eISSN: 2469-2778

Case Report Volume 4 Issue 1

Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services, Canada

Correspondence: Hanan Gerges, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, 4B1.23 WMC University of Alberta Hospital, 8440-12 St. Edmonton, AB, T6G 2B7, Canada, Tel 1 (780)297-8420, Fax 1(780)407-8599

Received: October 14, 2016 | Published: February 15, 2017

Citation: Gerges H, Nahirniak S. Questionable ABO blood grouping in the setting of solid organ transplantation-a case report and possible resolution techniques. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2017;4(1):27-29. DOI: 10.15406/htij.2017.04.00074

A 52 year-old male who was admitted to our hospital for a penetrating chest trauma, as per our policy, a massive hemorrhage protocol (MHP) was activated to expedite laboratory testing results and provision of blood products. On arrival, no identity or age were known, so 2units of unmatched group O, Rh positive red cells were issued while preparing an unmatched MHP pack which usually contains 6units of group O, Rh positive red cells, 2units of AB plasma +/- one unit of platelets. No specimen was submitted for type and screen as the patient was bleeding profusely from the chest wound. Despite multiple requests, we continued to provide blood products and a sample was received only after transfusing 24packed red cells, 2units of plasma and 1unit of pooled platelets. As expected, both forward and reverse grouping showed mixed field reactions and accordingly interpreted by policy as questionable ABO. Rh typing was clearly positive. The patient continued to be supported during surgery with group O red cells and AB plasma. Unfortunately, during ICU stay, he was declared brain-dead. The family agreed to donate his organs, necessitating accurate determination of the blood group. An attempt was performed using a bone marrow specimen (based on a local project which showed >95% concordance). The reverse typing suggested group A but forward typing was completely negative, likely due to the scarcity of erythroid precursors. As the patient was intubated, it was feasible to obtain a saliva specimen; hoping this patient would be secretor. Luckily, he was and group A was confirmed. Subsequently, the liver and the kidneys were used for transplantation but the heart and lungs were damaged and unsalvageable.

Keywords: ABO blood grouping, trauma, organ transplantation, massive hemorrhage protocol, coagulopathy, hypothermia, hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia

MHP, massive hemorrhage protocol; FUT, fucosyltransferase; HOPE, human organ procurement exchange; RBC, red blood cells

There are a number of definitions used for massive transfusion in the literature, with the most frequently cited being transfusion of 10 or more units of red cells in 24hours. Other definitions used to reflect more dynamic and time-dependent situations include≥5units RBC (red blood cells) in 4hours and≥6units RBC in 6hours.1 The potential complications of massive transfusion are well known2) such as dilutional coagulopathy, hypothermia if not using blood warmers, hypocalcemia/citrate toxicity, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia as well as causing ABO typing discrepancies if ABO specific products are not provided. The latter seemed to be forgotten and/or overlooked when managing massive transfusions. This case is an example of this avoidable laboratory dilemma.

A male patient arrived at our hospital with penetrating chest trauma. As per our policy, an MHP was activated by the emergency physician to ensure that specimens and blood products could be delivered in an urgent fashion. Once the blood bank is notified, the transfusion medicine physician on call and the core laboratory are also notified. No identity or age was available initially. An unmatched MHP was requested; as the patient is an adult male, we issued Rh positive products; each pack contains 6units of group O red cells, 2units of AB plasma +/-1unit of platelets. The patient was transfused with 24units RBC, 2units of plasma and 1unit of pooled platelets with no specimens sent to the laboratory despite requests from the transfusion medicine physician. This ratio was due to the type of trauma (penetrating the heart with copious, uncontrollable bleeding) which did not allow the single blood bank technologist working to keep up with thawing the plasma. A specimen was finally sent to the blood bank for typing at 1hour, 36minutes after admission. During resuscitation, surgery and ICU admission, the patient was transfused 39units of RBC, 9 units of plasma, 2units of platelets, 9units of cryoprecipitate, 2units of fibrinogen concentrate and 2 vials of 25% albumin (200ml) in total.

After receiving the specimen, the forward typing showed mixed field reactions while reverse grouping was suggesting group A. However; the reaction strengths did not meet adequate cut off for confident determination of group A with mixed field secondary to transfusion, hence it was interpreted as questionable ABO. In spite of drastic measures taken; he was declared brain-dead three days later. The family was approached in regard to organ donation, they agreed and signed the consent form. This raised urgent need for more accurate determination of the patient’s blood group.

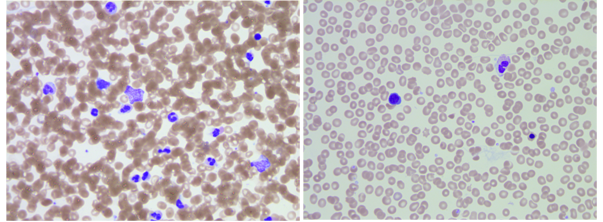

Determination of an accurate blood group is an essential and crucial step for subsequent transplant decisions. The transplant team requested blood bank help to figure out the patient’s blood group. Repeat testing of a peripheral blood sample would be of no value as he was still receiving group O red cells and AB plasma. ABO antigens can be detected on red cells of embryos as early as 5 to 6weeks of gestation.3 The possibility of B antigen expression on erythroid precursors was investigated on bone marrow stem cells.4 A previous local project was done to assess for the possibility of using bone marrow specimens as alternatives to peripheral blood samples. This was based on the fact that some samples were drawn from an intraosseous line in certain situations when an intravenous line is not accessible. The results showed >95% concordance between both specimens (AABB abstract # SP279). A bone marrow aspirate was obtained from the left posterior iliac crest; additional specimens were drawn for viral serology (HIV, Hepatitis B and C viruses). Using the bone marrow aspirate, the reverse grouping showed clear-cut group A but the forward typing was completely negative. Review of H&E stained slides revealed aparticulate aspirate but adequate cellularity. Predominance of granulocytic elements with only rare erythroid precursors were seen on scanning (Figure 1). The absence of sufficient erythroid precursors likely contributed to these reactions. Other plausible explanation is the presence of donor red cells through bone marrow sinusoids and/or peripheral blood contamination.

Red cell genotyping is another way to determine the patient’s blood group. The molecular basis of many antigens of the 30 blood group systems and 17 human platelet antigens is known. In many laboratories, blood group genotyping assays are routinely used for diagnostics in cases where patient red cells cannot be used for serological typing due to the presence of auto antibodies or after recent transfusions. In addition, DNA genotyping is used to support unexpected serological findings.5 However, this is not available locally and a sample has to be sent out to an out of country laboratory and will take at least 7days; if not more. Given the urgent need to collect the organs for donation, this testing method was not further explored. The H antigen is defined by the terminal disaccharide, fucose ɑ 1→2 galactose. Two different fucosyltransferase (FUT) enzymes are capable of synthesizing the H antigen; FUT1 (H gene) and FUT2 (Secretor gene). Secretion of ABH antigens in saliva and other body fluids requires a functional FUT2 gene. FUT2 is not expressed in red cells but is expressed in salivary gland, gastrointestinal tissues and genitourinary tissues. Approximately 78% of all individuals possess the Se gene that governs the secretion of water-soluble ABH antigens into all body fluids except cerebrospinal fluid. These secreted antigens can be demonstrated in saliva by inhibition tests with ABH and Lewis anti-sera.2 Hoping the patient may be a secretor; a salivary sample was sent to the blood bank for testing. Luckily, the secretor status was known for several technologists working at the blood bank laboratory and they were willing to provide salivary samples to help resolve the blood group typing which will ultimately help with the subsequent organ donation (Table 1). Two of the technologists and the author provided a venous sample to be tested for Le antigen and adequate representation of all blood groups. Fortunately, the patient was secretor and the blood group was confirmed to be group A (Figure 2) (Table 2).

Name Initials |

Blood group, Secretor status |

Secretor Status |

F, E |

B Positive, Le (a-b+) |

Secretor |

G, H |

O Positive, Le (a-,b+) |

Secretor |

S, D |

A Positive, Le (a-,b+) |

Secretor |

D, J |

A Positive, Le (a-, b-) |

Non-Secretor |

G, S |

A Negative, Le (a-,b-) |

Non-Secretor |

Y, L (Pregnant female) |

A Positive, Le (a-,b+) |

Variable |

Patient |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Table 1 The ABO blood group, Rh typing and secretor status for each of the controls used

ABO Groups |

Diluted Anti-sera Used |

Indicator RBCs Used |

Results |

|

Saline Control |

Anti-A |

A2 |

4+ |

|

Saline Control |

Anti-B |

B |

4+ |

|

Saline Control |

Anti-H |

O |

2+ |

|

Pos. Control F, E |

B |

Anti-B |

B |

0 |

Pos. Control G, H |

O |

Anti-H |

O |

0 |

Pos. Control S, D |

A |

Anti-A |

A2 |

0 |

Neg. Control D, J |

A |

Anti-A |

A2 |

1+ |

Neg. Control G, S |

A |

Anti-A |

A2 |

0 |

Variable (Pregnant) Y, L |

A |

Anti-A |

A2 |

0 |

Patient’s Saliva |

A |

Anti-A |

A2 |

0 |

Patient’s Saliva |

B |

Anti-B |

B |

4+ |

Patient’s Saliva |

O |

Anti-H |

O |

0 |

Table 2 Tubes were numbered 1 through 12 as indicated in the table above therefore the pictures below also have the tubes from left to right as 1 through 12. Tubes 1, 2, 3 and 11 clearly show strong agglutination. Tube 7 was a very weak positive and not noticeable in the picture

After blood group confirmation, the transplant team were able to coordinate organ donation; the liver and the two kidneys were transplanted in three patients through the HOPE (Human Organ Procurement Exchange) program. In the follow up of this case, debriefing sessions with the trauma team and transfusion medicine were performed to facilitate improved specimen and blood product provision as well as communication between teams. Also, trauma team coordinator will explore venues for funding so that two technologists will be working in night shifts.

Massive transfusions are frequently encountered in trauma patients. It is important to collaborate with the transfusion medicine physicians and have clear communication early on. The uncontrollable bleeding patients can cause chaos and no question that the clinical team focus on urgent blood products. However, it is important as well to send a specimen to the blood bank to help providing group specific products and better manage their inventory. Although venous specimens are preferred, in the setting of an MHP with compromised venous access, alternate specimens for ABO determination can also include shed blood or intraosseous specimens submitted in EDTA tubes with proper labelling to reflect the type of the specimen.

The authors would to like to thank the technologists working at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for their valuable time and effort to resolve this case; in particular Arlene Kryschuk who performed the saliva secretion testing.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Gerges, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.