eISSN: 2469-2778

Case Report Volume 10 Issue 4

1Deaprtment of Hematology, University of Medical Sciences of Sancti Spíritus, Cuba

2Deaprtment of General Medicine and Hematology, University of Medical Sciences of Sancti Spíritus, Cuba

3Deaprtment of Neonatology, University of Medical Sciences of Sancti Spíritus, Cuba

Correspondence: Ariel Raúl Aragón Abrantes, Specialist in Hematology, Provincial University Pedaitric Hospital “José Martí”, Sancti Spíritus, Cuba

Received: December 14, 2022 | Published: December 23, 2021

Citation: Abrantes ARA, Saez LES, Aguiar DH. Primary immune thrombocytopenia and cytomegalovirus infection About a case. Hematol Transfus Int. 2022;10(4):107-108. DOI: 10.15406/htij.2022.10.00291

Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired coagulation disease characterized by a decrease in platelets below 100 x 109/L in the absence of other causes of thrombocytopenia and that may be preceded by viral processes or vaccination. A 16-year-old male adolescent who presented a febrile syndrome was diagnosed as part of the studies as an infection by cytomegalovirus, later he began to present purpuric hemorrhagic manifestations on the skin and mucous membranes, for which a medulogram was performed and the diagnosis of Primary ITP was made. Conclusions: an adolescent who developed a TIP after cytomegalovirus infection, requiring treatment with steroids and valganciclovir for its management.

Keywords: Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia, Cytomegalovirus

Primary immune thrombocytopenia (PIT) is an acquired hemorrhagic disease characterized by decreased platelet count below 100 x 109/L, excluding other causes of thrombocytopenia.1 In children, it usually occurs preceded by a viral infection two or three weeks prior to diagnosis, and with a generally self-limiting evolution.1 Within these viral processes, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis C virus, parpovirus among others have been described.2

A 16-year-old, male patient with diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection, after then he developed a primary ITP, for which he required simultaneous treatment for both pathologies. The objective of the presentation is to describe the characteristics and clinical evolution of this patient.

A 16-year-old male adolescent with a history of a prolonged febrile syndrome, in the several studies to determine its etiology, including TORCHS studies, resulting positive for cytomegalovirus infection, confirmed by Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with spontaneous improvement of fever and no other physical examination abnormality. In his subsequent evolution, he began to present purpuric-hemorrhagic manifestations on the skin and mucous membranes, with the appearance of petechiae disseminated throughout the body, more frequent in the lower limbs, and the presence of moist purpura in the oral cavity. Complementary is carried out verifying:

Hct: 0.39 percent

Leukocytes: 11.9 x 109/L

Segmented: 0.36%

Lymphocytes: 0.60%

Reactive lymphocytes: 0.04%

Platelet count: 3 x 109/L

Due to these results and the history of the febrile syndrome, we was decided to carry out the medulogram, concluding as peripheral thrombocytopenia, ruling out other causes of thrombocytopenia, so it was finally concluded as a primary ITP, for which we was decided to start treatment with intravenous (IV) gammaglobulins at 400mg/kg/day for 5 days, with no response to it (platelets: 8 x 109/L at the end of treatment) and bleeding manifestations (gingival bleeding), for which a second cycle of treatment with steroids is performed (dexamethasone 40mg/m2/day x 4 days ) achieving hematological recovery but with a relapse of the platelet count in less than 4 days after the end of the treatment, for which the treatment with valganciclovir was decided at 16mg/Kg/day orally (PO) and a second cycle of dexamethasone was repeated, achieving full remission.

Primary ITP is defined as an isolated thrombocytopenia of less than 100 x 109/L of autoimmune origin in the absence of other recognizable pathologies, with an approximate incidence in pediatrics of 1.9 to 6.4 cases/100,000 per year.3 It can be classified according to temporality as recently diagnosed in the first three months of diagnosis, persistent from 3 to 12 months after diagnosis, and chronic for more than a year. It is considered severe when there is active bleeding that requires treatment, refractory to severe Primary ITP after splenectomy, while those who need continuous steroid treatment to maintain platelets above 30 x 109/L and/or prevent bleeding are classified as corticosteroid-dependent.4

This adolescent can be classified as newly diagnosed because he is in the first three months of the onset of symptoms, maintaining manifestations mainly on the skin and mucous membranes. The main pathophysiological mechanism is the alteration of the immune system with dysregulation of T lymphocytes causing both a cellular and humoral response against platelet and megakaryocytic antigens.5 Therefore, thrombocytopenia is caused by anti-platelet glycoprotein antibodies and by cytotoxicity mediated by CD8 T cells, which also act on megakaryocytes, inhibiting platelet synthesis. It has also been suggested that there are low levels of thrombopoietin and that some antibodies may inhibit platelet activation instead of causing its destruction.6 In paediatrics patients, this alteration of the immune system is generally preceded by a viral process or previous vaccination 1 to 3 weeks before.7 In our patient, the diagnosis of Primary TIP was preceded by a confirmed cytomegalovirus infection, beginning with the purpuric manifestations one week after the improvement of the febrile symptoms.

Human CMV is a virus that belongs to the herpesviridae family, it has a linear double-stranded DNA genome with approximately 120 to 250 kilobase pairs, considered an opportunistic pathogen with a wide distribution worldwide, it can manifest itself in different ways, from asymptomatic (generally in immunocompetent patients), with symptoms similar to mononucleosis, another form of presentation is congenital infection, it may also have manifestations of encephalitis, ventriculitis, myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, uveomeningeal syndromes, among others.8–10

Viral processes can cause thrombocytopenia by various mechanisms, since the virus can invade the bone marrow affecting megakaryocytes, viral antigens can produce platelet aggregates that will be destroyed by the spleen, and can also cause vasculitis that causes microangiopathic thrombocytopenia and, as has been described in the Primary TIP and occurred in this case, an immunological mechanism can be triggered between 7 and 10 days after the start of the process.2 The appearance of a severe purpuric manifestations is characteristic in pediatric patients, with affections of the skin and mucous membranes, with the presence of petechiae frequently in areas of greater pressure, wet purple (predictor of more severe bleeding), ecchymosis, epistaxis, menorrhagia and in some cases more severe bleeding such as gastrointestinal or central nervous system (CNS).11,12

Our patient manifested as described in the bibliography with manifestations of petechiae disseminated throughout the body, more frequent in the lower limbs, he also presented wet purpuras on the oral mucosa and gingivorrhagia, mainly after brushing. The diagnostic criteria for Primary ITP are: isolated thrombocytopenia with platelet counts below 100 x 109/L, intact or hyperplastic megakaryopoietic system, granulopoietic and erythropoietic system without alterations, excluding secondary causes of thrombocytopenia.1

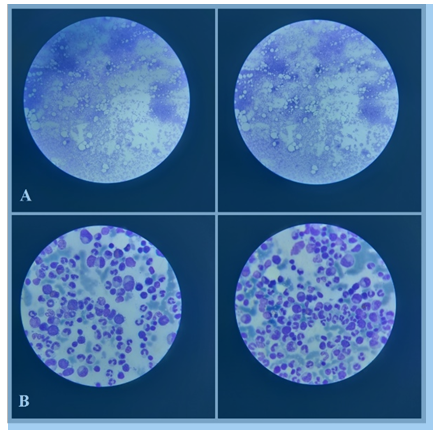

We performed the medulogram on the patient where we observed a hyperplasia of the megakaryopoietic system with the presence of 8-10 megakaryocytes per field, with integrity of the other systems (Figure 1). First-line treatment is fundamentally based on steroids therapy and the use of IV gammaglobulin, while splenectomy or the use of other agents such as rituximab can be performed as second-line.13

Figure 1 Bone marrow. (A) Hyperplasia of the megakaryopoietic system, (B) Normal granulopoietic and erythropoietic system.

In this case, we decided to start treatment with IV gammaglobulins and, as he was no response, other first-line treatments were used, in this case dexamethasone at 40mg/m2/24 hours. In addition, we were decided to associate valganciclovir as a treatment for cytomegalovirus, thus achieving complete remission of the patient.

The patient in the clinical case presented an infection by cytomeglovirus and later he developed a Primary ITP, for which, for its correct management, he required the administration of immunosuppressive therapies with IV gammaglobulins and dexamethasone, associated with antiviral therapy with valganciclovir.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

©2021 Abrantes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.