eISSN: 2469-2778

Case Report Volume 4 Issue 4

1Department of Hematology, AMRI Hospital, India

2Senior Registrar, Apollo Gleneagles hospital, India

Correspondence: Neelesh Jain, MD, Associate Consultant, Hematology, Haemato-Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplantation, AMRI Hospital Mukundpur, Kolkata, India, Tel 919874592738

Received: September 18, 2016 | Published: May 11, 2017

Citation: Jain N, Sarda P, Chakrabortty J. Management of a case of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with salt loosing nephropathy. Hematol Transfus Int J. 2017;4(4):109-11 DOI: 10.15406/htij.2017.04.00091

In lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) also known as Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia (WM) renal disease is less common than in multiple myeloma.1–3 WM accounts for about 5 % of all malignant B-cell disorders associated with a monoclonal protein spike in the serum or urine, and about half of patients who have a monoclonal Immunoglobulin M (IgM) spike in the serum have this disorder.4 Plasma cell dyscrasias often are associated with kidney diseases due to the production of monoclonal immunoglobulin but with a diverse set of pathologic renal patterns. While many patients undergoing a renal biopsy and showing a cast nephropathy have multiple myeloma (MM), kidney involvement associated with pathological immunoglobulin light chains and lymphoma is rare. Thus a therapeutic approach that decreases light chain production appears to be warranted in such patients.5

Keywords: plasma cell dyscrasias, lymphoma, light chain production, hypercellularity

LPL, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; IgM, immunoglobulin M; MM, multiple myeloma; WM, waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia; SPE, serum protein electrophoresis; NS, nephrotic syndrome; NHLs, non-hodgkin lymphomas

MM is very commonly associated with renal failure. A renal biopsy in such patients shows a cast nephropathy but the association of cast nephropathy with lymphoma is quite rare.5 We present a patient with a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma along with salt losing nephropathy illustrating the relation between light chain deposition and renal dysfunction which often presents as a diagnostic challenge.

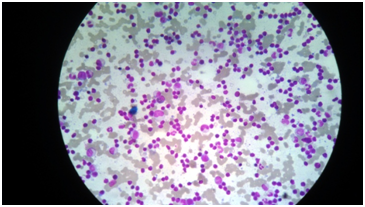

A 57 year old non diabetic but hypertensive male was referred to us with fever, weight loss and low backache. On examination he was found to have mild splenomegaly (2cm) and small (pea sized) right inguinal lymph node. His blood revealed Hb level of 8.4 gm/dl, total count of 5300/cumm with lymphocytosis (65%) and a platelet count of 1.1 lacs/cu mm. Direct coombs test was positive. Total protein was 8.5mg/dl with globulin of 2.9mg/dl, other biochemical parameters were within normal limit. Serum protein electrophoresis (SPE) and serum free light chain assay revealed kappa light chain 6.31 mg/dl and lambda light chain 0.49 mg/dl with kappa lambda ratio of 12.88 which was suggestive of kappa myeloma disease. His bone marrow aspirate shows hypercellularity with medium sized atypical lymphoid cells with clumped chromatin. Some lymphoid cells with eccentric nuclei noted along with 3% plasma cells (Figure 1). Bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow diffusely infiltrated by small to medium size round to elongated lymphocytes with dense chromatin suggestive of a lympho-proliferative disorder (Figure 2). Flow Cytometric analysis on marrow aspirate revealed 44% cells in the lymphoid region out of 100,000 gated events. The cells were an admixture of about 38% B cells, 54% T cells & 8% NK cells.

Figure 1 N=57; Epidemiological distribution of the pathological fractures, traumatic fractures, and nonunion.

For further classification, immunohistochemistry on trephine biopsy revealed CD20, kappa and CD138 positivity. And MYD 88 positivity finally classified the lymphoma as lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. After confirmation of the diagnosis he was put on; Rituximab (375mg/m2), Bendamustine (120 mg/m2) and Bortezomib (1.3mg/m2) therapy for 6 cycles of 28 days each. After completion of 6 cycles he was given maintenance rituximab for 1 year at 2 monthly interval. During this phase of maintenance chemotherapy he developed salt loosing nephropathy with serum sodium reduced to 117mmol/l and nephrotic range proteinuria (6 gm/L). Initially renal biopsy was considered but could not be done because of the lack of justification as other renal functions were absolutely normal. This associated hyponatremia was subsequently diagnosed as salt loosing tubulopathy or nephropathy and it was adequately managed with oral sodium chloride tablets. Proteinuria was managed with monthly rituximab therapy for about 6 months considering its cause as renal parenchymal deposition of immunoglobulin. Patient is doing very well now and started his routine office work as well.

The incidence of renal complication in WM is very less compared to the incidence in those of myeloma patients. This is probably due to the rare occurrence of Bence-Jones proteinuria in WM which may also explain why tubular casts and so called ‘myeloma kidney’ are rare in WM.6 In WM renal disease is usually caused by IgM deposits along the glomerular basement membrane, infiltration of the interstitium with lymphoid cells or amyloidosis.7 In our patient, renal disease presented as renal failure with a slight proteinuria with kappa & lambda light chains on immunoelectrophoresis. Renal involvement in WM presents as usually a mild non-selective proteinuria and microscopic haematuria. Massive proteinuria and a nephrotic syndrome may develop and in most cases is caused by amyloidosis.7 Bence Jones proteinuria is present in 80-90% of the patients, but the quantity is much smaller than in MM. Cryoglobulinemia and acute renal failure are rare in WM. In most cases renal failure is chronic, but due to inadequacy of follow-up data, not much is known about the course of renal failure in WM.7 The two major classes of light-chain proteins, are kappa and lambda, which are being synthesized in bone marrow plasma cells. Each major type can be further classified by the use of appropriate antisera into several subtypes, four kappa and five lambda.8

Kidney is the major site of metabolism of light-chain proteins. Even though the complete Ig (molecular weight1 60,000 to 900,000) and heavy chains do not pass through the normal glomerular filtration barriers, the small light chains can freely pass through. These filtered proteins, reabsorbed by proximal tubular cells are then catabolized by lysozymal enzymes. Normally, this highly efficient process leaves only a minute amount of light-chain protein, which then appears in the urine. Thus, metabolism depends on the function of the proximal tubular cell and damage to these cells can result in increased excretion of light-chain proteins in the urine. In diseases in which the production of light-chain proteins is markedly increased, the ability of the proximal tubules to reabsorb all the filtered protein is exceeded, and light-chain proteins appear in the urine in high concentrations in this setting as well.8

Light-chain proteinuria is common in WM; its prevalence ranging from 30% to 40%. Patients with WM have a plasma cell dyscrasia and they produce IgM paraproteins. As IgM has a tendency to form a pentamer, patients with the disease are much more likely to develop high serum viscosity than are patients with MM. The overall prevalence of Nephrotic Syndrome (NS) in Hodgkin disease is about 0.4% and is even lower in non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs).8 Both idiopathic and malignancy-associated NS are thought to be mediated by a soluble permeability factor, still unidentified, which causes loss of selective capillary permeability and allows albumin and other negatively-charged molecules to cross the glomerular barrier. In lymphoma-associated NS, the permeability factor is supposed to be paraneoplastic in origin.9

Lymphoma-associated kidney involvement occurs by a variety of mechanisms, which differ widely in prevalence and clinical presentation. In conclusion, we described a patient with WM and Salt losing nephropathy caused by IgM deposits. Treatment with chemotherapy in our patient resulted in an improvement to a normal renal function and disappearance of proteinuria.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Jain, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.