |

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura |

3 |

3.7 |

Sickle Cell Disease |

3 |

3.7 |

Aplastic/Hypoplastic Anaemia |

2 |

2.4 |

Red Cell Aplasia |

1 |

1.2 |

Total |

39 |

47.6 |

Total |

82 |

100 |

Table 2 Spectrum of bone marrow pathologies among the 82 patients

Clinical manifestation |

N=82 |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Pallor |

44 |

51.2 |

Fever |

26 |

32.5 |

Fatigue |

24 |

27.5 |

Bleeding Manifestations |

18 |

20 |

Lethargy |

8 |

10 |

Lymphadenopathy |

8 |

10 |

Gastrointestinal Tract Symptoms |

8 |

10 |

Splenomegaly |

7 |

8.8 |

Bony Tenderness |

7 |

6.3 |

Central Nervous System Symptoms |

5 |

6.3 |

Hepatomegaly |

4 |

5 |

Jaundice |

2 |

2.5 |

Palpitation |

2 |

2.5 |

Chloroma |

1 |

1.3 |

Table 3 Clinical features at presentation among the children with a bone marrow pathology

This study documented the different spectrum of bone marrow (BM) pathologies both haematological and non‐haematological in the BM aspirates/ trephine biopsies of children at KNH. The main pathology found in the abnormal BM reports was neoplastic disorders (52%) followed by reactive marrow (28%) and nutritional anaemia (9%). Among those who had a neoplastic disorder, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) (34%) was the most common. The BM findings in studies done among children in Pakistan,14,15 Nepal,16 Saudi Arabia7 and US17 were compared to the present study. The two studies from Pakistan showed that aplastic anaemia was the most common BM pathology among children whereas the studies from Nepal,16 Saudi Arabia7 and US18 all showed that neoplastic disorders were the most common finding and acute leukaemias were the most predominant among the malignancies. The latter is very similar to what we found in our study.

In contrast, the study at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) (10) in 1990 was done among patients aged 2 to 75 years over a period of 5 years. It was a descriptive retrospective and prospective study on the role of trephine needle bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of various haematological and non‐haematological diseases. The study showed that aplastic anaemia (27.7%) was the most common finding followed by leukaemia (9.9%) and acute myeloblastic leukaemia (AML) (8.6%) was the predominant type of leukaemia found. But the study was done among adults and children and included 43 patients (42.6%) aged less than 14 years. The BM findings among the children were not clear in the study. Another Kenyan study done at Gertrudes Children Hospital (GCH)11 in 2001 which included children of 2 months to 13 years showed that the most common finding was reactive marrow (40%) followed by malignancies (27%), haematinic deficiencies (12.7%) and ITP (5%). ALL was the most common malignancy encountered. The cause of the reactive marrows was not explored but was attributed to an infective aetiology; mainly malaria at that time. In the current study, the cause of reactive marrow was suspected to be a post‐viral disease in the majority of cases. The other suspected causes of reactive marrow were thought to be due to toxins, chemicals, drug‐induced, post‐haemorrhage and acute on chronic disease. In a study done in the US17 in 2013 among pancytopenic children, bone marrow examination showed parvovirus in 12% of these children. Reactive marrow was the second commonest finding in our study, the causes of which can only be speculated upon but not confirmed as viral studies are not available at KNH. Toxicology testing is also not available at KNH to confirm drug, toxin and chemical‐induced reactive marrow. Another study was done at Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH)12 and evaluated 54 children below 18 years. The most frequent findings in bone marrow examination among those children were megaloblastic anaemia in 6 children (11%), infection including HIV dyspoiesis and iron deficiency anaemia each found in 4 children (7.4%). ALL and AML were equally found in 3 children (5.5%). The study included both children and adults but its main focus was on the pathologies found in adults. The pathologies found in children were described and analyzed as a single group; the age group of less than 18 years. So the BM pathologies among children of different ages were not clear. Another study done at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital13 in 2011 found hypoplastic anaemia (27%) followed by ALL (17%) and megaloblastic anaemia (17%) as the commonest findings. This study was carried out among adolescents and adults. Most of these local studies did not study the children independently from the adult population and so the BM pathologies among the children were not clear. The study that was done at GCH11 among children was done in 2001 and the current study provides a more up to date overview of the BM pathologies found among children.

In the study done at GCH by Githang’a et al.,11 in 2001, the peak age group for a BM pathology was found in the children between 6 to 8 years old but in the current study, the peak age group was 1 year to 5 years. ALL was the most frequent pathology in that age group at 42.9%. The peak age group for ALL in the United States19 is 1‐4 years which are in keeping with what we found in our study.

There was a marked male preponderance in children with a BM pathology as seen in our study and this has been reported in the local study done at GCH by Githang’a et al.,11 and in other international studies from India,20 Pakistan,14 China,21 Saudi Arabia7 and Nepal.16

The most common malignancy encountered in children and adolescents is leukaemia with ALL constituting 30% of childhood tumours worldwide and 75% of cases occur in children below 10 years.19 This is in keeping with our study where ALL was the most common neoplastic disorder found in 71% of children aged less than 10 years.

The clinical presentations observed with the different bone marrow pathologies were described in our study and pallor, fatigue, fever and bleeding manifestations were the main clinical manifestations. The study that was done in Pakistan15 among children found that fever, pallor, body aches, petechial haemorrhages and epistaxis were the most common clinical presentations observed with the bone marrow pathologies. The study from Nepal16 found that fever, weakness, pallor, ecchymosis and bone pain were the most common clinical manifestations among the children with BM pathology. The clinical presentations found in our study are practically similar to the findings of the studies from Pakistan15 and Nepal16 among children with BM pathology.

The differences in the patterns of BM pathologies in different countries may be attributed to genetics, race, diet and environmental exposures such as tobacco, pesticides, fertilizers and benzene among others.22‒24 This could be the basis of another study with a larger sample size to study the diet, the different environmental exposures among others in children with a BM pathology.

The main BM pathologies found were neoplastic disorders (52.4 %), followed by reactive marrow (28%) and haematinic deficiencies (9%). Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was the most common malignancy (34%). The age group 1 year to 5 years was found to have the highest frequency of BM pathology (45%) and the peak age was 3 years old. The main clinical presentations found among the abnormal BM findings were pallor (51.2%), fever (32.5%), fatigue (27.5%) and bleeding manifestations (20%).

A bone marrow aspirate/ trephine biopsy should be considered in children aged 1 to 5 years, presenting with unexplained pallor, fever, fatigue and bleeding manifestations. This study could be the basis of further studies with a bigger sample size and over a longer period of time to investigate the causes of reactive marrows and the effects of different exposures such as diet, environmental factors among others on children with bone marrow pathology.

We acknowledge the invaluable help of the management and staff of the Kenyatta National Hospital, the Haematology laboratory, the Department of Human Pathology and the University of Nairobi administration. Doctor G. Makory for the help she provided in taking the pictures of the bone marrow smears under the microscope.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Baichoo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.