eISSN: 2576-4497

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

1Medical Student, University of Ribeirão Preto, Brazil

2Phd in Biotechnology, University of São Paulo, Brazil

3Medical Student, Nove de Julho University, Brazil

4Medical Student, Central University of Paraguay, Paraguay

5Physiotherapist, Nove de Julho University, Brazil

6Physiotherapist Student, University of Ribeirão Preto, Brazil

7Medical Student, University of Southern Santa Catarina. Tubarão, Brazil

8Medical Student, University of the Integration of the Americas, Paraguay

9PhD in Medical Sciences. Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence: Thiago Augusto Rochetti Bezerra, Medical Student, University of Ribeirão Preto, Guarujá, São Paulo, Brazil

Received: July 24, 2024 | Published: August 6, 2024

Citation: Malaquias DTM, Furtado DC, Silva ACCD, et al. The terminality of life and the role of health professionals and their respective palliative care protocols. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2024;7(3):84-87. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2024.07.00245

Introduction: Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families in the face of life-threatening illnesses, relieving suffering and treating pain and other physical, psychosocial and spiritual symptoms. In order to minimize pain and suffering in this dying process, it has become necessary to implement palliative care protocols in ICUs. Objectives: The aim of this study was to carry out an up-to-date literature review on the terminality of life and the role of health professionals and their respective palliative care protocols.

Material and methods: The methodology used was a literature review. Results: The importance of treating a terminally ill patient was noted, many of the curative/restorative measures may constitute futile treatment, such as parenteral or enteral nutrition, administration of vasoactive drugs, renal replacement therapy, institution or maintenance of invasive mechanical ventilation and even hospitalization or permanence of the patient in the ICU.

Conclusions: Through a review of the literature, this study found that the provision of palliative care to seriously ill patients and their families must follow the wishes of the patient themselves, their relatives and the multi-professional team. With regard to the patient's own wishes, the autonomy of the individual and the principle of non-maleficence must be respected, prioritizing decisions by consensus within the maximum certainty of irreversibility. Thus, the team's decision must be preceded by the consent of the patient or their legal representatives, recorded in the medical records.

Keywords: palliative care; ICU palliative care protocols; relief of suffering, pain management

Palliative care approaches can alleviate the pain not only of the patient but also of their family, whether it is physical, emotional or spiritual.1 In the terminal phase, when the patient has little time to live, palliative care becomes a priority to ensure quality of life, comfort and dignity. The transition from care aimed at healing to care with palliative intent is a continuous process, and its dynamics differ for each patient.2 According to Santos, members of the multi-professional ICU team become distressed by doubts about the real meaning of life and death. For the author, modern medicine underestimates the comfort of the terminally ill, imposing on them a long and painful agony, postponing their death. In order to minimize pain in this dying process, it has become a necessity to implement palliative care protocols in ICUs.

The aim of this study was to carry out an up-to-date literature review on the terminality of life and the role of health professionals and their respective palliative care protocols.

The methodology used was a literature review. A literature review is a meticulous and comprehensive analysis of current publications in a particular area of knowledge. This type of research aims to put the investigator in direct contact with the existing literature on a subject. The research was carried out by means of an electronic search for scientific articles published on the Scielo (Scientific Electronic Library Online) and Lilacs (Latin American Health Sciences Literature) and Pubmed websites. The health terminologies consulted in the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS/BIREME) were used: the end of life and the role of health professionals and their respective palliative care protocols. The inclusion criteria were: original article, published in Portuguese and English, freely accessible, in full, on the subject, in electronic format, totalling 20 articles.

Before recommendations and suggestions could be made for topics to be researched, it became necessary to define commonly used terms. According to Aslakson et al.3 the approach to patients and their families is carried out by a multi-professional team made up of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, nutritionists, social workers, psychologists, speech therapists and pharmacists, in activities directly linked to biopsychosocial needs. However, administrative staff, drivers, chaplains, volunteers and caregivers also accompany and support family members and staff in the patient's well-being. According to Almeida & Marcon,4 a terminally ill patient is a patient considered to be in a condition when their illness, regardless of the therapeutic measures adopted, will evolve inexorably towards death. According to the World Health Organization, palliative care is the active and comprehensive care provided to patients with progressive and irreversible illnesses and their families. In this care, it is essential to control pain and other symptoms by preventing and relieving physical, psychological, social and spiritual suffering.

For Coelho & Yankaskas,5 palliative actions are defined as therapeutic measures, without curative intent. At this stage, care should be provided to family members and patients in an acute phase of intense suffering, in the final stages of a terminal illness, in a period that may precede death by hours or days. Fraga et al.6 highlight futile treatment as any intervention that does not meet or is inconsistent with the objectives proposed in the treatment of a particular patient.

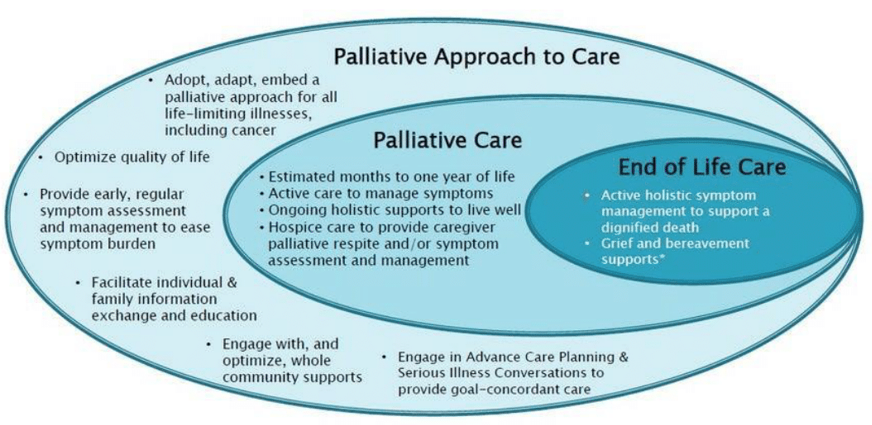

According to Costa Filho et al.7 when a cure is not possible, it is necessary to take care of the patient's well-being, so that a dignified and peaceful death is possible. Palliative care should be carried out by a multi-professional team in agreement with the patient, their family or legal representative. Once defined, palliative actions should be clearly recorded in the patient's clinical file (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Differences between palliative care and end-of-life care.8

The Figure 1 shows that palliative care is an approach to care that supports the clinical, emotional and spiritual needs of individuals and their families who are facing a life-limiting illness. Palliative care and a palliative approach to care focus on comfort and support for the person and family, assist in making plans and decisions for the journey ahead and optimize quality of life. It is important to share health care wishes and goals with loved ones, doctors and other health professionals. For Fraga et al,6 many of the curative/restorative measures can constitute treatment, such as: parenteral or enteral nutrition, administration of vasoactive drugs, renal replacement therapy, institution or maintenance of invasive mechanical ventilation and even hospitalization or permanence of the patient in the ICU. The decision on palliative treatment, according to Fraga et al,6 requires those responsible for the ICU to inform the institution's management (Ethics Committee, Bioethics, etc.). It is necessary to prioritize communication between the healthcare team, patients and their families, as the lack of communication is one of the main barriers that cause conflicts in the treatment of terminally ill patients in the ICU.

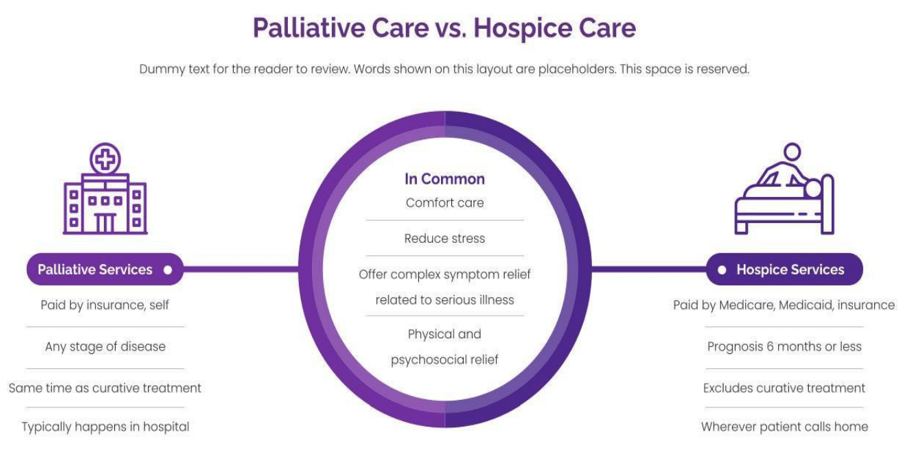

It is important to note that this can lead to an irreversible worsening of the symptoms of a chronic illness or acute event. The multidisciplinary ICU team must continually reassess the clinical evolution of their patients, which includes redefining treatment objectives and considering the provision of palliative care when treatment no longer offers benefits.6,7 For Kelley et al.9 in some cases death is inevitable and delayed only with high psychological, social and financial costs for all parties involved in this process (patient, family and health professionals). In many cases, further treatment does not achieve the patient's treatment goals. This situation is becoming more frequent, as today 20% to 33% of patients die in the ICU. The Figure 2 shows the end-of-life care service that is offered to each patient wherever they are. Patient wherever they are. Regarding decision-making, the World Health Organization (2023) concluded that only 14% of patients worldwide who need palliative care receive this type of attention. Many of them are treated in the ICU. Due to the wide availability of life-support technologies in the ICU, the coexistence of palliative care in the ICU is a challenge. Thus, current intensive care must be balanced between palliative and curative measures in critical conditions. In addition, Mendes et al.11 cite that the primary purpose of the ICU should not only be to promote aggressive treatment; it should also help patients and families make wise end-of-life decisions. It is therefore mandatory that intensivists receive training to fulfill this role, which is current and fundamental.

Figure 2 Palliative Care and Hospice Care for Terminally Patients.10

Today, the presence of a palliative care service is an accreditation element adopted as necessary by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and used to choose the best medical centers in the United States. Palliative care in the ICU supports patients and their families and can provide a more comfortable environment, better healing and greater awareness of the end of life. In Brazil, legislation and codes of ethics have recently been amended. The Brazilian constitution states that human dignity in death is a primary right, which aligns with the withdrawal of life support. The interpretation of the law assumes that no one, even in a life-threatening situation, can be forced to accept medical treatment or surgery.

Resolution number 1.805/2006 of the Federal Council of Medicine (CFM) supports the suspension of futile treatments for incurable terminal illness, if accepted by the patient or their legal representative. The advance directive of will (CFM resolution 1.995/2012) is a legal and ethical document that allows health professionals to respect the will of a particular person. This document allows someone to make their own choices regarding future treatment, such as receiving or refusing treatment, if they are unable to communicate or express their will. This topic has recently attracted the attention of the Brazilian medical community, and several national and international articles have been published on palliative care and terminal illnesses in the ICU. Regarding communication, Fonseca & Mendes Junior,12 mention that in the ICU, communication is a process that involves the perception of the environment and the working climate, including the non-verbal communication of the multi-professional team, up to the doctor/patient and family interaction. Involved in the ICU communication process are patients, their families or anyone close to them, doctors, nurses, psychologists, religious people and other members of the multi-professional team. The evaluation of the channels of the process, the main barriers to communication, the elements and strategies of good communication must be pointed out, recognized and combated, or followed, so that the process develops satisfactorily.

According to Silva et al.13 the following are considered critical communication process channels:

Noise: is interference that is foreign to the message, making communication less effective. It means any unwanted disturbance or noise. Noises such as loud conversations, ringing telephones, equipment, etc.

Omission: can occur when the receiver does not have sufficient capacity to grasp the entire content of the message and only receives or passes on what they can grasp.

Distortion: can be caused by people's so-called "selective perception": each person consciously or unconsciously selects the stimuli and information that interests them and starts to selectively perceive them, omitting other information.

Overload: this occurs when communication channels carry a greater volume of information than they are able to process. Overload causes omission and contributes greatly to distortion. According to Soares et al.14 there is evidence that communication between ICU staff and patients/family members is inadequate. Recent studies have shown that patients' relatives are dissatisfied with the quality of this communication. It has been suggested that the quality of communication between the ICU team and the family is directly related to the satisfaction of family members with the treatment. Communication with patients and their families can be difficult in the ICU, due to the severity of the illness, medical complications, the high risk of death and the family's limited medical knowledge. It is not often that intensivists lead discussions about advance directives or care plans in hospitals. Efforts to improve the quality and quantity of these discussions (when the patient is stable) improve ICU efficiency, reduce the burden of patient care during the end-of-life period, and reduce the burden on families and medical care providers.15

According to Silveira et al.16 some intensivists hesitate to communicate when problems, therapeutic options and prognoses are not well defined. Research data on interactions with family members in the ICU is limited. A systematic approach to daily communication can be effective in this type of situation. The approach described below has been effective in several major centers. Moritz et al.17 points out that good communication is an essential part of medical practice in the ICU. Standardized practices provide a basis for improving patient care in most situations. The key elements are: identifying the people on the medical team and the family (usually the medical decision-makers); establishing a regular schedule for daily meetings; defining the main problems initially and as clinical progress occurs; identifying and respecting the patient's preferences regarding treatment; and communicating concisely and consistently.

Clary,18 mentions that after the initial assessment and stabilization of the patient, the first meeting with the patient's relatives is essential to find and identify the main decision-maker, report on the initial assessment and diagnosis, as well as therapeutic plans, assess the existence of advance directives and plan subsequent meetings. Many people have no experience of dealing with family members of a critically ill patient. It is useful to explain the ICU's standards of organization and care, as well as clarifying the roles of the members and the hierarchy of the team. Scheduled meetings, for example immediately after each doctor's visit, are useful for everyone. A responsible visitor for each patient can help reduce ambiguity and confusion. This first meeting is usually the longest and sets expectations for future meetings. A problem-oriented approach, including its solution, worsening and new events, helps to organize the meetings. If there is no directive, family members can be guided to consider what the patient's choice would be if they were fully conscious in those circumstances.

Clinical progress in the ICU can guide subsequent discussions on the situation, future therapeutic needs or palliative care options. Family members appreciate knowing that their loved ones have received the best therapeutic options and that their preferences regarding care are respected. This approach is effective whether the outcome is complete recovery, death in the ICU or transition to exclusive palliative care.11 According to Aslakson et al.3 a person should die with dignity. To do this, the healthcare team must prevent harm and care for the patient during their end of life. For Coelho & Yankaskas,5 a common therapeutic approach could be defined based on prior discussions between the multidisciplinary team in the ICU, including the team providing primary care and the different specialties involved in patient care. This helps to avoid feelings of uncertainty for patients and their families. As there are often multiple specialties involved, such as clinicians, surgeons, oncologists, intensivists, palliative care specialists, the risk of misunderstandings is high. This proactive approach to communicating palliative care to patients and their families has reduced the length of stay in the ICU and hospital, as well as the time between knowing the prognosis and deciding to proceed to "comfort care" treatment. Comfort care emphasizes the quality of the last days of life, rather than their quantity. Meetings with family members should be based on trust and a clear understanding that failing to provide new measures or withdrawing life support does not mean suspending or withdrawing care.6

Regarding symptom control, Aslakson et al.3 cites that opioids are still the main option for pain control in critically ill patients. Intensivists should be prepared to medicate patients before performing procedures such as chest drainage and device removal. Even routine procedures, such as bathing and changing position, can be very painful for some patients.

According to Almeida & Marcon,4 dyspnea is treated by proper care of the underlying disease, such as using diuretics and inotropic agents for heart failure, stopping intravenous hydration and offering non-pharmacological therapy. Opioids are the drug of choice for dyspnea at the end of life, as well as for dyspnea refractory to treatment in other diseases. The use of anxiolytics can be useful to reduce the anxious component of dyspnea. Other medications can be used as adjuvants, such as diuretics, bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Positioning the patient with unilateral lung disease (change to specific decubitus) can be an important non-pharmacological measure. Oxygen is considered for patients with hypoxemia, but some studies have found no benefit from oxygen therapy compared to room air in non-hypoxemic patients.19 Artificial nutrition and hydration do not improve the outcomes of end-of-life patients and can sometimes worsen their discomfort. At this point, artificial nutrition and hydration can cause nausea and increase the risk of aspiration.1 Mendes et al.20 point out that artificial nutrition and hydration are clinical interventions that can be suspended or withdrawn at any time during treatment. Decisions should be based on evidence, good practice, clinical experience and judgment. There must be an effective line of communication with the patient, family members and/or decision-maker, and the patient's autonomy and dignity must be respected.21,22

Through a review of the literature, this study found that the provision of palliative care to seriously ill patients and their families must follow the wishes of the patient themselves, their relatives and the multi-professional team. With regard to the patient's own wishes, the autonomy of the individual and the principle of non-maleficence must be respected, prioritizing decisions by consensus within the maximum certainty of irreversibility. Thus, the team's decision must be preceded by the consent of the patient or their legal representatives, recorded in the medical records.

None.

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2024 Malaquias, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.